THE YEARLY READER

1997: A Blockbuster of a Binge

The slow, steady ascension of the Florida Marlins is accelerated up and over the top after a free-agent spending spree by owner Wayne Huizenga.

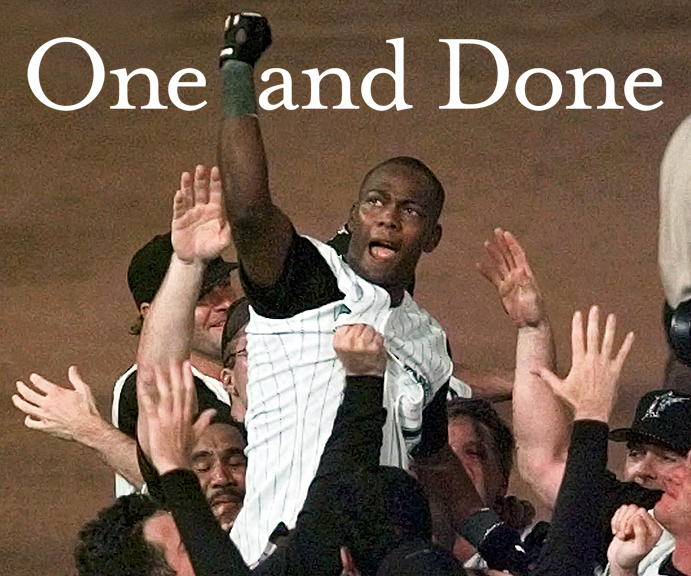

Edgar Renteria is lifted victoriously in the air after punching out the game-winning hit to give the Florida Marlins a seven-game World Series triumph over Cleveland. Because he was earning a minimal salary, Renteria would remain a Marlin in 1998; many of his teammates would not. (Associated Press)

Four months after winning the 1997 World Series, the Florida Marlins were honored by President Bill Clinton at the White House. Only 14 Marlins showed up. The other 11 were ex-Marlins—traded, released or lost to free agency.

And that was just the beginning.

Connie Mack had twice proven long ago that you could build a championship team over time and tear it down overnight. Wayne Huizenga proved with the 1997 Marlins that you could both build and tear apart a winner within an eye blink of baseball history. In that relative split second, Huizenga was both a hero and villain in Miami, and to the greater baseball populace represented all that was wrong with the game in the 1990s.

A determined 59-year old with not much hair but loads of business savvy and a commanding presence, H. Wayne Huizenga had conquered the world of garbage (Waste Management), movie rentals (Blockbuster Video) and had all but become king of South Florida pro sports. Applying his magic touch for quick success had worked well with the two teams he bought: The Miami Dolphins, an established NFL franchise with a winning tradition, and hockey’s Florida Panthers, who reached the 1996 Stanley Cup Finals in just their third year—and on its enthusiastic coattails were blessed with a new, publicly funded arena Huizenga badly wanted.

Huizenga’s patience, however, was a bit tested when it came to the Marlins, an expansion team he bought so he could book an additional 81 events a year at Pro Player Stadium—which he also owned. Through their first four years, the Marlins had failed to register a winning season while attendance shrunk to half of its inaugural year count—even after Huizenga widened payroll in 1996 with star free agent pitchers Kevin Brown and Al Leiter.

Knowing that finding success on the field meant competing with the powerful Atlanta Braves in the National League’s Eastern Division, Huizenga went for broke in 1997. He brought in six new free agents, including star sluggers Bobby Bonilla and Moises Alou, and a solid starting pitcher in Alex Fernandez. He anted up for All-Star slugger Gary Sheffield—coming off a monster season for the Marlins in 1996—making him one of baseball’s first $10 million-a-year ballplayers. Huizenga even spent big bucks to bring in a first-class manager in Jim Leyland, who was going from famine to feast after 11 years of dealing with tightwad budgets at Pittsburgh.

BTW: At $1.2 million, Leyland’s 1997 salary was higher than any player back at Pittsburgh except Al Martin.

Before his shopping spree was over, Huizenga had committed a whopping $89 million on his new and re-signed players, which translated to a 1997 payroll topping out at $53 million.

The money appeared well spent. The Marlins followed up a 26-5 spring training mark by posting their best regular season record yet of their young existence at 92-70. The addition of Alou and Bonilla paid critical dividends to an offense that otherwise sagged—especially from Sheffield, mired in a crippling slump before a partial revival late in the year. (Sheffield’s season-ending totals of 21 homers and 71 RBIs would be almost half of what he produced in 1996.) Fernandez led the team with 17 wins, but it was the lanky, surly Kevin Brown—with a 16-8 record—who scared opponents the most, leading the team with a 2.69 earned run average while throwing the majors’ only no-hitter of the year at San Francisco.

Huizenga’s millions might have bought eight wins in 12 regular season contests against the Braves, but not the NL East title. The Braves prevailed once again, finishing a healthy nine games ahead of Florida.

The Braves had many assets Huizenga did not. The team’s Hall-of-Fame pitching triumvirate of Greg Maddux (19-4, 2.20 ERA), Tom Glavine (14-7, 2.96) and John Smoltz (15-12, 3.02) was made into a quartet by ex-Pirate Danny Neagle, who led the NL with 20 wins against just five losses. Chipper Jones (.295 average, 21 home runs, 111 runs batted in) continued to develop into a big-time star at third base. Omnipotent center fielder Kenny Lofton, acquired in a blockbuster trade with Cleveland, looked to be the piece that would make the Braves invincible—though a groin injury, while not affecting a .333 batting average, slowed him down on the basepaths with just 27 steals in 47 attempts. And the Braves now lived out of their posh, new baseball-only home of Turner Field, whose spacious power alleys placed wide grins upon the faces of Atlanta’s pitchers and speedy outfielders.

BTW: Lofton, traded for David Justice and Marquis Grissom, had averaged 65 steals in 79 attempts over each of his previous five years at Cleveland.

The good news for the Marlins was that, despite finishing second behind the Braves, they were good enough to secure the NL wild card spot. The bad news was that Huizenga, it seemed, could care less.

Huizenga’s outlook on the Marlins’ future soured considerably at midseason, after local politicians refused to give him tax relief on Pro Player Stadium. His logic sensed that if he couldn’t be granted this small gift, what chance did he have of getting a new ballpark built for the Marlins? That was, after all, Huizenga’s core payoff for opening his checkbook. Pro Player Stadium was more of a football stadium than a ballpark, with bad sightlines for baseball and, most critically in tropically wet Miami, no roof—a definite minus for the Marlins, who put up with 30 rain delays in 1997 alone. For Huizenga, it was an issue that transcended wins and losses; faced with a staggering $30 million deficit from his spending frenzy and no optimism for a new ballpark, he announced in June that he was selling the Marlins to the highest bidder—whether that buyer was in South Florida or not. The mostly veteran Marlins roster shrugged at Huizenga’s posting of the “For Sale” sign and motored ahead into the postseason.

Initiated in 1994, the wild card had been criticized by those who raised Cain about its devaluing of baseball’s regular season and its pennant races, with the plausibility that a first-place team could be paired up in the postseason with Number Two from its own division—and risk losing all that it had earned over 162 games in a best-of-seven series. But if the idea of the League Championship Series was to showcase the league’s two best teams, then the wild card was given a skewed legitimacy in 1997; after Atlanta, Florida’s record was the NL’s second best in general, better than the two other divisional champions—the NL West-winning Giants, who the Marlins would sweep in the NLDS, and NL Central champion Houston, easily brushed aside as the Braves’ first-round victims.

The Marlins, clearly not by design, were doing everything they could to handicap themselves against the Braves at the NLCS. Moises Alou’s wrist and hamstring were both hurting. Bobby Bonilla, also hampered by a bad hamstring, caught the flu to boot. Charles Johnson, who had become the first catcher in major league history to go through an entire regular season without an error, committed two against the Braves. Jim Leyland’s planned rotation was thrown out the window when Kevin Brown developed a stomach virus and Alex Fernandez, after getting shelled in Game Two, was found to have a severely torn rotator cuff.

BTW: Fernandez would not pitch again until 1999; his career ended a year later.

With the series even at 2-2, the Marlins sent rookie Livan Hernandez to the mound in place of the ill Brown. Hernandez had earlier tied Whitey Ford’s record by winning his first nine decisions, yet some wondered if he could handle the pressure of pitching a vital NLCS game. To Hernandez, this was nothing; real pressure was sprinting past Cuban authorities in Mexico City and defecting to America, leaving his entire family behind in Castro’s Cuba—as he did two years earlier.

Hernandez, who had pitched a few innings two nights earlier, went the distance, throwing 143 pitches and striking out 15 Braves to outduel Greg Maddux and win Game Five, 2-1. Brown, back in good health for Game Six, followed up Hernandez with 140 pitches of his own and finished the Marlins’ NLCS upset with a 7-4 complete game win over the Braves.

While critics bemoaned the wild card concept and denounced the Marlins’ entry into the World Series, an arguably less deserving opponent awaited them: The Cleveland Indians, owners of the worst record among four American League postseason combatants.

Loaded with offense and revenue but saddled with an ineffective pitching staff that had the majors’ ninth-worst team ERA, the Indians were practically awarded the AL Central title by default. They easily outpaced three divisional rivals (Kansas City, Minnesota and Detroit) in financial retreat, and a fourth (the Chicago White Sox) that strangely packed it in when, trailing the Indians by just three games with two full months to play, traded away a large chunk of their veteran talent in a highly premature display of surrender.

BTW: The Indians’ offense did an offseason makeover, losing signature stars Albert Belle and Kenny Lofton but adding David Justice, Marquis Grissom and Matt Williams; home-grown Indians in Jim Thome and Manny Ramirez reached maturity while Brian Giles wasn’t far behind.

Some may have felt that 86-75 was too cheap a record to qualify for October baseball, but as far as the Indians were concerned, karma was in order; it was their time to be spoilers a year after being upset as the #1 seed. Fair was fair.

Cleveland’s postseason odyssey began at the ALDS against the defending champion New York Yankees, who like the Marlins represented the wild card despite having the AL’s second-best overall record. But the Yankees lacked Florida’s destiny (to say nothing of their own from the year before) and were ousted by the Tribe in five, the Indians coming from behind at Cleveland to win the final two games—each by a single run.

Next on the Indians’ food chain of revenge were the Baltimore Orioles—the team who, as AL wild card the year before, had upset the top-dog Indians.

The tables were now turned. Despite a .193 series batting average, Cleveland continued its razor-thin success in the ALCS against the Orioles, owners of the AL’s best record at 98-64. In a six-game triumph, all four Indians wins were decided by a run each; they won Game Three in the 12th inning, Game Four in the ninth, and took the 1-0 Game Six clincher at Baltimore in the 11th courtesy of second baseman Tony Fernandez’s solo home run.

Skill, Clutch…and Luck

The Indians relied on one- and two-run victories—sometimes needing more than nine innings—to win each of their first two postseason series against the Yankees and Orioles. Here’s how they pulled out each playoff conquest on the road to their second AL pennant in three years.

If the Indians and Marlins used the World Series to prove they belonged as baseball’s best, they failed to persuade. It was an animated yet sloppy series that went the distance and then some, with a few calling it the ugliest seven-game set since the Chicago Cubs and Detroit Tigers went at it in 1945 with rosters full of wartime retreads. Games went on forever. Awful pitching was represented with 76 total walks (a Series record), 45 pitching changes and a combined 5.08 ERA. Thirteen errors were committed. TV ratings were dismal, and NBC President Don Ohlmeyer publicly prayed that the series would be done in the minimum four games so a fifth wouldn’t cancel out the network’s “Must-See TV” Thursday night lineup of Seinfeld, Friends and ER.

One major, unexpected bright spot amid all the misfiring on the mound came from two young Cleveland pitchers: Chad Ogea, who twice in the series outdueled Kevin Brown, and 21-year-old Jaret Wright, who allowed two hits through six-plus innings of Game Seven and left with a 2-1 lead. But neither the Indians’ bullpen nor their defense could hold. The Marlins tied it in the ninth on a sacrifice fly by Craig Counsell—who, batting again in the 11th, bounced what appeared to be an inning-ending double play to Tony Fernandez. The veteran second baseman, whose home run won the ALCS, was now about to help lose the World Series as his attempted pick-up of the ball tipped off the top of his glove and into right field, deeply enhancing Florida’s threat.

Three batters later, with two outs and the bases loaded, Marlins second baseman Edgar Renteria—the only active Colombian native in the majors—knocked a high-hopper up the middle, glancing off the top of pitcher Charles Nagy’s glove and dancing between the desperate slides of Cleveland middle infielders, bringing an ecstatic Counsell home from third to win the Marlins their all-but-paid-for world championship.

For the Marlins, it was a World Series triumph in just their fifth year of existence. For the Indians, on the eve of their 50th anniversary since their last championship, they’d have to patiently extend the wait.

A hero in the ALCS, Cleveland’s Tony Fernandez becomes the World Series goat when he’s unable to handle Craig Counsell’s playable grounder that opens the door for Florida’s Series-winning rally in the 11th inning. (Associated Press)

Wayne Huizenga got his World Series trophy, but he didn’t get his new ballpark. And that’s what he wanted more; such priority was on the record with the local press. As quickly as he said “Congratulations,” Huizenga coldly began dissembling what he had assembled, littering the major league landscape with ex-Marlins. Traded or released were Kevin Brown (San Diego), Moises Alou (Houston), closer Robb Nen (San Francisco), Al Leiter and reliever Dennis Cook (New York Mets), and original Marlins Jeff Conine and Alex Arias. Early in 1998, Huizenga completed his clearance sale with a monster trade that sent five players, including Gary Sheffield, Bobby Bonilla, Charles Johnson and Jim Eisenreich, to Los Angeles for Mike Piazza and Todd Zeile. Just so Piazza and Zeile knew how the others felt, they too would become ex-Marlins—Piazza, within a week, to the Mets, and Zeile to Texas after the All-Star break.

By the end of 1998, only Edgar Renteria and Livan Hernandez remained as starters from 1997. The Marlins’ money tree had been hacked to its stump with a $16 million payroll—not even a third of what it had been a year earlier. The new and unproven Marlins began 1998 with an Opening Day victory and then lost a franchise-record 11 straight, on their way to the majors’ worst record at 54-108. Manager Jim Leyland, who had been lured to Florida on the basis he’d be handed a big budget, was suddenly back in the bare-bones environment he’d escaped from at Pittsburgh. Leyland stuck it out for 1998, but that was all he could take; using a provision in his contract, he fled to Colorado.

Wish You Were Here

As the Marlins crashed their way back to Earth with a 54-108 record in 1998, the performances of ex-Marlins playing elsewhere paints a picture as to how playoff-worthy Florida might have been had the team not been broken up.

In baseball, as with everything else, you usually get what you pay for. Wayne Huizenga played day trader and struck it rich, but while money bought the Marlins a World Series, it certainly did not buy happiness. For South Floridians, their open-and-shut championship would ultimately serve as an emotionally empty experience.

Forward to 1998: The Maris Sweepstakes Mark McGwire and Sammy Sosa embark on a historic record-breaking pursuit of Roger Maris’ long-standing season home run mark.

Forward to 1998: The Maris Sweepstakes Mark McGwire and Sammy Sosa embark on a historic record-breaking pursuit of Roger Maris’ long-standing season home run mark.

Back to 1996: Here’s Spittin’ at You, Kid Roberto Alomar takes center stage in the worst way, only to have it stolen by a Jersey kid in a classic case of poetic justice.

Back to 1996: Here’s Spittin’ at You, Kid Roberto Alomar takes center stage in the worst way, only to have it stolen by a Jersey kid in a classic case of poetic justice.

1997 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1997 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

1997 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1997 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

The 1990s: To Hell and Back Relations between players and owners continue to deteriorate, bottoming out with a devastating mid-decade strike—souring relations with fans who, in some cases, turn their backs on the game for good. Recovery is made possible thanks to a series of popular record-breaking achievements by ‘class act’ stars.

The 1990s: To Hell and Back Relations between players and owners continue to deteriorate, bottoming out with a devastating mid-decade strike—souring relations with fans who, in some cases, turn their backs on the game for good. Recovery is made possible thanks to a series of popular record-breaking achievements by ‘class act’ stars.