THE YEARLY READER

1996: Here’s Spittin’ at You, Kid

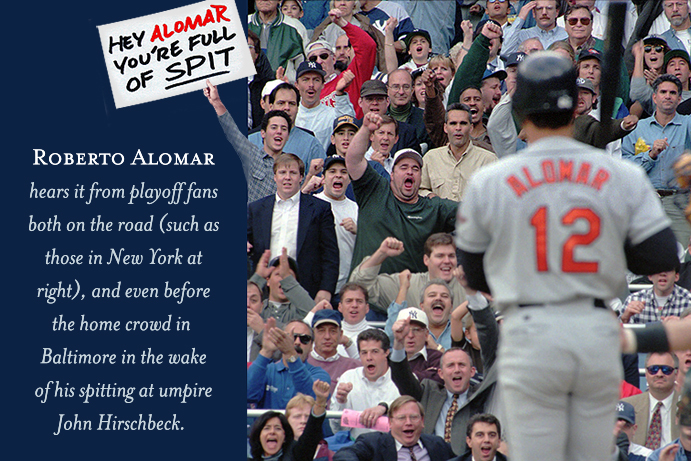

The postseason takes on a tabloid-style existence with Roberto Alomar‘s controversial inclusion into the playoffs, and a young fan in the right-field bleachers who saves the day—and maybe the season—for the New York Yankees.

(Associated Press)

It is often bragged that image is everything, but that was all too unfortunate for Roberto Alomar, whose perception as All-Around Good Guy turned into All-Around Jerk overnight.

Baltimore Orioles teammates saw number 12 on the back of Alomar’s jersey; everyone else saw a bull’s-eye target. Fans, umpires, the court of public opinion—they all believed that the Orioles, and especially Alomar, did not deserve to be in the postseason, and desperately wanted payback. Umpires threatened to strike, fans booed Alomar until the decibel meter cracked, and columnist after columnist raged away on their laptops. The Orioles simply yawned and rolled ahead—and so did Alomar.

Poetic justice would ultimately be served upon Alomar and the Orioles. Not by the courts. Not by the umpires’ union. Not even by the commissioner, interim or otherwise. It would instead be administered by a 12-year-old kid from New Jersey who decided to skip school and take a seat with some friends behind the right-field wall at Yankee Stadium.

Since his introduction to the big leagues in 1988 at age 20, Roberto Alomar had quickly established himself as graceful both on the field and in the clubhouse, a slick-fielding second baseman with great range, speed and attitude. Worse for the opposition, Alomar’s batting skills had caught up with those of his glove, consistently batting .300 with emerging power. After five years in Toronto, Alomar signed up with the Orioles for 1996, and his offense immediately blossomed into superstar terrain—producing career highs with a .328 batting average, 132 runs, 43 doubles, 22 home runs, 94 runs batted in and 90 walks.

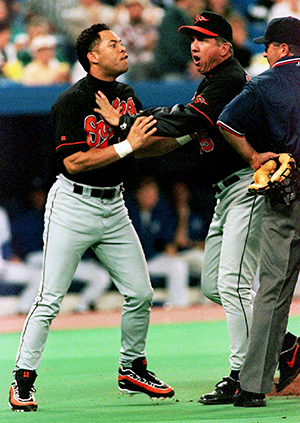

The spit heard ‘round the world: Baltimore’s Roberto Alomar lets loose on umpire John Hirschbeck while Oriole manager Davey Johnson desperately tries to calm him down. (Associated Press)

In his first at-bat of the series, Alomar took a called third strike by umpire John Hirschbeck—and suffered a meltdown worthy of Chernobyl. He let loose with a torrent of abusive language and then, in the midst of being held back by manager Davey Johnson, spat point blank at Hirschbeck’s face. Alomar claimed the source of his rage came when, after looking back at Hirschbeck on strike three, he was told, “You’d better swing at that pitch.” But Alomar wouldn’t air that accusation for a few months; instead, it was hours after the incident that Alomar, still stewing in the Orioles locker room, dug deeper the grave on his congenial reputation by suggesting Hirschbeck had grown “bitter” since the recent death of his son to a rare brain disorder. When Hirschbeck got wind of those comments the next day, he stormed hell-bent into the Orioles clubhouse ready to “kill” Alomar, and had to be physically escorted away.

Alomar was quickly slapped with a five-game suspension, but he quickly appealed and was granted a stay of execution—to the utter dismay of Hirschbeck and every other major league umpire. Back in uniform, Alomar became the hero of the Orioles’ second-to-last regular season game when he clocked a game-winning, 10th-inning homer against the Blue Jays—helping to clinch Baltimore an American League wild card spot.

BTW: In truth, the Orioles’ winning of the wild card spot was all but academic; their magic number with two games to go was one.

The Orioles’ path to the postseason, suddenly mired in controversy, capped an otherwise mammoth AL East race between two affluent titans trying to outspend one another for first place. The Orioles failed in that quest, playing second fiddle to the New York Yankees.

It had been a miserable last 15 years for George Steinbrenner and the Yankees, who had fallen from annual World Series favorite to contenders, and then pretenders. Impatient as ever, Steinbrenner became a victim of his early successes and could no longer forge triumph through chaos, no matter how hard he tried. And try hard he did. Steinbrenner made 13 managerial changes over a 12-year period and continually collected over-the-hill veterans for blue-chip prospects or major free agency bucks. When they didn’t produce to his satisfaction, Steinbrenner ridiculed them through the press, or worse—as when he paid $40,000 to a mob-tied gambler to dig up dirt on Dave Winfield, costing him a three-year suspension from baseball. Steinbrenner’s act had grown embarrassing if not tiresome, and he was reduced in the public mainstream to a faceless caricature on Seinfeld, dumb enough to hire George Costanza to the Yankees front office.

But a funny thing began to happen in 1992. Steinbrenner showed unprecedented willpower in hiring a manager—Buck Showalter—who made it not just through one season, but four. More importantly, Steinbrenner kept his hands off the farm system, allowing his latest collection of promising prospects to grow and graduate to the majors wearing Yankee pinstripes.

BTW: Showalter left on his own after 1995 to take over the expansion Arizona Diamondbacks.

Patience bred success. The Yankees improved at a healthy clip through the early 1990s, finally returning to the postseason in 1995 as a wild card. In 1996, Steinbrenner found his team in possession of something none of his bucks could possibly buy: Destiny.

Steinbrenner’s cadre of young, homegrown Yankees all matured at once into big-time stars. The elder statesman of this new generation was 27-year-old center fielder Bernie Williams, whose gangly physique recalled Dave Winfield—and like the ex-Yankee developed into the team’s biggest offensive threat with a .305 average, 29 home runs and 102 RBIs. Starting pitcher Andy Pettitte, whose left-handed Louisianan roots echoed another former Yankees star in Ron Guidry, won an AL-high 21 games in just his second year. And at shortstop was 22-year-old rookie Derek Jeter, a prodigy so highly valued by the Yankees, they gave him one of only two single-digit uniform numbers not retired by the team, the others having previously been worn by immortals such as Ruth, Gehrig, DiMaggio and Mantle. Jeter’s smart, scintillating defense backed by a .314 batting average in 1996 suggested that he might be the last Yankee to wear no. 2.

BTW: Jeter was the first no. 1 draft choice by the Yankees since Thurman Munson—in 1968—to fulfill his promise in pinstripes.

Alongside the youngsters, the veterans clicked as every move the Yankees made turned to gold. Tino Martinez was acquired to replace the retired Don Mattingly at first base and led the Yankees with 117 RBIs. Jimmy Key, a year after major rotator cuff surgery left doctors skeptical that he could pitch again, put together a 12-11 mark. Fellow starter David Cone made an equally successful recovery from a series of blood clots in his pitching arm. And Dwight Gooden—given a chance by Steinbrenner after drugs had gotten him kicked out of baseball in 1995—threw an inspirational no-hitter against the high-powered Seattle Mariners in May, and finished at 11-7.

Leading the Yankee parade in the dugout was manager Joe Torre, hired after six uninspiring years at St. Louis. The New York media initially lambasted Torre as another one of Steinbrenner’s retread yes-men, but his calm, poker-faced attitude perfectly won the players over—and the Boss left him alone.

The Yankees took a healthy double-digit AL East lead into July but began sliding in August, allowing the Orioles to ride up on their heels—initiating an all-out war of big wallets between the two teams as they would spend, trade, spend, acquire and spend again.

Even before the budget-busting race began, the Orioles were already choked with offense, as led by Alomar, Rafael Palmeiro (39 home runs, 142 RBIs), Bobby Bonilla (28, 116), Cal Ripken Jr. (26, 102) and leadoff batter Brady Anderson, who, of all people, exploded for 50 homers. The late-season moves, which brought over Todd Zeile and Pete Incaviligia from Philadelphia—and former Baltimore All-Star Eddie Murray back from Cleveland—beefed up the prodigious offense to an outrageous level; by September, the Orioles could field a lineup in which all nine batters had hit at least 20 home runs for the season, undoubtedly a major league first. Strangely, the Orioles’ front office did little to fix up its wretched pitching staff, weighing the team down with a 5.14 earned run average; thus, the Orioles’ challenge to the Yankees fell short. In defeat, however, they garnered a worthwhile consolation prize in the AL wild card, thanks in part to Roberto Alomar’s last-weekend heroics—spit, sock and all.

BTW: Power-wise, it all spiked for the Orioles in 1996; their 257 total home runs set an all-time record that would be topped the next year by Seattle, while Brady Anderson’s 50 homers stood out among a career in which he hit no more than 24 in any of 14 other seasons.

Major league umpires, livid that Alomar’s penalty for his actions against John Hirschbeck was too short (five games), not costly (no fines) and not timely (to be served at the beginning of 1997, not during the 1996 playoffs), mulled a boycott right up to the postseason’s first pitch; it took an injunction from a Federal court to get them back on the field. Alomar’s ensuing performance in the ALDS against the powerful Cleveland Indians—owners of the majors’ best record at 99-62—only made the men in blue seethe more. In the decisive Game Four at Cleveland, Alomar hit a two-out, two-strike, run-scoring single to tie the Indians in the ninth—and batting leadoff in the 12th, slammed a home run that would win the game and the series, three games to one.

Alomar, by now, had gotten the message of what he had wrought. Being virulently booed at Cleveland was no surprise, but he’d also heard catcalls from his own fans in Baltimore. He released a prepared statement of apology—some umpires believed he hadn’t written it—and agreed to donate $50,000 to help fight the brain disease that took the life of Hirschbeck’s son. A merciful Hirschbeck accepted Alomar’s mea culpa and urged everyone to move on.

The apology had been issued, but justice had yet to served. It would be waiting for Alomar and the Orioles in Game One of the ALCS at Yankee Stadium.

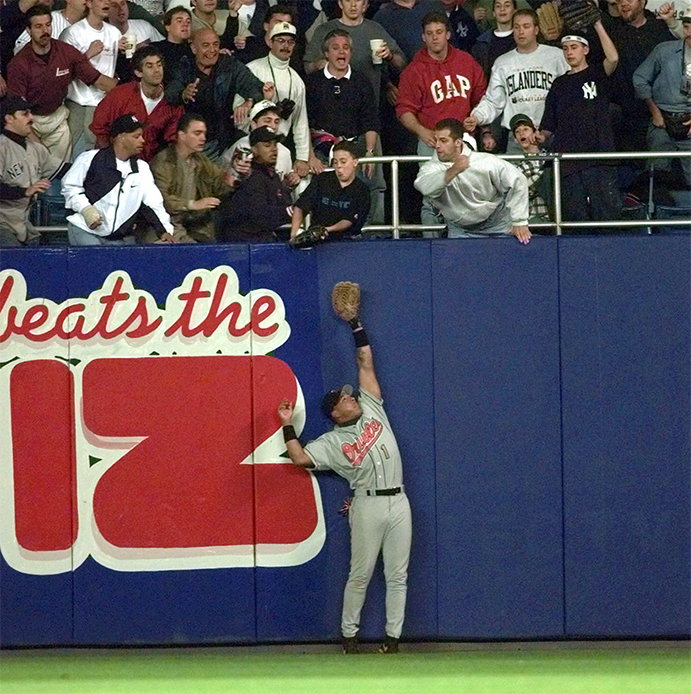

Twelve-year-old Yankee fan Jeffrey Meier steals Derek Jeter’s fly ball away from Baltimore outfield Tony Tarasco, who will bitterly plead fan interference to no avail. Jeter’s Meier-assisted homer changed the complexion of the ALCS, won by New York. (Associated Press)

The Yankees, having dispensed of another high-powered foe in the Texas Rangers during the first round, dueled with the Orioles in a tight ALCS opener. Trailing 4-3 with one out in the eighth, Derek Jeter strode to the plate against young flame-throwing Baltimore reliever Armando Benitez. The rookie shortstop lofted the first pitch towards the right-field bleachers; Orioles outfielder Tony Tarasco backed up flat against the wall, looked and reached up…and then it was gone, plucked out of the air by the wayward glove of 12-year-old Jeffrey Meier, reaching over from behind the wall. Umpire Rich Garcia, racing down the right-field line, ruled no interference and gave Jeter the home run. Tarasco and manager Davey Johnson—holding back their spit—argued bitterly, but to no avail. (Garcia later viewed a replay and admitted he had made the wrong call.) The game was tied, extra innings commenced and, in the 11th, Bernie Williams clobbered a deep fly no outfielder had a chance at to win the game, 5-4.

BTW: The Texas Rangers, making their first-ever postseason appearance, were ousted by the Yankees at the ALDS in four games despite Juan Gonzalez’s record-tying five home runs.

While Meier became the toast of New York—making the standard Big Apple media circuit the next day with Good Morning America and David Letterman, among others—the Orioles evened the series with a 5-3 win, though they brooded that Meier had kept them from taking a 2-0 series lead back to Baltimore.

From there, the Orioles would only have themselves to blame. They had lost all six games to the Yankees at Camden Yards during the regular season, and it was at Camden Yards where they would lose all three ALCS contests to bow again to the Yankees—this time for good. In a five-game ALCS victory, the Yankees hammered away at weak Baltimore pitching for 10 home runs, including three from Darryl Strawberry—like Dwight Gooden, another ex-New York Mets refugee from substance abuse hell.

Home Field Disadvantage

Throughout 1996, the Orioles took on the Yankees at home nine times, including three ALCS matchups—and lost every one of them. Here’s the breakdown of Baltimore’s 0-9 ledger against the eventual World Series champions.

With Alomar and the Orioles past tense, all eyes turned to the World Series, and whether the Yankees could stop a thundering rolling stone in the Atlanta Braves.

The defending world champions had sailed through another first-class regular season thanks to superb starting pitching from their Big Three: Greg Maddux (15-11, 2.72 ERA), Tom Glavine (15-10, 2.98) and especially John Smoltz, who enjoyed a career year with a 24-8 record, 276 strikeouts and a 2.94 ERA. At the plate, the Braves’ assets were many, highlighted by 24-year-old switch-hitter Chipper Jones, reaching statistical stardom with a .309 average, 30 home runs and 110 RBIs.

After sweeping National League wild card entrant Los Angeles in three games, the Braves advanced to the NLCS and quickly found themselves in trouble with the NL Central-winning St. Louis Cardinals. Managed by former Oakland skipper Tony La Russa—who brought along a number of A’s players and coaches with him—the Cardinals pinned the suddenly droning Braves against the ropes with a 3-1 series lead, and looked primed to deliver the knockout blow at home for Game Five. Then Atlanta rebounded—like Popeye after spinach. They clobbered the Cardinals 14-0 in Game Five to stay alive; took Game Six behind Maddux, 3-1; and, in Game Seven, laid another trouncing upon St. Louis, this time by a 15-0 count. The Cardinals never knew what hit them.

And neither would the Yankees for the first two games of the World Series at New York.

Behind Smoltz in Game One, the Braves pummeled anew, 12-1 at Yankee Stadium. In Game Two, Atlanta managed just four runs, but it was easily enough for Maddux—who shut the Yankees down, 4-0. Having outscored the opposition by an incredible 48-2 over their last five games, the Braves looked indomitable—and were headed back to Atlanta for the next three.

BTW: The Braves’ Andruw Jones, 19, introduced himself to the nation in Game One with two home runs, making him the youngest player ever to go deep in a World Series game.

On the ropes—if not crawling back to the canvas—it was the Yankees’ turn to fight back. Behind David Cone, they silenced the Braves 5-2 in Game Three, and then, after Atlanta threatened another rout with an early 6-0 lead in Game Four, the Yankees found their best new friend since Jeffrey Meier in umpire Tim Welke—who got in the way of Atlanta outfielder Jermaine Dye, who had to detour around Welke and therefore couldn’t reach a pop-up foul hit by Derek Jeter. It was a moment that would confirm Yankee destiny. Still alive, Jeter singled and ignited a three-run rally to put the Yankees back in the game; two innings later, they dramatically tied it when Jim Leyritz grabbed hold of a hanging slider from Atlanta closer Mark Wohlers and slammed a three-run homer. New York completed the World Series’ biggest single-game comeback since 1929—and tied the series—when it notched two runs in a two-run, 10th-inning rally.

The Yankees completed their improbable three-game sweep to spoil the Launching Pad’s last party in Game Five, with Pettitte outdueling Smoltz, 1-0; The lone run came when Charlie Hayes’ fly ball was dropped by Atlanta center fielder Marquis Grissom—distracted by Dye, running in too close from his left.

BTW: The 31-year-old Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium was due to be razed to make room for Turner Field’s parking lot in 1997.

Absent for 18 years from baseball’s top podium, the Yankees realized their magical return to championship form at Yankee Stadium in Game Six. They knocked Maddux for three runs in the third inning, and after Jimmy Key made the New York lead stand up through six innings, the game was turned over to the Yankees bullpen—a very strong unit which had helped limit the Yankees to just three blown leads all year after the sixth inning, and was led by closer John Wetteland and his heir apparent in Panama-born Mariano Rivera. The Braves closed the score to 3-2 and put the tying and go-ahead runs on base in the ninth, but Wetteland prevailed—and earned the Series MVP for saving all four New York victories.

The Yankee triumph was all the more emotional for manager Joe Torre, who during the year had lost one brother to a heart attack, while his other brother—former major leaguer Frank Torre—was successfully given a new heart just a day before the Game Six clincher.

BTW: The operation was performed by Dr. Mehmet Oz, who went on to daytime TV fame a decade later.

Yankee destiny would soon give way to a new Yankee dynasty, but for now the thrill of victory came to George Steinbrenner like a badly-needed coat of fresh paint. And for his players came the spoils, with the average winning share at $217,000.

And most certainly, sooner or later, Steinbrenner would have considered at least a half-share for Jeffrey Meier.

Forward to 1997: A Blockbuster of a Binge Florida Marlins owner Wayne Huizenga quickly builds up a winner—and just as quickly tears it apart.

Forward to 1997: A Blockbuster of a Binge Florida Marlins owner Wayne Huizenga quickly builds up a winner—and just as quickly tears it apart.

Back to 1995: Thanks to Cal, Hideo—and Sonia, Too Numerous feel-good moments rescue baseball from its most devastating work stoppage.

Back to 1995: Thanks to Cal, Hideo—and Sonia, Too Numerous feel-good moments rescue baseball from its most devastating work stoppage.

1996 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1996 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

1996 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1996 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

The 1990s: To Hell and Back Relations between players and owners continue to deteriorate, bottoming out with a devastating mid-decade strike—souring relations with fans who, in some cases, turn their backs on the game for good. Recovery is made possible thanks to a series of popular record-breaking achievements by ‘class act’ stars.

The 1990s: To Hell and Back Relations between players and owners continue to deteriorate, bottoming out with a devastating mid-decade strike—souring relations with fans who, in some cases, turn their backs on the game for good. Recovery is made possible thanks to a series of popular record-breaking achievements by ‘class act’ stars.