THE YEARLY READER

2020: Pandemicmonium

Baseball endures the unexpected challenge of trying to wring out a season as a largely unchecked pandemic rages through America.

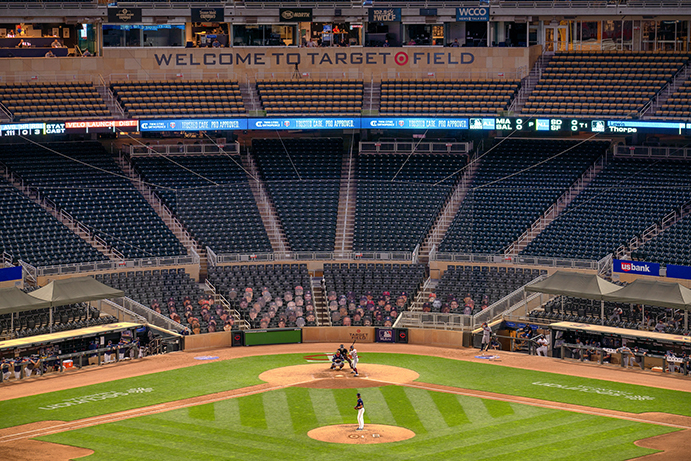

Quarantined baseball: The Minnesota Twins and Cleveland Indians face off on July 30 at Minneapolis’ Target Field before a sea of empty seats and a smattering of cardboard cutouts quietly posing as fans. This would be the scene at ballparks everywhere throughout the entirety of a shortened MLB season. (Flickr—Chad Davis)

The Los Angeles Dodgers were so close to their first world title in 32 years, they could smell it. Here they were, in Game Six of the World Series, holding on to a tight seventh-inning lead over the budget-defying Tampa Bay Rays. With a strong bullpen and a lineup virtually lacking any weakness, the Dodgers felt confident about their prospects.

Up to that moment, Commissioner Rob Manfred could also smell the successful end to a challenging season, displaying neutral prejudice within a neutral site, simply wishing for the best team to win. But then he received a note: Justin Turner, the Dodgers’ star third baseman and clubhouse leader, had tested positive for COVID-19, the virus that had crippled the baseball season, the greater U.S. economy and, at that moment, had caused the deaths of over 200,000 Americans with no end in sight.

Suddenly, Manfred found himself a rooting interest—whether he wanted to admit it or not. A positive test meant the possibility of mass infection that could indefinitely shut down the World Series. A Tampa Bay comeback meant a Game Seven that could be delayed a day, a week, maybe longer. Thus, all Manfred probably wanted at this point was to get the season done; in his mind, it was root, root, root for the Dodgers.

Historically, baseball managed to successfully survive through war, work stoppages, natural disasters and terrorism. But the COVID-19 pandemic, exacerbated in America by petty politics and poor leadership at the top, provided Major League Baseball with a challenge unlike anything it had previously experienced—and was not without its own missteps.

And to think that, at year’s beginning, the game was wrapped up in a major scandal that had nothing to do with plague.

Controversy began the previous November when Oakland pitcher Mike Fiers, who played for the 2017 world champion Houston Astros, claimed that the team cheated its way to the podium. The alleged scheme involved a video monitor, trash can and a massage gun to bang it with, tipping Astros hitters as to whether they’d get a fastball or off-speed pitch.

In response, MLB did its winter homework, interviewed those accused, and came up with a sensational conclusion: Fiers was right. The Astros had indeed cheated.

The wrath to follow would be crippling, widespread and full of fury.

MLB slapped the Astros with a maximum $5 million fine, stripped them of their first- and second-round draft picks for the next two years, and suspended general manager Jeff Luhnow and skipper A.J. Hinch—though the team did one better by immediately firing them.

Luhnow and Hinch weren’t the only casualties; the Boston Red Sox, also under investigation for using real-time video to cheat during their 2018 championship season, fired manager Alex Cora—a Houston bench coach in 2017—while eight-time All-Star Carlos Beltran, who played his last year for the 2017 Astros and was said to be one of the scheme’s ringleaders, was dismissed as manager by the New York Mets before he ever had a chance to pilot a game.

BTW: In April, MLB concluded that the Red Sox also engaged in cheating, but handed down a much lighter punishment—taking away a second-round draft pick while suspending the video room operator for a year.

Social media and 24/7 news/sports operations accelerated the rage. Specialty items highlighting the Astros’ cheating efforts became a cottage industry, with T-shirts, bumper stickers and coffee cups altering the Astros’ logo to include asterisks and trash cans. The Los Angeles City Council demanded that MLB strip the 2017 Astros and 2018 Red Sox—both of whom beat the Dodgers in the World Series—of their world titles. And pitcher Mike Bolsinger, released by the Toronto Blue Jays after getting shelled by Houston in a 2017 game in which the trash can was banging, sued the Astros for $31 million.

Players who benefitted from the plot were given immunity by MLB so they could spill their guts without fear of suspension. But the court of public opinion would be less kind. As spring camps opened and Astros players were no longer able to conveniently hide from the media, they gave lifeless apologies and ignorant shoulder shrugs. They knew what was coming: A full season of vocal retribution from angry fans practicing their booing, working up snide signage and collecting trash can lids to bang on at the ballpark.

Just as the Astros were loading up on earplugs and ready to face the gauntlet, along came something to save the day: A pandemic.

A coronavirus more contagious and deadly than the common flu had emerged in China months earlier and, by February, had reached the U.S. Initially, Americans displayed a false sense of security, given that previous worldwide epidemics had largely bypassed them. That’s because previous U.S. governments had done well to clamp down and prevent viral spread. By contrast, the administration of President Donald Trump fatally treated the arrival of COVID-19 with indifference, concerned more with its impact on Trump’s re-election prospects than with the wellbeing of the American people.

The seriousness of the virus reached a tipping point on the evening of March 11 when COVID-19 news broke on many fronts. The National Basketball Association announced it was shutting down its season effective immediately, the cities of Seattle and San Francisco announced attendance limits at events—even popular actor Tom Hanks had tested positive for the virus. The realization that COVID-19 was here to stay and would get worse—perhaps much, much worse—before it got better began a snowball effect over the next week, with more event cancellations, stay-at-home orders and mask mandates being implemented. America, essentially, was shut down.

Baseball was not immune to the outbreak. MLB canceled the rest of spring training and set back the start of the regular season two weeks to April 9. Then it was reset to mid-May. Then July, with time to prepare major leaguers through a second round of spring training.

No game today: The Chicago Cubs released this social media graphic that doubled as a public service message during the first months of the pandemic, as MLB owners and players heatedly debated the logistics of a belated, shortened campaign. (Chicago Cubs)

Along with the rescheduling of games—or just the salvation of any kind of season—came the complicated process of numerous logistics, from financial details to postseason play to health safety protocols. By the end of March, Commissioner Manfred, the owners and the players’ union appeared to agree on a big-picture platform that would include a shorter regular season schedule, an expanded postseason at possible neutral-site locations, and prorated player salaries strictly based on the number of games played.

The union thought it had a deal, but Manfred later denied anything as firm and final, calling the agreement a “starting point”—a likely back-peddling as owners began to understand the reality of just how much money they would lose with a shortened season played before little or no fans; some teams believed they would lose less money by not having a season at all.

From that backdrop, negotiations began between the two sides that proved to be the most contentious since baseball’s labor wars of the mid-1990s.

Owners were continuously persistent against prorated salaries. They first suggested a shortened season with players being paid exclusively from a revenue pool evenly split with the owners. When the union scoffed that away as a form of salary cap, the owners then tried a sliding-scale scheme where higher-priced players would receive a lower percentage of full salary than those on major league minimum wage. Then they proposed salary deferrals. Then a simple 25% reduction off prorated salaries.

The union shot down every suggestion. In turn, it lobbied the owners to play as many games as possible to increase maximization of wages based on prorated salary. That’s where it drew the line; the owners drew theirs in the max number of games considered fiscally acceptable under the union’s terms. That number, apparently, was capped at 60—and with time on their side, the owners simply ran the clock down in the negotiations’ back-and-forth until the players had no choice but to accept. But they never did; Manfred and the owners simply imposed the 60-game schedule, with properly prorated wages, at the risk of having the union file a grievance against them.

BTW: Who ended up being the highest-paid player in 2020? It was Prince Fielder, who earned $24 million—even though he hadn’t played a game since 2016 due to a career-ending neck injury. Fielder was still receiving money guaranteed in his contract from the Texas Rangers, wages not subject to any reduction in the shortened 2020 season.

Just convincing the players to return in the midst of a pandemic, with no vaccines to stop it, proved difficult. Some opted out of the shortened season, including star pitchers David Price, Marcus Stroman, Jordan Hicks, Ryan Zimmerman, Lorenzo Cain—and Buster Posey, who left San Francisco camp in July after admitting out loud, “What are we even doing here?”

Others shared Posey’s sentiment. Oakland reliever Jake Diekman pondered, “I feel like deep down, every player has it in the back of their mind that this is all going to fall apart.” Even Commissioner Manfred was skeptical, publicly stating at one point that MLB was going to be “lucky” to complete its season. (He later walked back the statement.)

Despite rigorous, almost daily testing, some players who decided to move forward with participation still got stricken with the virus. Before the rescheduled Opening Day, some 100 players (including reserves) tested positive, including a number of star players. Among them was Atlanta first baseman Freddie Freeman, who became so ill from COVID-19 that he literally thought he would die.

Meanwhile, in a Land Far, Far Away…

While an unprepared America was broadsided by COVID-19—forcing MLB into a greatly reduced, spectator-free season while the minor leagues were entirely shut down—baseball circuits in the Far East fared much better, in part because their governments were quick to act and contain the virus. The Chinese Professional Baseball League (CPBL) in Taiwan started a month late in mid-April, but got in its full 120-game schedule. So did the Korean Baseball Organization (KBO), whose 140-game season was delayed until May—with early games broadcast on ESPN for baseball-starved viewers back in America. In Japan, Nippon Professional Baseball (NPB) played a slightly shortened schedule of 120 games (down from the usual 140) beginning on June 19.

In terms of fans, the CPBL was again ahead of the game, allowing a maximum of 1,000 spectators per game in early May; by June, attendance was relaxed to 50% capacity. In July, the KBO and NPB began allowing fans back in, with various restrictions—among them the request not to root too loudly to prevent viral particles spreading more widely throughout the stands.

On July 23, the majors finally played ball again. But it certainly wasn’t going to look like anything before it.

Ballparks were empty except for photographers, a few front-office personnel and cardboard cutouts of fans, which varied in number from a handful to an entire field-level full at Philadelphia’s Citizens Bank Park; in the name of revenue, fans who wanted their likenesses placed upon the cutouts had to pay for the privilege. Teams also took advantage of extra income by upping ad visibility, placing sponsor logos and messaging on the back of the pitching mound, on tarps covering unused bleachers, and signs poking out amid the cardboard fans.

Traveling was treated with caution. The 60-game schedule was set up so teams could only play against others from the same geographic division in both leagues (i.e., West vs. West). Broadcasters could not work on the road, told instead to describe the video-fed action from their team’s home press box. And with the virus sealing off the U.S.-Canada border, the Toronto Blue Jays were left scrambling for a temporary American home to avoid playing against themselves in Canada, which had a far lower COVID-19 infection rate. The Blue Jays eventually settled on Buffalo’s Sahlen Field, the home of their Triple-A affiliate 60 miles from Toronto.

On the field, a few interim rule changes were incorporated to benefit the short, tight schedule. The designated hitter was used for the first time in the National League, allowing pitchers to purely concentrate on their craft. Infielders were asked to refrain from the tradition of throwing the ball around after each out to reduce the risk of potential transmission. But the most controversial change was the use of an automatic runner placed on second base to start every half-extra inning, a pet concept of Commissioner Manfred previously used in the minors. Though the auto runner was considered necessary to reduce the potential of marathon contests that could impact a team over a short season, it was widely assailed as a gimmick that devalued the purity of the game. It nevertheless seemed to curry favor with some managers, players and fans as the year went along, leading to suspicion that Manfred would move to make the rule permanent.

Before the truncated season’s first week was done, there was already trouble. Four members of the Miami Marlins, bar-hopping a week earlier in Atlanta amid the State of Georgia’s defiantly lax COVID-19 restrictions, tested positive for the virus. Within a couple of days, the number of infections within the team rose to 17. The outbreak set off a chain reaction of postponements affecting not only the Marlins but the Philadelphia Phillies—whose visiting clubhouse at Citizens Bank Park the Marlins were using—and all the teams they were scheduled to play over the next week.

Just a few days later, another outbreak hit the St. Louis Cardinals—knocking them out of action for a whopping 16 days. When everyone tested negative again and the all-clear was given to resume play, MLB had the daunting task of forcing the Cardinals to play 53 games over 44 days to keep the season on track. To overcome that hurdle, MLB had already come up with another unprecedented, 2020-induced wrinkle: Doubleheaders consisting of seven-inning games. The Cardinals would play 11 of 57 total such twinbills.

BTW: When allowed to play again on August 15, all 40 Cardinals players and coaches were each given a rental car to drive solo from St. Louis to Chicago to play the Cubs.

Best in Regular, Best in Post

The 2020 World Series was only the fourth such series pitting the teams with the best regular season records from each league since the 1995 introduction of wild cards participants. Below is the list of those four sets of teams that survived not just the marathon of the regular season, but the growing marathon of the postseason as well.

Remarkably, there was not a single verified positive test from a player in the season’s final four weeks, allowing MLB to start its postseason on schedule. And what a party it would be; in another pandemic-year twist, the number of teams would be upped from 10 to 16—over half of major league membership—adding a best-of-three “wild card” round involving all 16 teams. Despite the saturated free-for-all that the expanded postseason threatened to unleash, when all was said and done, the majors’ two best teams by the record—the Los Angeles Dodgers and Tampa Bay Rays—survived to the World Series.

Long season or short, the Dodgers entered 2020 as baseball’s overwhelming favorite to win it all, especially after making the opportunistic move to snare former AL MVP Mookie Betts from Boston and lock him up on a 12-year, $365 million contract. Neither Betts nor the Dodgers disappointed. Led by Betts’ agreeable numbers—a .292 average, 16 home runs, 39 runs batted in, 47 runs scored and 10 steals, respectively paced out to a 162-game season total of .292, 43, 105, 127 and 27—the Dodgers easily produced the majors’ best record (43-17), the most powerful offense (118 home runs, on pace to break Minnesota’s year-old mark) and the best pitching staff (3.02 earned run average).

The Dodgers sailed through the postseason’s first two rounds, sweeping both the overmatched Milwaukee Brewers—who, with the expanded playoff field, sneaked in with a 29-31 record—and the spunky San Diego Padres, starting to make noise with dynamic young shortstop Fernando Tatis Jr. and third baseman/former Dodgers rental Manny Machado. But the Dodgers nearly met an early demise in the NLCS, played at neutral-site Globe Life Field in Arlington before, for the first time all year, actual crowds capped at 25% of ballpark capacity. The NL East-winning Atlanta Braves, equally powered with potent bats, had Los Angeles on the ropes with a 3-1 series lead before Los Angeles fought back with three straight wins—winning the seventh game on late home runs from Betts and Cody Bellinger and a clamp-down relief effort from Julio Urias, perfect through the final three innings to secure a 4-3 win to match the series count.

Unlike the Dodgers, the Rays hardly emptied out the vault to forge their way to the World Series—because they didn’t have much money there to begin with. Burdened with the majors’ third lowest payroll, Tampa Bay spread its wealth of collective talent in proportional fashion, guided by savvy roster-making decisions and Microsoft Excel as analytics, not coaching instinct, ruled. This percentage-driven philosophy was underscored in that only two players on the Rays’ roster had enough plate appearances to qualify for the batting title, while no pitchers—not even former Cy Young Award winner Blake Snell and veteran Charlie Morton—accrued enough innings to rank in the ERA race, often pulled before the end of the sixth because the analytics insisted that fresh relievers would do better at that point. Beyond the spreadsheets, the Rays used discipline, solid defense and a strong bullpen to clean up with a 40-20 record that, by the percentages, was the best in franchise history.

Arozarenamania

The surprise star of the expanded 2020 postseason was Tampa Bay’s Randy Arozarena, the Cuban-born outfielder who played briefly for the St. Louis Cardinals before being traded to the Rays in January. Below are the explosive numbers produced by Arozarena—starting with a part-time existence in the regular season, followed by a record-setting postseason that included an unprecedented 10 playoff home runs.

Tampa Bay’s road to its second-ever AL pennant would not be easy. In the ALDS against the New York Yankees, it took a tie-breaking, eighth-inning home run in the winner-take-all Game Five from Michael Brosseau to move on. Brosseau’s blast, off of Yankees closer Aroldis Chapman, was as sweet as it was important; it served as payback for a September 1 dust-up between the two teams in which Chapman aimed a 100-MPH heater at the head of Brosseau—who thankfully ducked in time.

Awaiting the Rays in the ALCS: The Houston Astros.

Though spared the direct rage from fans still angered over their cheating episode as ballparks were shuttered from the general public, the Astros nevertheless struggled through the regular season, as top stars badly underperformed or fell to injury. Under 71-year-old manager Dusty Baker, brought in to restore dignity, Houston suffered in a weak AL West and finished a distant second to Oakland at 29-31. But because the expanded playoff format gave automatic access to all second-place teams, the Astros lucked in as one of two teams (along with the Brewers) to reach the postseason with a sub-.500 record. And then, as if to stick it to all the haters, the Astros woke up at the right moment. They shut down the AL Central-winning Minnesota Twins in a two-game, first-round sweep—then outmuscled the A’s, three games to one, in an ALDS held at a neutral-site Dodger Stadium that became unusually live in the autumn heat, yielding an all-time playoff series-record 24 home runs.

BTW: Neutral-site locations were used exclusively for the last three postseason rounds in Arlington (NLDS, NLCS and World Series), San Diego (ALDS and ALCS), Los Angeles (ALDS) and Houston (NLDS). Only the NLCS and World Series games in Arlington allowed fans, at 25% of capacity—or up to 11,500 per game.

The Astros appeared to run out of gas against the Rays in the ALCS, losing the first three games as Tampa Bay’s pitching proved far more resilient, while the Rays stumbled upon a potential star in 25-year-old Cuban native Randy Arozarena, who was setting rookie (and non-rookie) playoff records almost every day. Only the 2004 Red Sox had famously bounced back from a 3-0 hole to win a postseason series—in fact, they had been the only team to even come from 3-0 to set up a seventh game. But the Astros pulled it even, winning tight games with the help of solid pitching and pre-2020 hitting form for Jose Altuve and Carlos Correa, whose five home runs each against the A’s and Rays matched their entire regular season totals. In Game Seven, the Rays busted out to an early 3-0 lead on another Arozarena home run, while riding Charlie Morton for 5.2 shutout innings until the spreadsheet told him it was time to go. They hung on as a wobbly bullpen gave the Astros life toward the end—though not enough as the Rays prevailed, 4-2.

In a World Series pairing MLB’s two best teams to justify the shortened regular season before it, the ‘three outcomes’ ruled for much of the series, as 44% of every plate appearance ended in either a walk, strikeout or home run. Viewers at the ballpark or quarantined at home complained that they were just as much witnesses to the action as the fielders, watching hitters either walk to first, head back to the dugout in shame or slamming another deep drive over the heads. Which made the ending of Game Four all the more exciting and beautiful.

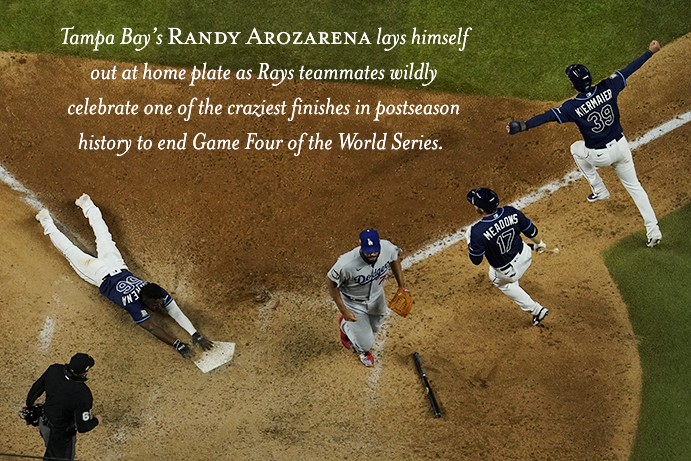

The Rays, desperate to avoid falling behind three games to one, trailed 7-6 with two outs in the bottom of the ninth and runners at first and second. Brett Phillips, primarily on the Tampa Bay roster for late-inning defense, was asked to bat because no one else was available. But the career .202 hitter managed to poke a soft liner that dropped in front of Dodgers center fielder Chris Taylor—who muffed the ball, glancing off to his left. Kevin Kiermeier, the runner on second, easily scored to tie the game; Randy Arozarena, busting his tail behind him, dared to score the game-winner—but tripped and fell between third and home, making him a dead duck. He next looked up and couldn’t believe what he saw: Catcher Will Smith, unaware that Arozarena had crashed, tried to grab Max Muncy’s relay throw to start a swipe tag, but it glanced off the side of his glove and rolled toward the backstop. Arozarena popped back up and scored the winning run, capping what some consider one of the most exciting finishes to any postseason game—with none of the three outcomes involved.

(Associated Press)

The Dodgers rebounded from the Game Four frenzy to cool off the Rays in Game Five behind ace Clayton Kershaw’s second series victory, but in Game Six they ran into a brick wall named Blake Snell, who was on fire for the Rays—allowing two hits with nine strikeouts and no walks through 5.1 innings. And then Tampa Bay manager Kevin Cash suddenly came out and removed him—because that was the analytical policy. Worse, Cash handed the ball to reliever Nate Anderson, who was riding a streak of six straight postseason appearances allowing at least a run.

Unfortunately for Anderson and the Rays, that streak would run to seven.

Mookie Betts doubled, putting runners at second and third; they would both score—one on a wild pitch, the other on a well-placed ground out. The Dodgers took a 2-1 lead and never looked back, adding an insurance run in the eighth while Julio Urias, as he did to close out the NLCS, retired everyone he faced over the final two-plus innings to lock down the Dodgers’ long-awaited return to the championship podium.

As the Dodgers celebrated on the field, Justin Turner was all but imprisoned underneath the stands, ordered not to return to the field as baseball’s first COVID-19-positive player in eight weeks. He escaped anyway, determined to be part of the fun. Sometimes without a mask, always without gloves, Turner held the World Series trophy and posed for a team photo. Rob Manfred, who had earlier left the field after the official presentations, was livid when told the news—but did not reprimand him for his actions. What the hell, Manfred thought, the season’s over anyway. No need to worry about delaying a Game Seven.

The season was indeed over, but the year continued. Over 2020’s final two months, the number of confirmed COVID-19 cases would double to 20 million, with an additional 100,000 dying of the virus. But two vaccines, and a new President, were on the way to try and get America back to normal.

And as for baseball? Who knew. Major league owners claimed they lost up to $3 billion in revenue. Players lost $2.5 billion in wages. The relationship between management and the union had badly eroded, with a new collective bargaining agreement to be hashed out in less than a year. MLB looked into the crystal ball for 2021 and saw only fog—unable to know if Opening Day would start on time, and/or if cardboard cutouts would still be the only ones allowed in.

A baseball official summed up the near future: “A million unknowns.”

Back to 2019: The Pill of Might Home run records fall like dominoes as skeptical fans, angry pitchers and an oblivious MLB grapple over if a juiced ball is to blame.

Back to 2019: The Pill of Might Home run records fall like dominoes as skeptical fans, angry pitchers and an oblivious MLB grapple over if a juiced ball is to blame.

Forward to 2021: Once Underachievers, Now Underdogs The Atlanta Braves, once so dominant yet unable to win Baseball’s big prize, performs a role reversal by ruining the championship ambitions of presumably stronger teams in the Dodgers and Astros.

Forward to 2021: Once Underachievers, Now Underdogs The Atlanta Braves, once so dominant yet unable to win Baseball’s big prize, performs a role reversal by ruining the championship ambitions of presumably stronger teams in the Dodgers and Astros.

2020 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 2020 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

2020 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 2020 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

The 2020s: The Turbulent Twenties Intended changes and unexpected disruption mark a time when Baseball attempts to appeal to a bigger audience, risking the loyalty of its most ardent followers. But an impressive influx of talented young players hopes to rescue the era and keep everyone happy.

The 2020s: The Turbulent Twenties Intended changes and unexpected disruption mark a time when Baseball attempts to appeal to a bigger audience, risking the loyalty of its most ardent followers. But an impressive influx of talented young players hopes to rescue the era and keep everyone happy.