THE BALLPARKS

Comerica Park

Detroit, Michigan

(Flickr—Kevin Ward)

For over 100 years, the crossroads of Cochrane and Michigan Avenues served as the cornerstone of Detroit baseball, with legendary names as Cobb, Greenberg, Kaline, McLain and Fidrych gracing famous episodes and careers upon Tiger Stadium. Now, closer to downtown, the Tigers’ new home at Comerica Park stands as a virtual modern museum for fans young and old—and a place where the ghosts of Tigers past can comfortably feel at home and watch the future take shape.

(iStock)

Had Piscine Patel, the title protagonist from Life of Pi, failed to get over his trauma of spending nine months in a lifeboat with a 300-pound tiger, then he would likely feel ill at ease walking around and about Comerica Park. Here, the tigers roam everywhere—and it’s not just the nine guys on the expansive ballfield wearing the familiar old English “D” upon the uniform of the Detroit Tigers.

The primary entrance, along the park’s first base side, is a tigerphobic’s nightmare in particular. The half-circular plaza is patrolled at its center by a 15-foot-tall white tiger sculpture, bearing down with its left claw aggressively extended toward pedestrians. Four smaller but no less menacing tigers prowl above the top of the surrounding buildings’ edges, looking eager to lend assistance. An escape down Witherell Street to the southwest entry, behind the right-field bleachers, provides little solace for the faint of feline-fearing heart as two more tigers stand guard above the ticketing gates, ready to pounce at any moment.

You might finally find tiger-free relief down Adams Avenue at the left-field bleacher entry, but to get there you walk past one tiger head after another, decorative busts equally spaced apart and sticking out of the outbuildings’ brick exteriors with claw marks etched into the concrete base below. If the more fearful among us could manage to breathe deep and make it through the turnstiles, they’d have to contend with tigers roaming the scoreboard, growling with eyes lit whenever the Tigers belt a home run, and a merry-go-round in which you get to hop on and ride—yes, you guessed it—more tigers. At some point you’d have to wonder if Comerica Park is a ballpark or a maulpark.

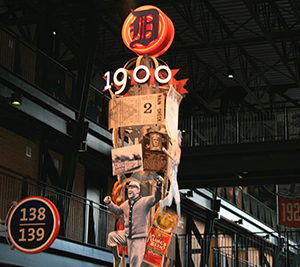

Beyond the tiger fetish and the numerous amusement rides on the venue’s north end that shout county fair as much as baseball, Comerica Park does mind the heritage of Detroit baseball—particularly with its predecessor, Tiger Stadium, even if that former park’s tight, claustrophobic environment is a stark contrast to Comerica’s reclined, more expansive (15 acres vs. nine) real estate. Perusing through the spacious main concourse is like taking a walk through time, with imaginative historical kiosks and a parade of sculptures honoring Tiger greats of the past, allowing fans to note that although Detroit baseball didn’t start with Comerica Park, it is allowed to thrive today because of the modern yard.

Mr. “I Will.”

The genesis of Comerica Park was born from the ashes of the effort to save Tiger Stadium. Fans had grown to love the old ballpark, built in 1912—but Tiger ownership didn’t share that love. Domino’s Pizza founder Tom Monaghan had bought the team in 1983 and initially said he would stay at Tiger Stadium, but changed his mind after realizing that sentimentality didn’t fill the cash vault.

Every idea Monaghan drew up for a new facility within Detroit was done so with a fortress mentality. His vision was not to invite the city environs in, as Oriole Park at Camden Yards would eventually do in Baltimore, but to create an inverted prison habitat—with law-abiding fans on the inside and the ‘prisoners’ outside the gates. Monaghan’s proposals, located in spots as varied as downtown and the middle of a lower-class neighborhood, rarely got anyone excited and went nowhere.

When city voters approved a ballot initiative to ban public investment for any new sports facility, Monaghan gave up. One pizza impresario sold to another as Little Caesar’s Mike Ilitch, who once upon a time played in the Tigers’ organization (he never made it out of the minors), bought the team in 1992 and gave Tiger Stadium his own shot of rejuvenation, replacing seats, installing food courts and drowning the place in advertisements. But he lost millions and came to the realization that there was only so much lipstick you could put on a pig—even a beloved one like Tiger Stadium. Like Monaghan before him, Ilitch knew that the only profitable future for the Tigers lay in a new ballpark.

Unlike the Monaghan regime, the flamboyant Ilitch embraced the idea of not only moving the Tigers downtown but to integrate within it. Part of what was already there bore his fingerprints; in 1988 he bought and restored the historical Fox Theater, igniting a chain reaction that brought Detroit’s entertainment district back to life. Ilitch hoped that a new downtown ballpark would breathe further excitement into a city that, not too long before, had teetered on the brink of complete ruin through economic depression, widespread crime and racial strife.

To help get a downtown ballpark its legs, Ilitch gave the team’s CEO role to John McHale Jr., whose father was a Detroit native, Tigers player and later its general manager. McHale Jr. wasn’t brought in so much for family legacy but because, as the legal head of the Denver Metropolitan Stadium District, he had negotiated the deal that would give rise to Coors Field for the Colorado Rockies. His experience in seeing that ballpark through to reality would serve Ilitch and the Tigers well.

For the Tigers to realize their dream of the new ballpark, it would need public financing. And that would mean somehow overturning the voter-approved decree barring such funds for a new sports facility. No problem, said the Detroit City Council—which simply voided the decree on its own. Predictably, lawsuits followed and the public was once again asked to decide. Lo and behold, 80% of the electorate said sure, we’ll change our minds. Why the switch? Maybe it was because proponents spent $60 for every one raise by opponents—or it could have been that Detroiters saw how baseball was revitalizing cities with new downtown ballparks in Baltimore, Cleveland and Denver. Still, there was a last-gasp, post-vote legal challenge by the Tiger Stadium Fan Club—the preservationist grass roots group that admirably fought hard to keep the old yard up and running—but it failed as sentiment for a new ballpark had grown to the point that it now outweighed any concept of a refurbished Tiger Stadium.

Tigers roam everywhere around Comerica Park’s marquee entry, located on the west side off Witherell Street. (iStock)

Dusting Off the Rust.

At first Ilitch proposed an ambitious project called Foxtown, echoing the name of the downtown district where a new ballpark and Fox Theater would initially serve as co-anchors—but the estimated $400 million tab, $230 million of which would have come from public sources, became too much for the city to stomach. Toward the end of 1995, Ilitch went back to the drawing board and came up with a reduced solution, minus the initial extravagance and one block further away from Woodward Avenue, the city’s main drag.

In November 1996, eight months after giving a nod to public financing, voters returned to the booth and approved $85 million of Wayne County money to go toward the new ballpark, to be funded with a combination of local Indian casino revenue and added surcharges on rental cars and hotels. Overruns and inflation would ultimately run the public contribution up to $115 million, but the percentage remained the same as Ilitch and the Tigers put in the rest of the dough, nearly $185 million worth, to help finish the project.

The only drama during construction of Comerica Park was whether Ilitch would be able to pay for his portion of the budget; there was only so many pizzas he could sell. After some searching and sweating, the Tigers finally and publicly revealed that they had a loan in place, nearly two years after voters had given the okay—and almost a full year after ground had broke on the ballpark.

Tigers management had specific ideas of how Comerica Park should look and what it should include, but being that it harbored about as much architectural acumen as Art Vandelay, it wisely brought in Kansas City’s HOK Sport (now Populous), the go-to architects for most of baseball’s new ballparks, to help polish down the look and feel.

Structurally, Comerica Park was the case of fitting a pizza slice-shaped peg into a square hole. It certainly had the space to make it work, filling in six square city blocks of rusted buildings and abandoned concrete. The ballpark bowl would be wedged in and fortified by a series of outbuildings made up a mix of red brick, beige concrete and exposed dark green steel that abutted to the street grid. These outbuildings would be interrupted by the bowl, touching Montcalm Street behind home plate and Adams Street behind the outfield bleachers. It’s the latter area that opened up the ballpark to a Detroit skyline drenched in hues of rust, nostalgia and modern redevelopment.

“It feels like you can reach out and touch the city,” said lead HOK architect Joe Spear to Sports Illustrated. “Obviously we were trying to maintain that view. What we want as ballpark designers is everywhere you look, there is something different to see. That was the idea at Comerica Park.” Spear’s view of Detroit wouldn’t be as breathtaking as what fans in Pittsburgh would see of their downtown from PNC Park, but it subscribed to the openness preached by Ilitch and the Tigers: Here it is, everybody. Embrace it.

Another appealing aspect of the view was that if people could look out of the ballpark, they can look in as well. The Tigers allowed for knothole fan participation as they set up wrought iron fencing along Adams Street to give pedestrians a chance to stop and look in on the action—even if the view was partially obstructed. Getting the optimal view from the outside requires a little stamina; you hop atop a 2.5-foot brick base and then—if you wish—step upon a steel crossbeam another two or so feet above that. From there, you hold onto the vertical rails and hope you can see above the bleacher concourse traffic long enough before muscle fatigue sets in on your arms and wrists. The final caveat: Hope that police walking the Adams Street beat don’t consider your stunt to be a hazard and leave you be.

The outbuildings that surround the Comerica Park bowl house a little bit of everything. In the northeast (third-base) corner of the ballpark, The Beer Hall is an Oktoberfest-style joint with long wooden tables, a 70-foor bar and employees who wear lederhosen. Pacing counter-clockwise to the northwest corner, you’ll find The D Shop, the official Tigers team store. Toward the southwest corner you’ll find The Corner Tap Room, a bar/bistro with a cool neon representation of the old Tiger Stadium signage atop the bar. A little further down, you’ll find The Tiger Club, a members-only establishment featuring a stately exterior façade adorned on each side of the main doors with vertical strips of glazed pottery tiles emblazoned with the Tigers’ old English “D” emblem; inside, fans can dine buffet-style with unobstructed views of the game from the right-field corner.

The ivy-covered batter’s eye behind center field is topped by a dazzling display of light and water known as the Liquid Fireworks. When the Tigers hit a home run, you’ll see it go into action. (Flickr—Girl.in.the.D.)

Carouselambra.

With lots of room to kill between the northern outbuildings and the ballpark bowl, Ilitch—who had something of a thing for amusement parks—decided to give Comerica Park a taste of Carouselambra, as Led Zeppelin once sang. Cropped from the back end of the outbuilding behind the first-base side stands would be the circular Big Cat Food Court, anchored in the middle by the Comerica Carousel—a classic carnival ride featuring tigers for kids to ride on. Designed and built by Wichita-based Chance Rides—the HOK of carousels—this gaudy attraction would be surrounded by a series of food stands serving just about everything, with the more unique menu fare consisting of fried elephant ears, baked potatoes, gyros, hoagies and catfish sandwiches. More traditionally, there would be hotdogs, popcorn and, yes, Little Caesars pizza.

Over behind the third base side, a long horizontal slat of space would be transformed into the Brushfire Grill, an outdoor picnic area with abundant food choices, mostly ballpark favorites with the slant on barbecue. Magnetizing kids and their parents to the back end of this area is the 50-foot tall Fly Ball Ferris Wheel, featuring 12 cabs shaped and designed like baseballs. Proving again that no expense would be spared, the Tigers went to Altavilla Vicentina, Italy to hire Zamperla Inc. to design the 2.5-minute ride.

The collection of amusement park rides within Comerica Park instinctively led to criticism from folks ranging from baseball purists to locals who wondered why their hard-earned tax money was being spent to build this. Even Mike Ilitch, in retrospect years later, would suggest, “I got a little carried away.” But his daughter Denise, part of the family clan active in running the Tigers and helping to get Comerica Park built, saw no shame in the side attractions, telling the Detroit News before the ballpark’s opening, “We don’t want to take ourselves too seriously.” Most fans would come to accept the rides; even the no-frills purists conceded, noting that the attractions were not the distractions as feared because they were separated from the game at hand, behind the main stands.

The final wow factor within Comerica Park’s gates would be the Liquid Fireworks display, placed atop the batter’s eye behind the center field wall. This was, once again, Mike Ilitch’s idea, after being influenced by something he saw elsewhere—perhaps the Bellagio in Las Vegas, or maybe the longstanding outfield fountains at Kansas City’s Kaufmann Stadium. The Liquid Fireworks go into action when water is shot up to 150 feet into the air through 900 stainless steel nozzles, synching to music and lights for a Tigers home run and other positive in-game moments. Even Joe Spear was impressed at Ilitch’s foresight on the water display. “It was an opportunity to create some dynamic views out of what might have been a pretty ordinary batter’s eye,” he told SI. “I thought it was a great idea.”

Because everything has to be sponsored at the ballpark in the name of revenue optimization, the Liquid Fireworks are brought to you by GM—and that’s probably because it badly wanted exposure given that local automotive rival Ford had its name prominently slapped upon the façade of adjacent Ford Field, the new home of football’s Lions built shortly after Comerica Park’s completion. GM hasn’t always had its name—along with a couple of its new cars—on the fountains; pummeled by the Great Recession in 2009, it balked at sponsorship for a year as it didn’t have the money to justify the expense.

Hard Opening, Hard Lessons.

The opening of Comerica Park on April 11, 2000 came with all the pomp and pageantry one would expect with the debut of a new ballpark. It also came with atrocious weather, as conditions were more befitting of a football game at Green Bay’s Lambeau Field. First pitch temperatures hovered in the upper 30s with a wind chill just above 20; a dreary, gray sky only made it feel colder. Groundskeepers hosed down the Kentucky bluegrass field to melt away a light glaze of snow that had stuck around.

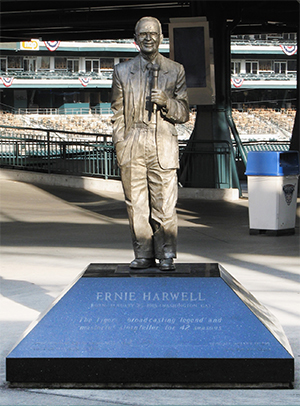

Behind the first base-side seats stands a bronze treatment of legendary Tigers announcer Ernie Harwell. When he passed away in 2010, his body lay in repose at the ballpark for fans to pay their final respects. (Flickr—Race Bannon)

As special as Comerica Park’s debut was, the Tigers quickly realized they had made the mistake of not holding a ‘soft opening’ exhibition like so many other new ballparks before and since. The lack of any rehearsal led park employees to experience a baptism by fire on an icy day, and the fans who paid top dollar to watch real baseball—not preseason fare—became the guinea pigs. Concession lines became insufferably long. Beer ran out. Ketchup ran out—and so soon did the hotdogs to put it on. ATMs crashed. Ushers were few and far between to assist fans; it was speculated that they were intentionally making themselves scarce to protest a no-tip policy established by the Tigers. A fire alarm sounded an hour before the first pitch; the joke was that a Tiger Stadium preservationist had pulled it. Vendors even ran out of programs. One fan summed it all up to a Detroit Free Press reporter: “I tried to buy food and I couldn’t; I tried to buy a program and I couldn’t. I even tried to pay someone to buy a program, but he wouldn’t. I’ve got lots of money and nothing to spend it on.” It was an embarrassing set of circumstances for the Tigers, who had bragged that there would be a “point of sale” for every 125 fans—almost half the major league average.

When the fans weren’t stuck in line, some were chaffing at Comerica Park’s seating arrangements—which presented something of a cultural shock to Tigers fans ingrained with 90 years of Tiger Stadium’s compact, enclosed frame. The biggest beef came from fans in the lower level who complained that the gradual pitch of the rows made it difficult to see above the person seated in front of them. Overall, Comerica Park’s two decks of seating—with two levels of suites in between, running from first base all the way to the left-field corner—seem laid back and hardly on top of the action, a far cry from those right-field bleacher seats in Tiger Stadium’s upper deck that actually hung out over the warning track.

Something that caught the eye of most people as they checked out the ballpark for the first time was the unique seats found at the back of the field level. From pole to pole, fans here feel like they’re watching the game from their backyard—and that’s because they spaciously sit in patio-style chairs with cushioned seats and an accompanying side table, like something out of a L.L. Bean catalog. This is the Tiger Den, the seats from which are among the most expensive in the house—but also those that come with a private ballpark entrance, in-seat concession service and exclusive use of the Den Lounge, which includes a full bar and dining.

With the possible exception of the suites, the most relaxed seats at Comerica Park can be found at the back end of the field level, where fans sit in a comfortable environment more befitting of a backyard patio. (Copyrighted Photograph by Tupac Apmadoc, Used by Permission)

Comerica National Park.

As Comerica Park’s inaugural season wore on, the lines began to shrink as the flow of concessions improved, and lower-level fans learned to live with the challenged sightlines. But the players—especially those who were paid to hit—constantly complained about an altogether different problem: An overly spacious playing field.

Throughout the 1990s, Tiger Stadium had evolved into one of the majors’ more notorious bandboxes. The emerging steroid era may have had something to do with it, but so did the Tigers’ penchant for bringing in muscle-bound sluggers. While it helped the team look impressive in the power section of stat sheet, the final standings were often a different story; during Tiger Stadium’s final decade, the Tigers led the American League in home runs—and losses. Detroit pitching was especially hard hit; in 1996, the Tigers’ staff posted a 6.38 earned run average, the worst in AL history.

Comerica Park’s playing field borrowed from its predecessor in that it would be mostly square-shaped (except for a triangular slice shaved from center field, lest it infringed upon Adams Street) and that the park’s flagpole would be planted in play on the warning track in center. But it would be a much bigger expanse—in part, because team CEO John McHale Jr. had grown tired of the cheap home runs being slapped out at Tiger Stadium. “Of the balls that just crept over the 365 mark or the 325 mark (in Tiger Stadium’s right field corner) during the last five years, many of them appeared not to be well hit,” McHale Jr. told the Detroit Free Press. “It’s arguable whether in the modern era those should be considered home runs and have such an impact on the game.”

So McHale Jr. decided to forge Comerica Park’s field dimensions so that the cheap homer would no longer be possible. But with the outfield wall being set at 420 feet to straightaway center and a few feet under 400 just to the left-field power alley, some wondered if any home run would be possible.

No one cleared the fences in Comerica Park’s first game. Nor did anyone do it in the second game, or the third game. In their first homestand at the new ballpark, the Tigers were shut out four times in eight games. Right-handed hitters may have felt particularly screwed by the enormous real estate in left field, but left-handers attempting to reach the relatively shorter fences in right field had to contend with prevailing winds that typically blew in toward them.

Ultimately, the Tigers hit 69 longballs at Comerica Park in 2000—49 fewer than what they had belted in their final year at Tiger Stadium. Everyone on the team complained. Even the pitchers complained, stating that their hitters weren’t getting a fair chance at the plate. Outfielder Bobby Higginson, who would lead the Tigers with 30 homers (18 of which were hit on the road), lambasted the new ballpark by referring to it as “Comerica National Park.”

Juan Gonzalez was more direct in his criticism. He called Comerica a “horses**t ballpark.”

In the previous four years, Gonzalez had been a terror upon AL pitchers, winning two MVPs and averaging 50 homers and 160 runs batted in per 162 games played for the Texas Rangers, who held court in an offensively attractive ballpark. After the 1999 season, Gonzalez was the prime component of a nine-player trade that made him a Detroit Tiger. But Comerica Park ate him up and deadened his numbers, as he hit 22 homers (just eight at home) with 67 RBIs in 2000; in previous years, that’s more likely what he would have accumulated before the All-Star break. Gonzalez so hated the Comerica experience, he spurned a lucrative eight-year, $140 million offer to stay in Detroit after 2000 and signed instead for one year and a relatively paltry $10 million with Cleveland—where he resumed his pre-Comerica annihilation, hitting .325 with 35 homers and 140 RBIs for the Indians.

The lack of power produced at Comerica Park gave the impression that the new facility was a pitcher’s paradise, but that wasn’t exactly true. What Comerica took away in home runs it gave back with an increased number of singles, doubles and triples, as the expansive outfield provided more room for hitters to deposit base hits in between outfielders. The result was a healthy .282 batting average yielded in Comerica’s first year—still the highest recorded number, though it’s a figure that’s been continuously challenged as averages in the .270s are common. Comerica Park also became a perennial league leader in triples, with 74 alone collected in 2001—the highest total at a Detroit ballpark since 1930. Had Ty Cobb in his prime been transported to Comerica via time machine, he would have loved the place.

There were a few more kinks to work out as Comerica Park ran its course through its first year of operation—some of which the Tigers simply couldn’t do anything about. The setting sun, behind the first-base stands, bounced off of downtown buildings and produced an intense glare into the eyes of fans seated in the upper level. And among those checking out the ballpark in its first year was a swarm of flying ants—yes, flying ants—that infiltrated the venue one August evening, sending much of the crowd of 32,000 fleeing from their seats and demanding refunds. But the game went on, and no one was happier than the local birds who feasted upon the insects.

After right-handed sluggers complained that Comerica Park was too tough a place to hit a home run, the Tigers moved the left-field wall from the front of the bleachers 30 feet into the outfield. The vacant space created room for bullpens moved over from behind right field. (Flickr—Ken Lund)

The Great Regression.

It’s typically touted that a team needs a new ballpark to stay competitive. This seemed especially true for the Tigers, who in their last six seasons at Tiger Stadium posted six losing records.

But in their first six years at Comerica Park, they posted six more losing records. So much for keeping up with the Joneses.

The Tigers nearly scraped the .500 mark in their first year at Comerica Park, finishing the 2000 campaign with a 79-83 record. But that proved to be a high-water mark of sorts. Over the next three seasons, the Tigers didn’t merely go downhill; they went off a cliff. They lost 96 games in 2001, followed by 106 in 2002, followed by a horrific 43-119 showing in 2003; had they not won five of their last six games that year, they would have made the infamous 1962 New York Mets look rather respectable by comparison.

As the losses piled up, so did the unused tickets at Comerica Park. The Tigers drew 2.5 million in their first year at the new yard—at the time, the second highest total in franchise history, but still short of the three million the Tigers had hoped for—and by time the turgid 2003 season rolled through, attendance had dropped all the way down to 1.368 million. And mind you, that’s tickets sold, not the actual people who bought them and bothered to show up. Things got so bad, the Tigers reportedly had to take out a loan just to make payroll.

There was also unwanted public relations drama surrounding the saga of Comerica hotdog vendor Charley Marcuse, who was known throughout the park for offering his product using a loud, operatic voice that charmed some fans and annoyed others, including team broadcasters who tired of picking up his voice on the field mic. Marcuse might have won over more spectators had he not chastised them for asking for ketchup, but the Tigers fired him anyway. After a fan revolt, the Tigers brought him back to Comerica Park, where he continued to work until 2013—when he was fired again, this time with much less fanfare.

As the new ballpark smell was overwhelmed by the stench of a rotting Tigers roster, the players’ major beef was addressed. With nothing much left to lose in 2003, the team decided to move in the left-field fence nearly 30 feet. While the ballpark’s other dimensions stayed the same—most importantly, the 420 to dead center—the reduced space to left was enough to put smiles on sluggers; for the next two years, it was estimated that 100 home runs wouldn’t have cleared the wall in the old configuration. Not surprisingly, the frequency of doubles and triples trended downward—but at least the possibility of running into the flagpole was eliminated as the Tigers moved it behind the wall. By 2005, the vacant area created between the moved-in fence and the bleachers in left would be filled up with new bullpens; the old pens, tucked behind the right-field wall near the foul pole, were cleared for nearly 1,000 additional bleacher seats.

Better Times.

Beyond the wall re-adjustment, the only other issue in need of a major fix during Comerica Park’s early years was the team itself. That was finally take care of when, in 2006, the Tigers under the guidance of veteran manager Jim Leyland took the team to its first AL pennant since the “Bless You Boys” juggernaut of 1984. The campaign produced the ballpark’s most memorable moment to date when Magglio Ordonez broke a 3-3 tie in Game Four of the AL Championship Series with a three-run home run—his second blast of the game—to give Detroit the flag over the Oakland A’s. And just in case you were wondering: Both of Ordonez’s home runs would have been deep enough to clear the original, more distant outfield wall in left.

The Tigers went on to lose to the St. Louis Cardinals in the World Series, but the euphoria of a surprise pennant reignited major interest from the locals. Though they didn’t return to the postseason until 2011, the Tigers remained competitive and exciting enough a team that fans clicked through the Comerica Park turnstiles at season totals often exceeding the magical three million mark. Leading the way on the field were two Cooperstown-bound stars who remain, far and away, the leaders in most statistical categories among games played at Comerica: Miguel Cabrera and Justin Verlander.

Traded to the Tigers from the Florida Marlins in 2008, Cabrera has staked his claim as one of the game’s great hitters of this or any era. With the Tigers, he has won four batting crowns, two MVPs and, in 2012, baseball’s first triple crown performance in 45 years when he led the league with a .330 average, 44 home runs and 139 RBIs—the latter two numbers representing career highs. Comerica has been no problem for Cabrera—honestly speaking, no ballpark has—as he’s hit some 15 points above his career average at the venue.

On the mound, Verlander’s rise in Detroit paralleled that of the Tigers in 2006. The 6’5” fastballer, who’s shown the capability to throw 100 MPH well into his career, is closing in on 100 lifetime victories at Comerica while no one else has surpassed 50. His season of seasons came in 2011 when he won both the AL Cy Young and MVP awards with a terrific 24-5 mark and 2.40 ERA. Better known to those among the TMZ crowd as the beau of supermodel Kate Upton, Verlander is responsible for the only no-hitter in Comerica Park history, when he shut down the Milwaukee Brewers on June 12, 2007.

There might have been—scratch that, should have been—another no-hitter at Comerica had it not been for a massive umpiring gaffe during a June 2010 game between the Tigers and Indians. Detroit right-hander Armando Galarraga, badly struggling for consistency after a fine 2008 rookie showing, was sailing through the afternoon as he retired the first 26 batters. Just one out away from the first perfect game in the 110-year history of the Tigers, Galarraga induced a ground ball from Jason Donald to the right side of the infield that was gloved away from the first-base bag by Cabrera—who threw to Galarraga, racing over to cover at first. Galarraga clearly beat Donald to the bag by half a step, but umpire Jim Joyce inexplicably ruled him safe. The blown call made national headlines and helped hasten the advent of comprehensive video replay later in the decade.

Mo Town?

Comerica Park was built in part to jumpstart downtown Detroit, to make it chic and safe for suburbanites to feel comfortable returning to. Of course, the ballpark is hardly the only piece of the redevelopment puzzle; there has also been Ford Field (home of the NFL’s Lions), Foxtown with all of its entertainment entities, three major casinos, an infusion of corporate headquarters (GM, Compuware and Quicken Loans) and the rehabbing of old buildings into upscale residences. All this, and the progression of downtown Detroit from ghost town to The Place to Be continues to be a slow one—and not so much a sure one. Many downtown buildings remained empty. Half a mile west of Comerica Park, whole square blocks remain empty of anything—it’s just a desert of concrete, with an occasional structure sticking out like a lonely oak amid a vastness of prairie. The downtown People Mover, an elevated light rail loop with a stop two blocks from Comerica Park, rarely gets any people on board to move. Local government has been no help; compressed under the weight of widespread corruption, the City of Detroit declared bankruptcy in 2013.

Busts of tigers heads lend a fiercely ornate decoration to the ballpark’s exterior; the baseballs gripped within their jaws light up at night. (iStock)

For now, fans who want to peruse around Comerica Park before or after the game do have some enduring spots to rely on. Two blocks to the west, next to the Fox Theatre, there’s the famed Hockeytown Café, said to be the premier off-Comerica go-to for Tigers fans. It’s a dazzling and colorful grub joint so adorned with motorcycles, you’d wonder if you’re entering a restaurant or a Harley museum. Part of Hockeytown is actually a theater, with 430 seats for concerts, plays and stand-up comedy; it once ran a play called Ernie, about legendary Tigers announcer Ernie Harwell. Then there’s the Elwood Bar & Grill (since 1936), which had to be relocated to make way for Comerica Park—but no one’s complaining, since it’s current location is a prime locale that not only sits on the corner across the street from the southeast entrance to Comerica, but also across the street from the front doors of Ford Field.

Tiger Tide of Progress

Comerica Park has not stood pat through its relatively young life. The ballpark adjusted to the hi-def world by updating its main scoreboard behind left field in 2012—and also made a type adjustment by changing the old-style, serif “Tigers” font that had arced across the top of the board into a cursive treatment derived from the “Detroit” script that often graces the Tigers’ road uniforms. Two years later, the Tigers bowed to the younger crowd by amending the Pepsi Porch plaza behind the right-field bleachers and establishing the New Amsterdam 416 bar—the “New Amsterdam” being the vodka maker that sponsors it, the “416” indicating the distance from home plate to the front of the bar. It’s an expansive lounge which includes balcony-style seating, patio-style sofas, TVs everywhere in case you miss something on the field and, but of course, an open, covered bar serving as the beacon for all ticket holders to come and enjoy. Behind the plaza and atop the indoor Jungle bar are 300 new seats for those who’d rather pay less and use binoculars; these bleacher-style seats are roughly 550 feet away from home plate.

Mike Ilitch, the Lord of the Tigers and the man who, more than any other, has helped reshape downtown Detroit for the better, died in the Winter of 2017. His legacy remains a fluid one as development started under his wing continues on, but with him the city and the Tigers have both come a long way from Tiger Stadium’s fruitless stabs at rejuvenation. Older fans might still pine for the days of lore at The Corner where baseball ruled for over a century, but they also understand that progress is progress, and have come to embrace Comerica Park, with its brash mix of history, carnival rides and tiger sculptures. The younger fans, some of who probably never bore witness to a game at Tiger Stadium, likely don’t have their hearts as torn between old and new. To them, Comerica Park is it—good, bad or garish.

And so the fans have settled in, and they seem content. And perhaps that’s just the way Mr. I would have liked it.

The Ballparks: Tiger Stadium For a city that prides itself on automotive excellence, Detroit managed to get a century’s worth of mileage out of Tiger Stadium, a deceptively intimate ballpark that was periodically tuned up and souped up within its white walls. The Tigers may have moved on, but “The Corner” perseveres as a vivid, lasting memory—just as it did through boom, bust, urban decay and the many attempts to tear it down.

The Ballparks: Tiger Stadium For a city that prides itself on automotive excellence, Detroit managed to get a century’s worth of mileage out of Tiger Stadium, a deceptively intimate ballpark that was periodically tuned up and souped up within its white walls. The Tigers may have moved on, but “The Corner” perseveres as a vivid, lasting memory—just as it did through boom, bust, urban decay and the many attempts to tear it down.

Detroit Tigers Team History A decade-by-decade history of the Tigers, the ballparks they’ve played in, and the four people who are on the franchise’s Mount Rushmore.