The Ballparks

Shea Stadium

Queens, New York

Never mind the jet packs and monorails. Shea Stadium represented the Space Age to New Yorkers freed of their rotting baseball relics of yesteryear, proudly serving as the center of the Gotham entertainment universe until early neglect threatened to turn it into a black hole. Good times or bad, you could always count on a high-decibel din courtesy of diehard Mets fans and the airliners roaring overhead.

The noise. That’s what a lot of people remember most about Shea Stadium over its 45-year lifespan. The Beatles certainly remember it. The screaming fans, 60,000 of them, were so loud that the Fab Four couldn’t even hear their own instruments. The suave, self-assured quarterback Joe Namath brought out the ladies as well, adding to the surge of sound whenever the football Jets took to the Shea turf. And then there were those other jets, taking off from nearby La Guardia International Airport and buzzing Shea as they almost always seemed to do when the stadium’s main attraction, the New York Mets, came out of the dugout to play a brand of ball that ranged from amazing to miraculous to just plain dreadful.

The Mets and their faithful, some of the craziest baseball fans you’d ever run across, witnessed all sorts of objects fly within the airspace of Shea Stadium—very few of them being fly balls that seldom went deep off the bats of an occasionally tin Mets offense. The airliners kept a safe distance—most of the time. One mistook the outfield light towers for La Guardia landing lights and buzzed the stadium by a reported 1,000 feet, though players warming up for a game swear it was much closer than that. There was the day the Goodyear blimp, covering the U.S. Open tennis tournament nearby, decided to take a joyride over Shea, casting an ominous shadow over the field and frightening players and fans into thinking they were about to relive Black Sunday. And there was the flying saucer based at the adjacent World’s Fair—it never was an observation tower, folks—that sprang loose and caught the eye of awed Mets outfielder Lance Johnson as recalled in Men in Black. Only one aerial object ever crashed into Shea; a remote-controlled toy plane that lost control and flew into a section of football fans—one of whom was killed—during halftime of a 1979 Jets game.

When it opened in 1964, Shea Stadium was hailed as the future of modern stadiums. Sadly, the optimism was proven right. The semi-circular, multi-purpose facility helped ignite the Cookie Cutter Monster movement that would rule the next 25 years of American stadia, providing a compromised, municipally funded comfort level that left fans sitting more far than near to the action.

Yet at first, Shea Stadium was hugely embraced by New Yorkers. And for good reason. Ebbets Field had been torn down. The Polo Grounds was rotting toward a similar fate. The original Yankee Stadium remained in use—but its aging edifice, lacquered with a tiring coat of snobbery, turned anyone not obsessed with pinstripes completely off.

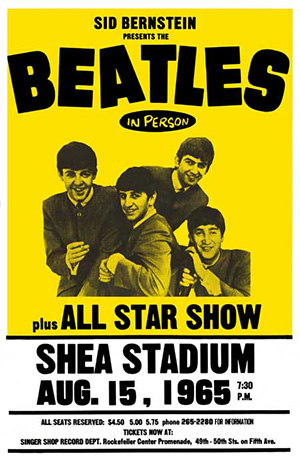

With all due respect to Madison Square Garden, Shea Stadium was the place to be within Gotham over its first five years. There was, of course, the Beatles, whose summer date with Shea in 1965 gave birth to stadium rock. There was, of course, Namath and his Jets, who captivated the sports world with a stunning Super Bowl triumph in 1969. And there was, of course, the Mets, a hapless-to-date ballclub who, nine months after the Jets’ shocking upset of the mighty Baltimore Colts, doubled down and performed their out-of-nowhere miracle magic in the World Series against the mighty Baltimore Orioles.

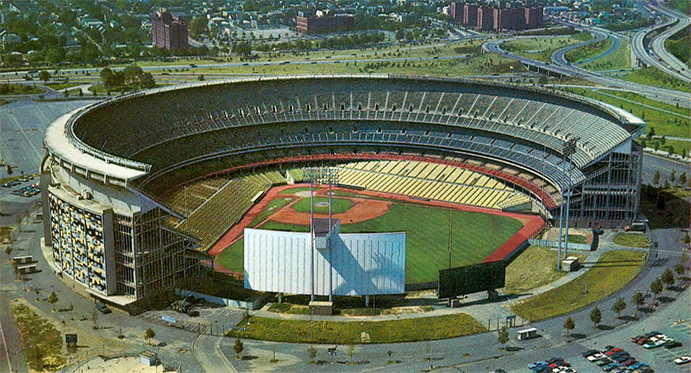

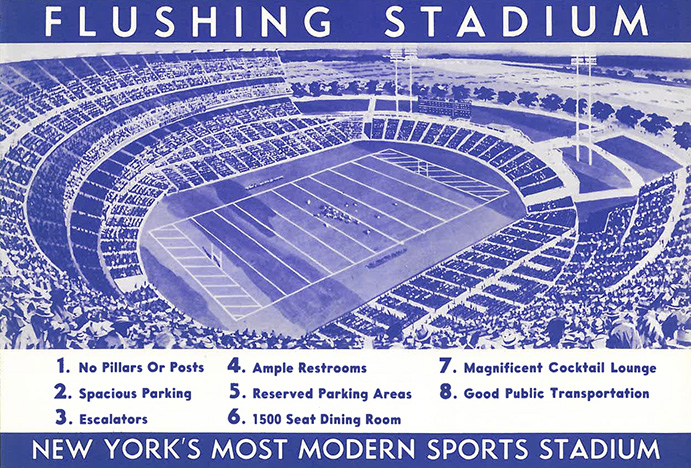

An early rendition of Shea Stadium in its football formation. Note the single-decked bleachers, which was not a part of the final, original build.

From Shame to Shea.

The irony of Shea Stadium is that it was originally conceived as the new home for the Brooklyn Dodgers. That was back in the mid-1950s, when New York politicians panicked amid rampant rumors that the Boys of Summer were California-bound. When Walter O’Malley, Dodgers owner and baseball’s Lord of Flatbush, was offered the site at Flushing Meadows—a marshy expanse of land that sliced through the heart of Queens, eight miles to the north—he declined, saying it made no sense for a Brooklyn team to play in Queens. O’Malley’s comment sounded loyal to Brooklynites in its context, which to them made it all the more maddening when he darted off to Los Angeles with the Dodgers.

The loss of the Dodgers and the New York Giants—who were also offered the stadium site—to the West Coast took an enormous bite out of the Big Apple of baseball and left local authorities scrambling. Mayor Robert Wagner set up a four-man committee dedicated to returning National League baseball to New York; heading up the group was prominent lawyer William Shea, once described by New York magazine as a “roomful of a man,” a powerful and efficient multitasker and who once was listed alongside O’Malley on the Dodgers’ org chart—before the latter was promoted to the top and began his mechanizations to move the franchise west. Infuriation with his former colleague only gave Shea added incentive to acquire a team for the city’s proposed stadium.

Having seen the Dodgers and Giants stolen away, Shea wanted to steal back; it was his only option, given that major league expansion wasn’t on the table. He phoned the Cincinnati Reds, Pittsburgh Pirates and Philadelphia Phillies and asked if they were happy playing in aging facilities with little or no parking. They all said yes. NL president Warren Giles certainly seemed happy himself with the status quo, rubbing salt into Gotham’s wounds and publicly pronouncing, “Who needs New York?” Across town, the Yankees—highly content with their baseball monopoly within New York—dissed the Flushing Meadows site, with co-owner Dan Topping telling The Sporting News: “Sponsoring a new club housed on the Meadow would be a great way to go broke.”

Flat out of both options and patience, Shea went on the offensive. Late in 1958, he announced that if the National League didn’t want to return to New York, he’d start his own league, a third circuit called the Continental League that would tap into a list of emerging postwar cities itching for major league action; Toronto, Buffalo, Denver, Houston were among those with investors ready to get on board. The established two leagues yawned, even after Shea hinted that he had a notable “mystery” baseman man on his side with organizational and political clout. When that man was revealed as Branch Rickey—father of the modern farm system, emancipator of the game and rescuer of struggling franchises in St. Louis, Brooklyn and Pittsburgh—perspiration began to show on the faces of major league execs. The sweat intensified when Rickey went to Washington and started chatting with prominent U.S. Congressmen about abolishing baseball’s antitrust exemption.

The double-barreled threat of the Continental League and Congress proved too much for baseball to ignore, forcing the game to accept expansion for the first time. Undoubtedly, New York would be on that short list, but the NL pointed a stern finger at Shea and the city demanding that they better have a new facility ready. Shea pointed his own finger at a map of Flushing Meadows and replied that, boy, do we have a ballpark site for you.

Tomorrowland, Today.

The location of Flushing Meadows Stadium, as Shea Stadium was originally named, was ideal if not romantic—easily approachable for those driving from New York’s outlying boroughs, so long as the traffic from parkways and freeways that surrounded the site didn’t become a clogged nightmare, which it often did. The swampy area-turned-landfill nicknamed the Valley of the Ashes provided a good chunk of acreage for the 1939 World’s Fair, a popular exposition whose promise of the “Dawn of a New Day” was shattered on the eve of the Axis’ temporary wrecking of the world. As designs for the new stadium were being drawn up, so were those for a new World’s Fair next door, one that would promote “Peace Through Understanding,” as hope for progress toward an optimistic future.

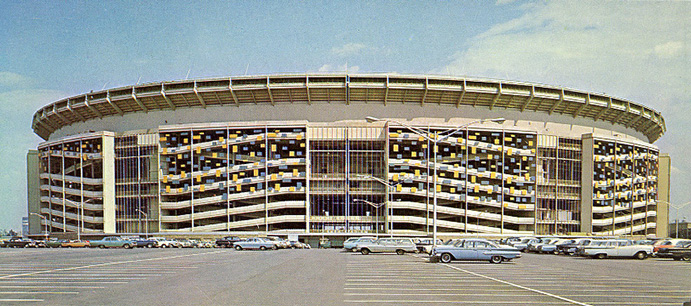

The original façade to Shea Stadium, embellished by a series of orange and blue panels randomly decorating the spectator switchback ramps.

The new stadium was to be a reflection of that progress, a modern convenience New Yorkers were starving for at a time when the city was growing more old, rust-ridden and mean. Improved freeways would ferry fans in faster. A sea of parking would allow for easier auto access. Escalators, a touched-on novelty at a few other new stadiums, would be located everywhere and quickly get people to their seats, no matter how far from the gate. Mercury vapor lamps would light up the venue. Compared to the dusty, aging relics of Yankee Stadium, Ebbets Field and the Polo Grounds, Shea would be Tomorrowland.

William Shea wanted to take the modernity a few steps further. He envisioned a massive, enclosed stadium with 100,000 seats and a retractable dome, but even he couldn’t coax the extra money to make it all work. And besides, the New York Mets, newly born in 1960, weren’t too keen on Shea’s grand ambitions. With their urging, the project was ultimately scaled back to an open-air, partially open stadium with no seating whatsoever behind the outfield fences to give it breathing room and the feel of a ballpark, not a coliseum. An understanding Shea spun, “New York fans are entitled to fresh air,” even if it was some of baseball’s iciest and meanest winds outside of Candlestick Park as Mets fans would eventually discover during early and late season games.

Just getting the building, however it was going to look, up and running proved to be an exercise in avoiding gray hair and frayed nerves. The first shovels were held back from hitting the ground in early 1961 when the New York State Assembly surprisingly refused to okay the funds to build the stadium. A startled Mayor Wagner, along with Assemblyman Anthony P. Savarese, the bill’s sponsor, started talking to the naysayers; the two must have promised them a free trip to Shangri-La, as 40 lawmakers changed their minds the next day, took a second, more successful vote and cleared the biggest financial hurdle for the stadium.

The construction stage proved to be even less of a picnic. Two subcontractors went bankrupt. Faulty construction was discovered. Poor access roads bogged down the trucks hauling in materials. Labor stoppages—17 in all—led to many stops and starts. Even Mother Nature wasn’t forgiving; unusually cold winter weather slowed things down.

The Mets were originally hoping to move in and begin play at the new stadium for their inaugural 1962 season, but the 1962 deadline became a 1963 deadline, which became a 1964 deadline. The Yankees said no to sharing Yankee Stadium in the interim, so the Mets had no choice but to blow the dust off the Polo Grounds, unused by the majors for five years.

Complementing the Fair.

Intensive work continued right up to Opening Day, but smiles were abundant. Shea “christened” in the stadium by taking two bottles of water—one from the Harlem River near the Polo Grounds, the other from the Gowanus Canal near torn-down Ebbets Field—and poured it on the playing field, the last rolls of which were still being laid down while players took batting practice. No word on whether the Gowanus water—legendary for its stifling toxicity—killed the grass.

A healthy look upwards at Shea Stadium’s many levels, including (at bottom) the field level which swiveled on a track to conform to either baseball or football. (Flickr—Gary Dunaier)

Shea Stadium, gracefully standing out amid the Flushing Meadows panorama, opened a week before the 1964 World’s Fair; it would, at the time, hold its own as a worthy complement to the architectural splendor next door.

On the outside, a series of equally spaced switchback ramps stuck out from the main structure and created a wavy pattern that gave the structure a harmonic flow of concrete; the ramp structures were randomly shaded by rectangular metal panels—half of them orange, the other half blue—that clanged in the wind and appeared from a distance like chads spit out of an IBM punch card. Topping it all was the crown-like recessing of the upper deck that overhung the main structure wall at an angle, an external feature made all the more sleek by the absence of light towers with most of the lamps embedded within the rim of the upper roof.

Within the bowl, Shea Stadium rose upward with five levels of seating (if you include the press balcony); the lowest level consisted of two arch-shaped sections of field boxes that moved on tracks below to be properly positioned for either baseball or football, with seats at the top the arc kissing the loge level above. The vast majority of seating was positioned between the foul poles, which might make for great promotional fodder aimed at the anti-bleacher crowd, but the truth is there was a great deal of nosebleed views to be filled in the voluminous (and steep) upper deck. Also, all seats—which, in antiquated fashion, were wooden—were aimed at the center of the field; maybe that was wonderful to watch a coin toss before a Jets game, but the bulk of a baseball game takes place between home plate and the pitching mound, not short center field.

The lack of bleacher seats also allowed optimal viewing of the main right-field scoreboard, a massive display of information spanning 175 feet wide and 86 feet tall, topped by an 18’x24’ rear projection screen—essentially, a giant, old-fashioned TV. Compared with today’s hi-def assault of visual noise at today’s ballparks, the Shea video screen was quite crude—it was essentially of no use during the day as the sun neutered its weak range of brightness—but in the 1960s, it was quite novel.

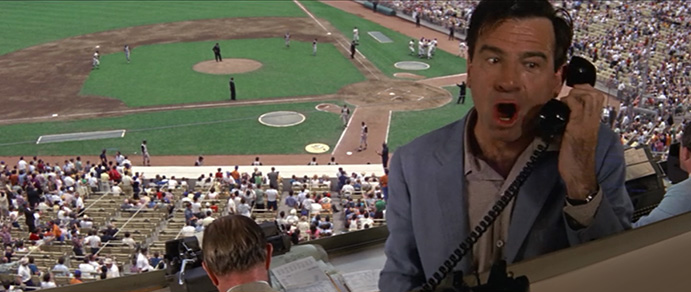

Fictional New York sportswriter Oscar Madison (Walter Matthau) takes out his anger on roommate Felix Unger after missing a triple play at Shea Stadium in The Odd Couple. The scene was filmed just prior to an actual game between the Pirates and Mets. (Warner Brothers)

Matinee Crowds, Serial Losers.

Even though the subway conveniently stopped nearby, it seemed everyone decided to take the car to Shea Stadium for its inaugural 1964 contest as parking lots overflowed and spilled into the adjacent Iron Triangle, a slum of auto parts shops and junkyards that remained a neighborly eyesore throughout Shea’s long lifespan. Despite the transportation headaches, the reviews were glowing for a stadium even as the Amazin’ Mets—all sarcasm intended— lost on cue, 4-3 to the Pittsburgh Pirates. The New York Daily News’ Dick Young asked and answered: “You take a shabby downtrodden bunch of Mets, and you wrap them in a spanking new ballpark that cost somebody $25 million bucks and what have you got? A shabby, downtrodden bunch of Mets, still losing…thereby christening Shea Stadium with tears of defeat.”

Other writers got a little carried away in their praise of Shea. The Sporting News’ Carl Lundquist, for one, bragged about the facility’s “elegance” to the point that it should be referred to as “Chez Stadium.” Regardless, the opening of Shea brought relief to local baseball fans who tired of carefully tip-toeing through deteriorating inner-city neighborhoods to watch major league ball in deteriorating ballparks.

Baseball’s leadoff season at Shea was full of memorable moments. At the end of May—and perhaps into early June—the second game of a doubleheader between the Mets and the San Francisco Giants lasted 23 innings and a NL-record seven hours and 23 minutes, a marathon showdown recalled (among other things) for being the first game in which Giants pitcher Gaylord Perry used his infamous spitter. Three weeks later, another future Hall of Famer, Jim Bunning, came to town with the Philadelphia Phillies and tossed the NL’s first perfect game in 84 years. The Mets naturally lost both of those games, but it was on the winning side—with a ton of help—when it hosted what would be the only All-Star Game in Shea history, with the NL scoring four times in the bottom of the ninth to win, 7-4. No Mets were involved in the making of that rally.

As expected, Shea would not immediately turn the fortunes of the Mets toward a positive direction; in fact, the team would log losing home records in each of its first five years at the new stadium. But the fans didn’t care. Young and old—many of them seemed to act like the former—they streamed into Shea like kids let loose at a movie theater to view a couple of crummy matinees; it didn’t matter that the Mets sucked, it was their palace to take over and cut loose. And cut loose they did, in big numbers, giving Shea Stadium its “raucous soul” as author and long-time Mets fan Dana Brand once wrote.

The New York skyline, an extended take on the Mets’ logo, replaced the original giant TV that sat atop the enormous right-field scoreboard. The ribbon at left covers the outline of the World Trade Center as a memorial to the twin buildings brought down during the 9-11 terrorist attack. (Flickr—Gary Dunaier)

Mets fans were loud, boisterous and, in the classic New York tradition, never afraid to express their opinions. Banners were one way to get their voices heard, and many were brought in; the Mets were okay with it, even occasionally holding Banner Day at Shea—in stark contrast to the no-banner policy nearby at buttoned-up Yankee Stadium. From this crowd came Karl Ehrhardt, the “Sign Man” who fashioned a whole cache of pre-printed messages in big bold letters and proudly held them up in the air—he always seemed to have the right message for the right moment—from his field-level seat.

A poster for the Shea Stadium concert that elevated stadium rock to the big leagues: The Beatles’ 1965 show in front off 55,000 screaming fans.

For sheer character, Mets fans were probably more wild and crazy than those who showed up at Shea for the many rock concerts that took place there. And that’s saying something.

The Beatles, of course, kicked things off with their legendary 1965 gig at Shea—the first ever performed at a major outdoor sports facility. Here’s just how nuts it was to have 55,000 people watch the lads from Liverpool; when Elvis Presley was the rage in 1957, the most he ever drew to any one concert was 16,000. The Beatles, and Shea, defined modern stadium rock.

Rock music at Shea reached high times, figuratively and perhaps chemically for the crowds, during the early 1980s. A riveting 1982 gig featured The Who on their first farewell tour—with punk rock pioneers The Clash as the opening act. A year later, The Police played in what lead man Sting recalled as the high point of their career—and yet, they were nearly overshadowed on the day by a then-obscure first act from Georgia called REM.

The Miracle Light…And Then, Darkness.

The Mets worried that as the new stadium smell wore off and the team continued to lose, attendance would wane. But the first, futile five years of the Mets at Shea Stadium would be followed by the next five, a period bookended by the franchise’s first two pennants. There was, of course, the Miracle—some would say inexplicable—1969 team that came out of nowhere to win 100 games, the NL flag and the World Series over the high-powered Orioles. Great defense (particularly by outfielders Ron Swoboda and Cleon Jones) would benefit the Mets much the same way bad defense (Bill Buckner) would benefit them 17 years later during their second championship run, but excellent pitching would be king of these times; ace Tom Seaver emerged as the epitome of a new kind of Met, one who didn’t find losing funny as original manager Casey Stengel might have thought. Seaver was also very, very good, and a huge fan favorite; nobody won more games (104, against just 57 losses) and accrued more strikeouts (1,370) at Shea than Tom Terrific.

The energetic fans who followed the Mets into the 1970s went into emotional overload in response to the sudden winning; they did a fair deal of damage to the stadium after the 1969 triumph, and they nearly rioted during the 1973 NLCS after long-time Mets favorite Bud Harrelson got into a violent dust-up at second with Cincinnati star Pete Rose; it took a delegation of Mets stars (including Seaver and Willie Mays, back in New York for his career twilight) to approach the faithful and calm them down.

Shea was at its busiest in the mid-1970s when the Mets and Jets were joined by the Yankees and football Giants, both of whom were in need of a temporary home while Yankee Stadium received a makeover. The Yankees were not always gracious guests; before one contest in 1975, a pregame military tribute included a 21-gun salute that accidentally knocked down part of the center field wall. Later in the season, Yankee outfielder Elliott Maddox sued everyone in sight after hurting his knee on a Shea turf beaten up from everyday use between April and October. The case remained open for 10 years until Maddox finally lost. (Ironically, Maddox played the final three seasons of his career…for the Mets.)

In the late 1970s, as New York City spiraled toward bankruptcy and the surviving remnants of the Mets’ original ownership group refused to accept baseball’s new era of free agency, Shea Stadium descended into its darkest days. It got especially dark when the infamous New York blackout in the summer of 1977 put a halt to a Mets-Cubs game. The city had little if any money to provide upkeep of Shea, while the Mets had little inclination to spruce it up. M. Donald Grant, the Mets’ chairman, seemed less interested in winning and more interested in angering the fan base—most especially when he traded Seaver in a 1977 move that generated the need for a bodyguard by his side while moving around Shea. Before long, there weren’t too many fans to worry about bumping into; by 1979, attendance reached under a million for the first and only time at Shea (the strike-shortened 1981 campaign excluded). Even Karl Ehrhardt, the Sign Man, stopped coming to Shea after Mets security gradually grew more hostile at some of the less flattering banners.

Compounding the Mets’ woes was that the Yankees, playing at renovated Yankee Stadium, had reclaimed their glory and recaptured the hearts of New York baseball fans under the turbulent but rewarding ownership of George Steinbrenner—who unlike the Mets took advantage of free agency and were winning as a result of it.

An excess of access: A jumble of ramps and escalators crisscross through Shea Stadium’s concourse, often referred to as dark and depressing—especially in its later years. (Flickr—Gary Dunaier)

A New Doubleday at Shea.

To the rescue in 1980 came new ownership, and not a moment too soon. A turnaround on the field would take its time, but the new regime—led by Nelson Doubleday, a descendent of disputed baseball inventor Abner Doubleday—didn’t waste any time giving Shea an aesthetic upgrade. The wooden seats were replaced with plastic ones. The pastels and grays were painted over with brighter hues, principally orange and blue from the Mets’ brand palette. Bleachers were added behind left field, and panache was added behind center as the Mets debuted the “Big Apple” structure, in which a giant red apple with a Mets logo rose from a black top hat—many thought it was a giant pot—whenever a New York player went deep.

In the decade to follow, more alterations were made; 50 luxury boxes were added, the faded “chad” panels adorning the outside ramps were removed and the portion of the facades in between the pedestrian ramps—which had exposed the concourses with vertical poles that looked like prison bars from afar—were completely covered with deep blue paneling decorated with giant multi-colored abstracts of ballplayers lit by neon. The giant scoreboard was updated, with the tube TV long gone—replaced with a more detailed variation of the illustrated New York City skyline used in the Mets’ logo. One modification was ultimately made to the skyline when, after 9-11, a memorial ribbon was placed over the outline of the World Trade Center.

Throughout Shea Stadium’s long existence, the playing field and its fair, symmetrical dimensions never changed. The outfield wall went through some modifications, not including those forged by the 21-gun salute in 1975. The original 12 feet of brick created confusion because it was topped by four feet of wire fencing—which, if hit on the fly, was deemed a home run per the ground rules. (This begged the question: Why put the wire there in the first place?) An orange line was painted atop the bricks in an attempt to give the wall procedural clarity, but that didn’t work. Finally in 1979, an inner eight-foot wooden fence was placed in front of the original wall, reducing dimensions by three feet across the field.

Still Crazy After All These Years.

Under Doubleday and his successor, Fred Wilpon (who went in with Doubleday as a 1% minority investor), the vibe so badly missing since the height of the Seaver Era gradually returned to Shea Stadium. The fans, back in record numbers, were still crazy after all these years—and they wrapped themselves around a new breed of Mets players who might have been even crazier. On and off the field, the Mets’ rosters of the 1980s and 1990s seemed tailor made for salivating headline writers at the New York Post.

Looking at the left-field corner of Shea Stadium, with a photographic mural of the 1986 champion Mets that didn’t stand the test of time very well. Also note, at lower right, the left-field bleachers, introduced to Shea in 1980. (Flickr—Gary Dunaier)

There was the 1986 championship team, which seemed to relish every opportunity to physically take on an opponent. There was David Cone, a 20-game winner who inspired Mets fans to wear “Coneheads” and was notorious for performing a different kind of warm-up in the Shea bullpen within the presence of a young woman. There was Keith Hernandez and Darryl Strawberry, who got violent with each other while posing for the team photo. There was class clown reliever Roger McDowell, who fictionally spat the Magic Loogie at Seinfeld’s Cosmo Kramer and Newman the Mailman in the Shea parking lot after they harassed Hernandez for a costly error. And there was, sadly, Hall-of-Fame careers derailed when Mets phenoms Strawberry—whose 127 homers at Shea were the most hit by any one player—and pitcher Dwight Gooden descended into drugs and other unwanted chaos.

There were even moments to satisfy those masochistically yearning for Casey Stengel’s “Amazin” days of yore. Hard-luck pitcher Anthony Young lost a major league-record 27 straight decisions, while catcher Mackey Sasser struggled to make a simple return throw to the pitcher.

Among the updates made to Shea Stadium in the 1980s was the introduction of giant neon-lit baseball figures, covering up the areas in between the spectator switchback ramps. (Flickr—Tweber1)

Other opponents simply let their bats and arms do the talking—and there was little Mets fans could do but shake their fists at them in frustration. Say “Chipper Jones” to Mets fans, for instance, and you’ll likely be met with an angry gnashing of teeth. The Atlanta infielder so enjoyed playing at Shea (where he hit .313 with 19 homers in 88 games) that he named his third child Shea. But Jones was hardly the most potent visitor at Shea. Among those who fared much better were a couple of San Diego Padres, Gene Richards and Hall of Famer Dave Winfield, who respectively hit .389 and .385 for the two highest averages among non-Mets with 100-plus at-bats. And not only did Willie Stargell hit the first-ever home run at Shea, he hit more than any other visitor with 26—except Mike Schmidt, who in later years would tie him.

As Shea Stadium’s life wound down and its replacement, Citi Field, rose beyond the outfield for all to see, Mets fans packed the joint as never before, as if they knew they were going to miss the place when it was gone. In Shea’s final season of 2008, the fans practically maxed out the 55,000-seat capacity for every game—leading to a franchise-record four million fans, making the Mets the second (and last to date) NL team to do so. The Mets weren’t the only folks packing them in that year: A final concert, entitled “The Last Play at Shea,” featured an all-star cast of legends and rockers (not John Rocker) that included ex-Beatle Paul McCartney, Billy Joel, Tony Bennett, the Who’s Roger Daltrey and Garth Brooks.

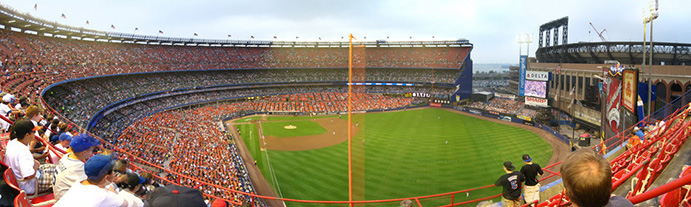

A panorama of Shea Stadium from the upper deck behind the right-field foul pole. To the right, Citi Field—Shea’s replacement—takes shape. (Flickr—Rudi Riet)

The Mets’ own last game at Shea was bittersweet in more ways than one, as for the second straight year they lost to the Florida Marlins to knock themselves out of playoff contention on the very last day of the regular season. Overall, the Mets won more games (1,859) than they lost (1,713) at Shea and averaged 26,500 per game, well above the major league average for the same period. Despite all that great pitching, the Mets never threw a no-hitter at Shea (nor anywhere else, for that matter), but they did perform five triple plays—one of those missed by Odd Couple sportswriter Oscar Madison when he had to take a call from roommate Felix Unger warning him not to eat frankfurters at the ballpark, because he’d be making them for dinner.

While many stadiums from the era of multi-purpose monstrosity are quickly scorned like the big, outdated tube TV discarded to the front sidewalk with “Free” taped to its side, Shea Stadium seems to be the one exception, one that remains cherished in the minds of Mets fans in spite of its drawbacks. Citi Field, the Mets’ current home, is nice and modern and contains all the expected bells and whistles, but it just hasn’t seemed to catch on with fans who see it as soullessly corporate. (That the Mets posted losing records in each of their first six years there didn’t help.)

Maybe, in time, Citi Field will catch up and match Shea, emotion for emotion.

But it has its work cut out.

The Ballparks: The Polo Grounds Peculiar doesn’t even begin to describe the Polo Grounds, a bathtub of a ballpark that yielded pop fly home runs and tape-measure outs as it led almost as many lives as a cat against the rocky bluffs of Harlem. Through its resiliency, it manifested more than its share of baseball’s legendary moments and unforgettable actors, whether it was McGraw, Mathewson, Merkle, Master Melvin, Mays or, yes, even Marvelous Marv.

The Ballparks: The Polo Grounds Peculiar doesn’t even begin to describe the Polo Grounds, a bathtub of a ballpark that yielded pop fly home runs and tape-measure outs as it led almost as many lives as a cat against the rocky bluffs of Harlem. Through its resiliency, it manifested more than its share of baseball’s legendary moments and unforgettable actors, whether it was McGraw, Mathewson, Merkle, Master Melvin, Mays or, yes, even Marvelous Marv.

The Ballparks: Citi Field An owner known more for his dubious Wall Street ties than his nostalgic Brooklyn upbringing built a ballpark that shouts Ebbets Field up front, steel bridge trusses in the back and the ongoing soap opera that is the New York Mets in the center, providing head-shaking theater no matter how much they brought in the fences to generate artificial offense. But as long as the Shake Shack remains open, Mets fans will better accept Citi Field for the inharmonious ballpark that it is.

The Ballparks: Citi Field An owner known more for his dubious Wall Street ties than his nostalgic Brooklyn upbringing built a ballpark that shouts Ebbets Field up front, steel bridge trusses in the back and the ongoing soap opera that is the New York Mets in the center, providing head-shaking theater no matter how much they brought in the fences to generate artificial offense. But as long as the Shake Shack remains open, Mets fans will better accept Citi Field for the inharmonious ballpark that it is.

New York Mets Team History A decade-by-decade history of the Mets, the ballparks they’ve played in, and the four people who are on the franchise’s Mount Rushmore.