THE YEARLY READER

1987: Dome Sweet Dome

The Minnesota Twins, displaying a schizophrenic personality unlike any seen in baseball, lose horribly on the road but are unbeatable at home; it’s all good enough to give the Twin Cities their first World Series title.

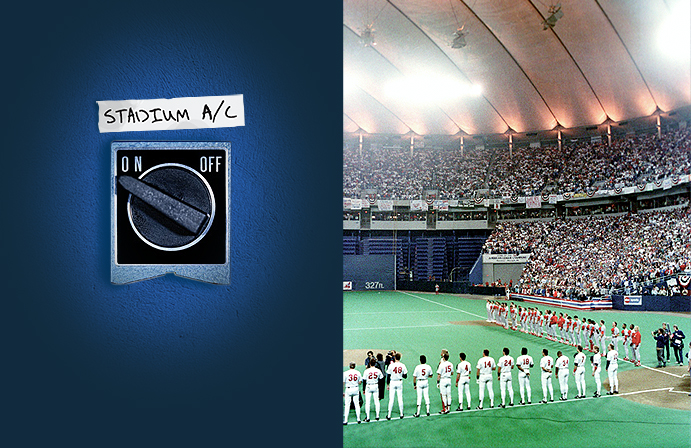

The Minnesota Twins and St. Louis Cardinals line up before the first game of the 1987 World Series at the Minneapolis Metrodome, where the Twins were virtually unstoppable—perhaps because of a stadium employee who later confessed to making the indoor air blow toward the fences whenever the Twins came to bat. (Associated Press)

From the day it first opened in 1982, the Hubert H. Humphrey Metrodome in Minneapolis was ridiculed, heavily criticized and cursed at by most everyone who came to play the Minnesota Twins. Visiting teams detested the Metrodome’s unnatural features: A super-bouncy artificial turf, a white, glare-inducing fabric roof, bandbox dimensions and a tall right-field wall covered with what appeared to be the world’s largest garbage bag. Purists watching from the seats or on television took one look at the Metrodome and prayed that ballpark architecture had reached its nadir.

There was one thing opponents didn’t mind when coming to the Metrodome: The Twins themselves, a young and ineffective group labeled the “Twinkees” for much of the 1980s to date. That changed in 1987 when the Twins suddenly grew up together, shed their pushover image and took advantage of the Metrodome—illicitly or otherwise—overcoming the woes of the road to capture the franchise’s first world championship in 63 years.

The Twins’ early years at the Metrodome threatened to be among their last in Minnesota. The Griffith family, which had owned the franchise since its preteen days as the Washington Senators, had an escape clause in the Metrodome lease if the team failed to average 1.5 million fans a season over any three-year period. After losing 102 in 1982 and 92 more in 1983, the fledgling, no-name Twins needed to sell 2.4 million tickets in 1984 to keep the Griffiths locked in. Threatening to take the team to St. Petersburg, Florida—every owner’s favorite bargaining chip—the Griffiths were bought out midway through 1984 by Minneapolis banker Carl Pohlad, and the future of baseball in the Twin Cities was saved.

Pohlad inherited a facility deemed the worst in baseball, but also took over a blossoming roster born out of the misery of 1982. That roster included southpaw Frank Viola and sluggers in third baseman Gary Gaetti, outfielder Tom Brunansky and first baseman Kent Hrbek, who grew up in the shadows of old Metropolitan Stadium.

BTW: The Twins’ 1982 roster included 11 rookies, many of whom would star in 1987.

The power-laden lineup was given immense flair with the 1984 arrival of center fielder Kirby Puckett, a rampaging bowling ball of a player with his curiously short, stocky and very powerful physique. Puckett’s dynamic play both at the plate and in the outfield was instantly evident, and his quick conversion to power—he hit no home runs in 1984, four in 1985 and, suddenly, 31 in 1986—promptly got him promoted to the game’s superstar elite.

Rounding out the Twins for 1987 was the man tagged to lead it all—manager Tom Kelly. A complete antithesis to the colorful nature of his players, the quiet, emotionally one-note but arid-witted Kelly was happy to melt into the background and let his players take all the credit. And like most successful young managers, the 36-year-old Kelly was there due to a quick and forgettable playing career in the bigs, batting .181 in minimal action for the 1975 Twins.

BTW: Kelly had taken over for Ray Miller late in 1986 and went 12-11 to avoid a last-place finish.

Ever more maturing and confident, the Twins fought it out in an exceptionally tight-knit American League West that, once more, lacked no powerhouse element; only 10 games would ultimately separate first place from seventh. Minnesota held onto the lead for much of the year and, by season’s end, outlasted by two games the Kansas City Royals, emotionally drained with the loss of beloved manager Dick Howser—who died of brain cancer during the season.

The Twins took the natural presumption that big league teams play better at home to a schizophrenic level. At the Metrodome they were monsters, the majors’ best at 56-25. Yet suspicions abounded. In a year where a sudden outbreak of home runs led to bats everywhere being confiscated and checked for cork, AL opponents had a different theory for the Twins’ stunning homespun success. The team was repeatedly accused of turning on the Metrodome’s air vents that kept the roof aloft—but only when the Twins came to bat, allegedly creating an advantageous wind pattern that gave fly balls a little more of a push towards, and possibly beyond, the outfield wall.

On the road, it was a far different story. The Twins were the AL’s third worst at 29-52, winning only nine games away from the Metrodome after the All-Star break. Claims of cheating were fewer and far between, but the Twins got caught anyway; veteran pitcher Joe Niekro was ejected in an August game at California when he was collared red-handed on the mound with an emery board. (Niekro claimed he was using the board to file his nails in the dugout. League officials chuckled and levied a 10-game suspension.)

The overall ledger for the Twins did not make for an impressive postseason participant. They gave up more runs than they scored. The pitching staff’s earned run average was 4.63, tied for 11th in the AL. Their starting rotation, beyond Viola (17-10, 2.90 ERA) and once-and-current Twin Bert Blyleven (15-12, 4.01) was a disaster. One-time stalwarts Niekro and Steve Carlton, both 42 years of age and acquired during the year, were no help as they combined for a 5-14 record and 6.40 ERA. But there was no doubting the Twins’ ability to power the ball. The three sluggers from the Class of ’82—Gaetti, Brunansky and Hrbek—ganged up for 97 home runs and 284 runs batted in. Puckett, batting .332 with a league-high 207 hits, added 28 homers and 99 RBIs.

A Tale of Two Twins

Beyond the record, a statistical breakdown of the Twins’ home and road performance offers up a few more clues as to why they were kings at the Metrodome—and paupers away from it.

The Detroit Tigers were initially thrilled to be given the Twins to start the ALCS. The AL East champs had prevailed in a much tougher division where four teams posted better records than Minnesota. They had, with a week to go, rebounded from a 3.5-game deficit against front-running Toronto, doing so in the most authoritative way possible—winning the season’s final three games head-on against the Blue Jays, who completed a year-end nosedive with seven straight losses.

The Tigers had hitting everywhere, a prodigious force that smashed a team record 225 home runs—and were led by, arguably, the AL’s player of the year in shortstop Alan Trammell (.343 average, 28 home runs, 105 RBIs). Unlike the Twins, Detroit had the pitching, anchored as always by Jack Morris (18-11, 3.38 ERA). Some believed this was a better team than the 1984 Tigers that breezed to a World Series title—and they were one of the few teams to fare well against the Twins at the Metrodome, taking four of six contests during the regular season.

But the Metrodome they came back to in October would be a much different place.

Every seat was filled with avid Twins fans that had waited nearly a generation to see their team return to the postseason. They created a sea of confetti by waiving white “Homer Hankies” and—most noticeably—stirred up so much noise that reverberated through the indoor venue, decibel readings taken on the field showed the din to be louder than a Boeing 747.

The rowdiest Tiger Stadium crowds had nothing on this. Detroit was floored, as the Twins summarily dismantled the Tigers in the first two games at the Metrodome. Common wisdom presaged a Tiger rebound against Minnesota road kill for the next three games at Detroit, but the shell-shocked Tigers never recovered from the Metrodome experience, while the Twins never stopped hitting. Minnesota won two of the three and the AL pennant, four games to one, totaling seven homers and 34 runs in five games off Morris, Doyle Alexander (who lost two ALCS games after going 9-0 as a Tiger midseason acquisition) and company. Little was needed of the Twins’ rotation beyond Viola and Blyleven, who grouped to start all four Minnesota victories.

The challenge of conquering the Twins—and the Metrodome—now fell upon the National League champion St. Louis Cardinals.

Two years after winning the NL pennant—and one year after their offense went AWOL with a .236 team batting average and 58 home runs (resulting in a 79-82 record)—the Cards reawakened at the plate in 1987 and captured their third NL flag in six years.

While everyone else in the league was busy shattering home run records, the Cardinals bucked the trend and continued to win as they had all decade—using speed, defense and sharp pitching. Whitey Herzog’s Redbirds took the NL East by three games over the defending champion New York Mets—hung over from their magnificent 1986 performance through injuries, drug problems for Dwight Gooden and a general lack of destiny.

The Cardinals once more drove opposing fielders crazy with a non-stop barrage of line drives, infield hits and stolen bases. Vince Coleman stole over 100 for the third straight year. Fellow outfielder Willie McGee smacked 37 doubles, 11 triples and 11 home runs while knocking in 105 runs. Ozzie Smith set career highs with 104 runs, 40 doubles, 75 RBIs and a .303 batting average—all without a single homer—while continuing his usual wizardry at shortstop.

Although the Cardinals predictably ranked dead last in the majors with 94 homers, they possessed one of the season’s most fearsome slugging threats in Jack Clark. The first baseman, far more patient at the plate in search of the big blast (as evidenced by 136 walks and 139 strikeouts over 131 games), clubbed 35 out with 106 RBIs before a September injury ended his season early—and crucially kept him sidelined for the postseason.

Cardinal Comeback Players of the Year

To say the Cardinals suffered through an off-year in 1986 was an understatement, finishing dead last in the majors in almost every major offensive category. The core of the Cardinals’ batting order turned the switch back on in 1987, as shown below.

Injuries also played havoc with the St. Louis pitching staff—most graphically with an early-season freak incident in which starter John Tudor had his leg broken after being crashed into by New York catcher Barry Lyons, chasing a foul pop-up into the Cardinals dugout. Amazingly, despite the Cardinals’ 95 regular season wins, no single pitcher won more than 11—though Tudor might have pushed 20 had it not been for his injury (in 16 starts before the mishap, Tudor was 10-2). As always, the St. Louis bullpen played a vital and stingy role in snuffing out opponents’ late rallies.

The NL West champ San Francisco Giants were, much like the Twins, recent 100-game losers converted to young and cocky contenders. Roger Craig, the former Detroit pitching guru now managing his second year at San Francisco, motivated his players to embrace the arctic, wind-swept tundra of Candlestick Park; after all, it’s the other teams who despised coming to play there. The new Giants cast fully absorbed Craig’s new attitude, including 23-year-old first baseman Will Clark—who introduced himself to the majors a year earlier by crushing a 400-foot-plus home run to center field off Nolan Ryan.

BTW: After hitting 11 home runs in a mildly successful 1986 rookie campaign, Clark exploded for 35 homers and a .308 average in 1987.

A highly acrimonious NLCS between the Giants and Cardinals went the distance. Tensions developed before the series even began as the Giants, citing a four-game sweep of the Cardinals at St. Louis the last time they met, were publicly brash about their chances. After the series began, the Cardinals were further irked by the antics of San Francisco outfielder Jeff Leonard, who called St. Louis a “cowtown” and celebrated home runs in each of the series’ first four games with a “one flap down” trot—jogging the bases with his left arm fully lowered to his side.

After taking a three games-to-two lead back to St. Louis, the Giants were shut up and shut down by Cardinals pitching—which blanked San Francisco in Games Six and Seven to win the pennant by 1-0 and 6-0 scores.

The Twins’ Dan Gladden belts the World Series’ first grand slam in 17 years during Game One at Minnesota; note the Metrodome air duct at left, a source of controversy during the season. (Associated Press)

As luck would have it for the Minnesota Twins, they received home field advantage against St. Louis for the World Series, giving them four home games against the Cardinals’ three in a seven-game scenario.

The Twins lost all three games at St. Louis.

They won all four at the Metrodome.

In a microcosm of their Jekyll-and-Hyde regular season campaign, the Twins opened at home with 10-1 and 8-4 routs of the Cardinals, scoring early and often to neutralize the St. Louis speed game—then fell quiet down the Mississippi for Games Three, Four and Five at St. Louis, scoring just five runs on 18 hits over three losses to the Cardinals. Then it was back home for Games Six and Seven, with the noise ear-shattering as ever and the Hankies flying more wildly within the packed house. This time, the Cardinals gave it their best—holding the lead in both games through the middle of the fifth inning. In Game Six, the St. Louis lead was laid to waste by consecutive four-run rallies, capped by a Kent Hrbek grand slam for an 11-5 win; a more taut Game Seven affair was tipped in the Twins’ favor with single runs in the fifth, sixth and eighth innings, erasing a 2-1 Cardinal lead.

Fittingly for the Twins, the 1987 World Series was the first in which no team won on the road.

Every Twin seemed to contribute. No one player badly slumped, and seven different Twins hit one homer each. The Cardinals, who hit only two homers, horribly missed Jack Clark—to say nothing of their pitching staff, which registered a bruising 5.64 ERA against the Twins.

Following the World Series, Major League Baseball checked out and could not prove the allegations of the Metrodome air vents creating indoor winds to aid the Twins’ offense. But in 2003, a former Metrodome superintendent admitted that he had, in the late innings of close games in 1987 and other years, ordered the air to blow out when the home team hit. Even if the airflow gave the Twins an advantage—later tests proved inconclusive—he felt no shame. To him, every ballpark had its own brand of home field advantage, and this would be the Metrodome’s.

Forward to 1988: Roy Hobbs in Dodger Blue Kirk Gibson makes like Robert Redford and gives the Los Angeles Dodgers a storybook ending.

Forward to 1988: Roy Hobbs in Dodger Blue Kirk Gibson makes like Robert Redford and gives the Los Angeles Dodgers a storybook ending.

Back to 1986: An October for the Ages A historic postseason full of comebacks and collapses takes on legendary proportions thanks to Bill Buckner.

Back to 1986: An October for the Ages A historic postseason full of comebacks and collapses takes on legendary proportions thanks to Bill Buckner.

1987 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1987 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

1987 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1987 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

The 1980s: Corporate Makeover Baseball enjoys a healthy boom on several fronts, with increased attendance, corporate sponsorship and memorabilia sales; players also continue to enjoy skyrocketing salaries, but some abuse their newfound riches by delving into illegal drugs.

The 1980s: Corporate Makeover Baseball enjoys a healthy boom on several fronts, with increased attendance, corporate sponsorship and memorabilia sales; players also continue to enjoy skyrocketing salaries, but some abuse their newfound riches by delving into illegal drugs.