The Ballparks

The Polo Grounds

New York, New York

Peculiar doesn’t even begin to describe the Polo Grounds, a bathtub of a ballpark that yielded pop fly home runs and tape-measure outs as it led almost as many lives as a cat against the rocky bluffs of Harlem. Through its resiliency, it manifested more than its share of baseball’s legendary moments and unforgettable actors, whether it was McGraw, Mathewson, Merkle, Master Melvin, Mays or, yes, even Marvelous Marv.

When one begins to take the first steps into the history of the Polo Grounds, irony and confusion quickly reign. The first question usually is, why did they call it the Polo Grounds when polo was never played there? The second might be, if it was built for baseball, why was it shaped to look like it had rectangular sports like football or soccer more in mind? And lastly, what’s with all the roman numerals historians place after the name, as if the ballpark was some successful Hollywood movie franchise with multiple sequels?

So many questions, so much history for a ballpark with so much unusual character. And there was nothing more unique about the Polo Grounds than its playing field, which looked less like the traditional pizza slice and more like a rectangular Kellys douche pad with the bottom corners diagonally cut away. This resulted in an extreme disparity of field dimensions unlike anything seen in a major league ballpark; as the Polo Grounds giveth, the Polo Grounds taketh away. It just depended on where you hit the ball.

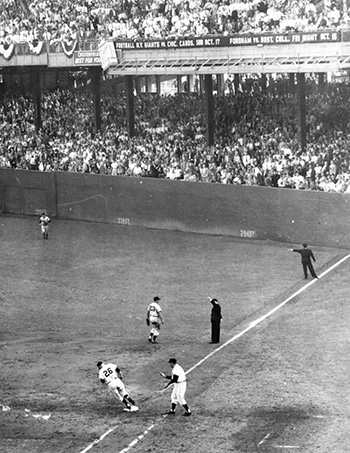

The ultimate irony produced by the Polo Grounds’ wacky field geography occurred in Game One of the 1954 World Series, a contest that would spark the ballpark’s last great hurrah for the New York Giants before their move to San Francisco. In the top of the eighth inning with the game tied at 2-2, the visiting Cleveland Indians had placed their first two batters on base and up came slugger Vic Wertz, who launched a deep, bruising drive toward center field. This would have been a no-doubt-about-it, three-run homer in any other ballpark. But not at the Polo Grounds—and not with the speedy Willie Mays patrolling the vast center-field landscape. Mays bolted toward the distant wall, well past the point where most center field fences are nailed down at other ballparks, and caught up to Wertz’s drive with an unbelievable over-the-shoulder catch that would forever be remembered, simply, as “The Catch.”

Wertz apparently didn’t understand the politics of hitting to the Polo Grounds’ sweet spot. Dusty Rhodes did. In the bottom of the 10th with the game still knotted at 2-2, Rhodes came off the bench (as he often did) and hit a soft fly ball that barely cleared the right-field wall next to the foul pole—a mere 257 feet and change away from home plate. Wertz’s tape-measure rocket had traveled nearly 200 feet further, but all he got for his troubles was a hitless at-bat. Rhodes’ three-run pop-up won the game for the Giants, initiating a four-game sweep of the Indians. Only at the Polo Grounds.

Rhodes, a left-handed hitter with dead pull tendencies, was tailor made for the Polo Grounds. In the 70 years that baseball was played at the ballpark’s main location under Coogan’s Bluff, only a dozen players hit three homers in a game—and Rhodes was the only one to do it twice. Not bad for a guy who had just 54 for his entire career—with 40 of them alone at the Polo Grounds, most we assume hit down the short right-field line.

The walk-off chip shot from Rhodes, preceded by Mays’ sprinting catch of lore, was just the tip of the iceberg when it came to the storied memories of the Polo Grounds. It’s the place that hosted arguably the game’s biggest gaffe when Fred Merkle failed to touch second base in a premature celebration that likely cost the Giants the 1908 pennant. It’s where the majors’ only on-field death occurred when the Yankees’ Carl Mays struck the Indians’ Ray Chapman with a pitch to the head in 1920. It’s where the Giants’ Carl Hubbell struck out five straight American League legends in the second-ever All-Star Game in 1934. It’s where a bounty of famed streaks took place, including Hubbell’s 24 straight wins from 1936-37, Rube Marquard’s 20 straight from 1911-12, and an all-time record 26 consecutive victories registered by the Giants (all at home) in 1916. Finally, the Polo Grounds is where, quite possibly, the single most famous moment in the history of the sport took place when, in 1951, Bobby Thomson launched the Shot Heard ‘Round the World with his dramatic game-winning homer that capped the Giants’ remarkable comeback pennant over the archrival Brooklyn Dodgers.

Where Polo Was Actually Played.

The whole Polo Grounds phenomenon began in 1880, two and a half miles to the south of where it would end 84 years later. Baseball had sprung like wildfire in New York City following the Civil War, but it had been without a major league outfit for three years when John Day, a local tobacco shop owner and member of New York’s highly powerful (and highly corrupt) Tammany Hall political community, decided to fill the void by starting up a freelance team. To play his games, he got permission to use an expansive field built a few years earlier for polo called, naturally, the Polo Grounds. Located just a few blocks from the northeast edge of Central Park, the yard hosted its very first baseball game on September 29, 1880 when Day’s team, called the Metropolitans, defeated the National League’s Washington Nationals 8-3 in a game cut short to six innings due to darkness and the Nationals’ late arrival.

The Metropolitans were such a success and the Polo Grounds such a big place, Day thought, why have one club when I can squeeze two onto the property? So in 1883, he took over the grounds, pulled the Mets off the independent circuit and enrolled them in the upstart American Association, while creating a whole new NL team called the Gothams—who two years later were renamed the Giants after Day’s business partner Jim Mutrie had praised them as such. Two ballparks, both with two-level wooden grandstands, would be built on the Polo Grounds, with the outfields backing into one another; all that separated them was a canvas curtain. If a live ball went under the curtain, the umpire didn’t declare a ground-rule double; it was the outfielder’s responsibility to crawl underneath and make a surprise appearance at the game next door to retrieve it.

In the standings, the Mets were the more successful of the two teams early on, but the Giants clearly became the darlings at the gate. Former president Ulysses S. Grant was among the many to attend the very first Giants game in 1883; three years later, the Giants attracted a then-record crowd of 20,709. Meanwhile, the Mets’ attendance woes were exposed when, during its participation in the first “World Series” between competing leagues in 1884, they drew only 1,000 for the second game a measly 300 for the third as the NL’s Providence Grays easily brushed them aside in a three-game sweep by a combined score of 20-3.

The Giants took over as the last team standing at the Polo Grounds after the Mets’ demise in 1887 and won the NL pennant in 1888, but Day apparently wasn’t giving enough love (in the form of free tickets) to his fellow city cronies. In response, they decided to put a street right through the grounds, making baseball inhabitable and rendering the Giants momentarily homeless. What remained of Day’s friendly Tammany connections apparently couldn’t stop it, thus ending the reign of Polo Grounds I—or I and II, as some historians refer to the two ballparks separately while others consider the pair as a collective one.

A look at two ballparks named the Polo Grounds: The one at bottom used by the Giants from 1889-90, and the one they would move into afterward, top left. The one at bottom would be renamed Manhattan Field, which within five years would be torn down. (Library of Congress)

Drain the Swamp.

While the Giants searched in vain for a temporary home—at one point they had to play their early-season games of 1889 at a Staten Island ballpark that doubled as an outdoor theater, complete with stage in right field—they eyed a swampy expanse in northeast Manhattan, wedged between the Harlem River and a rocky 140-foot cliff known as Coogan’s Bluff. At high tide, part of the land actually became the river; Fred Logan, who would serve as the Giants’ clubhouse attendant for 58 years until 1947, recalled fishing for eels there as a young boy. But thanks to the concept of landfill, the Giants saw their future at the locale and built their new ballpark. And what would John Day name it? The New Polo Grounds, but of course. Never mind that polo had nothing to do with it; the brand was more important.

Because they wanted to get the hell off of Staten Island, the Giants took an incredible three weeks to quickly build the new facility. Too quickly, perhaps; at its first game, a loud crack was heard in the second level of the main wooden grandstand, and officials fearing an imminent collapse ushered the fans out. No fracture was ever found.

The New Polo Grounds would include 14,000 seats, most of them hugging an elongated left-field line along 155th Street, south of the facility; on the first-base side of the main grandstand, a three-story building that could have been confused for a chalet housed, among other things, the teams’ dressing quarters. The Giants were already a solid team, but their midseason arrival at the new yard made them feel very much at home; they won 29 of the 37 games at the New Polo Grounds and came away with another NL title.

A second straight pennant had led to a second straight winter of discontent for John Day and the Giants. Whereas he had lost his ballpark a year before to a newly paved street, he was now about to lose the bulk of his roster to a newly formed big league circuit. The Players League, formed by major leaguers tired of scrupulous owners suppressing their wages, would include a team in New York; more than half of the Giants, including six future Hall of Famers, jumped at the chance to split to the new league.

They didn’t have to jump far. Day had built the New Polo Grounds on half of the available land, but he didn’t own it; that was the property of James Coogan, who was all relation to Coogan’s Bluff. The new Players League team, which not only stole the Giants’ star players but even the team name, wanted to lease the other half of the meadow; Coogan obliged. The new 16,000-seat yard built by the PL Giants would be named Brotherhood Park and include a single-level grandstand and plenty of bleachers—but because the space they got was a rectangular plot, they had to lay out the field so it was horizontally condensed but vertically (from home plate to center) extended to compensate for the short distances down the lines.

The PL Giants outperformed and outdrew the NL Giants, but in the end there would be no winners. The Players League, badly underfunded, folded after just one year. And although Day’s Giants would survive, Day himself wouldn’t; the financial dent incurred by the PL was significant enough to force him to sell within a few years—but not before moving the Giants from the New Polo Grounds to Brotherhood Park, adding a second deck to the grandstand, and renaming the venues. The New Polo Grounds—a.k.a., Polo Grounds II, or III—would become known as Manhattan Field, while Brotherhood Park would be changed to, you guessed it, the Polo Grounds. Or Polo Grounds III, or IV, depending on your historical point of view.

Manhattan Field would be a profitable accessory in the short term. Among the many events that would be held there, college football (mostly Ivy League teams) drew the most spectators with crowds up to 50,000. But when the onerous Andrew Freedman, a man with little vision but plenty of spite, bought the Giants in 1895, he saw no value in Manhattan Field. He tore down the grandstands and sold off the wood, while the field became a tall, weed-infested wasteland. In the years to follow, Manhattan Field would take on many existences; at one point it was a cricket field, and during the Polo Grounds’ later years, it became a paved parking lot not only for Giants fans but for those of the Yankees, who had only a short walk across the Harlem to reach nearby Yankee Stadium.

One had to wonder if Freedman would wreck apart the Polo Grounds as well. He hired and fired managers at a dizzying frequency that would have made even George Steinbrenner’s head spin, clashed with star players, barred umpires he didn’t like and reporters who dared to criticize his team, all while the Giants became irrelevant in the standings. By 1902, as Freedman lobbied for a brand of “syndicate baseball” that likely would have ruined the game, fellow owners had become fed up with him. But before getting the message and bowing out, Freedman made two moves that would right the Giants for years to come by bringing in a young, well-schooled pitching prodigy named Christy Mathewson, and a pit bull of a tyrannical (but highly effective) manager in John McGraw. Both moves were engineered by Cincinnati owner John Brush, who helped McGraw jump ship from the upstart rival American League (for which McGraw had developed a raging hatred for) as he successfully eyed Freedman’s departure as a chance to take ownership of the Giants themselves.

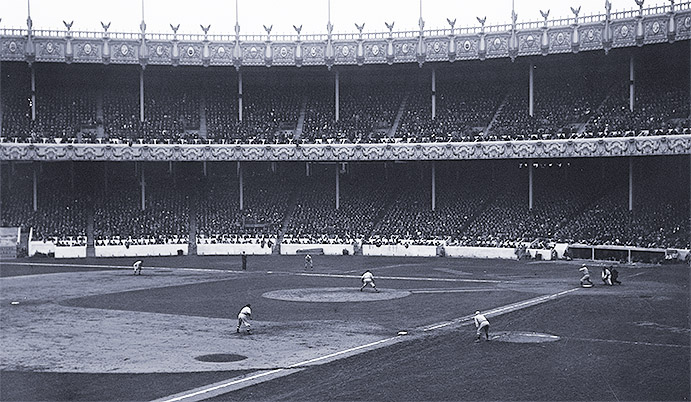

The wooden version of the Polo Grounds, during the 1905 World Series. Notice the absence of outfield bleachers; fans with horse carriages were allowed to park on its parameter. (Library of Congress)

McGraw the Merciless.

Over the next 10 years, the Giants would provide Polo Grounds fans with a robust, in-your-face brand of winning baseball that rubbed off on a rowdy fan base and made the Giants the NL’s #1 home draw for 18 of 23 years starting in 1902. The pugnacious McGraw craftily bullied opponents, umpires and even other owners while being gifted with a remarkable sense of molding a talented team in his disposition. Among McGraw’s breed was workhorse pitcher Joe McGinnity, the devil in an incomparable ace duo to complement the angelic Mathewson and author of many doubleheader conquests in which he started and won both games; and outfielder Mike Donlin, whose weakness was a devotion for the stage and the fistfight that rivaled his love for baseball. With his new cast in tow, McGraw quickly turned the Giants from second-division wanderers into a consistent contender that won back-to-back pennants from 1904-05—the latter resulting in a World Series conquest over the Philadelphia Athletics in which Mathewson and McGinnity, essentially pitching the entirety of the five-game series, didn’t allow a single earned run over 44 innings.

A third pennant under McGraw looked to be in the cards for 1908, but Fred Merkle went and screwed it all up.

A 19-year-old rookie, Merkle was part of an apparent game-winning rally over the rival Chicago Cubs in an early September game. But when Al Birdwell’s single sent home the winning run, Merkle—who was on first base—never bothered to complete his required 90-foot jog to second on the play. The observant Cubs noticed, tagged second amid a manic celebration of players and fans from the Polo Grounds crowd of 20,000 who had entered the field, triggering a whirlwind of controversy in the days to follow in which the NL ruled the game a tie—declaring Merkle out but blaming impending darkness for the inability for the game to continue into extra innings. The game would only be replayed, the NL decreed, if the Giants and Cubs finished the regular season tied for first. Sure enough, as destiny sometimes presages, the two teams wrapped the schedule with identical 98-55 records. Now came a one-game playoff at the Polo Grounds. All because of what is now known as, pardoning the expression, the Merkle Boner.

John Brush added 7,000 seats to the Polo Grounds during the year as the Giants were on their way to drawing a then-record-setting 910,000 spectators, but adding 70,000 more chairs still wouldn’t have been close to accommodating the 250,000 who descended upon the ballpark to get any kind of glimpse, paid or unpaid, for the highly charged replay. Bobby Thomson’s historic 1951 homer is often labeled the Miracle at Coogan’s Bluff, but the true miracle on this October day was that the Giants-Cubs replay got in without a riot—before, during or after the game.

A crowd of 40,000 jammed the park; they were the lucky ones. Outside, Coogan’s Bluff was overwhelmed by humanity as thousands sought a partial free view of the game; others improvised the best they could, climbing telephone poles and trees—with a few reportedly falling to their deaths while trying to do so. Those otherwise lacking any kind of view attempted to force their way in by burning down the fencing behind the bleachers.

The Giants lost the replay, 4-2, as Christy Mathewson faltered early on, but the victorious Cubs had one last hurdle to cross after the final out: Surviving the long walk—or in this case, the long sprint—clear across the field to the clubhouse behind center field. It was a dubious postgame ritual for many years at the Polo Grounds as fans were permitted on the field after games to more quickly reach the exits; players often ran to avoid memorabilia hawks who sought to steal gloves, caps, etc. But in this case, the Cubs were on the run for their very lives. Belligerent Giants fans who felt their team had been cheated out of a pennant took out their anger by throwing or lunging sharp objects at Chicago players, injuring a few of them.

New York Giants players and officials survey the damage to the Polo Grounds a day after the wooden facility burned to the ground. (Library of Congress)

After the Fire.

In 1911, the Giants lost their first two games at the Polo Grounds—and then they lost the Polo Grounds. A night after the second loss, the ballpark caught fire and spread rapidly, engulfing all but the detached outfield bleachers. Many other ballparks had burned to the ground, but none as spectacularly; those on the scene described the fire as a vast “sea of flames,” a blaze so intense that its glow could be seen for 10 miles. The cause was never proven, though the most redundant rumor centered around a newspaper or program that caught fire from a discarded cigarette under the grandstand.

The Giants wasted no time; they couldn’t afford to do otherwise. But John Brush wasn’t just going to hash together something, anything in the name of beating the clock, either. The frail Giants owner set about to make sure that the Phoenix rising from the Polo Grounds’ ashes would become “the last word in baseball architecture.”

To design the replacement, Brush hired New York City architect Henry Beaumont Herts, who specialized in theater design; it didn’t hurt that he also excelled in fireproofing. Herts gave the new structure a strong dose of ornamentation; the higher the ballpark went, the more ornate it got. The facing at the base of the upper deck facing featured repetitive bas relief motifs that came across as elegant but generic. Things got more substantive on the overhang facing, graced with decorative reliefs of all eight NL teams in repeated fashion; not only were they superlative in their design, they were said to be far more colorful than visualized by anyone seeing them today through grainy black and white photographs.

The splendor didn’t end there. Atop the roof was an ironworks-style fencing adorned every 20 feet or so by statues of eagles with their wings spread upward. While the left-field end of the grandstand was left bare on the side, the right-field side was beautified by an extravagant arch and other gothic touches. Within the stands, the Giants had every aisle-facing seat adorned with the florid “NY” insignia, a tactic that would be repeated by ballparks of the future—particularly those of the retro era that began in 1992 with Oriole Park at Camden Yards.

Optimal sightlines were figured into the grandstand design, as the field level between the foul poles was formed as a semi-circle to surround foul territory; this was done so every seat would face directly toward the pitcher’s mound. The upper deck followed suit, except for an extended portion down the right-field line which straightened out and continued past the foul pole.

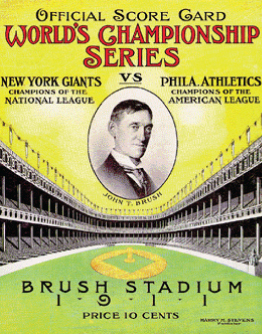

A program for the 1911 World Series features the rebuilt Polo Grounds, named Brush Stadium after Giants owner John Brush. The name didn’t catch on.

The reborn Polo Grounds was widely praised; Allan Sangree of Baseball America called it “the mightiest temple ever erected to the goddess of sport.” John Brush tried to associate himself to such commentary and rename the ballpark Brush Stadium, but no one—not even the Giants, ultimately—really ever took to it. That’s a shame considering that Brush put most of his money into the rebuild and had precious little time to soak it in. Handicapped, Brush watched the games from a car parked in a notch of foul territory near the right-field foul pole until his death following the 1912 season. Memoriam be damned; everyone liked the name Polo Grounds, so Polo Grounds it remained. Or Polo Grounds IV. Or V.

Rise of the Babe Boomer.

While the Giants rebuilt the Polo Grounds in early 1911, the American League’s New York Highlanders offered up their ballpark, the plain, wooden Hilltop Park, as temporary refuge. To say this was a gracious move was putting it mildly. The Giants had forever stuck it to the Highlanders and the AL; John McGraw had been kicked out of the infant circuit in 1902 and, when the Giants won the 1904 NL pennant, he refused to play the World Series because he didn’t want to waste time proving his team’s value against an “inferior” league. John Brush was no more congenial, saying upon the Highlanders’ arrival in 1903 that he would not share the Polo Grounds or lease out adjacent Manhattan Field, not even for “a million a year.” But in 1913, with new ownership taking over for the late Brush and McGraw mellowing—just a little bit, anyway—the Giants responded in kind, allowing the Highlanders to rent out the Polo Grounds for 10 years. The Highlanders’ first move would be to change their name, becoming henceforth known as the New York Yankees.

The introduction of American League baseball to the Polo Grounds also meant the presence of star power for which the AL, by now the stronger loop, had monopolized. The great Shoeless Joe Jackson, playing for Cleveland in 1913, flexed his muscles and became the first player to hit a home run off the top of the right-field roof and out of the ballpark; he was also one of two players to land one in the distant center-field bleachers before the Polo Grounds’ expansion, in 1923, pushed them back even further.

The other star who raked the ball that far would have a profound effect on New York baseball for decades to come.

Babe Ruth had arrived in the majors as a highly praised pitching prospect and, by 1915 at age 20, had become part of the Boston Red Sox’ esteemed rotation. But when he took the field at the Polo Grounds for the first time against the Yankees on May 6, 1915, he also showed off his other superior skill: Knocking the socks out of the dead ball. In his first at-bat at the Grounds, Ruth hit his first of 714 career home runs. When he returned a month later, he hit his second.

Ruth loved the Polo Grounds and its short right-field porch. But unlike the aforementioned Dusty Rhodes, Ruth didn’t need to rely on a short 257 feet to the foul pole; he could land it anywhere in any ballpark, no matter how deep. With the Polo Grounds in particular, Ruth showed that the deadball era’s days were numbered. Through 1919 with the Red Sox, Ruth drilled 10 home runs with 24 runs batted in—in all of 95 at-bats. For perspective’s sake, this was done during a time when hitting 10 home runs over an entire regular season was considered an impressive achievement in slugging. For the last of those 10 homers at the Grounds, on September 24, 1919, Ruth did one better than Joe Jackson: He blasted a ball over the right-field roof. Incidentally, that home run was his 28th of the year, breaking Ned Williamson’s all-time season record.

Needless to say, Babe Ruth was just warming up.

The Polo Grounds during the 1912 World Series, a year after being reconstructed using steel and concrete with ornamentally garish facades. (Library of Congress)

After the 1919 season, the Red Sox sensed they had a one-of-a-kind talent with Ruth—and so they sold him, because owner Harry Frazee badly needed the money. And money is what he got a lot of from the Yankees, to the tune of $125,000 plus a $350,000 loan—a staggering amount of baseball dough for its day.

For the Yankees, the money was well spent—even if it took 15 years to collect the entirety of the Red Sox’ loan. In 66 home games at the Polo Grounds in 1920, Ruth hit .399 with 29 homers; he added 25 more on the road, giving him 54 to nearly lap his record-setting total of the year before. A year later, he was even better—launching 32 bombs at the Grounds alone while hitting .402, helping to swell his overall season numbers to an astonishing 59 homers, 168 RBIs, 177 runs scored and 145 walks to go with a .378 average.

For the Giants, the rise of Ruth and the Yankees—who had been given other star talent from the cash-strapped Red Sox—began to make them feel like second fiddle within their own ballpark. Their own performance had little to do with it; John McGraw continued to bring in top-notch players, and his team continued to thrive in the standings. But they didn’t make headlines like Ruth. In 1920, the Giants set a National League record by hauling in 929,000 fans. But that was a distant second to the Yankees, who that same year with Ruth became the first in major league history to top a million—and rather easily, at 1,289,422. The Polo Grounds had become a busy place; it was about to get even busier.

In 1921, both the Giants and Yankees fielded rosters loaded for the long run and it showed when both teams took pennants, making the Polo Grounds the first ballpark to host an entire World Series. It happened again in 1922. In both instances, the Giants prevailed as champions, besting the Yankees and keeping Ruth—who hit .212 with a single homer in 11 combined games—off his A-game.

The twin conquests of the Yankees soothed McGraw’s ego, but only to a point. He still abhorred the American League, hated Ruth and everything he stood for. Though McGraw didn’t own the Giants, he wielded enough say; he had plugged his nose enough while the team collected rent and concession revenue from the Yankees, but as Ruth began to bask in the New York baseball spotlight, the status quo could no longer be tolerated. McGraw convinced ownership to boot the Yankees out of the Polo Grounds once their lease expired at the end of 1922, believing that the Yankees would have a hard time finding (a), any new land in Manhattan or (b), any ideal spot outside of the island to build their own ballpark. While (a) proved to be true, (b) didn’t. The Yankees struck gold by finding premium land in the Bronx, literally right across the Harlem from the Polo Grounds, with better rail access. Yankee Stadium, the most majestic and massive (over 70,000 seats) ballpark yet, would be ready in 1923 and serve the Yankees and their unparalleled reign of greatness for the next 87 years. The Stadium’s presence clearly showed that McGraw’s spite had gotten the best of him and, although he had a few more pennants in him, it marked the beginning of his decline.

The Polo Grounds in the midst of expansion during the 1923 season. Apparently security was okay with fans sitting in the unfinished upper deck near the left-field foul pole. (Library of Congress)

You’re Going to Need a Bigger Ballpark.

In response to Yankee Stadium, the Giants immediately decided to expand the Polo Grounds to 55,000 seats, not so much to draw more fans for baseball but to lure other events to the ballpark as a means of producing more revenue. Because if the Giants didn’t, the Yankees would, and leave the Polo Grounders further behind in baseball’s rat race for supremacy.

The double-decked grandstand was continued down the lines, straightened out rather than curved around the infield as initially designed, and took a sharp turn well past the foul pole toward center. Rather than enclose the second deck completely around the field, uncovered bleachers filled in the rest of the space behind the outfield, themselves separated by a tall, dark green edifice that rose like a castle-like façade some 100 feet into the air, serving as the batter’s eye and space for both clubhouses and the Giants’ main offices. This structure was recessed to be flush to the back of the bleachers, leaving playing space in front of it—resulting in the furthest distance from home plate not only at the Polo Grounds but in all of baseball at the time, as much as 505 feet. For out-of-breath outfielders entering this area in pursuit of a ball, it felt like entering a cluttered two-car garage. It included a covered area at the far back which hid chairs, hoses and other groundskeeper-related accessories; was fronted by a single post which included at its base a monument to Eddie Grant, a former Giant who was the only major leaguer to die in combat during World War I; and on each side wall ran a set of stairs that led players to their dressing rooms.

Outside of center field, the Polo Grounds’ bizarre outfield shape remained the same. Rather than cradle the infield in semi-circular fashion like most ballparks, the Grounds’ outfield wall shot away from the short foul pole placement on a straight line parallel to the imaginary line from home to center—and then via a rounded corner made a 90-degree turn toward center, again running straight. Outfielders in left and right had to play back toward center because any ball striking off the parallel portion of the wall would skim toward deep center, rather than carom back toward the infield.

Additionally, left fielders had it tougher because of the second-deck overhang past the foul pole. Detroit’s Tiger Stadium gets plenty of writing ink and online bytes for its right-field second deck that stuck out 10 feet above the warning track, but that had nothing on the Polo Grounds, where the upper deck in left extended 20 feet outward. This actually made the 279-foot marker down the left-field line even shorter—physics dictated something closer to 250—and outfielders sometimes struggled to keep a decently hit pop fly within their sights without the overhang getting in the way.

The quirks continued in the gaps. Some 450 feet away from home plate, against the tall wall at the corner in right-center and left-center, lay the bullpens—the only ones placed in fair territory at a major league yard. The only difference between the two? The Giants’ pen, on the right-field side, would get afternoon shade and was outfitted with a canopy; the visitors’ pen, at left-center, got neither—leaving their players to roast on a hot afternoon. In 1947, Philadelphia manager Ben Chapman—who made bigger headlines that year for his racial taunting of Jackie Robinson—kept his relievers in the dugout rather than sacrifice their skin cells on a boiling New York summer afternoon. His protests were heeded and the visitors’ bullpen soon got its roof.

Aesthetically, the main casualty of the Polo Grounds’ expansion was the elimination of the decorative motifs graced upon the upper deck facades by Henry Herts. It was reasoned that their removal was due to safety for the fans, who risked injury when a foul ball struck one of the concrete reliefs, cracked and fell below. Yet no imagination was afforded in their replacements, a bland, dark-green facing that relegated the look of the interior to industrial utilitarianism. Outside, the ballpark’s exterior displayed a mild dose of schizophrenia; whereas the view looking at the west (home plate) end was orderly and even minimalistic, the east end by contrast was a mishmash of criss-crossing ramps, white brick and grill-like wall protection—all topped by a simplistic ornamental frieze not unlike something borrowed from a cheesy, castle-themed motel.

To bring in more non-baseball activities to the expanded Polo Grounds, the Giants established the National Exhibition Company (NEC) that would serve as the team’s corporate arm. It may sound like one of those benign but inconspicuous entities hiding evil intentions, but it was all quite legit and did well to attract events and tenants to fatten the Giants’ bank account. In 1925, the New York football Giants started up as a new franchise in the fledgling National Football League, feeling right at home in the Polo Grounds’ bathtub-shaped configuration that seemed to accommodate football as conveniently as baseball. Big-time college football also reigned, with the venue hosting the prestigious Army-Navy game nine times. Nearby Fordham University, a major power in its day, played to capacity crowds. And then there was boxing; a September 1923 bout between Jack Dempsey and Luis Angel Firpo attracted a gathering of 82,000, the largest for any event at the Grounds. The fight also likely led to the largest headache for groundskeeper Henry Fabian, who had to clean up the wood planks and loose nails that covered the field. Fabian said it was the toughest chore he ever had to perform, less than two weeks before the Giants returned for their final homestand of the season and, shortly thereafter, the 1923 World Series.

The Polo Grounds and Coogan’s Bluff behind it, as seen from the distant upper-level seats behind right-center field. The graceful ornamentation has been stripped away from the upper-deck façade and overhang, relegating the ballpark’s aesthetic to something more drab and industrial. (The Rucker Archive)

Firsts and Worsts.

After relocations, rebuilds and reinventions, the Polo Grounds finally settled into cruise control for the long term starting in the mid-1920s. The structure that resulted from the 1923 expansion would, by and large, remain the same through to its last days.

Of course, there would be tweaks as the years went along. In 1929, the Polo Grounds became the first major league ballpark to use a modern public address system; they tried wiring up the umpires as well, but that didn’t work out so well. Ten years later, the Giants started the trend of adding two feet of hard screening to the fair side of the foul poles to better assist umpires having to make a close call on a potential home run, a kneejerk reaction to a feisty brawl between the Giants’ Billy Jurges and umpire George Magerkruth after the latter called the former’s drive down the line foul. And in 1940, the Polo Grounds joined the growing parade of ballparks outfitted for lights by hosting its first night game, a 6-2 Giants win over the Boston Bees (nee Braves). The eight towers placed upon the roof cost $125,000.

Some things remained unchanged, to the chagrin of many. The two hand-operated scoreboards, placed behind each foul pole on the upper deck facing, was increasingly criticized as being too antique—even if the boards contained detailed information and were flawlessly handled by a small army of operators. Below, groundskeepers had to occasionally truck in loads of new dirt to even out the playing surface above the Polo Grounds landfill; it was said that the outfield sunk so often, managers could only see the top third of the outfielders from the dugout. More intentionally, the Giants for some years developed an infield that didn’t lie flat but instead rose 21 inches toward the edge of the mound—a “turtle-back” tactic employed by groundskeeper Henry Fabian that befuddled infielders (especially those on the visitor’s side) and was thoroughly endorsed by John McGraw. Bill Terry, who took over as McGraw’s successor in 1932, got rid of it.

Members of the press were initially ecstatic to learn that a new press box would be built under the second deck behind home plate, replacing the field-level space where reporters were continuously distracted by fans, team officials and celebrities who saw no big deal in crashing the area. But it didn’t take long for writers and broadcasters to grow an intense hatred for what they decried as a cramped, downright hot press box with chicken wire for protection and no bathroom. The Giants ignored the press’ pleas for improvement, and insult was added to injury when a much nicer press area was built for football writers atop the second deck behind right field—or, as translated to the gridiron layout, the 50-yard line.

For Giants broadcaster Russ Hodges—immortalized for repeatedly shouting, “The Giants win the pennant!” on air as Bobby Thomson circled the bases following his “Shot Heard ‘Round the World” home run in 1951—the lack of a bathroom proved particularly problematic and downright embarrassing during one doubleheader at the Polo Grounds. According to legend, Hodges needed to relieve himself but couldn’t stray too far away to the nearest bathroom, which wasn’t very near. So he had to settle for using an empty cup as improvisation, resting it on the floor alongside his feet. Hodges was soon startled to see a colleague grab the cup and, believing it was beer, drink from it. The man’s reaction to the first sip was so sudden and violent, the contents spilled upon fans seated in the field level below. When officials came up for an explanation, Hodges told them, don’t worry—it’s only ‘used’ beer.

The New York Yankees walk from the Polo Grounds clubhouse down onto the playing field in the deepest portion of center field before the 1951 World Series. After the game, players had to walk—and sometimes run—back to the clubhouse some 500 feet away from the dugout while avoiding memorabilia-hungry fans who were allowed on the field. (The Rucker Archive)

The Meal Ticket and the Ott Spot.

On the field, the Giants remained a consistent contending force in the National League but lost its edge of superiority, especially after an aging and ailing John McGraw stepped down and ended his 30-year managerial reign in 1932. But two future Hall of Famers kept the championship fire alight, winning three more pennants within a decade—including another world title in 1933.

Screwball southpaw Carl Hubbell quietly went about his business on the mound and evolved into the greatest New York Giants pitcher this side of Christy Mathewson. During his prime in the mid-1930s, Hubbell won 20 or more games five straight times, won three ERA titles—including a scintillating 1.66 mark in 1933 that was the NL’s lowest over a 51-year period between 1917 and 1968—once threw an 18-inning shutout (walking none) and, over a two-year period from 1936-37, won 24 straight games to set a major league record which still stands. Hubbell loved the Polo Grounds, consistently posting a lower ERA (often, much lower) at home than on the road.

Hubbell’s partner in crime on the hitting side was Mel Ott, who debuted with the Giants in 1926 just a month after turning 17; at age 20, he batted .328 with 42 homers and 151 RBIs. Wielding a high frontal leg kick just before swinging away, the left-handed hitting Ott would lead the NL six times in home runs, become the all-time leader among National Leaguers in long balls before the time of Mays and Aaron, and was #1 on the all-time list among hitters at the Polo Grounds, with 323 of his 511 career blasts deposited there. The later his career went, the more he fancied hitting down the right-field line; of his final 96 home runs, 81 of them were hit at the Grounds. In 1943, all 18 of his homers would be hit at the ballpark.

Beginning of the End.

Support for the Giants appeared stronger than ever at the end of World War II, with Polo Grounds attendance hitting its all-time high of 1.6 million in 1947. This was all the more notable given how the franchise staggered through the 1940s with uneven results and little noise at the top of the standings. But just when the Giants began to steadily improve into the 1950s, ticket sales began a disturbing downward trend. Even in 1951, when the Giants won their first flag in 14 years, they only managed to click past a million thanks to the additional two home games needed to decide the pennant—the last ending on Bobby Thomson’s legendary walk-off home run belted into the upper deck behind left field.

Dusty Rhodes rounds first after hitting his walk-off “chip shot” home run down the short right-field line—measuring just 257 feet away from home plate—in Game One of the 1954 World Series. The three-run blast defeated the Cleveland Indians in 10 innings, 5-2. (The Sporting News Archives)

The Giants had made some noise in the 1940s in regards to redevelopment around the Polo Grounds, but the dwindling gate and Doyle death likely put a stop to that—with more of the focus shifted on getting out of Harlem. It didn’t matter that the Giants had become a NL power once again in the 1950s, or that the rise of the Brooklyn Dodgers had intensified their rivalry, or that the Giants had snared an all-time great talent in Willie Mays, who after a long day at the ballpark maintained the enthusiasm and energy to walk up the John T. Brush Stairway on Coogan’s Bluff and play stickball with kids on the streets of Harlem. All that mattered to the Giants was that fewer people overall were coming to the Polo Grounds. If anyone needed proof, all one needed to do was look at the 1956 attendance table and find that only the decrepit Washington Senators drew fewer fans among 16 major league teams than the Giants’ 629,000.

As early as 1953, the rumors had begun to swirl. One had the Giants moving across the Harlem and pay rent at Yankee Stadium. Another had them headed to Minneapolis. And of course, there was talk of a move to San Francisco. One by one, Horace Stoneham—bequeathed with ownership of the Giants by his father in 1936—shot them down. Meanwhile, the football Giants said they were done with the Polo Grounds and, after 1955, migrated to Yankee Stadium; New York City initiated a 5% “amusement tax” that further discouraged ticket buyers; and Robert Moses, the city’s “master builder,” was pressuring the Coogan estate (which owned the Polo Grounds land) to sell so he could build more hi-rise, low-income housing projects. The Polo Grounds’ future was slowly sinking, a la the Titanic.

The Giants were briefly in discussion with developers to build a massive, 110,000-seat stadium over railroad tracks on the west side of central Manhattan, along the Hudson River; they would even call it the Polo Grounds—because, why not. But the project, estimated as high as a then-staggering $80 million, quickly collapsed under its own ambitious weight. The final nail in the coffin for the Giants at the Polo Grounds—and New York in general—came when the Dodgers decided to act on their years-long wish to move to Los Angeles. The Giants, intrigued by what San Francisco had to offer and intent on preserving the longstanding Giants-Dodgers rivalry, decided to follow suit and pack for the West Coast as well. When Horace Stoneham faced the press following the announcement in the Summer of 1957, he made his reasoning as witty as he did blunt, stating that he felt bad for the kids of New York—but claimed he hadn’t been seeing many of their fathers at the Polo Grounds of late.

Before a crowd of 11,606 on September 29, 1957, the Giants played their final home game at the Polo Grounds. A parade of past franchise greats, including George Burns, Larry Doyle, Carl Hubbell and Rube Marquard, showed up to shed their tears in a pregame ceremony. The widow of John McGraw lamented the Giants’ departure, saying that “New York can never be the same to me.” The Giants lost to the Pittsburgh Pirates, 9-1, and then made one final sprint to the center-field clubhouse to avoid a mob of souvenir-seeking fans.

The Giants were gone in body from the Polo Grounds, but not in contractual spirit. They still owed over $100,000 a year in rent on the ballpark through 1962, so the team, under the corporate façade of the National Exhibition Company started way back in the 1920s, still looked to book the joint whenever possible. They succeeded with a number of events, many of them having nothing to do with sport. There were Catholic masses, a Billy Graham sermon, a mass group session held by Jehovah’s Witnesses, and a convention for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). Baseball threatened to make an early comeback as well; rumor had the Cincinnati Reds filling the void, but they were merely using the Polo Grounds as leverage to get better parking considerations back at Crosley Field.

A Laughable Coda.

Just when it seemed that the Polo Grounds would be knocked out for the count, they acquired two new tenants. One was a start-up football franchise in the American Football League’s New York Titans (known later as the Jets), who quickly realized that although the Giants continued to pay rent on the Grounds, they were spending next to nothing on upkeep. The seats had grown old and dirty, the ironwork had turned green, the press box facilities were barely adequate, and the field was something of a weed-strewn war zone. Titans owner Harry Wismer called it a “graveyard.”

The other new tenant wasn’t going to stand for the Polo Grounds as was. The expansion New York Mets originally wasn’t even going to play in the old ballyard, but Shea Stadium was taking much longer to complete than anticipated, while the Yankees said no to loaning out Yankee Stadium. The Mets spent $350,000 to spruce up the Grounds, but it was more cosmetic than reconstructive—like applying makeup to a corpse.

The inside was given a badly needed splash of green while the exterior was repainted in the Mets’ orange and blue colors, new lights were installed, the playing field was rejuvenated, the outfield walls were adorned with ads for the first time in 20 years and, finally for the first time, an electronic scoreboard was rigged up. Under the stands, a 400-seat lounge was created with a 60-foot-long bar. As the Mets dredged up an aging roster of former Giants and Dodgers stars for their inaugural 1962 campaign, Red Smith of the New York Herald Tribune opined that the lounge would come in handy. “Watching the Mets on the field may very well drive fans to drink,” he said.

The Mets, led by 72-yer-old Casey Stengel—who retained his acerbic charm as long as he was awake—were an embarrassing sensation from start to finish in their two seasons at the Polo Grounds. “Ace” pitcher Roger Craig won 15 games—and lost 46. Marv Throneberry, nicknamed “Marvelous” in jest by the fans, once legged out a triple but was ruled out because he failed to touch both first and second base on his way there. Jimmy Piersall, still crazy after all these years, celebrated his 100th career home run by running backward around the bases. (Unlike Throneberry, at least he touched them all.) The 1962 season saw a Polo Grounds-record 213 home runs hammered, 120 of them by the opposition. Two of those, by the Chicago Cubs’ Lou Brock and Milwaukee Braves’ Hank Aaron, were hit on consecutive days into the far-flung reaches of the center-field bleachers—matching the total number of such tape-measured shots in the previous 40 years. (The other two were hit by the Braves’ Joe Adcock in 1953 and Luke Easter in a 1948 Negro League contest.) “The Polo Grounds is a great park,” Stengel said. “It is built for every club but mine.”

Before moving into the far more modern Shea Stadium, the Mets were an awful 56-105 at the Polo Grounds. (It was even worse on the road, where they were 35-126.) But the fans loved them; the Mets provided a loose-knit alternative to the dull, uppity atmosphere across the Harlem at Yankee Stadium. The crowds were younger, vibrant and more diverse, almost as if they were transplanted from a movie matinee. The joint was particularly jumping when the San Francisco Giants and Los Angeles Dodgers arrived for their first appearances in New York since leaving to go west. In 1962, the Mets drew more fans (473,000) for 18 games against the Giants and Dodgers than for the other 62 home dates. Overall, the 922,000 admissions in 1962 set a record for a last-place team—a record the Mets would reset in 1963, when they pulled in 1.08 million.

The Mets bid adieu to the Grounds on September 18, 1963 before a gathering of 1,752—or roughly one fan for every housing unit that would be built in the ballpark’s place. Naturally, the Mets lost, 5-1 to the Phillies—ending the game by hitting into a double play.

There would be one more baseball game played at the Polo Grounds with a more respectable aura. A Latin All-Star game featuring some of the game’s greats of the day—including Roberto Clemente, Juan Marichal and Orlando Cepeda—was played in front of 14,235 spectators. The very last sporting match at the Grounds took place two months later, when the Jets lost to the Buffalo Bills in an AFL game, 19-10, before only 6,526 fans. That left one last event: Demolition. It began on April 10, 1964, using the same wrecking ball employed to tear down Brooklyn’s Ebbets Field.

Pieces of the Polo Grounds went here, there and everywhere. Over 3,000 of its seats were moved to Yonkers Raceway, a horse racing facility; others are occasionally sold on online auction sites, with aisle seats outfitted with the “NY” insignia remaining the more popular (and expensive) item. A number of the light poles were shifted to Phoenix’ Municipal Stadium, where the Giants briefly held spring training. Three square feet of the Polo Grounds’ turf was cut out and airmailed to San Francisco following the Giants’ last game in New York, to be inserted into Seals Stadium, but it got lost in transit; it took nearly a month for the airline to locate it in Lost and Found. An even biggest mystery was the whereabouts of the Eddie Grant memorial; in the manic rush of fans to grab anything they could after the Giants’ Polo Grounds finale, someone had the tools (and the strength) to pry it from the ground and run off with it. It remained ‘missing’ until 1999 when it was discovered in the attic of a New Jersey home. The memorial is now property of the offbeat Baseball Reliquary museum based in Los Angeles.

The Polo Grounds lacked class and formality, absent of the palatial entrance that graced other ballparks of its time; you either took a deep set of stairs down from the Speedway to get in on the home plate side, or you stepped off the elevated train and ramped your way into the bleachers. But there certainly was no shortage of history, as the Grounds was home to some of the greatest legends ever seen and some of the most indelible moments ever written in the chronicles of baseball.

The Ballparks: Oracle Park In the annals of baseball, home runs have landed in places as varied as apartments, auto dealerships and snowbanks. But hardly ever into water. Oracle Park, with its glorious views of San Francisco Bay, has become the first park in the majors to allow a crushing drive to make a splash landing, past the slim right-field bleachers and into aptly-named McCovey Cove—where a potpourri of aquatic adventurists anxiously await their chance to scoop up a souvenir.

The Ballparks: Oracle Park In the annals of baseball, home runs have landed in places as varied as apartments, auto dealerships and snowbanks. But hardly ever into water. Oracle Park, with its glorious views of San Francisco Bay, has become the first park in the majors to allow a crushing drive to make a splash landing, past the slim right-field bleachers and into aptly-named McCovey Cove—where a potpourri of aquatic adventurists anxiously await their chance to scoop up a souvenir.

The Ballparks: Shea Stadium Never mind the jet packs and monorails. Shea Stadium represented the Space Age to New Yorkers freed of their rotting baseball relics of yesteryear, proudly serving as the center of the Gotham entertainment universe until early neglect threatened to turn it into a black hole. Good times or bad, you could always count on a high-decibel din courtesy of diehard Mets fans and the airliners roaring overhead.

The Ballparks: Shea Stadium Never mind the jet packs and monorails. Shea Stadium represented the Space Age to New Yorkers freed of their rotting baseball relics of yesteryear, proudly serving as the center of the Gotham entertainment universe until early neglect threatened to turn it into a black hole. Good times or bad, you could always count on a high-decibel din courtesy of diehard Mets fans and the airliners roaring overhead.

The Ballparks: Yankee Stadium The House that Ruth Built and Mayor Lindsay Rebuilt, the majestic cathedral otherwise known simply as the Stadium was the last and grandest addition to baseball’s romantic steel-and-concrete era, a towering achievement which emitted a confident aura to its colossal frame. It was the perfect match for a proud and iconic franchise that forever tolerated anything short of a World Series title as pure dishonor.

The Ballparks: Yankee Stadium The House that Ruth Built and Mayor Lindsay Rebuilt, the majestic cathedral otherwise known simply as the Stadium was the last and grandest addition to baseball’s romantic steel-and-concrete era, a towering achievement which emitted a confident aura to its colossal frame. It was the perfect match for a proud and iconic franchise that forever tolerated anything short of a World Series title as pure dishonor.