THE YEARLY READER

2022: Houston Again, Honestly

Five years after cheating their way to their first World Series title, the Houston Astros return to baseball’s mountaintop—this time without fraudulence.

(Houston Astros)

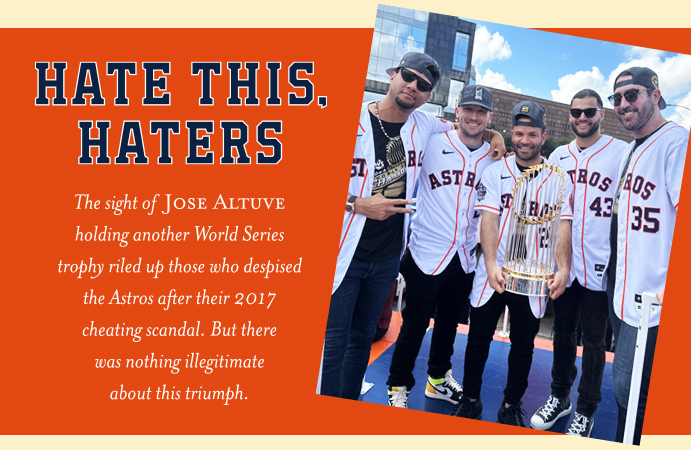

Ever since the cat was let out of the bag and the Houston Astros were exposed as having conned their way to the 2017 World Series podium, a subculture emerged within the society of baseball spouting a dogma of virulent anti-Astros hatred. Large in numbers, this group mockingly banged on trash cans, mercilessly booed the 2017 Astros’ prime suspects, and created a surge in the T-shirt industry with an endless supply of crude yet creative designs on the topic.

The Astros Haters were justified in their existence. The 2017 Astros had indeed cheated and got away with winning commissioner Rob Manfred’s “piece of metal;” once the scheme was revealed, their star players escaped punishment by turning state, providing crucial evidence in exchange for immunity. Worse for the Astros Haters, the team continued to win—although a second World Series triumph remained barely elusive.

For 2022, the Astros faced two major questions: Could shortstop Jeremy Pena, sporting no major league experience, possibly fill the shoes of Minnesota-bound All-Star Carlos Correa—and would ace pitcher Justin Verlander, virtually absent the previous two years with a series of injuries capped by Tommy John surgery, return to star form at age 39?

The Astros Haters salivated at the fantasy of an unraveling, aging Houston squad. But in the end, their animus would be matched with frustration— because the 2022 Astros were simply too good to cheat.

Before the season could begin, tension was developing over whether it would even be played.

After two years of the COVID-19 pandemic, the last thing baseball fans wanted to see was another disruption. But the Collective Bargaining Agreement between players and owners expired in December 2021, and Major League Baseball abruptly declared a lockout of its players; over a quarter-century of labor peace was at risk as the two sides began butting heads with more intensity than in recent memory. The players were definitely seeking a better environment, with good reason; over the previous six years, the average player salary dropped 6% while, more staggeringly, the median salary plunged by a whopping 30%. The owners’ strong-armed tactics in trying to forge a pandemic-affected 2020 season to their liking didn’t help the situation. While the owners did lose big money (as did the players) with games played at empty ballparks during the height of the pandemic, the estimated value of Major League Baseball franchises had not suffered.

Negotiations on a new CBA would not revolve around a single, crucially philosophical issue such as a salary cap—an outright clash which led to baseball’s last work stoppage in 1994-95, when the sport was brutally robbed of an entire postseason. This time around, there were multiple issues to discuss—but most of those were a matter of bringing contrasting numbers toward an acceptable middle ground. It didn’t seem so much a matter of whether an agreement could be made, but how fast it could be done.

With the ball in their court, the owners sat quiet for six full weeks before initiating in serious negotiations with the union—and once they did, talks were combative, with both sides publicly sniping at one another as Spring Training quickly approached. The owners, and Commissioner Manfred in particular, did themselves no favors on the P.R. circuit; Manfred smiled and chuckled at pressers while warning of imminent doom, called media criticism of him “tactical”—never mind that anti-MLB sentiment from fans on social media was far more biting—was caught on camera practicing golf swings during labor breaks, and generated eye rolls when he claimed that stock-market ROI outpaced that of MLB franchises.

As talks repeatedly broke down into March and Opening Day looked certain to be delayed, it was clear that MLB was not keen on compromise. “(Manfred) and the owners have been unable to build a functional relationship with the players, and are unapologetic about it,” wrote The Athletic’s Ken Rosenthal. “The owners wanted to win in another rout. Now everyone loses.”

Even when both sides finally came to an apparent agreement on March 9, MLB nearly scuttled the deal when it suddenly made a big stink over an international draft, a relative nothingburger during negotiations. If it was meant as a trial balloon to test the resolve of the union (to say nothing of public opinion), it quickly burst. The owners backed off, signed the agreement and barely saved a 162-game season—condensing the original schedule by a week with less off-days and more doubleheaders.

BTW: The approved Collective Bargaining Agreement included an expansion of the postseason from 10 teams to 12, permanent establishment of a universal designated hitter, a draft lottery in an attempt to deter tanking, a bonus pool for pre-arbitration players, and increases in both minimum salary and the luxury tax threshold.

With the lockout ended, the Astros Haters could go back to solely channeling their hatred on their least favorite ballclub. And they were feeling fairly satisfied when the Astros slumbered through April trying to slap themselves awake from the work stoppage. The wake-up call finally occurred in early May, when the Astros hit high gear and won 11 straight games—one short of the franchise record. The surge bolted them to the front of the American League’s Western Division ahead of the Los Angeles Angels (who imploded after a strong start, becoming a non-factor despite the presence of superstars Mike Trout and Shohei Ohtani) and the Seattle Mariners, who continued their gradual improvement thanks to the addition of twin rookie talents in flashy outfielder Julio Rodriguez and unyielding pitcher George Kirby.

The Mariners looked to make a big move on the Astros before the All-Star Break, forging a 14-game win streak—one shy of their team mark. That set the stage for their first series after the break, a potential statement-making, three-game home series against Houston.

There would, indeed, be a statement made—not by the Mariners, but the Astros, who swept Seattle and left no doubt about their status as kings of the AL West. They would take the division by 16 games with a 106-56 record under 73-year-old skipper Dusty Baker, hoping to overcome a snake-bitten postseason past.

So Close, and Yet…

Coming into the 2022 season, Dusty Baker experienced a level of constant postseason torture to rival that of Gene Mauch decades earlier. Here’s a list of key moments where Baker’s teams had series conquests within their grasps—only to let them slip away in heartbreaking fashion.

Offensively, the Astros were an efficient bundle of diversifying skills. Jeremy Pena aced the rookie test at shortstop, becoming one of five Houston players clubbing over 20 home runs (with 22); second baseman Jose Altuve, still shaking off the loudest boos from in-park Astros Haters, remained an excellent catalyst with a .300 bat average, 28 home runs, 103 runs scored and 18 stolen bases (in 19 attempts); and tall young outfielder Kyle Tucker added 30 jacks and a team-high 25 steals. But the most fearsome force in the Houston lineup was Yordan Alvarez, the imposing 25-year-old slugger from Cuba who over 135 games batted .306 and mashed 37 homers. His trademark power was on full display when he went deep—way deep—three times in a September game against Oakland; each round-tripper was registered at 430 or more feet, something few if any major leaguers had previously done while recording a hat trick.

As dynamic as the Houston offense was, its pitching was even better. There were no slackers to be found on the staff; its 2.90 earned run average was the AL’s best, and the bullpen’s 2.80 figure was the lowest seen in the league since 1981. Highlights included an unprecedented two immaculate innings (by Luis Garcia and Phil Maton) recorded in the same game on June 15 against Texas, and a no-hitter thrown 10 days later against a red-hot New York Yankees team (which entered the game with a 52-19 record), a combined effort from starter Cristian Javier, reliever Hector Neris and closer Ryan Pressly.

Above all of the above, Justin Verlander reclaimed his status as the main man in the Houston staff. Better than ever following his two-year layoff, Verlander garnered a 18-4 record, career-best 1.75 ERA and MLB-leading 0.83 WHIP (walks and hits allowed per inning). He was the no-doubt-about-it choice for the AL Cy Young Award, his third.

The Astros swept their way through the AL playoffs, though only one of their seven wins was by more than two runs. In a return engagement against the wild-card Mariners (making their first playoff appearance in 21 years), it took Houston 18 shutout innings and a Jeremy Pena solo homer to clinch the ALDS with a 1-0, Game Three win; next at the ALCS, the Astros outmuscled and swept the Yankees and Aaron Judge—who a month earlier was baseball’s center of attention with his successful pursuit of Roger Maris’ AL season home mark. Pena, again, wielded the hammer in the clincher—punching out a three-run homer in a 6-5, Game Four victory.

BTW: This was Houston’s sixth straight ALCS appearance, setting an American League record; the MLB mark remained that of the Atlanta Braves, with eight straight NLCS entries from 1991-99 (the postseason-less 1994 campaign omitted).

Discouraged by Houston’s unbeaten romp through the playoffs, the Astros Haters’ last hope rested on a third-place team led by a rookie manager.

The Philadelphia Phillies had been trying to recharge back to contender status for over a decade since their last playoff appearance. Even with a recent influx of star power that included slugger Bryce Harper, top catcher J.T. Realmuto and ace pitcher Zack Wheeler, a path back to October remained fleeting. For 2022, the Phillies added more muscle with outfielders Nick Castellanos and Kyle Schwarber, bulging up a payroll that would become MLB’s third biggest. Despite all of that and the presence of veteran manager Joe Girardi—owner of a World Series ring piloting the Yankees—the Phillies began the season scuffing along as usual; if a 22-29 start wasn’t bad enough, there were the sour optics of young third baseman Alec Bohm profanely spouting his hatred for Philadelphia during a three-error game, Castellanos engaging in a clubhouse confrontation with a Phillies beat writer and, for what it was worth, the team’s dubious honor of becoming the first in major league history to give up 100,000 runs.

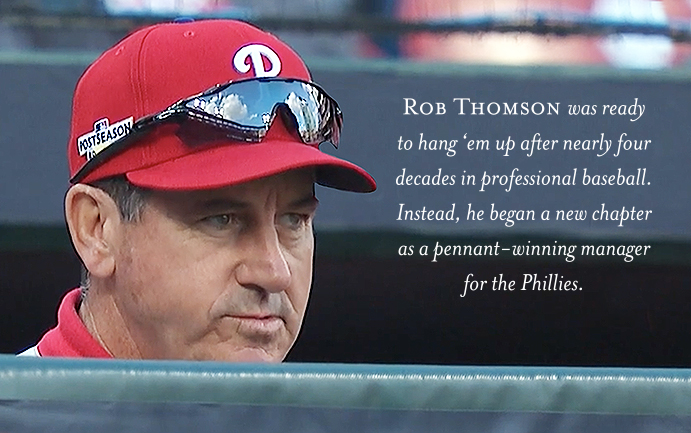

Phillies management had enough. They fired Girardi and replaced him with his former bench coach of 15 years, Rob Thomson—who months earlier had decided that the 2022 season would be his last in baseball.

Fate led to a change of plans.

Philadelphia won its first eight games under Thomson’s guidance—the second longest win streak for one starting his managerial career. But that early success was padded with well-timed luck, as two new baseball wrinkles would save the Phillies’ season. One was the designated hitter, newly cemented on a permanent basis in the National League; it allowed Harper, who couldn’t competitively throw but could hit without pain, to remain active with a bat. In 90 games as the DH, he hit .299 with 17 homers and 58 RBIs. The other fortuitous break for the Phillies was the expanded postseason; though the team finished a distant third in the NL East—well behind 100-game winners in the defending champion Atlanta Braves and talent-rich New York Mets—they grabbed the newly-created #6 seed, a third wild card spot, by a single game over Milwaukee.

Beyond Harper, there were key contributions from Schwarber, whose NL-leading 46 homers along with 86 walks—as a leadoff batter, no less—offset the lesser achievements of a .218 average and Phillies-record 200 strikeouts; and Realmuto provided a complete performance at the plate (.276 average, 22 homers, 84 RBIs), behind it with a well-deserved Gold Glove at the catcher spot, and on the basepaths with 21 steals in 22 attempts.

Once again, the Phillies proved the Wild Card Era adage that once you make it into October, all the won-loss records and stats from the previous 162 games don’t mean a damn thing. In the first Wild Card Series in which the lower seed had to play an entire best-of-three series on the road, the visiting Phillies quickly dismantled the NL Central-winning Cardinals at St. Louis in two games, ending the season for league MVP Paul Goldschmidt and the careers of retiring, Cooperstown-bound Albert Pujols and Yadier Molina. More impressively, the Phillies next took care of the Braves in the NLDS, three games to one, using well-placed and well-timed hits. Finally in the NLCS against the equally upstart San Diego Padres—who stunningly upset both the Mets and titanic (111-51) Los Angeles Dodgers in their first two series—the Phillies rolled to a four-games-to-one triumph, with Harper sealing the clincher with a come-from behind homer in the eighth inning.

BTW: For the NL playoffs, Harper batted .419 (18-for-43) with six doubles, five homers and 11 RBIs….The Phillies became the first third-place team to win a league pennant in a full season.

Justin Verlander and Dusty Baker desperately wanted to get some monkeys off their backs as the Astros readied to duel against the Phillies at the World Series. Verlander had never won any of seven previous Series starts, while Baker had failed in his two attempts as manager—while losing out eight other times, sometimes cruelly, just trying to get there. Alas for both, Game One would trigger a case of déjà screwed.

The Astros quickly built up a 5-0 lead before Verlander collapsed in the middle innings, unable to hold the advantage; both he and Baker could only watch as J.T. Realmuto’s 10th-inning homer proved the decider in a 6-5 Phillies victory. Philadelphia fans—and Astros Haters—rejoiced in the biggest come-from-behind World Series win since 2002, when Baker’s San Francisco Giants blew what would have been the series clincher against the Anaheim Angels.

Houston jumped out to another 5-0 lead in Game Two, a consequence that seemed almost as much a curse upon the Astros than the Phillies. This time, however, the Astros held behind steady, solid starter Framber Valdez, who helped keep the Phillies at bay with a 5-2 home win. The Phillies rebounded in Game Three at Philadelphia, taking the series lead with a 7-0 bombardment against Lance McCullers Jr.—who became the first pitcher ever to surrender five home runs in a postseason game. Down two games to one, the Astros found themselves climbing a steeper hill toward their first legitimate world title; Astros Haters grinned over Houston’s lengthening odds.

For Game Four, the Astros sent to the mound young right-hander Cristian Javier, whose flashes of brilliance throughout the season included his primary role in the team’s combined no-hitter over the Yankees back in June, and a current run of dominance in which, through 29.2 previous innings, he had allowed but a single run on eight hits with 36 strikeouts. Now he faced a potent Phillies offense feeling frisky of tilting the series more firmly in their favor.

To say that Javier met the challenge was an understatement.

For six innings and 97 pitches, the Phillies could muster a mere two walks off the 25-year-old Dominican, striking out nine times. In line with Baseball’s reduced threshold of pitches thrown by a starter at 100, the Astros pulled Javier and denied him a shot at eternal baseball glory. But they also knew that they could rely on a bullpen that had been lights out in the postseason—and they would not be disappointed as Bryan Abreu, Rafael Montero and Ryan Pressly each contributed a hitless inning to wrap up the second no-hitter in World Series history, following Don Larsen’s legendary 1956 gem.

BTW: The Astros became the first team to achieve two no-hitters using multiple pitchers in the same season; conversely, the Phillies became the first to lose two such games in one year, having been no-hit by five Mets pitchers on April 29.

With the series tied, the pressure fell back upon the shoulders of Justin Verlander for Game Five. In his ninth attempt to pick up World Series win #1, the old pro struggled through five stressful innings; he surrendered a home run to the very first batter he faced (Kyle Schwarber), loaded the bases in the second, and saw baserunners reach scoring position in two other frames. While Verlander bent like an India rubber man, he never broke; he barely survived intact, somehow allowing just the one run and departing with a 2-1 lead. From the dugout, Verlander watched anxiously as the Astros had to rely on an insurance run and several heart-stopping defensive moments—including center fielder Chas McCormick’s remarkable leaping catch against Citizens Bank Park’s cyclone fence in the ninth to deny Realmuto, and finally reward Verlander in a 3-2 victory.

Back in Houston, the Astros had two games to win one and the series. But they’d seen this movie before; in a similar scenario against the Washington Nationals three years earlier, the Astros lost both games. Dusty Baker was not managing Houston at the time, but he could surely relate to such pain given his track record of postseason heartbreak.

For five innings in Game Six, Framber Valdez exchanged zeroes with the Phillies’ Zack Wheeler—but in the sixth, Valdez blinked first as Schwarber broke the ice with another solo homer, his sixth of the postseason. Given a 1-0 lead, Wheeler started his half of the sixth by plunking catcher Martin Maldonado—who was practically standing over the plate—and then after getting Jose Altuve to hit into a force, was removed by Rob Thomson in a purely analytics-driven move that immediately recalled the controversial hook Tampa Bay manager Kevin Cash gave Blake Snell two years earlier, in another pivotal World Series moment.

As Cash’s tactic backfired then, so did Thomson’s. Phillies reliever Jose Alvarado was brought in to face Yordan Alvarez because, lefty on lefty. It didn’t work in a critical moment in Game Four—when Alvarado hit Alvarez with his first pitch, sparking a five-run Astros rally—and it surely didn’t work now as the Houston boomer cracked Alvarado’s fourth pitch 450 feet, over the center-field wall and over the tall grassy batter’s eye into the laps of delirious fans within a series of hi-rise drinking rails at Minute Maid Park. It gave the Astros the lead for keeps; they notched an insurance run and prevailed to win the game, 4-1—and the series, four games to two.

BTW: Wheeler, when asked about the sixth-inning hook: “It caught me off guard a little bit.”

Alvarez was among Houston’s postseason stars, launching three homers—all of them go-ahead blasts in clutch moments. Jeremy Pena, who like Alvarez wasn’t around in 2017 to take advantage of banging trash cans, finished a terrific playoff season with a .345 average and four homers, winning both the ALCS and World Series MVPs. Backing them up was a stout Houston bullpen that over 54.1 postseason innings compiled a 0.83 ERA, .126 opposing batting average and no blown saves.

Foiled again, the Astros Haters struggled to find conspiracy to chew on. They called out Framber Valdez for doctoring the baseball—but Rob Thomson shrugged, saying that the umpires checked Valdez repeatedly and found nothing. They accused Maldonado of using an illegal bat, which was technically true but far from nefarious; borrowed from the Cardinals’ Albert Pujols, the bat—which had a thicker barrel and was more prone to shattering—was banned in 2010 for use by ballplayers, except those who’d been using it beforehand. Pujols was thus grandfathered; Maldonado, who joined the majors in 2011, wasn’t. It was an honest mistake from a ballplayer who had three singles in 15 World Series at-bats.

If there was to be any controversy in the wake of Houston’s first ‘on-the-level’ championship, it would be found within the Astros’ front offices. General manager James Click, who succeeded the disgraced Jeff Luhnow after the 2017 cheating scandal broke early in 2020, was pushed out in what was said to be a power move by owner Jim Crane, seeking more control over player moves. Additionally, an ESPN report cited a toxic environment in which even Hall-of-Fame advisers—former star players who typically chill amongst employees for easy money—were yelling at the staff.

Once upon the time, the Astros cheated, won because of it, and got away with it before being exposed. They paid their price, reshuffled and prevailed the honest way, even if turbulently so. They moved on.

Maybe it was time for the Astros Haters to do the same.

Back to 2021: Once Underachievers, Now Underdogs The Atlanta Braves, once so dominant yet unable to win Baseball’s big prize, performs a role reversal by ruining the championship ambitions of presumably stronger teams in the Dodgers and Astros.

Back to 2021: Once Underachievers, Now Underdogs The Atlanta Braves, once so dominant yet unable to win Baseball’s big prize, performs a role reversal by ruining the championship ambitions of presumably stronger teams in the Dodgers and Astros.

Forward to 2023: Get Them Home by Ten New rules intended to speed up the game and increase offense lead to one of Baseball’s most transformative seasons—and ends with the wild-card Texas Rangers conquering the first world title in their 63-year history.

Forward to 2023: Get Them Home by Ten New rules intended to speed up the game and increase offense lead to one of Baseball’s most transformative seasons—and ends with the wild-card Texas Rangers conquering the first world title in their 63-year history.

2022 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 2022 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

2022 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 2022 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

The 2020s: The Turbulent Twenties Intended changes and unexpected disruption mark a time when Baseball attempts to appeal to a bigger audience, risking the loyalty of its most ardent followers. But an impressive influx of talented young players hopes to rescue the era and keep everyone happy.

The 2020s: The Turbulent Twenties Intended changes and unexpected disruption mark a time when Baseball attempts to appeal to a bigger audience, risking the loyalty of its most ardent followers. But an impressive influx of talented young players hopes to rescue the era and keep everyone happy.