THE YEARLY READER

1983: The Good, the Old and the Ugly

The Baltimore Orioles wind their way through a postseason taking on challengers in a Chicago White Sox squad priding itself on “winning ugly” and the Philadelphia Phillies, baseball’s surprising over-the-hill gang.

It can be a dangerous thing for a new manager to inherit a winner. To replace a legendary manager at the same time begs a risk for vocational suicide. With every John McGraw, Joe McCarthy and Sparky Anderson that stepped down, there was a Bill Terry, Steve O’Neill and John McNamara asked to take over with everything to lose and nothing to gain—except to uphold the excellence.

In 1983, Joe Altobelli would become the benefactor of Earl Weaver’s legacy. The new skipper of the Baltimore Orioles could have easily felt he was being set up for a fall. Altobelli was inheriting a team that, yes, did field one superstar with perhaps another on the rise. But he was also handed a roster with an aging outfield, an aging designated hitter, an aging bench, and a veteran pitching rotation showing signs of collapse. Above all of this, of course, was the pressure of living up to the legend of the pugnaciously brilliant Weaver, who averaged 96 wins in his 14 seasons at Baltimore with six divisional titles and four American League pennants.

Managing to outlast a highly competitive AL East, Altobelli’s Orioles met with two of the more unlikely postseason participants in baseball annals. One was a rough and tough pack of overachievers who thrived on the catcalls of critics who claimed they won ugly. The other was a collection of elderly All-Stars that might have easily been confused for an Old Timers’ Day squad, yet with enough poise and sage to retain a knack for winning.

When it was all over, Joe Altobelli would become Weaver’s equal in one important aspect, matching at one the number of Oriole World Series titles won under his command.

Of the many names that came up in the hunt for Weaver’s successor, Altobelli’s merited little more than darkhorse consideration. He’d won the National League’s Manager of the Year award in 1978 piloting the San Francisco Giants, but that was sandwiched between two worthless years, the latter of which got him fired in 1979. Altobelli was passing the time as the New York Yankees’ third base coach when the Orioles called him in.

BTW: Cal Ripken Jr. lobbied for his father, Cal Ripken Sr., to be the new Baltimore skipper—and had the 22-year old held the clout he would consolidate in later years, he might have gotten his wish.

The one sure thing in Altobelli’s lineup was slugging first baseman Eddie Murray, well into his prime at age 27. But across the infield at shortstop was a rising star emerging as something beyond sure: Cal Ripken Jr. Now in his second full season at Baltimore, the 22-year-old Ripken was out there every game, every inning—as he would be for eons to come—playing great defense and improving his already sound batting skills with each passing month.

After a sharp start muted by a seven-game losing streak in late May, the Orioles won 32 of their next 40 to pull away with the AL East lead towards a playoff spot. Ripken cranked it up for the stretch run, hitting nearly .400 in September to finish his sophomore year batting .318 with 27 home runs and 102 runs batted in. Add on AL highs with runs (121), hits (211), doubles (47)—and of course, games played (162)—and Ripken copped the AL Most Valuable Player award—edging out Murray, who hit .306 with 33 homers and 111 RBIs.

Not as newsworthy yet as crucial to the Orioles’ success were the efforts of two young starting pitchers with infant major league experience. Mike Boddicker (a 16-8 record and 2.77 earned run average) and Storm Davis (13-7, 3.59) aided workhorse Scott McGregor (18-7, 3.18) to offset injuries to former Cy Young winners Jim Palmer and Mike Flanagan—and a dreadful turnabout from Dennis Martinez, which he would later blame on alcoholism.

Through the end of July, it looked as though whoever won the AL East could phone it in at the ALCS against a much inferior AL West champion. But out of the West’s morass of mediocrity came a sudden burst of fire from an improbable source: The Chicago White Sox.

A year before they were famously tagged for “winning ugly,” the White Sox were just plain ugly, at least emotionally. No one seemed happy. Players complained of platooning, of each other, of deep fly balls dying in the expansive Comiskey Park outfield. Fired coaches mouthed off to the media. Tony La Russa, the majors’ youngest manager at 37, nearly came to blows with White Sox announcer Jimmy Piersall. Sporting a deadly serious scowl that perfectly mirrored the times, La Russa was vociferously booed by Chicago fans—even as he was in the process of giving them the club’s first back-to-back winning campaigns since the mid-1960s.

The booing continued well into 1983, as the White Sox scraped the .500 mark as a number of other AL West teams struggled to become postseason-worthy. Suddenly and like a rocket, Chicago bolted from the pack in July to take sole command. None of the other contenders sweated, believing the White Sox would promptly fall back down to Earth. Texas Rangers manager Doug Rader summed up that attitude when he told the press on the eve of the Sox’ visit to Arlington in mid-August: “(The White Sox’) bubble has got to burst. They’re not playing that well. They’re winning ugly.”

It was the first mention of anything “ugly” related to the performance of the White Sox, who along with their fans soon took the backhanded compliment to heart. Chicago won three of four from Rader’s Rangers and continued their maddening rush, one in which they would win 50 of their final 66 games to finish a remarkable 99-63.

BTW: No one else could reach .500 in the AL West; second-place Kansas City, at 79-83, finished a full 20 games back of Chicago.

Pitching Beauty Amid the Ugliness

Like much of the White Sox, the team’s three top pitchers—LaMarr Hoyt, Rich Dotson and Floyd Bannister—struggled through the all-star break. But the three caught fire in the season’s second half and undoubtedly deserved primary credit for the Sox’ AL West triumph.

Sparking the White Sox was a trio of pitchers all having the best years of their careers—and, in the season’s second half, perhaps the best of any career. Gruff-looking Cy Young Award winner LaMarr Hoyt (24-10, 3.66 ERA), 24-year-old Rich Dotson (22-7, 3.23) and fireballer Floyd Bannister (16-10, 3.35) combined for an incredible 40-3 record down the stretch to fuel the White Sox’ drive. Complementing the pitchers were a couple of muscle-bound sluggers who happily approved of the brought-in Comiskey outfield fences: Rookie Ron Kittle, knocking out 35 home runs a year after belting 50 in the Pacific Coast League; and veteran Greg Luzinski, whose slow feet and sloppy defense made him thrilled to be an American Leaguer, as the designated hitter slammed 32 over the fence.

BTW: It was Luzinski’s third year at Chicago after being ridiculed for his glove in the National League at Philadelphia.

The White Sox beautifully played the role of ugly lucklings to start the ALCS at Baltimore. In a 2-1 triumph, Chicago’s winning run scored on a double play after reaching base on an Orioles error. But the Sox ran out of luck—and more importantly, offense—over the next three games, scoring a total of one run against the Orioles’ young and unyielding pitching.

Having dispensed of the ugly, the Orioles now readied to do battle with the old at the World Series.

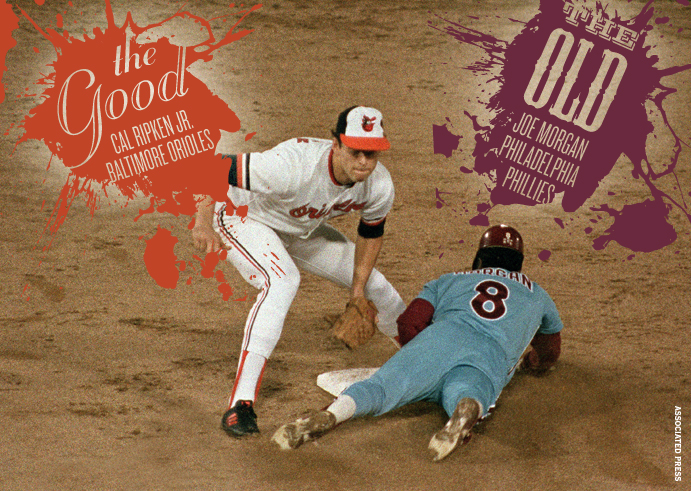

The Philadelphia Phillies entered 1983 as perhaps the best team of 1973. With seven players very near, at or above the age of 40—and an everyday lineup that included just one player under 30—the Phillies were relying on an aging base of accustomed All-Stars whose experience dictated a strong determination to win. The names of the elders were hardly lost on baseball fans: Pete Rose, Joe Morgan, Steve Carlton, Tony Perez and Tug McGraw. For many of these players, it was their last stop before Cooperstown—and the Phillies, who had dealt away some hot young prospects to acquire them, announced to the baseball world that the future wasn’t simply now, it was yesteryear.

BTW: Among those raised by the Phillies and grown into stars elsewhere were Ryne Sandberg, Julio Franco and Mark Davis.

Although the Phillies’ 43-42 record on July 17 was good enough to share first place in the NL East, it wasn’t good enough for the players or general manager Paul Owens—who fired manager Pat Corrales and placed himself into the dugout as field general. Nicknamed the Pope because of his likeness to said pontiff, Owens continued to watch his collection of veterans sputter and slump throughout the summer, yet remained in playoff contention with no one else pulling away from the rest of the division.

BTW: Owens was actually a sort of managerial figurehead; coach Bobby Wine did most of the pitch-to-pitch strategies.

The door left open, the Phillies woke up in September and won 25 of their last 32 games, including 11 straight at one point—all a likely by-product of the veterans’ habit to bring it on home in the clutch. No one embodied the spirit more than Joe Morgan. Struggling just to keep his batting average above .200 for much of the year, the second baseman celebrated his 40th birthday on September 19 by banging out four hits, including two home runs, in a 7-6 win against the Chicago Cubs. The next day he collected four more hits. The hair of opposing pitchers both young and old were more likely to turn gray than Morgan’s as he hit .455 after turning 40 to help lift the Phillies through the final two weeks and into the playoffs.

At the plate, Mike Schmidt remained the Phillies’ primary threat. Though batting an underwhelming .255, Schmidt was pardoned thanks to a NL-high 40 homers and 128 walks—emblematic of a team that finished ninth in league batting but third in on-base percentage and runs scored. In terms of keeping runs off the board, the Phillies were led on the mound by John Denny, a 10-year veteran recently converted to religion and reconverted to winning with a terrific 19-6 record and 2.37 ERA; and by 38-year-old Steve Carlton, whose 15-16 record was misleading when his 3.11 ERA was taken into account.

For the NLCS, the Phillies looked on paper to be huge underdogs to the NL West-winning Los Angeles Dodgers, who not only listed better numbers with a not-so-over-the-hill roster, but had won 11 of 12 games over Philadelphia during the regular season. Yet the Dodgers had won all those games before the Phillies embarked on their successful third act to the season; they were without top closer Steve Howe—serving the first of an eventual seven “lifetime” suspensions for drug use; and their more prosperous hitting talents, such as Pedro Guerrero, Steve Sax and Mike Marshall, lacked the kind of postseason experience that Philadelphia’s “Wheeze Kids” were brimming with. That last intangible made all the difference. Led by Steve Carlton—who won the first and final games of the NLCS—the Phillies ousted the Dodgers, three games to one.

BTW: Overall, the Phillies’ pitching staff allowed just four earned runs in four NLCS contests.

Maybe They Were Just Playing Dead

In coughing up a 1-11 regular season record against the Dodgers, the Phillies mustered a total of just 15 runs—an all-time team low against another opponent during a season series of 12 or more games. For the NLCS, the Phillies showed a different, more potent side of their offense.

The Phillies introduced themselves to the Baltimore Orioles at the World Series much the same way the Chicago White Sox had in the ALCS, with a 2-1 win at Memorial Stadium. But the Orioles again rebounded and took charge after the opening loss, winning three straight to back the Phillies to the brink of Series defeat.

Entering Game Five, the Series had been a story of slumping star sluggers: Mike Schmidt for the Phillies, Eddie Murray for the Orioles. Whoever broke out, it was thought, might make the difference in the Series. This was historical cold comfort for the Orioles; in their last trip to the Fall Classic—in 1979 against Pittsburgh—the Orioles led by the same count and proceeded to lose three straight and the Series.

Murray, batting a wretched .054 with not one RBI over his last eight World Series games, would awake to make the difference in Game Five—homering in his first two at-bats to ignite the Orioles to a 5-0 clincher at Philadelphia. Schmidt, enduring another 0-for-4 effort, finished with just one single, no walks and no RBIs in 20 Series at-bats. As usual, the Veterans Stadium unfaithful let him know about it.

As it was during the ALCS, Baltimore pitching was the true hero of the World Series. Mike Boddicker and Storm Davis, the two Oriole young’ens, won each of their starts, and Jim Palmer chipped in with a victorious Game Three decision in rare relief. Overall, the Orioles limited the Phillies to a .195 average and nine total runs in five games, and capped the postseason with an astonishing 1.10 ERA.

Joe Altobelli’s first year at Baltimore would be his foremost. He would reap one year’s worth of benefits from the Earl Weaver regime and win it all before the organization suffered into a prolonged decline. When Altobelli was fired in 1985, not even the man who replaced him—Earl Weaver—could save it.

But at the very least, Joe Altobelli was able to taste wine before it became water again.

Forward to 1984: The Roar of a Powerhouse The Detroit Tigers bolt out to a 35-5 record and coast from their to their first World Series title since 1968.

Forward to 1984: The Roar of a Powerhouse The Detroit Tigers bolt out to a 35-5 record and coast from their to their first World Series title since 1968.

Back to 1982: Streaking Engagement There’s hardly a dull moment in a year where baseball’s playoff contenders careen about like out-of-control rollercoasters.

Back to 1982: Streaking Engagement There’s hardly a dull moment in a year where baseball’s playoff contenders careen about like out-of-control rollercoasters.

1983 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1983 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

1983 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1983 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

The 1980s: Corporate Makeover Baseball enjoys a healthy boom on several fronts, with increased attendance, corporate sponsorship and memorabilia sales; players also continue to enjoy skyrocketing salaries, but some abuse their newfound riches by delving into illegal drugs.

The 1980s: Corporate Makeover Baseball enjoys a healthy boom on several fronts, with increased attendance, corporate sponsorship and memorabilia sales; players also continue to enjoy skyrocketing salaries, but some abuse their newfound riches by delving into illegal drugs.