The Ballparks

Candlestick Park

San Francisco, California

(Interactive Resources)

Mark Twain said that the coldest winter he ever spent was summer in San Francisco. It’s quite possible that he spent it at Candlestick Point, which years later would beget Candlestick Park—a windswept tundra where fans and players alike held on to their hats, parkas and hot chocolate as they struggled to enjoy the summer game in Arctic-like conditions and exclaimed “vinim, vidi, vixi” before thawing out.

It’s late May, 1986 in San Francisco. Everywhere else in the Bay Area, it’s a comfortable 70 degrees or more at sunset. But not at Candlestick Park.

So this writer is prepared. Along with most of the other 29,000 fans in attendance for a Giants game, I know what’s coming: The chilly marine air accompanied by the icy, unrelenting winds that seem imported straight from Alaska. Seated halfway up the top level along the right-field line, I’m wearing a thick wool sweater my father bought me when he was traveling through St. Andrews in Scotland—a place which, like Candlestick, is known for its blustery, biting summer weather. If the sweater’s warm enough for St. Andrews, it’s got to be warm enough anywhere. But not at Candlestick Park.

Stay warm, I tell myself. Concentrate on the game. Think about Hawaii in between innings. Drink something warm—that’s it, find a vendor carting hot chocolate for sale. Unfortunately, everyone else is thinking the same thing. After all, I’m not the only one with one eye on the game and the other on the next hot chocolate vendor to emerge from the concourse. Because when he does come out, he’s instantly mobbed like a pop star helplessly descended upon by teenage girls. So I have to consider making the long walk myself to the concession stand and hope that there’s hot chocolate left to sell. Anyplace else, that walk would be easy—so long as your knee joints aren’t frozen by the Arctic wind gusts. But not at Candlestick Park.

Visitors who came straight to San Francisco and, by glacial extension, Candlestick Park often needed a lesson in Bay Area microclimates. It’s rather remarkable; on a summer evening at Candlestick, it could feel as cold as Green Bay’s Lambeau Field in January—and yet, at the same moment just 30 miles to the east in Livermore Valley, residents kept the AC blasting while temperatures dangled near 100 outside.

Howard Cosell didn’t heed the lesson. During the 1984 All-Star Game at Candlestick, the grandiose-talking Cosell started bitching on air about the wintry conditions in the ABC TV booth. Al Michaels, his play-by-play partner who once did broadcasting for the Giants and understood the local atmospherics, tried to convince Cosell that while they were shivering, people some 10 miles down the peninsula were comfortably barbecuing outside in short-sleeve shirts and shorts. Cosell didn’t buy it. He went on with the bitching. Michaels kept trying to sell him. “Howard, I’m telling you,” he continued with a rich grin only a local could needle an Easterner with, “right now, they’re kicking back in their backyards and enjoying the warmth.”

As memorable as that exchange was, Michaels and Candlestick will forever be intertwined in history for the moment five years later—just minutes before the Giants were set to host their first World Series game since 1962—that he interrupted Tim McCarver’s pregame analysis in a rolling press box and blurted out “I’ll tell you what, I think we’re having an earth…” before the ABC feed alarmingly cut to static. An earthquake registering 7.1 on the Richter scale, centered 40 miles to the south, battered the Bay Area and killed 67 people. Candlestick swayed and cracked, the upper deck and light standards dancing with one another while 60,000 nervous fans feared for their lives. But the structure held; not one person was hurt.

And so it was on that unusually warm and still evening, October 17, 1989, that Candlestick Park emerged as a hero. But for the rest of its 45-year existence, the wind-swept ballpark turned swirling, multi-purpose monstrosity was vilified by everyone who stepped foot in it. Weather, undoubtedly, was the primary reason. Giants fans, in particular, held a true love-hate affair for the venue, with a heavy slant on hate. Candlestick Park was a cold, grim, concrete slab—but it was their cold, grim, concrete slab.

“Get Off the Dime.”

Baseball in San Francisco was hardly a novelty before the Giants’ arrival in 1958. In 1903, the newborn Seals became an inaugural member of the Pacific Coast League, playing in early ramshackles as Central Park, Recreation Field and Ewing Field before upgrading in 1931 to 18,000-seat Seals Stadium—where the team entered its most romantic period as native San Franciscans Joe DiMaggio, Lefty O’Doul and Frankie Crosetti plied the local trade. Based south of downtown near where Interstate 80 and Highway 101 currently meet, the steel-and-concrete Seals Stadium didn’t quite have the problems of their wooden ancestors, and dealt with less wind; in 1946, the Seals drew 670,000 fans—setting a minor league record that would stand for 36 years, while outdrawing two major league teams (the Philadelphia Athletics and the St. Louis Browns) that same season.

The Seals’ success, combined with the successful debut of pro football’s 49ers in the late 1940s, enticed San Francisco politicians to dream of bringing a major league ballclub to town in the near future. In 1954, a year after city supervisor Francis McCarty told his colleagues that it was time to “get off the dime” and act, his colleagues took his advice and placed an initiative in which $5 million would be set aside to build a new ballpark—provided that a major league team came to San Francisco within five years. Residents cleared the two-thirds threshold needed for approval, with 70% saying yes.

With the ballpark initiative doubling as an invitation for major league teams, San Francisco became a frequent topic of conversation on the relocation rumor mill. A number of second-class teams—the aforementioned A’s and Browns among them—were said to inquire about a move to San Francisco, but New York Yankees owner Del Webb told the San Francisco Examiner to hold out for someone better. “To me, it makes more sense to buy a successful club or business,” Webb said. “Then you have something. Say for instance, the New York Giants…I’m not saying they are for sale or ever will be. I’m merely using them as an example.”

Webb’s words served as a possible dog whistle to Horace Stoneham. The Giants’ owner, whose thick-rimmed glasses and squat, nebbish appearance made him look like a finalist in the Truman Capote look-a-like competition, was squirming over the team’s state of affairs at the Polo Grounds, a deteriorating ballpark in a deteriorating—and increasingly dangerous—section of New York City. Team attendance was sinking despite a formidable roster fronted by five-tool wonderkid Willie Mays. Stoneham had been eyeing a move to Minneapolis, home of the Giants’ top minor league affiliate, but San Francisco intrigued him. He told city reps that he’d seriously consider relocating to the Golden Gate—but they’d have to double their financial commitment for a new ballpark to $10 million.

Oh no, thought San Francisco mayor George Christopher, who was now the civic lead on the ballpark effort. He brooded over the thought of asking voters for another $5 million, so he created a non-profit thing called Stadium Inc., which had a board of members but otherwise nothing tangible such as office space. It was basically a facade to quietly sneak more dollars toward a ballpark through various channels of city government without the voters getting involved.

Initially, the favored site for a new ballpark centered around spacious McLaren Park, buried away in city neighborhoods about a mile west of where Candlestick Park would be placed. But nothing was locked in stone. Some considered expanding Seals Stadium—but parking, a growing essential as private car ownership exploded, was nonexistent while an engineering study declared that the existing lower bowl couldn’t support a second level. Other city hotshots had an even more ambitious thought: A downtown ballpark. Planners behind that movement considered the plot of land where the Moscone Convention Center would later be built, just south of bustling Market Street—all within easy reach of hotels and restaurants that could generate abundant private and public revenue. It was an idea ahead of its time, and thus the future was a fog for retail merchants—and even some restaurateurs—who feared a loss of customers they assumed wouldn’t want to compete with ballpark-fueled congestion.

That left an isolated outlet of land alongside a lonely, barren hill on the southeast edge of the city as the sole remaining option. Depending on what history book you read, Candlestick Point is named either after a migratory bird that visits the area or a formation of rocks that appeared like candlesticks to San Francisco Bay boaters. In 1953, 41 acres of Candlestick Point was purchased by Charles Harney, a construction owner who planned to use the site for industrial purposes. And whaddayaknow, Harney and two of his employees just happened to be on the Stadium Inc. board—which decided not only to approve Candlestick Point as the place where the ballpark would be built, but to allow Harney himself to build it without sweating through a bid process. It gets even juicier; the city made Harney an instant millionaire by purchasing the ballpark land he owned at $66,000 per acre—30 times what he had bought it for. All of this, while adjacent land was scooped up for only $6,500 an acre. One had to wonder if all the dirt Harney had been scooping up over the years included that of city officials to pocket that exorbitant amount of dough.

A grand jury would later look into the shenanigans and reveal that Stadium Inc.’s backdoor maneuvers, along with giveaways to the Giants such as local TV rights, would saddle San Francisco with over $500,000 in annual debt. The major city newspapers, buddy-buddy with City Hall when it came to kissing the Giants’ feet, all but buried the story—but not another one in which Mayor Christopher labeled Henry North, the relentless foreman of the grand jury and a bigwig within local social circles, as an “incoherent” drunk. North sued Christopher for libel, but by this time he’d lost most of his friends who’d sided with the mayor.

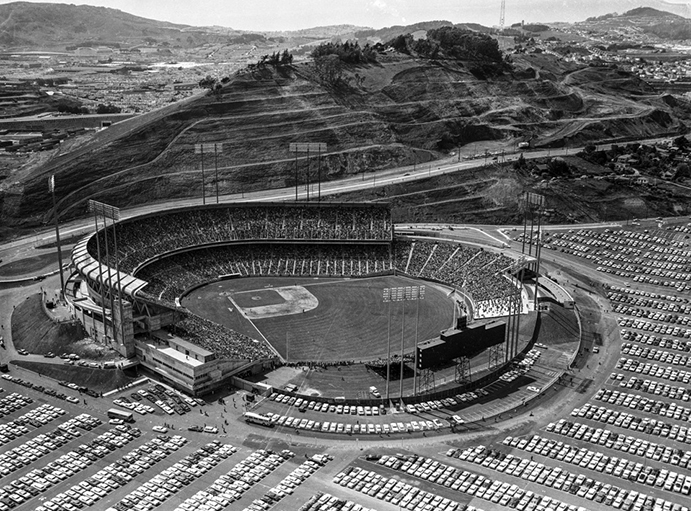

Candlestick Park, in its original layout for its very first game in 1960. Winds routinely accelerated around adjacent Bayview Hill and gusted straight in from left field. (OpenHistory.org)

Concrete Thinking.

Designing the new ballpark would be John Bolles, born, raised, educated and based in the Bay Area. Among his works were (and would be) the first iteration of Caesars Palace in Las Vegas, an IBM facility that would be among the first Silicon Valley-centric to be built, the elegant Paul Masson Winery near San Jose, and most every Macys store in Northern California. Bolles’ default style was one of minimalist modernism with a touch of the Jetsons.

Candlestick Park would be something of a departure for Bolles; from the outside, the upper portion of the structure would be its most distinctive with a curved concrete fold, supported by a repeating series of diagonal steel beams. Below, the upper rhythm would be shattered by a potpourri of ramps, slatted walls, yellow service doors and protruding entry areas.

From the inside, Candlestick would have a more laid-back feel, with the field level stretching from the right-field foul pole to behind left field, while an upper deck mothering a mezzanine/press level would have a shorter wrap from first base to the left-field pole. Behind right field, three makeshift bleachers worthy of high school football would be casually spaced from one another, sitting almost adrift in a spacious concrete-surfaced block in front of the 164×90-foot main scoreboard—which, at the time of the park’s 1960 opening, would be the majors’ largest. Color seemed a forgotten notion; outside of the seven tall light standards being coated in Golden Gate red, there was almost none to speak of. The ballpark would be built entirely of reinforced concrete—a first among major league venues—and it definitely showed with its natural gray surface untouched by few if any strokes of paint.

Dearth, Wind and Ire.

Bolles boasted that Candlestick would be “without any question…the finest stadium in the world.” This, even after he had to compromise on some details due mostly to budget. The curved concrete overhang atop the upper deck was originally drawn up to cover more of the fans to protect them from the elements, while the upper level originally was planned to wrap around the left-field foul pole in unison with the lower bowl below. By not doing the latter, Candlestick opened itself up to vicious headwinds curling around adjacent Bayview Hill.

One would think that Candlestick Point’s location, set bayside at the southeastern edge of San Francisco—and thus as far away from the blustery Golden Gate isthmus as any other point in the city—would be a enclave of relative warmth. But a quick weather lesson is in order to understand why it’s instead so bastardly blustery. It starts with cold winds generated from Pacific waters, the temperatures of which are always stuck in the 50s. From the city’s west-side beaches, a jet stream funnels the icy winds in a southeasterly direction through the Alemany Gap, an expanded lowland portion of San Francisco, without much vertical interference until it reaches Bayview Hill—with Candlestick Park on the other side. But the 500-foot alp is not a protectant; it actually makes things worse, because it compresses the wind and accelerates it around the hill—right into the ballpark. The result is a bone-chilling zephyr that leaves visitors about as uncomfortable as could be, lest they bring their thermal underwater and heating oil to rub on their skin—as some players eventually would do.

The natives knew about all of this, which is why they made damn sure that Horace Stoneham would get his first look at Candlestick Park in mid-morning—before the winds kicked up. But they apparently weren’t keeping track of Charles “Chub” Feeney, Stoneham’s general manager, when he came alone to Candlestick during construction—and during the afternoon. With the winds howling, a concerned Feeney asked a nearby construction worker, “Is it always windy here?” “No,” replied the worker, “just between one and five in the afternoon.” An ashen Feeney almost fell to the ground—and not because of the wind. “But that’s when we play our games!” he cried out.

The Giants transferred to San Francisco for the 1958 season knowing they were going to have to play a season at old Seals Stadium—and despite its minimal (22,900) capacity, they drew 1.27 million fans, nearly double the total of their last year at New York. The team was expecting Candlestick Park to be ready for Opening Day 1959, but that date got pushed back to July 1, then October—assuming the Giants would reach the World Series, which they were on target to do until blowing a two-game lead with a week-plus to play.

One thing after another pushed back construction. A Teamsters strike delayed the installation of seats; the San Francisco Fire Department forced John Bolles back to the drawing table to add one more exit ramp and water lines after declaring Candlestick a “fire trap”; and the city had to replace the entire playing field after the Giants found it unacceptable, with sprinkler heads positioned above the grass. There was genuine concern that the new park wouldn’t even be ready for the start of the 1960 season—with Seals Stadium, already demolished, no longer a fallback.

But the real problem was Charles Harney. Serving on the Stadium Inc. board allowed Candlestick Park’s builder to be an opportunist; he had now become a jerk to boot. Harney was enraged that the ballpark wouldn’t be named after him—the city decided to let the public vote, with Candlestick Park the most popular among 20,000 entries—and so the man whose reputation for expedient construction earned him the nickname “Hurry-up Harney” went into stall mode. He spent more time feuding than building, clashing with the city over extra work orders that he claimed he was being billed for; with John Bolles over late design changes; and even with the Giants—who were trying to establish office space, clubhouse and posh Stadium Club details. When team officials attempted to enter the ballpark, they were met—and denied—by armed guards hired by Harney.

Piping Cold—and Deep, Too.

Cooler heads prevailed and, finally in April 1960, Candlestick Park was ready to play ball. Its 43,765-seat capacity was filled on Opening Day, as the Giants defeated the St. Louis Cardinals by a 3-1 margin. Among the dignitaries present was Blanche McGraw, the widow of legendary New York Giants manager John McGraw, and Vice President Richard Nixon. “This will be one of the most beautiful baseball parks of all time,” Nixon said, a statement about as believable as “I am not a crook.”

There were all sorts of issues that needed ironing out through Candlestick Park’s first season. In the very first game, umpires noticed that both foul poles were situated completely in fair territory instead of on the foul line; they had to improvise new ground rules until the Giants fixed the problem. Both bullpens were moved closer to the dugouts, where foul territory was more voluminous, so outfielders didn’t have to go hunt for live balls that got lost in the area. Outside, $15,000 in repairs had to be made to the parking lot when some of it began sinking through the landfill. And through the first 19 games at the ballpark, six people died of heart attacks when they attempted to trudge from the parking lot up an incline to the front gate on the other side; the earthen ramp was thus nicknamed Cardiac Hill.

Those that survived entry into Candlestick Park next had to face the frigid weather. The city had a plan for that; it embedded 35,000 feet of ¾-inch natural gas piping within the concrete to heat 20,000 of the ballpark’s seats. But they were buried too far within the slab—five inches, as opposed to the one required in the owners’ manual—and thus never worked. Flamboyant San Francisco attorney Melvin Belli, one of 8,200 season ticket holders in the Giants’ first campaign at Candlestick, sued to get his money back—and came to court wearing a parka to visually help get his point across. He won.

The players didn’t like the conditions any more than the fans. Candlestick was particularly tough on right-handed power hitters—and not just because of the wind gusting in from left field; the outfield gaps were set back a lengthy 397 feet from home plate, while center was situated 420 feet away. If that wasn’t enough, a standard hitter’s backdrop was eschewed in favor of a series of cypress trees, generating more complaints from hitters. Candlestick’s first-year numbers that resulted from these handicaps were telling; only 80 homers were hit at the ballpark in 1960—just 34 of them by opponents—and the overall batting average was an anemic .233.

The Giants corrected some of the wrongs for 1961, their second season at Candlestick. They put a proper batting eye behind the trees, and moved the fences in—most extensively in left, where the distance to the gap was shortened 32 feet to 365. This created a large gap between the fence and permanent left-field bleachers, leading to one of Candlestick’s more common sights of kids breaking out the bleachers and fighting for home run balls hit into the void.

Giants great Willie Mays lays off a pitch during a 1965 game at Candlestick Park. Young fans await a possible home run ball behind the fences, while business as usual continues at a shipyard in the distance. (OTBP)

Everybody Knows It’s Windy.

The tougher—nay, impossible—fix remained the winds. They plagued the late innings of day games and often hung around at night, bringing with it a chilly fog that sometimes dipped eerily into the ballpark bowl like the pestilence of death from The Ten Commandments. The side effects were brutal; time often had to be called at home plate when dust devils began swirling out of the infield dirt, while objects from hotdog wrappers to peanut shells danced across the field. Caps were blown off players, leading to the embarrassing chase that seemed to last an eternity. “Bill Russell was playing shortstop for the Dodgers and the wind blew the cap off his head,” recalled Al Michaels to the Examiner. “I swear that cap never touched the grass. It wound up against the chain-link fence in left-center field and Dusty (Baker) had to peel it off.” The wind was strong enough to move a batting cage 30 feet, and once knocked a piano on its side during a pregame ceremony.

The seminal moment that cemented Candlestick Park’s nationwide reputation as an icy wind tunnel took place late in the 1961 All-Star Game. The game began in pleasant, almost hot conditions—but by the ninth inning the cold winds arrived, and with a vengeance. On the mound was diminutive (165 pounds) Giants reliever Stu Miller, facing Detroit’s Rocky Colavito; he was in a set motion and ready to deliver when a fierce gust—one Miller would later say was the strongest he ever felt at Candlestick—knocked him off balance. Miller was never actually blown off the mound as many history sources recycle, but it was enough to disrupt his motion and have a balk called.

What to do with the wind? The Giants asked that question almost from the very moment they set foot at Candlestick Park. They paid a local firm $55,000 to study the wind effects and come up with a solution. The firm’s answer was to cut a slot through Bayview Hill big enough to funnel the wrap-around winds straight through to the stadium—where a partial dome placed over the venue would deflect it away. An estimated $3 million price tag, which was sure to increase, was the price to be paid; the Giants never bothered. Meanwhile, famed architect Buckminster Fuller suggested putting one of his geodesic domes over Candlestick—for $35 million. The Giants quickly shook their heads on that idea as well.

Candlestick’s early years, before the structure was enclosed, were good for the Giants both on the field and at the bank. The team drew a franchise-record 1.795 million in 1960 and stayed well above a million throughout much of the decade. In the standings, the Giants constantly contended behind a roster of future Hall of Famers including Willie Mays, Willie McCovey, Orlando Cepeda, Gaylord Perry and Juan Marichal. They won one National League pennant in 1962—achingly missing out on a world title in Game Seven at Candlestick when McCovey’s would-be series-winning line drive was unfortunately aimed right at the New York Yankees’ Bobby Richardson for the final out; they finished second each year from 1965-69. Marichal, in particular, featured in most of Candlestick’s more memorable games of the 1960s; he threw a one-hit shutout against Philadelphia in his first career start in 1960, tossed the ballpark’s first no-hitter in 1963, and engaged in a remarkable 16-inning duel later that season against the Milwaukee Braves’ Warren Spahn (both threw over 200 pitches) which Mays finally won 1-0 on a walk-off homer. More soberly, Marichal got the worst of his emotions in a 1965 contest against archrival Los Angeles when he took a bat to Dodgers catcher Johnny Roseboro’s head, costing him two starts—and possibly another pennant for the Giants.

Early on, Candlestick Park was rarely used for other events outside of baseball, but it was remembered for a chilly August evening in 1966 when the Beatles played their last public concert. Nobody knew that at the time except for the Fab Four, battered, bruised and pining for the recording studio after a particularly controversial tour that included a run-in with the Philippine government and rage from Southern conservatives over John Lennon’s comment that the group was bigger than Jesus. The Beatles made no mention of their coda to the 25,000 in attendance—and even if they had, the din of screaming girls would have made it impossible for them to be heard.

In 1971, Candlestick Park’s grass was replaced by artificial turf no thicker than a worn-out house carpet. Placed over a concrete base, the fake grass gave no comfort for diving outfielders or (in the case of football) anyone falling to the ground. (KGO)

This Market’s Not Big Enough for the Two of Us.

The Giants’ early success in San Francisco was in part due to the fact that had little competition for the Bay Area’s sports dollar. But that began to change starting in the late 1960s. There were the 49ers, of course—but now the Oakland Raiders, who actually played a season at Candlestick during its infancy (drawing 7,000 customers per game in 1961) had emerged into a powerhouse across the bay at the newly-built Coliseum, part of a sports complex that also attracted pro basketball and pro hockey.

The Coliseum’s other main tenant spelled the biggest problem for the Giants. The Kansas City A’s, languishing and losing for what seemed an eternity, finally packed its bags and moved to Oakland for 1968. They didn’t draw well at the Coliseum, but their presence was enough to eat into the Giants’ gate, dropping Candlestick Park attendance down 35% in 1968 to their first sub-million total since coming to San Francisco. The Bay Area’s population was booming, but it wasn’t enough to convince many that the market could successfully house two major league baseball teams. Sure enough, surveys taken of regional residents showed that barely half of them even cared about sports.

The City of San Francisco, which owned Candlestick, figured it was time to kill two birds with one stone: To move the 49ers into Candlestick from Kezar Stadium, their long-time but decaying home, and to expand and enclose the facility as, fingers crossed, a solution of sorts to cut off the wind. Mayor Joe Alioto initially had visions of a massive domed stadium/convention complex downtown and called any attempt to improve Candlestick as “perpetuating a mediocrity.” But when no one jumped on his bandwagon, he had to eat the criticism and go with Candlestick expansion.

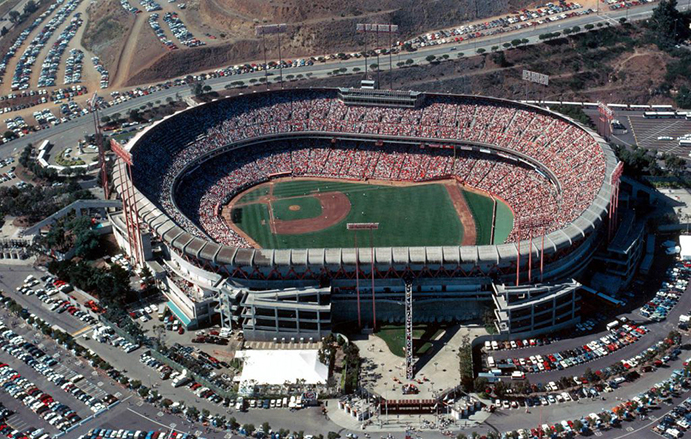

Again under the architectural direction of John Bolles—master builder Charles Harney, who died of a heart attack in 1962, was not available—Candlestick went from a baseball-only ballpark seating 43,000 to a multi-purposed monstrosity with a capacity over 60,000. The lower deck would remain untouched; the second deck was extended behind the left-field bleachers (as originally intended), turned on a straight line behind right field before curling and connecting with the existing upper-level seats along the first-base line to complete the enclosure. Behind the right-field wall, the 49ers would be accommodated with foldout seats that ran a perfect parallel to the football field and connect to the upper deck, while a multi-level, glass-encased press box was inserted at the top of the upper level on the third-base side, knocking out some 400 seats. All original wooden seats would be replaced by plastic red ones, escalators were added outside, and an elevator—something Horace Stoneham groused about not having sooner—was installed. To help pay off the $16.5 million in expansion costs, the city slapped a 50-cent surcharge on Giants tickets, but not those of the 49ers—an odd decision considering that the expansion would benefit the football team more.

Bolles predicted that Candlestick Park’s enclosure would “completely eliminate gusting and swirling winds.” Bolles predicted wrong. There simply was no stopping this wind; it dipped into the stadium and swirled about just as strongly as before. The problem now was, nobody knew which direction it would go. Duane Kuiper, Giants shortstop and later team broadcaster, claimed that in his first game at Candlestick in 1982, catcher Milt May chased a pop foul to the backstop and then gave up, believing it had gone in the stands; on his walk back to the plate, the ball hit him on the head. “(Catching pop flies) would be kind of like dropping an aspirin in a toilet, then flushing and trying to grab it with a pair of tweezers,” recalled Giants catcher/infielder Bob Brenly.

The expansion of Candlestick Park did provide the Giants with a few cool new positives. The insertion of artificial turf and sliding pits meant the end of swirling dust, while left-handed power bats such as Willie McCovey could now make majestic deep flies to right even more impressive as they would land well into the new portion of the upper deck near the right-field pole. (Ken Henderson, in 1972, would be the first to reach those seats.)

After Candlestick Park’s expansion in the early 1970s, a portion of the foldout seats behind right field were still useable for baseball. In later years, those seats became a family-friendly sanctuary for those not willing to sit near fans tanked on alcohol and profanity. (Flickr-David Prasad)

The End of the Stoneham Age.

The 1970s would not be kind for either of Candlestick Park’s tenants. After starting the decade well, the 49ers descended into a prolonged malaise, knocking crowds down into the 30,000 range before the franchise was rescued by owner Eddie DeBartolo and coach/offensive genius Bill Walsh. But the Giants had it much worse. While other MLB owners like the Cardinals’ Gussie Busch (Budweiser), the Chicago Cubs’ William Wrigley (Wrigley Gum) and later the San Diego Padres’ Ray Kroc (McDonalds) had corporate liquid to fall back on, Horace Stoneham had only the Giants within his financial portfolio. The downward spiral would thus be steep.

The Giants’ Hall of Famers began to succumb to age. Horrible trades led to the slipping away of current/future stars such as George Foster, Gaylord Perry, Bobby Bonds and Garry Maddox. A run of 14 straight winning records came to an end in 1972—all while across the bay, the A’s were embarking on three straight world titles with a flamboyant, tabloid headline-generating roster. Bay Area fans had tolerated windy Candlestick and showed up because the Giants were good; but Stoneham was now about to find out if they would support a bad team, stripped of its romanticized star power, in a bad stadium. The answer wouldn’t be pretty.

In both 1974 and 1975, the Giants barely drew 500,000 fans. Against Hank Aaron and the Braves, the Giants attracted 3,600—for an entire three-game series. Any Candlestick crowd that managed to top 20,000 was newsworthy enough to justify a top headline in the Sporting Green section of the San Francisco Chronicle. By the end of 1975, Stoneham was broke; he was a year behind on paying Candlestick rent, owed $1 million to banks and another half-million to the NL, which was helping to pay player salaries. Front office personnel had their pay slashed up to 35%. “The atmosphere around here is very, very bad,” admitted one anonymous staffer to The Sporting News.Stoneham reached the end of the line. He had to sell, and so he did, early in 1976—to Canadian brewery interests who would move the team to Toronto. Not so fast, said San Francisco politicians—who warned that a move out of Candlestick would break the team lease and cause legal friction. But nobody local was coming forward to keep the Giants at Candlestick—that was, until real estate developer Bob Lurie threw his hands up and basically stated that, well, if nobody else wants the team, I might as well buy it. For $8 million and a little help from some business partners, he did.

Worship the Wind.

Lurie inherited a team he knew would lose money on an annual basis—but in his mind, the light at the end of the wind tunnel would be a new ballpark that would change all of that. In the meantime, he had to make do the best he could at Candlestick, which at 17 years of age had already become the NL’s second oldest venue behind Chicago’s Wrigley Field. Modest changes were made, most significantly in 1979 with the reinstallation of real grass—which was actually more of a benefit for the 49ers, who detested the thin layer of virtual carpet spread out over a concrete base. Some baseball players, bristling at the return of swirling dust devils and sod so bad that the team nearly sued the city over it, actually wished for the return of the hard, fake stuff.

Perhaps the most critical update done at Candlestick Park was a $1.1 million retrofit of the upper-deck concrete overhangs, held up by joints that had become weakened from constant moisture. If not for those repairs, Candlestick might have suffered serious infrastructure damage—and numerous casualties among spectators—when the ground shook at the 1989 World Series.

In the 1980s, the Giants began to perform reverse psychology. Through the clubhouse to the players and through savvy marketing campaigns aimed at the fan base, the team espoused the idea that Candlestick should be embraced—because the visiting teams hated it more. There was truth to that; star players would tend to request a day off more than at other ballparks, while others—including Keith Hernandez—made it clear in their contracts that they’d be okay getting traded to any team except San Francisco. The Giants also provided disadvantages to visiting teams by not heating their dugout—the Cincinnati Reds once improvised by firing up two hibachis—and placing their clubhouse clear across the field, meaning a long walk down the right-field line and potential abuse from Giants fans along the way. No one heard the catcalls on this trail louder than long-time Dodgers manager Tommy Lasorda, who often responded by blowing kisses to the crowd.

Even a “modern” venue such as Candlestick Park couldn’t avoid using support beams that obstructed the views of many who were seated behind them. (Flickr—David Prasad)

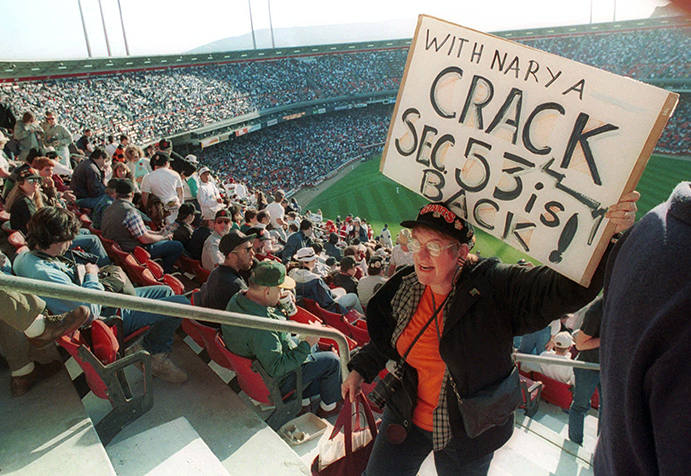

Starting in 1983, Giants fans were rewarded for their heroism of sticking it out through an extra-inning night game at Candlestick by being given orange pins featuring a frosted Giants logo and the words “Vinim, vidi, vixi.” Translation: “I came, I saw, I survived.” The team’s version of a purple heart gave credence to Giants fans who, hardened by years of woe and Candlestick cold, had developed a reputation via some players’ polls as the majors’ worst. Giants players weren’t exempted from the invectives; the fans booed light-hitting shortstop Johnnie LeMaster so mercilessly, he decided to take the field one day wearing “Boo” on the back of his jersey. After one Giants loss during a particularly bad 1984 season, a 30-year-old fan ran perilously down the steep steps of the upper deck yelling abuse at the departing Giants; he lost his balance and fell to his death in the field level below. The Giants took steps to curb the rowdy behavior; they ended vendor sales of beer in the stands, and declared the foldout football seats behind right field, partially useable for baseball, as an alcohol- and profanity-free family section.

Giants general manager Al Rosen and manager Roger Craig—no relation to the 49ers’ All-Pro running back of the same name—particularly imbued a cocky new crop of youngsters (headed by future MVP Will Clark) and newly-arrived veterans (fronted by future 20-game winner Mike Krukow) in the mid-1980s with the “we love it, they hate it” mantra. The players took it to heart; they won NL West divisional titles in 1987 and 1989, taking the pennant in the later year before bowing to the crosstown A’s in a World Series severed in half by the Loma Prieta earthquake.

A Giants fan expresses her loyalty to Candlestick Park in the first game played at the stadium following the Loma Prieta earthquake, which interrupted the 1989 World Series. Had extensive engineering repairs not been done a few years earlier, damage to the venue could have been more tragic. (Associated Press)

Candlestuck.

While the Giants’ players and fans were going through self-imposed analysis to stop brooding about the cold and love Candlestick, Bob Lurie tirelessly tried to find a replacement for the stadium. Then he tried again. And again. And still yet again.

At first the Giants and the city looked into planting an air-supported roof—much like the one that would soon drape the Metrodome in Minneapolis—on top of Candlestick, but Lurie eventually went against the idea. The city then looked into a domed stadium in the China Basin, the same area where the Giants’ current home of Oracle Park sits. It went nowhere. Neither did a downtown stadium/mall project, once the Giants found out it would be financed by season ticket revenue. A 1987 referendum to build a ballpark south of Market Street was defeated by San Francisco voters. Another, in 1989, appeared headed for victory—but that was before the earthquake. The vote took place afterward—and it lost, narrowly. In the middle of all of this, Lurie said he’d move half of his games across the bay to the Oakland Coliseum, where conditions were less chilly. The only problem was, he never bothered to ask the bureaucrats running the Coliseum; they quickly waived him off.

Two more ballpark votes, 40 miles south in the San Jose area, both failed to pass in the early 1990s. At this point, Lurie had enough. He was done with ballpark proposals, done with Candlestick—and done with the Giants. In August 1992, he sold the team to interests in Florida, who were ready to relocate it to a new domed ballpark in St. Petersburg. It was 1976 all over again; once the savior, Lurie was now the reluctant seller. Someone else would have to do the saving.

That someone would be Peter Magowan, the grocery store magnate who forged together a group of investors in the 11th hour and presented a counterbid to buy the team and keep it in San Francisco. The St. Petersburg bid was $15 million higher, but the NL voted 9-4 for the Magowan group. And so Candlestick remained the indefinite home of the Giants, with yet another new owner trying to figure out how to find a better place to play in town.

Like Lurie before him, Magowan quickly and modestly spruced up Candlestick. He filled in the vacant space behind the left-field fence, placing a series of bleachers and putting an end to kids chasing after home run balls in the void. The right-field gap was reduced to 365 feet, matching left field dimensions. A foghorn was installed, sounding off whenever the Giants hit a home run. And advertising was placed on the outfield walls—most cleverly with panels in the gaps that simply said “Gap”—paid for by the clothing store of the same name.

Magowan also ramped up the nostalgia of Candlestick’s earlier, more beloved times. He brought Willie Mays on as a virtual team ambassador, made Bobby Bonds the hitting coach and, über-crucially, signed Bobby’s son Barry, like Mays a genuine five-tool talent, to a then-record $43.75 million contract over six years. The 1993 team, Magowan’s first, won 103 games before a Candlestick record-shattering 2.6 million fans—but in the year before the wild card was instituted, the Giants stunningly failed to make the postseason. Worse, despite the sudden upbeat vibe at Candlestick, the Giants could only manage a relatively minor $200,000 profit. The threshold for reaching the black was too high to continue playing at the aging stadium.

Carefully, Magowan went to work on securing a new ballpark. The Giants worked all corners of the city’s diverse community and, more importantly, said they would finance a new ballpark without public funds. That was too great an offer even for typically naysaying San Franciscans to refuse; in March 1996, they easily voted yes to what is now Oracle Park.

Candlestick Park was firmly isolated from the rest of San Francisco, nowhere near any transit centers, bars, restaurants, or community—until a series of condominiums (shown here in front of the stadium) cropped up in its later years. (Flickr—Niall Kennedy)

The Autumn Winds.

The Giants played their final game at Candlestick Park in 1999, wrapping up 40 years of play at the stadium. They moved on, but the 49ers remained. Candlestick’s enclosure and ensuing upgrades had made the stadium more football-friendly, and the 49ers benefited more from San Francisco’s fall weather which, with less blustery fog and more warmth, was more comfortable for gridiron fans. But Candlestick’s remaining occupant wanted out, too; the place was just getting too old and outdated. That was made apparent during a Monday Night Football game in 2011 when the lights went out—twice. In a bizarre turnabout from the Giants’ earlier predicaments, city voters twice approved new or improved venues for the 49ers—but the team said no thanks, as they focused on a new stadium next to their training facility in the San Jose suburb of Santa Clara, 40 miles to the south. That became reality in 2010 when Santa Clara voters gave the okay for Levi’s Stadium, which opened in 2014.

Candlestick’s last serious sporting event took place in May 2014 when the U.S. men’s national soccer team took on Azerbaijan. Less seriously, a benefit flag football game featuring former 49ers greats such as Joe Montana occurred later in July before roughly 25,000 spectators. Fittingly, the last Candlestick Park event, period, was an August concert given by Paul McCartney—whose Beatles had publicly performed for the last time at Candlestick 48 years earlier.

There was talk that the Giants would play one last series at Candlestick, for old times’ sake. But Candlestick had become too petrified; the retractable football seats, permanently folded out for 15 years, couldn’t be tucked away because all the joints had become rusted. So the reunion never took root.

Former Giant Jack Clark once said that the best way to improve Candlestick Park was with “dynamite.” Similar sentiments were shared by many who had suffered through the stadium’s gray, Soviet-style architecture and brisk Siberian weather; they now longed to see it leveled with a single blast, an exorcism of past miseries. But instead of a bang, Candlestick went with a whimper. Quietly, piece by piece, the stadium was disassembled—and then, without almost anyone noticing, it was gone. The place that hosted Mays, McCovey, Marichal, the Baby Bull, back-to-back no-hitters in 1968, pitcher Tony Cloninger’s two grand slams in a 1966 game, baseball’s one-millionth run scored by Bob Watson in 1975, Dave Drevecky’s inspirational 1989 comeback, Will the Thrill, Bonds and Bonds—all gone.

Gone with the wind.

The Ballparks: Oracle Park In the annals of baseball, home runs have landed in places as varied as apartments, auto dealerships and snowbanks. But hardly ever into water. Oracle Park, with its glorious views of San Francisco Bay, has become the first park in the majors to allow a crushing drive to make a splash landing, past the slim right-field bleachers and into aptly-named McCovey Cove—where a potpourri of aquatic adventurists anxiously await their chance to scoop up a souvenir.

The Ballparks: Oracle Park In the annals of baseball, home runs have landed in places as varied as apartments, auto dealerships and snowbanks. But hardly ever into water. Oracle Park, with its glorious views of San Francisco Bay, has become the first park in the majors to allow a crushing drive to make a splash landing, past the slim right-field bleachers and into aptly-named McCovey Cove—where a potpourri of aquatic adventurists anxiously await their chance to scoop up a souvenir.

The Ballparks: The Polo Grounds Peculiar doesn’t even begin to describe the Polo Grounds, a bathtub of a ballpark that yielded pop fly home runs and tape-measure outs as it led almost as many lives as a cat against the rocky bluffs of Harlem. Through its resiliency, it manifested more than its share of baseball’s legendary moments and unforgettable actors, whether it was McGraw, Mathewson, Merkle, Master Melvin, Mays or, yes, even Marvelous Marv.

The Ballparks: The Polo Grounds Peculiar doesn’t even begin to describe the Polo Grounds, a bathtub of a ballpark that yielded pop fly home runs and tape-measure outs as it led almost as many lives as a cat against the rocky bluffs of Harlem. Through its resiliency, it manifested more than its share of baseball’s legendary moments and unforgettable actors, whether it was McGraw, Mathewson, Merkle, Master Melvin, Mays or, yes, even Marvelous Marv.

San Francisco Giants Team History A decade-by-decade history of the Giants, the ballparks they’ve played in, and the four people who are on the franchise’s Mount Rushmore.