THE YEARLY READER

1974: “I’m Just Glad It’s Over”

Hank Aaron’s pursuit of Babe Ruth’s career home run record reaches a storybook conclusion after a burdensome run in which he is deluged with the attention of fans, the media—and racists.

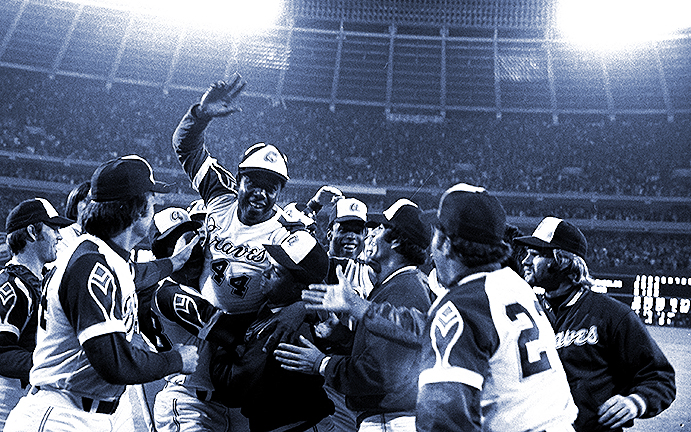

Feeling as much relief as satisfaction, Hank Aaron basks in the glow of his 715th career home run that surpassed Babe Ruth’s all-time career mark. (Associated Press)

For many years, one could look alphabetically through the baseball encyclopedia and not go far to find the player with the most home runs.

He was the first one listed.

For twenty remarkably consistent years, Henry Aaron’s home run numbers were as even-tempered as his personality. He never had the eye-popping year, like Hack Wilson in 1930, Roger Maris in 1961 or Barry Bonds in 2001, years that baseball addicts discuss endlessly into the night. Year in and year out, the durable Aaron could always be counted on to methodically contribute his yearly dose of 30 or 40 homers.

Throughout the 1960s, Willie Mays seemed the odds-on favorite to break Babe Ruth’s seemingly unreachable career home run mark of 714, with Aaron quietly looming as a dark house candidate. But Mays’ game went into sharp decline as he entered his late 30s, while Aaron—barging ahead as if he never turned 30—passed Mays up in early 1972 as he neared 40.

BTW: Mays, who retired in 1973 with 660 home runs, would likely have at least 700 had it not been for two years lost to military service early in his career.

As Aaron gradually narrowed the distance between himself and Ruth with each passing round-tripper, the national spotlight grew ever more intense upon him. Once jealous of the attention Mays got before surpassing him, Aaron now began to feel the side effects of the media focus—and would have gladly given it all back to Mays.

The mail poured in for Aaron to the sum total of a million letters; not all of them wished Aaron encouragement. Many began with the words, “Dear nigger.”

Aaron never felt comfortable playing in the Deep South, where he played minor league ball in the early 1950s and endured the Jackie Robinson litmus test. In 1966, Aaron became one of the least content players to tag along with the Braves when they moved from racially benign Milwaukee to Atlanta—a flashpoint of the civil rights movement, a region dotted with bigots who pined for the days of Jefferson Davis.

The nonstop flow of virulent hate mail, some of which doubled as death threats, was seriously heeded by authorities; Aaron was given a full-time bodyguard, as was his college-aged daughter—who actually met with an attempted kidnapping. Aaron himself told his teammates not to sit near him in the dugout lest they became collateral damage in a sniper attack.

Hoping to break Ruth’s record quick enough so that the spotlights would turn off, Aaron entered 1973 needing 41 homers to tie Ruth, 42 to surpass him.

He hit 40.

Stuck at 713, Aaron would now have to deal with the media frenzy and hate mail for six more unnerving months before he could swing a bat again in 1974.

Clearly, it wasn’t a matter of whether Aaron would break the record, but when. Just two homers shy of surpassing Ruth, many assumed the mark would be broken quickly. Too quickly, Atlanta owner Bill Bartholomay worried, as the Braves began the 1974 season with three games at Cincinnati before opening up their first homestand. Bartholomay wanted Aaron to hit 714 and 715 at home before packed houses, and thus decided that Aaron would sit out the first three games at Cincinnati. Aaron was agreeable to the idea; Bowie Kuhn was not. Baseball’s commissioner, in a move surely without precedent, ordered the Braves to play Aaron in at least two of the three games at Cincinnati.

Bartholomay was bittersweet when Aaron took his first swing of 1974 on the road against the Reds’ Jack Billingham; the ball cleared the left-field wall for 714.

After skipping the second game and going hitless in the third to meet Kuhn’s road quota, Aaron and the Braves came home for their first home game, a Monday night affair against the Los Angeles Dodgers that seemed tailor-made for a major event. A sold out Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium was dressed up with Opening Day bunting and an American flag painted in the shape of the lower 48 states in shallow center field; a sparkling pre-game salute to Aaron preceded the game, televised before a massive nationwide audience. It was as if the evening’s script demanded 715.

Aaron wouldn’t disappoint.

After walking in his first at-bat against Dodgers starter Al Downing, Aaron came back to the plate in the fourth with two outs and no one on. After taking a ball, Aaron’s eyes lit up as the next pitch came in belt-high and over the plate. Using his classic quick-wrist motion, Aaron lofted it high and deep—and over the left field fence, under the desperate reaches of the bleacher fans’ pool nets and into the Braves’ bullpen. The large, ground-based scoreboard behind the bullpen blared “715” as Atlanta reliever Tom House became $10,000 richer by catching and retrieving the ball, as Major League Baseball promised.

BTW: When Aaron scored after the walk on Dusty Baker’s double, he broke another record—the all-time National League mark for career runs…Cognizant of the reward for snaring #715, Dodgers left fielder Bill Buckner began climbing over the outfield fence before realizing he had no chance for it.

The game stopped for 10 minutes as Aaron, utterly dazed and relieved, was hugged by everyone from his teammates to his mother. Speaking to the crowd, Aaron was simply gratified that the pursuit—and the nightmare—was over.

Over it was. Life became relatively normal for baseball’s new home run king, who would spend the rest of the 1974 season hung over from the adrenaline rush that began it and quietly finished out the year with 20 home runs, 69 runs knocked in and a .268 batting average—the latter two stats representing career lows. Afterward Aaron was ceremoniously returned to Milwaukee, where he had begun his big league career in 1953—and where he was now going to finish it as a designated hitter for the Brewers. When he put his bat away for good at the end of 1976, Aaron had raised the bar for the next challenger at 755.

Not a bad way to begin baseball’s encyclopedia.

On the night of 715, the Dodgers’ loss to the Braves was their first of the year. They wouldn’t lose many more in 1974.

After several years of promise, the Dodgers finally evolved into an all-around force that would secure baseball’s best record at 102-60. For once the Dodgers did it with more than just strong pitching, snapping out of a decade-long hitting malaise with a youthful infield that would stick together for the next decade.

Davey Lopes and Bill Russell, both converted from the outfield, respectively formed the middle infield at second base and shortstop. Ron Cey, named the “Penguin” for his waddling strut, anchored third base. But the idol of the bunch was first baseman Steve Garvey, a personable type with Popeye-like forearms who became the first write-in candidate to start the All-Star Game—and proved his presence by being named the game’s Most Valuable Player. Garvey wasn’t done, adding the NL MVP for a solid regular season performance in which he batted .312 with 21 homers and 111 RBIs.

BTW: Cey took over at third base for Garvey, who was a flop at the hot corner with an errant throwing arm; Garvey’s superior glove work made him a better fit at first base.

Dodging Instability

No team has fielded the same infield for eight straight years as the Dodgers did from 1974-81 with Steve Garvey, Davey Lopes, Bill Russell and Ron Cey. Here’s how many different Dodgers regularly started in the eight years before their reign—and the eight years after.

Dodger pitching was all too happy to finally be supported by the offense. The staff had one 20-game winner (Andy Messersmith, at 20-6), nearly another (Don Sutton, at 19-9) and would have had one more in 31-year-old southpaw Tommy John—having a career season—had he not been struck down with a mid-season elbow injury that ended his year. John’s ensuing surgery, in which a tendon from his right arm was transplanted to his left elbow to replace another that snapped, was so revolutionary and successful that the procedure would be named after him.

BTW: John’s recovery would take a year and a half, but it would be worth the wait; he would win 164 games in 14 years after the surgery, pitching to the age of 46.

John’s medical travails were in sharp contrast to reliever Mike Marshall—whose effective durability made him the standout of standouts on the Los Angeles staff. Marshall applied his sworn belief in kinesiology—the study of the mechanics of body movements—and answered the call from the bullpen a major league-record 106 times while throwing 208 innings, the most ever by a full-time reliever; he set another record by appearing in 13 straight games during June. Quality accompanied quantity, as Marshall secured a 15-12 record, 21 saves, a 2.42 earned run average and the NL’s Cy Young Award.

Under Walter Alston, fulfilling his 21st consecutive one-year contract as manager for owner Walter O’Malley, the Dodgers held off the defending NL champion Reds, who had the majors’ second-best record at 98-64—small comfort for a team without a postseason.

Los Angeles had little trouble in the NLCS against the Pittsburgh Pirates, whose impressive stretch run—winning 37 of their final 54 games after sporting a losing record in mid-August—relieved the NL East of a second straight divisional champion barely hanging over the .500 mark. A second major NLCS upset in two years would not be in the cards, however; the league-leading hitting of the Pirates was cracked down by the league-leading pitching of the Dodgers—especially by Don Sutton, who won two starts while allowing just one run in 17 innings to help give the Dodgers a 3-1 series win.

In the American League, it was business as usual for the Oakland A’s. Reggie Jackson and Billy North got into one clubhouse fight. Blue Moon Odom and Rollie Fingers got into another. And those were only the scuffles that got reported. Catfish Hunter, having an outstanding year in which he would lead the AL in both wins (25) and ERA (2.49), squared off less physically (but no less intensely) against Charles Finley after the A’s owner refused to defer half of Hunter’s salary into an annuity—even though Hunter’s contract called for it. An arbitrator ruled in Hunter’s favor after the season, voiding the contract and making him baseball’s first millionaire free agent.

BTW: The hapless Ray Fosse—run over by Pete Rose in the 1970 All-Star Game—hurt his back trying to break up the fight and missed half the season.

Despite the never-ending internal strife, the A’s kept winning, taking their fourth straight AL West title and, after a well-pitched ALCS over the Baltimore Orioles, their third straight AL pennant. Now managed by Alvin Dark—taking over for an exasperated Dick Williams—the A’s were hardly at their best, especially mired in a season-long hitting funk for which their batting average placed 11th out of 12 AL teams. But the pitching, led by workhorses Hunter, Ken Holtzman (19-17, 3.07 ERA) and Vida Blue (17-15, 3.26 ERA), topped the majors in team ERA at 2.95 and helped separate Oakland from middling AL West competition, led by the Texas Rangers—nomadic manager Billy Martin’s latest reclamation project.

BTW: Stagnant at 63-65 by the end of August, the Orioles won 28 of their last 34 to win the AL East.

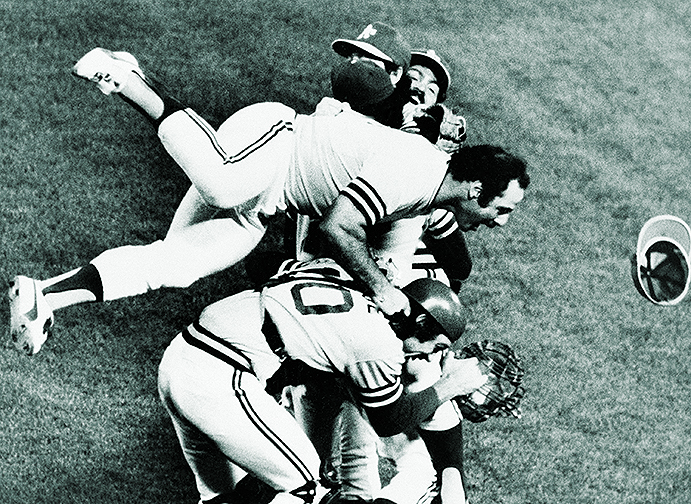

Ecstatic Oakland A’s players celebrate after winning the 1974 World Series over the Los Angeles Dodgers. It was one of the few times during the year that Oakland players jumped on one another…for joy. (Associated Press)

Named the “California Series” for the unprecedented face-off of two West Coast teams, the World Series was yet another example of the Oakland A’s getting things done their way: Strong pitching, weak hitting, great defense, tight outcomes and, ultimately, victory. Three of their four victories over Los Angeles were decided by scores of 3-2; the Dodgers’ only win of the Series, in Game Two, was also 3-2.

The key to the Series was the defensive play of both teams. The Dodgers made one mental mistake after another, with the A’s almost always taking full advantage. Oakland, on the other hand, performed continuous glove magic—particularly from veteran second baseman Dick Green, whose 0-for-13 performance at the plate was excused with acrobatic, game-saving defensive plays throughout the entire Series.

BTW: True to form, Dodgers reliever Mike Marshall appeared in all five games of the World Series, allowing just a run on six hits in nine innings while striking out 10.

Tin Dynasty

The Oakland A’s managed to win six straight postseason series from 1972-74 with offensive numbers even deadball era teams would have been ashamed of, as shown below. Yet they nevertheless prevailed with a combination of clutch hitting, stifling pitching and sensational defense.

The A’s 4-1 Series win made them the first team outside of the New York Yankees to win three straight championships. Charles Finley, who a decade earlier looked hopelessly lost just trying to reach .500, had become the unlikely lord of the game’s latest dynasty.

Finley’s A’s would remain strong, but the peak had been reached. Losing Catfish Hunter in 1975 would hurt them. Losing Reggie Jackson in 1976 would hurt them more.

By 1977, the advent of free agency would destroy them.

Forward to 1975: Birth of Renaissance America’s passion for baseball is re-awakened with, arguably, the greatest World Series ever between Boston and Cincinnati.

Forward to 1975: Birth of Renaissance America’s passion for baseball is re-awakened with, arguably, the greatest World Series ever between Boston and Cincinnati.

Back to 1973: Take My Division, Please Six mediocre teams stumble and bumble with one another in a memorable National League East race.

Back to 1973: Take My Division, Please Six mediocre teams stumble and bumble with one another in a memorable National League East race.

1974 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1974 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

1974 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1974 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

The 1970s: Power to the Player Curt Flood’s sacrificial stand to win free agency opens the door for the biggest challenge yet to the reserve clause, which is eventually shattered—but not without fans suffering from numerous player strikes and holdouts.

The 1970s: Power to the Player Curt Flood’s sacrificial stand to win free agency opens the door for the biggest challenge yet to the reserve clause, which is eventually shattered—but not without fans suffering from numerous player strikes and holdouts.