THE YEARLY READER

1980: Finally Philly

After years of developing into a consistent winner, the Philadelphia Phillies attempt to win their first-ever World Series against the Kansas City Royals, who feature George Brett—mounting a serious challenge to hit .400 for the year.

The Philadelphia Phillies and the Kansas City Royals had plenty of recent frustration in common when they met in the 1980 World Series.

Both teams had lost league championship series in three straight years, from 1976-78. Both suffered a disappointing drop-off in 1979. Both started anew under first-time managers in 1980. And by meeting up in the Fall Classic, they represented for the first time in 60 years two teams in search of their first-ever championship.

But that’s where the similarities came to a stark end.

One team was among the oldest of baseball franchises, a traditional flop on the fringe of centenarian status. The other was barely a pre-teen that avoided the pain of expansion infancy and took the fast track to success.

If entitlement favored seniority, then justice would finally be delivered for the Phillies.

Born in 1883, the Phillies definitively set the tone for the next 60 years by finishing 17-81. They would be the most consistently awful franchise in baseball, struggling under a string of incompetent owners while performing in a ballpark (Baker Bowl) whose decrepit structure offered an occupational hazard for the few who showed up.

The Phillies were rescued from futility in 1943 by new owner Robert Carpenter, whose family had wealthy business ties to the DuPont Corporation. Under the Carpenters—first Robert, then Robert Jr., then grandson Ruly in 1972—the cellar dwelling was over, replaced by a stubborn middle occupancy within the National League that created a new level of frustration. The improved results fell short of those anticipated by Phillies fans, who harbored all the sympathy of a pack of vultures.

The fans’ expectations—and ensuing anger—only intensified through the 1970s, as the Phillies failed to win it all despite a powerful roster that included sluggers Mike Schmidt and Greg Luzinski; defensive stalwarts in shortstop Larry Bowa, center fielder Garry Maddox and catcher Bob Boone; and ace pitcher Steve Carlton. The free agent addition of Pete Rose in 1979—tagging the Phillies with the NL’s highest payroll—got them no closer. The vicious boo birds at Veterans Stadium couldn’t let go of the franchise’s historical inabilities. No World Series titles. No NLCS triumphs. A 6.5-game lead blown in the final two weeks of 1964.

Dallas Green, the Phillies’ new manager in 1980, felt he had the cure for the team’s recent bout of underachieving. Sensing that his collection of high-priced All-Stars had developed too individual a mindset, Green hammered a “We, not I” campaign that worked only in annoying, not galvanizing, his veteran players. Not even the combative Green’s intimidating presence—a big, burly frame, a booming voice and a rigid jaw structure that made him look more suited as an NFL linebacker coach—could scare the players his way.

BTW: Green replaced Danny Ozark, who managed the Phillies to NL East titles from 1976-78—some say, in spite of his clueless managerial instincts.

Green himself was part of the problem, making a bad habit of criticizing his players to the press—and thus violating some of the very rules he had laid out. But as the 1980 season advanced with the Phillies barely skating above .500, the players found themselves fighting battles on many fronts: Against Green, the hostile fans, the press and sometimes themselves. It was a clubhouse more chaotic than that of George Steinbrenner’s New York Yankees, if that was possible.

BTW: In midseason, the local press uncovered a story in which Philadelphia players—and their wives—were taking speed through the Phillies’ minor league physician in Reading. Few denied the story and some later confirmed it.

When the Phillies were swept at Pittsburgh in mid-August—dropping them six games behind the defending champion Pirates—Green’s protruding jaws went overtime, excoriating his players in a close-door meeting easily heard outside by waiting reporters.

Slowly at first, the Phillies soon turned it on for the home stretch, going 36-19 in the wake of Green’s rant. Equally helpful was a season-ending injury to Willie Stargell, the Pirates’ 1979 hero; the Bucs were 16-29 after his departure and quickly exited the NL East race.

One Phillie who certainly heeded Green’s anger was Mike Schmidt. The star third baseman, suffering his own love-hate relationship with Philadelphia fans, shredded apart a long-standing label as a choke artist in the clutch. He hit .338 with 21 home runs and 48 RBIs over the last 55 games, had numerous game-winning hits, and smacked an extra-inning home run to clinch the NL East at Montreal—who had been running neck-to-neck with the Phillies through most of September. Schmidt’s heroics won him the NL’s Most Valuable Player award for the first—but not last—time.

BTW: Schmidt on the local fans and press: “Philadelphia is the only city where you experience the thrill of victory one day and the agony of reading about it the next day.”

The Phillies were also buoyed in the end by Carlton, who at 35 won his third—but not last—Cy Young Award with a 24-9 record, a 2.34 earned run average and 286 strikeouts in 304 innings; and by Rose and reliever Tug McGraw, two of the game’s cockiest players, whose postseason experiences and attitudes may have helped gel an otherwise lost clubhouse.

BTW: McGraw allowed just one earned run in 39.1 innings of work after Green’s chewing out in Pittsburgh.

Trying to chuck the NLCS monkey off their backs, the Phillies’ fourth attempt in five years to get to the World Series meant defeating the NL West champion Houston Astros. If they thought the NL East race had been an exhaustive exercise, they had no idea what was in store for them in the NLCS with the tough-as-nails Astros, making their first-ever postseason appearance—and barely, having blown a three-game lead in the season’s final weekend at Los Angeles. It took a one-game playoff to overcome the Dodgers and win the West.

The Phillies took the NLCS opener at home, 3-1, a tight result that would prove to be the yawner of the series. The next four games would take the best-of-five series to the limit and beyond, all extra-inning affairs with an abundance of roller-coaster lead changes, blown calls, reversed calls and un-reversed calls that nearly rendered the World Series anticlimactic.

Down in the series 2-1 with the final two games to be played in the hostile, raucous atmosphere of the Houston Astrodome, the Phillies somehow managed to advance. An especially wild Game Five decider saw the Phillies score five in the eighth off Nolan Ryan to erase a three-run Astros lead; losing that lead when Houston notched two in the bottom of the inning; and then taking it back for good in the 10th when Garry Maddox doubled home the pennant-winning run in an 8-7 victory.

Most observers were convinced the Phillies, emotionally and physically spent, would have nothing left against a superior World Series opponent in the Kansas City Royals.

Begun in 1969 by pharma magnate Ewing Kauffman, the Royals eschewed big-name, over-the-hill talent as other expansion franchises instinctively sought, and instead entrusted their future to players without names but with promise, backed by an aggressively built farm system. Many of those early prospects had, by 1980, become the stars of the team, with the star of stars—a blue-eyed, blond-haired West Virginian native named George Brett—ready to absolutely explode with one of the most spectacular campaigns in modern times.

Brett’s 1980 season started nominally enough, batting under .300 by Memorial Day. Then he turned it up—way up—well beyond the Alps of envy usually reserved for legends like Ted Williams.

Over the next three months, Brett would bat an astounding .481—103 hits in 214 at-bats—and on August 26 led the world many times over with a .407 batting average. Some hitters see the ball as a softball when they’re hot; Brett saw it as a juiced-up beach ball. He was in such a groove, when he pulled together a few consecutive games with a single hit in each, he sighed, “I’ve got to get out of this slump.”

Brett stayed at or above the .400 mark until September 19, when the combination of pressure, the national media and injuries finally took its toll, succumbing to a month-long ankle injury in June and a bruised hand that cost him 10 more days in September. Over the final two weeks, he hit .304—superb by common player standards, but for Brett a sharp drop from immortality, slipping below the .400 mark and leaving Williams, then as now, as the last player to finish above the magic barrier.

Despite missing 45 games on the year, Brett still managed to muster up terrific numbers alongside his season-ending .390 batting average with 24 home runs and 118 RBIs to give him, easily, American League MVP honors.

As Brett went, so went the Royals. Under first-year manager Jim Frey, Kansas City quickly bolted away from a weak AL West once Brett got white-hot, coasting to a 14-game cushion by season’s end. Brett was buffeted by leadoff man Willie Wilson, who led the league in hits (230) and runs (133); by starting pitchers Dennis Leonard (20-11, 3.79 ERA) and Larry Gura (18-10, 2.96); and by second-year closer Dan Quisenberry (12-7, 3.09, 33 saves).

BTW: Frey replaced Whitey Herzog, who brought the Royals their first three divisional titles but also wore out his welcome with both Kauffman and the players.

In Sync With the Heat

George Brett’s chilly start, sizzling summer stretch and late cooling off in 1980 could have easily been adopted by the National Weather Service to substitute Kansas City conditions.

Kauffman proclaimed in 1973 that sparkling new Royals Stadium would help give the Royals five pennants in 10 years. He might have been right had it not been for the New York Yankees, who got in the way of three of those five from 1976-78—and now would attempt to deny a fourth as the teams hooked up yet again in the ALCS.

Though the Yankees had forged an impressive comeback after a rough 1979 campaign with a 103-59 mark—barely outdistancing AL champion Baltimore, at 100-62—the Royals liked their chances this time around, having taken eight of 12 games over the Yankees during the regular season.

Royal confidence was well justified. Kansas City hitters hit and the pitchers kept Yankees bats in check as the Royals impressively swept in three, capping the triumph when Brett launched a pennant-clinching home run into Yankee Stadium’s upper deck. Embarrassed at the three-and-outing, George Steinbrenner had his predicted tantrum, firing the man he made as scapegoat—third-base coach Mike Ferraro. In utter disbelief, manager Dick Howser said he’d go if Ferraro went; Steinbrenner obliged.

BTW: Brett, who hammered the Yankees with a .425 average and 22 RBIs in 10 regular season games, was “only” 3-for-11 in the ALCS—but two of his hits were home runs.

Rested with the sweep, the Royals discovered through the first two games of the World Series that the Phillies were not out of gas—but rather on a spirited high carried over from the NLCS wars. Nail biting remained routine at the Vet as the Phillies overcome 4-0 and 4-2 leads in Games One and Two, respectively, to win by scores of 7-6 and 6-4. If being down two games in the series was bad enough for Kansas City, they had a bigger problem.

George Brett was fighting a new injury: A case of hemorrhoids.

Frantically, the Royals and Brett did everything they could to get him fixed. A small surgery and a full day of bed rest later, and Brett was ready for Game Three at Kansas City by declaring with humor, “The pain is behind me.”

Brett thanked the doctor by homering and doubling in another tight contest, won 4-3 by the Royals in 10 innings, and added a run-scoring triple in a 5-3 Game Four victory. But Kansas City lost the all-important fifth game as Mike Schmidt—Brett’s opposite number as MVP third baseman—took over the spotlight. Schmidt homered to give Philadelphia an early 2-0 lead, then singled to start a winning two-run rally in the ninth after the Phillies had fallen behind. Philadelphia headed back home with two shots to take the victor’s crown at last.

BTW: Schmidt’s base hit deflected off of Brett’s glove; Brett was playing closer in as Schmidt had bunted for a hit off him a day earlier.

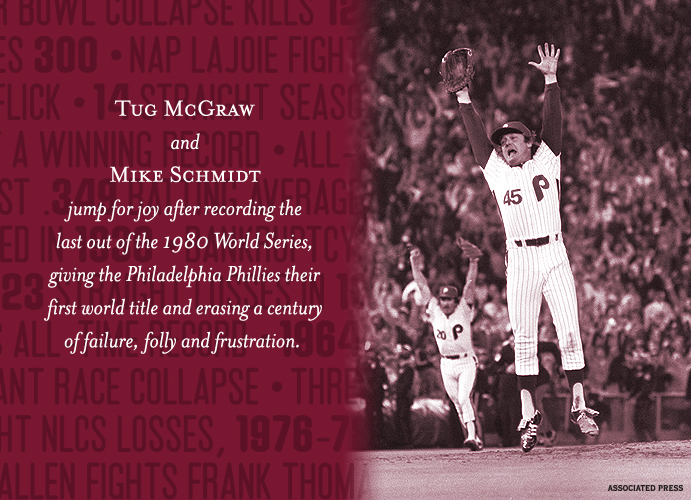

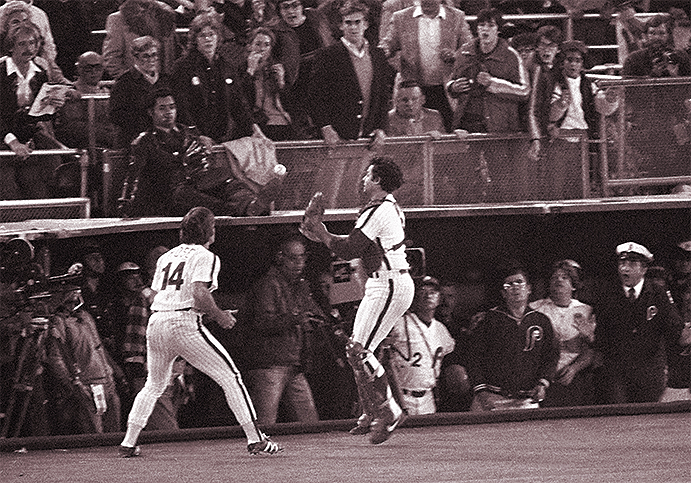

Phillies fans and players are held in brief suspense when a pop fly squirts out of catcher Bob Boone’s glove—but Pete Rose is there to catch the carom, keeping a bases-loaded Kansas City rally from spinning out of control. The Phillies would secure the World Series trophy one out later. (Associated Press)

Hardened as ever from a century of luckless baseball, the long-suffering Phillie fans wouldn’t believe a world championship until the final out was snared. Even as the Phillies were coasting 4-0 behind Carlton in the seventh inning of Game Six, the 66,000 that jammed the Vet couldn’t help but think bad thoughts. That the Phillies had trailed at some point in each of the first 10 postseason games only made them more edgy. And it appeared the ghosts of Phillie collapses past were ready to bust out when, with one out in the Royals ninth, the bases loaded and the go-ahead run at the plate in Frank White—a foul pop-up squirted out of the mitt of Bob Boone.

To the rescue came Pete Rose, in perfectly fortuitous position to glove the bobble and secure the second out.

Then Tug McGraw struck out Willie Wilson for the final out, and the City of Brotherly Love was turned upside down and all around with massive pandemonium.

When the city closed down the next day to revel in triumph with a million-plus Philadelphians lining the victory parade, all that embattled Phillies manager Dallas Green could do was sigh in relief, “I don’t want to put up with another year like this one.”

After 97 long years, the Phillies finally got to taste the top. The Royals would have to wait their turn, though it would come soon enough given their outstanding track record to date. Phillies fans, hardened over a century of failure, were instinctively more skeptical of future gains even in the afterglow of victory.

If the Phillies were to indeed reach the top again, they wouldn’t do it under Ruly Carpenter. Even as he celebrated the here and now, he rued the future. Carpenter saw a system going haywire under spiraling free agency and owners who had no sensible plan to deal with it. So five months after taking the victory ride down Broad Street, Carpenter announced he was selling.

The 1980 season had made Carpenter a champion; 1981 would make him a prophet.

Forward to 1981: No Ball, One Strike A criplling midseason player strike plays havoc with the schedule and the integrity of playoff eligibility.

Forward to 1981: No Ball, One Strike A criplling midseason player strike plays havoc with the schedule and the integrity of playoff eligibility.

Back to 1979: One for Pops and His Family After years of injury and career decline, Willie Stargell comes alive at 39 to lift the Pittsburgh Pirates.

Back to 1979: One for Pops and His Family After years of injury and career decline, Willie Stargell comes alive at 39 to lift the Pittsburgh Pirates.

1980 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1980 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

1980 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1980 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

The 1980s: Corporate Makeover Baseball enjoys a healthy boom on several fronts, with increased attendance, corporate sponsorship and memorabilia sales; players also continue to enjoy skyrocketing salaries, but some abuse their newfound riches by delving into illegal drugs.

The 1980s: Corporate Makeover Baseball enjoys a healthy boom on several fronts, with increased attendance, corporate sponsorship and memorabilia sales; players also continue to enjoy skyrocketing salaries, but some abuse their newfound riches by delving into illegal drugs.

The 220-game winner looks back at his early days with the Cardinals and Astros, his peak years with the Dodgers, and an endearing hobby photographing old ballparks.

The 220-game winner looks back at his early days with the Cardinals and Astros, his peak years with the Dodgers, and an endearing hobby photographing old ballparks.