THE YEARLY READER

1984: The Roar of a Powerhouse

Led by former Cincinnati manager Sparky Anderson, the Detroit Tigers take first place on Opening Day and never look back, winning 35 of their first 40 games to breeze all the way to a convincing World Series title.

When Sparky Anderson took over as manager of the Detroit Tigers in 1979, he initiated a five-year plan, the ultimate goal of which was to bring a world championship to the Motor City.

Give the man credit for delivering on a deadline.

Triumphant on schedule, the 1984 Tigers—a well-balanced blend of ballplayers who mostly grew together through Anderson’s time-lined program—were more than just another World Series champ. They were immensely dominant from start to finish, never once looking up in the regular season standings, never once trailing in a postseason series. Only one other team in baseball history could make such a claim: The 1927 New York Yankees.

Anderson’s rise in Detroit began from an inexplicable fall from grace at Cincinnati, where spoiled Reds management gave him the boot for two straight second-place finishes after years of star-studded, championship-caliber results. With the Tigers, a team easily capable of playing .500 baseball, Anderson didn’t necessarily inherit a squad in need of serious rehabilitation. More aggressive fortune tellers of the game might have felt five years were more than enough to give the Tigers roster a chance, but Anderson—who at 50 had long since grayed but was now wrinkling to boot—sold his young and talented Detroit players with a patient and comforting old man sage.

The first three years of Anderson’s best laid plans resulted in winning records, but without a serious challenge for postseason entry. The fourth year brought the Tigers within six games of first place with 92 wins, suggesting that they were ramping up.

For year #5, the Tigers exploded out of the gate like no team, before or since.

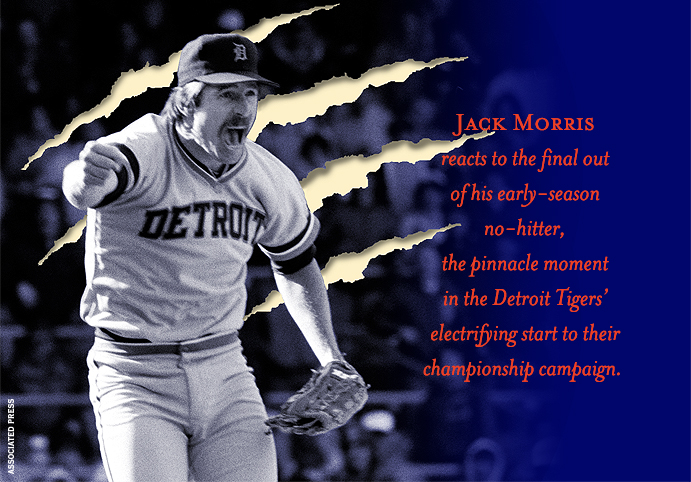

The Tigers won their first nine games. After losing two, they won seven more in a row. That was quickly followed by two more streaks of seven and nine wins each. In all, Detroit won 35 of its first 40 games and tied a major league record by winning its first 17 games on the road—though any home field advantage for opponents had been chipped away by Tigers fans, old and new alike, who came out of the woodwork to support their team. About the only thing that went wrong for the Tigers during this phenomenal first-quarter stretch was a collision on an attempted embrace between ace pitcher Jack Morris and catcher Lance Parrish after Morris tossed a no-hitter against the Chicago White Sox.

BTW: When the Tigers won their 17th straight road game against the California Angels at Anaheim, a sellout throng gave them a standing ovation.

Tigers Untamed

It goes without saying that any team winning 35 of 40 games would have the statistics balanced heavily in its favor. So here’s what the Tigers racked up while accomplishing that record to start 1984.

The Tigers were hardly ego-driven, a blue-collar collection of stars without superstars—a consistent and sound group with no weaknesses to be found anywhere. Among the maturing were the inseparable middle infield duo of Alan Trammell and Lou Whitaker, in the midst of an impressive 18-year run at Detroit starting alongside one another. Parrish, a former bodyguard for Tina Turner, led the Tigers with 33 homers and was tough as nails behind the plate.

Yet the most omnipotent danger for opposing pitchers was outfielder Kirk Gibson, a former football star at nearby Michigan State who the Tigers were lucky to snare in the 1978 draft, while others ahead in line assumed he would favor the NFL. With a gridiron-like mentality, Gibson became a clubhouse leader by embracing challenge and condemning complacency—and took his intensity to the plate, batting .282 with 92 runs scored, 91 knocked in, 29 stolen bases and double-figures in all extra-base categories (including 27 home runs).

BTW: Gibson became the first Tiger to hit 20 home runs and steal 20 bases in the same season.

The unquestioned ace of the Detroit staff was Morris, a 29-year-old right-hander who grated his teammates with a preponderance to pout when things didn’t go right. As with the rest of the Tigers, few things went wrong for Morris in 1984, leading the club with 19 wins against 11 losses.

The man who put the Tigers over the top in 1984 was to be found in the bullpen. In seven previous years toiling in the National League, Willie Hernandez had always been a long reliever, never a closer—a southpaw pitching well enough to keep his earned run average just above 3.00. He had recently developed a screwball to go with a bread-and-butter fastball, and once in Detroit under the tutelage of Tigers pitching coach (and future San Francisco manager) Roger Craig, Hernandez mixed the two pitches perfectly throughout 1984. The Puerto Rico native could do little wrong, recording 32 straight saves before finally blowing one in a meaningless late-season contest, and authored a 1.92 ERA to earn both the American League Most Valuable Player and Cy Young awards.

Standing head, shoulders, waist and knees above the rest of baseball with their white-hot start, the Tigers early and rightfully had October on their minds—which led to a problem for Sparky Anderson: How to keep the momentum on track through the bulk of the regular season. It wouldn’t be easy.

The national media, having made the Tigers their darlings, put the players in high demand of interviews and promotions that threatened to take the team off its focus. Other AL teams began treating the Tigers as world champs long before they could claim it, turning it up a notch whenever they went out to face them. Starting pitching fell flat in midsummer, and a volatile Jack Morris upset the clubhouse air with a series of outbursts and a self-imposed moratorium with the media.

Through it all, the Tigers slipped but never fell. Their worst month of the year came with a 16-15 August. Their 104 total wins—53 at home, 51 on the road—represented a club record and crowned Sparky Anderson as the first manager to win 100 games for teams in both leagues. The Toronto Blue Jays, finishing 15 games behind Detroit for second place in the AL East, never got any closer than 7.5 games after the Tigers’ 35-5 start, and blew their one long shot to actually make a race of it when they lost five of six to the Tigers to start September.

BTW: Though the 104 wins represents a club record, the Tigers did have better years by win percentage in 1909, 1915 and 1934.

The AL West-winning Kansas City Royals were so inferior to Detroit—at 84-78, they would have finished sixth in the AL East—it seemed almost criminal that the Tigers had to prove their worth against them in the ALCS to reach the World Series. But Detroit pitching, which had glued itself back together in September, toughened up against the Royals by allowing just four runs and a .170 batting average in a three-game sweep.

BTW: The Royals emerged from a three-way battle with the Angels and surprising Minnesota Twins in September to win the AL West by three games.

Having conquered the American League with ease, the Tigers now awaited to find out who from the National League could possibly knock them off.

The San Diego Padres entered 1984 with 15 years of existence—only one of which had resulted in a winning record. But the 1984 edition was no longer the infant Padres of lore, teams that played depressing baseball in drab brown-and-yellow uniforms before small crowds at voluminous San Diego Stadium.

The current-day Padres were a talented mix of postseason-enriched veterans (Steve Garvey, Graig Nettles, Goose Gossage), rising stars (Tony Gwynn, Kevin McReynolds, Alan Wiggins), an aceless yet steady starting rotation (led by Eric Show and Ed Whitson) and a veteran manager (Dick Williams) who could forge victories out of any unit—all wearing bright fast-food colors for a franchise owned by the founders of McDonald’s.

BTW: Ray Kroc, who had bought the Padres in 1974, died shortly before the 1984 season began; his wife Joan took over as the official team owner.

After threatening to become a threat under Williams in 1982-83—two seasons in which San Diego finished each at an even 81-81—the Padres made good in 1984 against weakened NL West competition, emerging as the only team in the division to finish above .500 at 92-70. Garvey hit .284 with only eight home runs, but was flawless on defense, making no errors in 1,319 chances at first base—a first for an everyday first baseman. Gwynn, playing his first full year at age 24, batted .351 to capture his first of eight NL batting titles. Wiggins stole 70 bases and scored 106 runs. Gossage backed up the unwavering rotation with 10 wins, 25 saves and a 2.90 ERA.

With little tradition to speak of, the Padres were hardly the sentimental favorites in the NLCS. That distinction clearly belonged to the NL East-winning Chicago Cubs, making their first postseason appearance in nearly 40 years.

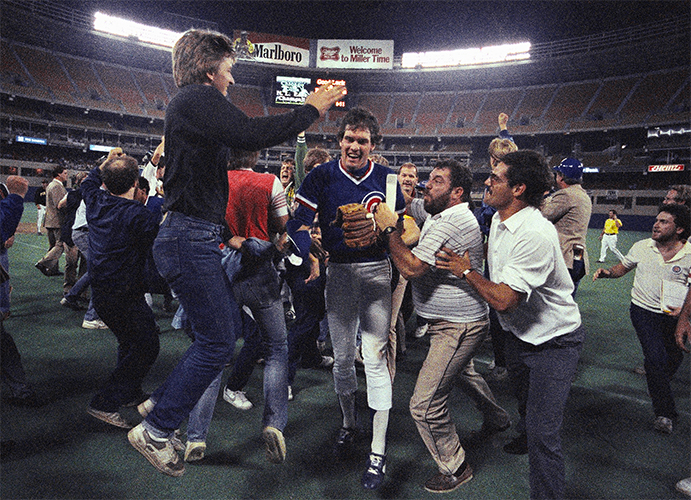

NL MVP Ryne Sandberg is accompanied off the field by delirious Chicago fans who made the trip to Pittsburgh to see the Cubs clinch their first postseason berth since 1945. (Associated Press)

The Cubs would make their only campaign above the .500 mark between 1977-89 highly worthwhile. Starring on this one-year wonder was second baseman Ryne Sandberg, an unassuming presence who after a few quiet years in Chicago suddenly transformed himself into an all-around force once manager Jim Frey prodded him to become more of a power hitter. A responsive Sandberg stopped chopping ground balls and started lining them all over the place, and the results were frightening for opponents: A .314 batting average, 36 doubles, 19 triples, 19 home runs, 84 RBIs and 32 steals. Additionally, Sandberg won the first of nine straight Gold Gloves at second base.

But Dallas Green—who three years earlier traded in his combative existence as Philadelphia manager for the general manager’s role in Chicago—needed something more to push the Cubs over the top, and made two pivotal midseason trades toward that goal. He acquired one starting pitcher in veteran Dennis Eckersley, then another in Rick Sutcliffe, languishing at Cleveland—where it was easy to do so—with a 4-5 record and 5.15 ERA. Eckersley’s 10-8 record with the Cubs was misleading when considering his fine 3.08 ERA, but there was no mistaking Sutcliffe’s numbers; his 16-1 record and 2.69 ERA at Chicago provided the final turn of the key to unlocking the Cubs’ 1984 success, as Chicago stormed past a promising New York Mets squad (loaded with 19-year-old rookie pitcher Dwight Gooden and 22-year-old sophomore slugger Darryl Strawberry) to win the NL East by 6.5 games.

BTW: The Cubs’ trade for Sutcliffe was certainly a classic case of “the future is now;” they dealt youngsters Joe Carter and Mel Hall to the Indians to get him…Sutcliffe became the first pitcher to split 20 victories between both leagues since 1945 when, ironically, Hank Borowy achieved it pitching the second half of the season for the World Series-bound Cubs.

Playing at a historic Wrigley Field adorned by ivied walls, bleacher bums and broadcaster Harry Caray’s colorful antics, the winning—and winsome—Cubs became an infectious sell for the millions who caught them on their nationwide cable outlet, WGN.

By comparison, the lack of tradition the San Diego Padres brought to the NLCS against the Cubs must have made them feel like unwanted party guests. No matter, Chicago whooped it up at home in the first two games, crushing the Padres by scores of 13-0 and 4-2. Flying back to San Diego with three games to win one, the Cubs boisterously readied for the kill, while the emotionally comatose Padres arrived back in town surprised to find a raucous fan base ready to stand them back on their feet. The overwhelming support was just the jumpstart the Padres needed, storming back to win all three games at home, each after spotting the Cubs with early leads. It was the Cubs’ turn to go numb, living a disbelieving end to a season suddenly gone south all the way to the Mexican border.

For the Padres, the hard part still lay ahead: Overcoming the Detroit Tigers.

These Things Happen in Threes

After winning the first two NLCS games at Chicago, the Cubs lost the next three games and the NL pennant when the Padres advanced with late rallies.

Unanimously cast as big-time World Series underdogs, the Padres and their delusions of grandeur could have actually been realized against the AL juggernaut. But one thing got in the way: Starting pitching.

So reliant all year, the Padres rotation completely self-destructed against Detroit. Mark Thurmond opened Game One and lasted five innings in a 3-2 loss; his effort would easily be the workhorse showing of the series. Game Two starter Ed Whitson lasted two-thirds of an inning. Tim Lollar was pulled before the end of the second inning in Game Three. Eric Show was removed before three innings were up in Game Four. Thurmond, perhaps inspired in the worst way, returned to the mound in Game Five and lasted all of a third of an inning. When the damage was totaled up, the Padres’ rotation ERA in the series was listed at an abysmal 13.94.

The San Diego bullpen—already taxed from overwork against the Cubs—had no choice but to earn more overtime pay and give Padres hitters a chance to overcome early Detroit leads. San Diego managed one comeback with a 5-3 Game Two victory, but otherwise the Padres were asking for it against the almighty Tigers.

Just by himself, Jack Morris nearly doubled the total number of innings pitched by the entire Padres rotation by tossing complete game victories in Games One and Four. Alan Trammell homered twice and knocked in all four runs for Morris in a 4-2 Game Four win; Kirk Gibson homered twice himself in the Game Five clincher, an 8-4 victory wrapped up by Willie Hernandez’s second Series save in the ninth.

As Detroit fans went wild in celebration outside of Tiger Stadium—too wild, with a slew of arrests and 83 casualties including one death—Sparky Anderson toasted his players inside with his catchphrase for the season, “Bless You Boys,” thanking the Tigers for following his five-year script to a steamrolling conclusion.

Forward to 1985: The Missouri Stakes Blown calls and hot tempers put a controversial finish to the “I-70 Series” between Kansas City and St. Louis.

Forward to 1985: The Missouri Stakes Blown calls and hot tempers put a controversial finish to the “I-70 Series” between Kansas City and St. Louis.

Back to 1983: The Good, the Old and the Ugly The Baltimore Orioles (good) fight off unlikely foes in the Philadelphia Phillies (old) and the Chicago White Sox (ugly).

Back to 1983: The Good, the Old and the Ugly The Baltimore Orioles (good) fight off unlikely foes in the Philadelphia Phillies (old) and the Chicago White Sox (ugly).

1984 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1984 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

1984 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1984 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

The 1980s: Corporate Makeover Baseball enjoys a healthy boom on several fronts, with increased attendance, corporate sponsorship and memorabilia sales; players also continue to enjoy skyrocketing salaries, but some abuse their newfound riches by delving into illegal drugs.

The 1980s: Corporate Makeover Baseball enjoys a healthy boom on several fronts, with increased attendance, corporate sponsorship and memorabilia sales; players also continue to enjoy skyrocketing salaries, but some abuse their newfound riches by delving into illegal drugs.