The Ballparks

Comiskey Park

Chicago, Illinois

When you get your ace pitcher to design your ballpark, you’re going to get a pitcher’s park. And that’s what Comiskey Park was, extending the Deadball Era for decades as the Second City’s Second Team experienced little offense but an explosion of scandal, scoreboards and disco records for a lively and sometimes unruly South Side fan base.

Winning isn’t everything, someone once wrote. At Comiskey Park, it was far from being the only thing. Most memories from what was initially nicknamed the Baseball Palace of the World seemed to consist of as much infamy as fame, and of indelible moments that had nothing to do with the White Sox winning ballgames.

Unpredictability ruled. The 1919 White Sox failed to win the World Series because eight members of the team were quietly paid to lose. The 1967 White Sox nearly won a pennant despite hitting just .208 at Comiskey Park. And the 1990 White Sox hit even worse—as in .000—in one game during the ballpark’s final season and somehow still managed to win, 4-0, proving they were Hitless Wonders to the end.

The White Sox did perform well at Comiskey—winning over 400 games more than they lost—but championships were hard to come by. In eight decades of play at the ballpark, the White Sox only won three pennants and just one world title, in 1917. But there was seldom a dull moment, good or bad. Three All-Star Games, including the very first in 1933, were played at Comiskey. So were numerous Negro League All-Star affairs—27 in all. Sonny Liston KO’d Floyd Patterson in a 1962 boxing bout that was one of the few sanctioned fights that didn’t take place in the bleachers. The Chicago Cardinals won a National Football League championship at Comiskey in 1947; over 70 years and two relocations later, they have yet to win another. And in its early years, Comiskey Park even hosted auto polo. Yes, auto polo—think cars instead of the horses. One can only imagine the heartache the groundskeepers had to endure getting the field back into baseball shape.

Though seating nearly 50,000, the double-decked Comiskey was an intimate paradise, with great sightlines and only a dozen or so rows in its upper deck. But “cozy” was not a word frustrated sluggers often used to describe the ballpark, with its voluminous, symmetrical outfield spaces keeping deep flies from clearing the fence; prevailing winds shooting in from Lake Michigan didn’t help. No one player ever hit more than 100 homers at Comiskey, a remarkable fact given its longevity. But that’s because the White Sox were smart enough to build their rosters on tenacity, speed and line drives—not muscle-bound boomers who would have found themselves snapping bats into two after the latest 400-foot out.

Comiskey Park was a Deadball Era park that remained one well after the live ball began to take hold. And for the authors of the ballpark, that would be music as sweet as smooth jazz on the South Side.

Zach and Ed Make a Ballpark.

One of the American League’s eight original franchises, the White Sox began play in 1901 at South Side Park, the third such Chicago ballpark to go by that name. AL founder Ban Johnson and Charles Comiskey, his good friend, right-hand man and owner of the league’s Chicago entry, secured a loan to build the wooden structure with their “good names” as collateral. This leap of faith proved worthy as the White Sox established a loyal following, matched their northern rival Cubs ticket for ticket and took their first World Series title in 1906, defeating the then-almighty Cubs. But Comiskey had maxed out capacity of South Side Park at 15,000 and had no room to expand; a partial burn of the grandstand in 1909 further convinced him that a new ballyard, made of steel and concrete, would be a good idea.

By then, Comiskey had already begun to make his move. He paid $150,000 for 15 acres of land owned by former Chicago mayor John Wentworth, a few blocks to the north of South Side Park. Part of the land was being used by a farmer who grew fresh produce that Comiskey himself sometimes bought; it was also said to be a trash dump, though some have disputed that notion. Don’t tell that to White Sox Hall-of-Fame shortstop Luke Appling, who during a game in the 1930s once found himself stepping on something hard in the infield; a little digging turned up a tea kettle, apparently buried for years.

To design the new ballpark, Comiskey put together a team led by two very disparate individuals. One was Chicago architect Zachary Taylor Davis, who once apprenticed alongside the legendary Frank Lloyd Wright and, at age 40, was settling into his prime. Already locally accomplished in conceiving churches, schools, and courthouses, Davis would add ballparks to his portfolio with Comiskey Park; he would later design Wrigley Field, lend a hand in idealizing Yankee Stadium, and even draw up the look and feel for the other Wrigley Field in Los Angeles, briefly used by the Angels before their move to Anaheim. Cubs owner William Wrigley was so pleased with Davis’ work that he commissioned him to design one of his homes away from home, on California’s Santa Catalina Island overlooking the charming coastside town of Avalon. (It’s now a bed-and-breakfast.)

The other half of the Comiskey design team was Ed Walsh, the team’s workhorse ace who personified the zenith of Deadball Era ethic in 1908 when he threw 464 innings and won 40 games. Walsh wasn’t interested in Davis’ architectural ideas, so long as they didn’t inhibit his plans to keep the playing field as large as he could make it.

Together, Davis and Walsh traveled to the few new steel-and-concrete ballparks already constructed for ideas. They both liked Pittsburgh’s Forbes Field the most, for different reasons; Davis, for its elegant appeal and use of arches; Walsh, for its expansive outfield that instantly negated any hitter’s ambition to drive one over the wall.

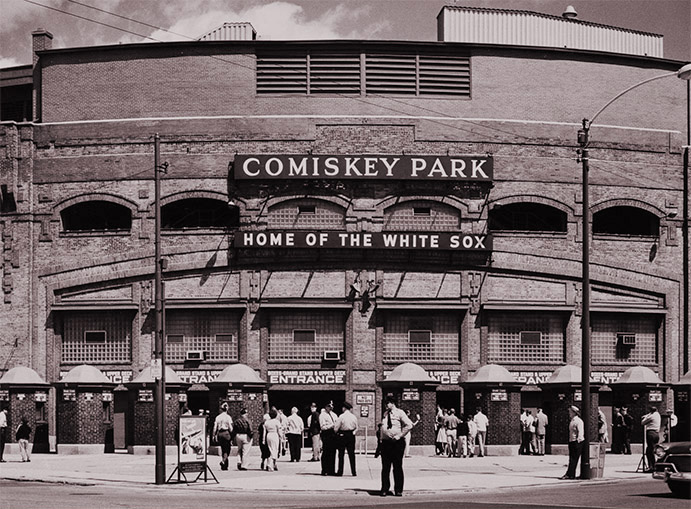

Davis’ exterior vision was one that blended many styles. His ode to Forbes Field was also an indirect one to the Roman Coliseum with its repeating arches; the widespread entry, complete with a complex but orderly collection of extruding blocks of arts and crafts motifs and an elongated entry arch nameplate, echoed the “Prairie School” design that he, Wright and other midwestern architects of the day embraced; and the exterior was cast in red brick to blend in with surrounding factories. A dozen ticket queues guarded the entry in semi-circular fashion.

Some of Davis’ more ambitious plans were vetoed by Charles Comiskey, who had a reputation for playing it cheap—just ask the Black Sox Eight of 1919. A more ornate façade was pared down, a proposed third deck was deleted, and external landscaping including a fountain behind the first-base portion of the structure never made it past the drawing stage. Davis also envisioned cantilevering the second deck, but that was nixed—leading to the reality of some lower bowl fans having to sit behind supporting posts.

Once the blueprints were approved, construction on Comiskey Park was fast and furious. It took less than five months and $600,000 to complete—a timespan that included a loss of five weeks’ worth of activity when steelworkers went on strike. A month into construction, the White Sox laid down the ballpark’s cornerstone in a ceremony that included Comiskey, Davis and catcher Billy Sullivan—a charter member of the White Sox about to play his 10th season for the team, returning from Ireland with a block of “auld sod” to place down.

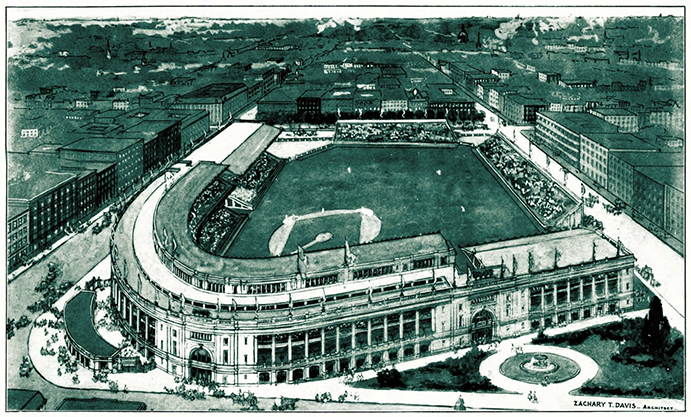

Architect Zachary Taylor Davis’ early renderings of Comiskey Park called for a more extravagant façade and a formal fountain (lower right). White Sox owner Charles Comiskey, never one to spend freely, curtailed some of Davis’ visions.

Hitless Blunders.

It was a special occasion indeed when White Sox Park, as Comiskey was known through its first three years, opened on July 1, 1910. Among the overflow crowd of 30,000 was both league presidents and numerous other team owners to pat Charles Comiskey on the back for a job well done. Not showing up, as usual, was the White Sox’ offense. Ed Walsh’s wish for a pitcher-friendly park became too much of a good thing as he lost a pitcher’s duel to Barney Pelty and the visiting St. Louis Browns, 2-0. While Chicago bats stayed cold, the field was on fire—literally. According to the Chicago Examiner, the grass suddenly erupted in flames near the Browns’ dugout; nearby players beat the fire down with bats. No explanation was given; maybe the alleged dump underneath provided an unwelcomed bit of spontaneous combustion.

Low scoring and poor hitting—at least on paper—would be the rule at Comiskey Park during its first decade, as the offense struggled to put up big numbers on a field that measured 363 feet down the lines and 420 to center. The ballpark’s inaugural half-season in 1910 would be especially brutal; the White Sox and their opponents combined to hit just .203 in 51 games. Only three home runs were hit—all of them of the ground-rule variety as they bounced through iron gates positioned near each foul pole that connected the bleachers with the single-decked grandstands down the lines. The year’s highlight, from a purely pitching perspective, was a scoreless, 16-inning duel between Walsh and the Philadelphia Athletics’ Jack Coombs, the latter of whom struck out 18 batters—a ballpark record that would only be matched in 1976 by Nolan Ryan in a nine-inning contest. Of the 105 total homers hit throughout Comiskey’s first decade—and the last of the deadball’s rule—62 were inside the park.

The biggest hit recorded early on at Comiskey Park was the ballpark itself. Fans flocked to a facility anchored by covered, double-decked grandstands that stretched from first to third, covered single-decked stands down the lines and bleachers separated by a gigantic white wall behind center field partially covered by ads and scoreboards. Four times in their first full seven seasons at Comiskey, the White Sox led the American League in attendance; that they played winning baseball didn’t hurt. In fact, the park was home to the World Series each year from 1917-19—with the White Sox participating in two of them. In 1918, the Cubs decided to use Comiskey in their six-game loss to the Boston Red Sox because it held 10,000 more seats than recently-built Wrigley Field. The Cubs didn’t sell out any of the three games at Comiskey; maybe North Side fans couldn’t bear to go to a “home” game on the rivalrous South Side.

The neighborhood around Comiskey came alive with the new ballpark. Real estate prices rose dramatically during the first five years, and a South Side institution was established with the opening of McCuddy’s Tavern, initially built to service those building Comiskey. Once the workers left and the fans came, the tavern became the meeting place for generations of White Sox loyalists; even the players stopped by on occasion. Not surprisingly, Babe Ruth was a frequent visitor after yet again making Comiskey look positively small—he hit 45 career homers in 179 games at the ballpark, including the first ever hit over the tall center-field wall, in 1922. A bat with Ruth’s signature remained on display at McCuddy’s until the joint was forcibly torn down in 1988 to make away for part of the lower third base-side concourse at what’s now Guaranteed Rate Field.

For those with social connections to Charles Comiskey, there was a more alluring alternative to McCuddy’s. The Bard’s Room was an exclusive club located under the grandstand where men of note could gather, converse, light a stogie and imbibe. It had the feel of a rustic yet upscale upper Midwest cabin—paneled in mahogany, decorated with deer heads and made warm with a brick fireplace. The White Sox opened the room up to the press on occasion, and the writers soon took it over when Comiskey and his pals passed on or faded away. When maverick owner Bill Veeck bought the team in 1959, he couldn’t resist the temptation to make the Bard’s room his personal office, so he did.

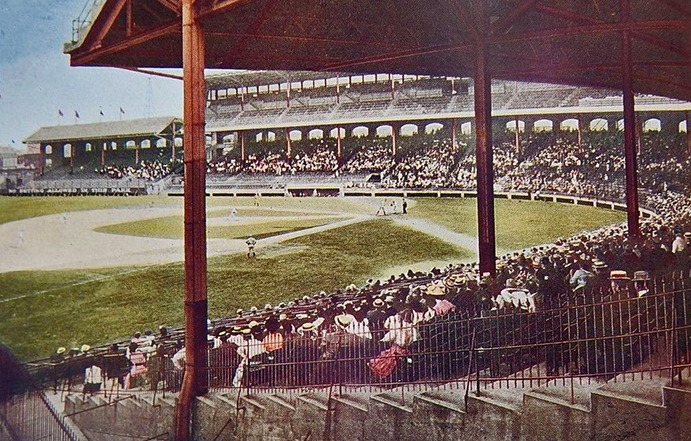

This colorized postcard from 1911 shows Comiskey Park’s original structure, consisting of a double-decked grandstand curling around the infield abutted by single-decked pavilions down each line.

Reach for the Roof.

Few adjustments were made to Comiskey Park in its early years. The backstop, which at first was a distant 98 feet from home plate, was moved to within 82 feet with the installation of additional box seats. The bleachers were also expanded. But with the baseball boom of the 1920s as scoring, home runs and attendance soared, Comiskey Park became part of the movement of steel-and-concrete ballparks going through major expansion. For the White Sox, adding seats to Comiskey had nothing to do with the team’s performance—they were suffering through an extended hangover in the wake of the catastrophic Black Sox Scandal—and it wasn’t so much about adding seats for the 11 annual appearances of Ruth, Lou Gehrig and the rest of the powerful Yankees. It was, in fact, a reaction to the booming (if in part illicit) Chicago economy that made kings of men like bootlegging gangster Al Capone.

Architecturally overseen once more by Zachary Taylor Davis, the expansion of Comiskey Park nearly doubled capacity to 52,000; 2,000 additional seats didn’t make the final cut, a victim of building code regulations. The double-decked grandstand was extended almost completely around the field, leaving only an uncovered notch of single-leveled bleachers behind center field. To complete the expansion behind right field, additional land had to be purchased. Seats and aisles would be widened, and hand-operated scoreboards were inserted into the outfield walls in both left and right field, which were now 10 feet tall; at center field, it was said to be 15 feet—but photos of the time seem to suggest something closer to 20. Additionally, the flag pole in straight-away center appeared to be in play, right in front of the wall.

The double-decking of the bleachers, which unfortunately cut off the view of downtown Chicago, made for a new and sensational target for sluggers who dared to clear the roof above. The Sporting News counted 44 homers that either hit atop the roof or sailed completely over it. Naturally, Babe Ruth was the first to do it. But there is historical confusion on who actually hit the longest homer in Comiskey Park annals. The A’s Jimmie Foxx hit what many considered the longest in 1930 with a blast that soared over the left-field roof, but there’s no measurements to back it up. In 1955, witnesses swear that Mickey Mantle also cleared the left-field roof with a ball that landed through the window of a parked car on 34th Street; that shot was measured, at 550 feet. And in 1964, the White Sox’ Dave Nicholson—who just a year earlier had whiffed 175 times to easily set a major league record (easily since broken)—connected on a drive measuring 573 feet. But there was dispute on whether the ball hit the roof on its way out, and whether the official length included the bouncing of the ball to its final resting spot outside of the ballpark.

The expansion of seating at Comiskey Park was accommodated by an expansion of the field. The 1927 configuration would be as large as it got at the ballpark; although the distance down the line held fairly steady (from 363 feet to 365) and the power alleys slightly shrunk (from 382 to 375), the footage to straightaway center was an exhausting 455 feet—and since the field’s shape was now essentially a square with a clean diagonal bite taken out of the center-field corner, the distance to the areas just left and right of center were even longer, at roughly 460 feet. Live ball be damned, thought Charles Comiskey; go ahead and take your best shot at it, as he teased sluggers who didn’t have the chops of a Ruth, Foxx, Mantle or even Nicholson to reach for the roof.

There were times when the White Sox had a change of heart with the distant walls—usually when they felt it would play to their advantage. In 1933, the team acquired future Hall of Famer Al Simmons, who averaged 32 homers per season in his previous four years with the Philadelphia A’s. But he hit just 14 homers in his first season with Chicago. It wasn’t entirely Comiskey Park’s fault; he hit just as few homers (seven) on the road as he did at home. Simmons blamed the ballpark anyway, warning the White Sox that he wouldn’t report in 1934 unless the team moved the fences in. In response, the Sox actually moved home plate 14 feet closer to the walls. It only helped in that an aging Simmons hit more homers at Comiskey to mask what was diminishing returns on his fading power. Worse, the White Sox never benefitted in the standings from Simmons’ presence, as they finished below .500 in each of his three seasons at Chicago before sending him elsewhere. As soon as he was gone, the White Sox moved the infield back to its pre-Simmons location.

The White Sox toyed most boldly with the field dimensions in 1949 when enterprising first-year general manager Frank Lane ordered ballpark workers to place a canvas-covered fence rising just five feet high in front of the walls, cutting down the dimensions anywhere from 10-to-20 feet. Lane perhaps was hoping to shake up a White Sox team that had lost 101 games the year before, or to give Chicago slugger Pat Seerey—who had homered four times in a game the year before—an extra power boost. But it was quickly apparent that visiting teams were taking more advantage of the reduced spaces, depositing far more homers than the White Sox. When the Washington Senators, not exactly the personification of power, came to Comiskey and hit a ballpark-record seven homers in one game in early May, Lane put the brakes on the whole thing and had them removed—just in time for the mighty, muscular Yankees to show up for the next series. The moved irked AL officials, who later established a rule forbidding midseason movement of outfield fences.

Those who forget the past are condemned to repeat it. Which brings us to the 1969 White Sox, which tried the same thing 20 years after Lane first thought it up. Same idea, same result, as a bad Chicago team was once again badly outhomered—though this time it took two full years for the Sox to admit it before relegating the fences to parking enforcement.

Despite all the fence adjustments, there was one thing that always remained the same at Comiskey Park: Symmetry. There were no odd, uneven angles, unlike so many other ballparks of its era that found themselves conforming to street grids and random bleacher placements. The left side of the field—the height of the outfield walls included—was always a perfect mirror image of the right. Comiskey Park was said to be the first ballpark with purely symmetrical dimensions, and it stayed that way through to its last day standing.

The wide arches and boxy reliefs seen here at Comiskey Park’s main entrance is indicative of the “Prairie School” brand of architecture that was popular in the Midwest during the early 20th Century.

All in the Family Feud.

During Comiskey Park’s first decade, the man from whom it was named after remained one of baseball’s most powerful execs—certainly the second most powerful in the American League behind “czar” Ban Johnson. But the Black Sox Scandal, followed two years later by the death of his wife, broke Comiskey. The White Sox went into a prolonged funk in the wake of the scandal, and after the 1931 season—the 11th straight in which the team finished no higher than fifth in the eight-team AL—Comiskey passed away. His son, Lou Comiskey, took over as White Sox owner and made them more relatively competitive by the end of the 1930s, with one major addition to Comiskey Park: Lights, installed late in 1939. But Lou never got to see the Sox’ first night game; an obese man who binged on chocolates, he died of heart disease just weeks before, at age 52.

Lou bequeathed the White Sox to the First National Bank of Chicago with the idea that they’d pass it on to his wife, Grace—who in turn would pass it on to son Chuck once he turned 35 in 1960. But the bank didn’t think the team was a wise investment and, perhaps more privately, thought Grace lacked the masculinity to properly run it—and decided to sell to outside interests. Grace was not amused, and after a year-long legal battle ultimately got control of the franchise. The second female owner in major league history, Grace oversaw modest upgrades to Comiskey Park, including installation of newer and wider seats, increased concession stands, an improved press box and, importantly for the fans, more toilets. The White Sox were in the early stages of a four-year, $500,000 “improvement plan” to further freshen up Comiskey Park when Grace died in 1956.

Chuck’s hopes of gaining majority ownership of the team four years earlier than anticipated were rudely dashed when Grace’s will revealed that he’d get 46% of the team’s stock—while the rest went to his sister Dorothy, who just happened to be married to former White Sox pitcher Johnny Rigney, who just happened to have a top front office job within the team. This infuriated Chuck, who spent the next two years burning through lawyers and practically living in a courtroom, trying—in vain—to wrestle control away from Dorothy. Likely tired of it all by 1959, Dorothy decided to sell, telling Chuck that if you want my 54%, give me your price. Chuck, believing that he would be the lone bidder, came back with a paltry offer. An insulted Dorothy turned around and sold her majority control to one Bill Veeck.

BOOM!!!

A brief success as owner of one franchise (the Cleveland Indians of the late 1940s) and a brief failure with another (the St. Louis Browns of the early 1950s), Bill Veeck was at least consistent in one aspect: He took adventures in promotion to the edge. Some of his gimmicks were utterly audacious, most infamously recalled when he sent 3’7” Eddie Gaedel up to bat during an actual 1951 game for the Browns because of his miniature disposition. Those who believed that Veeck was going to mellow and lead a relatively vanilla ownership with the White Sox were in for a rude—and loud—surprise.

There were plenty of tricks left in Veeck’s promotional bag. As owner of the White Sox, he once gave away a 299-pound block of ice as a prize to a fan on a hot day—though one wonders, if it didn’t melt by the time the fan got it home, whether there was a freezer big enough to store it. When Veeck couldn’t get President John F. Kennedy to attend the White Sox’ home opener, he grabbed a local phone book, found someone with the same name and invited him to throw out the ceremonial first pitch. Before another game, a helicopter landed in the middle of the field and out ran four pint-sized “Martians” (including Eddie Gaedel) in spacesuits who told players to “take us to your leader.” As for Comiskey Park itself, Veeck gave the park its most jarring makeover yet by repainting the brick red edifice completely white, while placing a “picnic” area underneath the left-field bleachers that would allow fans to eat and see the action through fairly large slats embedded into the outfield wall.

But topping it all was the exploding scoreboard.

In 1951, the White Sox had constructed what was then the majors’ largest freestanding scoreboard, placed in the open space behind the single-decked bleachers in center field. It was the classic spare-no-expense scoreboard for the time, with two familiar sponsors: A giant Chesterfield cigarette ad that took up the top half, and a Longines clock that topped the whole thing. But it didn’t make any noise—something Bill Veeck would quickly see to.

Reminded of a play he saw years earlier called The Time of Your Life in which, at one point, a pinball machine ignited into a frenzy of sound, fury and color, Veeck thought: Why not do the same thing with a scoreboard? So he spent $300,000 to revamp the existing scoreboard, adding extra bling such as pinwheels and a multitude of sound speakers. Fans and players who thought it was nothing more than nonsensical décor had no idea what was coming next. On May 20, 1960, they found out. That’s when the White Sox’ Ted Kluszewski launched a home run at Comiskey, and boom—for the next 30 seconds, the scoreboard went nuts. The pinwheels spun, fireworks shot from the top, and a menagerie of sound effects screamed from the speakers. And so it went, every time a Sox player went deep.

Veeck’s scoreboard would not be one-dimensional; it shrieked when a pitcher took too long to make his delivery, groaned when a visiting player hit a home run and, oh yes, it kept score. It even had a “Pitchometer” that would record the speed of each pitch, something that would have been well ahead of its time—had it only been activated.

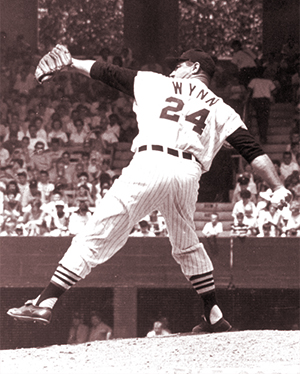

Early Wynn pitches for the White Sox at Comiskey Park during the early 1960s. Note the trees providing a pleasing vernal background through the arches, and the picnic area placed behind the outfield wall for fans to see through. (The Rucker Archive)

Comiskey fans ate up the exploding scoreboard, but reaction was otherwise hostile. “Violent, vehement, extremely noisy,” wrote a dissenting Dan Daniel of The Sporting News. Detroit skipper Jimmy Dykes threatened to protest the scoreboard because the excessive noise startled their players, leading Veeck to respond, “What are we trying to do, make this like tennis?” Cleveland outfielder Jim Piersall, he of Fear Strikes Out fame, called the scoreboard “baseball’s biggest joke” and, after once making a catch to end a game, turned around and heaved the ball at it. The Yankees had a more charming response; when Clete Boyer blasted one over the fence, New York players lined up in front of the dugout and set off a bunch of sparklers. It was noted that the Yankees’ display cost only 18 cents as compared to the $23,000 the exploding scoreboard spent each time it was set off.

Veeck’s lively sideshow magic seemed to rub off on a White Sox team that had been very good throughout the 1950s—but not great enough to supplant the dynastic Yankees. That finally changed in 1959, Veeck’s first full season as Chicago owner, as the Sox finally broke through to their first pennant since 1919—and their last at Comiskey Park. A year later, the coattails of the Sox’ success, combined with the advent of the exploding scoreboard, pushed Comiskey Park attendance to #1 in the American League for the first time since 1917—and the last until after the park closed.

Empty Promises.

Just when it seemed that Veeck was back on top of the baseball world, he had to withdraw from it all. The removal of a bum knee (the result of a World War II injury) and a brain tumor forced him to sell. Chuck Comiskey, who Veeck was nice enough to retain in the front office despite continued legal attempts to gain majority control, tried one more time to buy him out. Again, he failed. At long last, he gave up, and the Comiskey connection to the White Sox and Comiskey Park would henceforth be in name only—and even that would be gone when new owner Arthur Allyn decided to officially rename the venue White Sox Park (though many fans and reporters stuck to calling it Comiskey Park).

Allyn, a local businessman, initially made an honest attempt to spruce up Comiskey Park. He took care of one-long-time peeve by upgrading the clubhouses and moving the visitors’ locker room behind their dugout so they could access it directly—meaning they no longer had to walk through the White Sox’ dugout to get to the showers. But mostly, the reign of Allyn and that of his brother, John—who took over ownership in 1969—was full of empty promises. In 1962, plans were announced to build an exclusive club across the street from the right-field bleachers called “The Coach and Nine” that would be available only to season ticket holders at an annual membership cost of $250—but the project never got past the drawing board. Neither did a plan to build a retractable roof in 1965. In 1968, Allyn was all in on a proposed sports complex that would be built above the railroad tracks just north of Comiskey Park, serving as home to virtually all of Chicago’s pro sports teams. But one by one, the other teams soured on the concept—and Chicago mayor/strongman Richard Daley, also an early advocate, figured that if he didn’t have the power to make it work, no one would.

And so the Allyns were stuck at Comiskey Park. Interstate 90/94 was constructed in the mid-1960s and, along with Chicago’s famed “L” railway, gave fans a more convenient ride to Comiskey with exits and stations just a block or so away. But once they got out of their cars, the walk was scary as the surrounding neighborhood, now a mix of aging factories and low-income housing, brought out a criminal element. The White Sox attempted to fix the situation by lighting up the outside of the ballpark, but all it seemed to do was illuminate the brazen lawlessness taking place on the street. The Sox continued to do their part by winning, but the fans weren’t doing theirs to show up. When the team couldn’t draw a million fans for an exciting 1967 finish to the AL pennant race in which the Sox finished just three games out, Arthur Allyn decided to shake things up. He agreed to play nine home games in 1968 and another 11 in 1969 a hundred miles to the north at Milwaukee’s County Stadium, which the Braves had abandoned for Atlanta a few years earlier. The energy between Sox games at Milwaukee and Comiskey during those two years was like night and day, with an average crowd of 23,500 at the former and only 6,500 at the latter. It didn’t take a rocket scientist to figure that the White Sox’ next move would be a permanent one to Milwaukee—and they might have done it, except that local interests (including future commissioner Bud Selig) bought the bankrupt Seattle Pilots and moved them to Wisconsin for the 1970 season.

Financially challenged, the White Sox became a rotting franchise suddenly playing bad baseball and, after the closing of Pittsburgh’s Forbes Field and Philadelphia’s Shibe Park in 1970, were now playing in the majors’ oldest active ballpark. Money was saved wherever it could be saved. In 1969, the Sox made the awkward move of planting artificial turf on the infield—leaving the real grass in the outfield—and keeping the Bossards, Comiskey Park’s legendary and longstanding family of greenskeepers, from being able to perform their infield magic to trim, harden or soften the grass to the White Sox’ benefit. The exploding scoreboard became too expensive to explode. And the Allyns proved they were no match for Veeck’s promotional genius; the best idea they could come up with was bingo.

Back For Seconds.

Watching the White Sox crumble from afar, Veeck had recovered from his health issues, felt refreshed, and wanted to give Comiskey Park another shot. He rebought the team from John Allyn—who was close to selling to Seattle interests—and immediately went to work. The Comiskey Park name was formally restored, the fake infield grass was torn out, the exploding scoreboard reignited, and an open showerhead was added in the bleachers to cool off fans on a hot day.

Veeck energized two holdovers from the Allyn era to go wild and crazy. Broadcaster Harry Caray, who joined the White Sox in 1971, grabbed the public address mic and crooned Take Me Out to the Ballgame to the fans during the seventh inning stretch, a routine that gained more nationwide fame when Caray split across town to Wrigley Field and the Cubs in the 1980s. And Nancy Faust, the majors’ first female organist who began playing at Comiskey in 1970, taunted visiting teams who were about to lose by performing the 1969 Steam rock hit Na Na Hey Hey Goodbye; the fans began singing along, starting a tradition that would be echoed at sports events worldwide.

Promotionally, Veeck reached new levels of audaciousness. A few times in 1976, he made the White Sox wear shorts—black shorts, no less—to go with white tops with black collars. It had to be the funkiest—and most embarrassing—baseball kit ever worn, and players detested the idea of having to slide in them.

But Veeck truly met his match in 1979 when he held Disco Demolition Night.

The Comiskey Park crowd had always been a rough one. Visiting players complained of having anything and everything thrown at them as far back as the 1950s. When the White Sox tried using a car to shuttle relievers in from the bullpen, it was made a favorite target of fans ready to pelt it. Even Veeck acknowledged the rowdyism, calling Comiskey the world’s largest saloon. But the fans of the 1970s were a whole different animal—more rebellious, longer haired and more apt to take illicit drugs, even at the ballpark. A good many of them also despised disco, the love-it-or-hate-it music craze of the late 1970s, with a passion. So when a Chicago rock station promoter convinced Veeck it would be a good idea to hold Disco Demolition Night, the die for a riotous night at the ballyard was cast. Fans were to bring disco records to a doubleheader, have them stacked in the middle of the field between games and blown up. Veeck was alternately surprised and frightened to see an expected crowd of 15,000 swell to 50,000—all of whom, it seemed, had never seen an episode of Mr. Rogers Neighborhood. Already misbehaving during the first game, the fans went anarchic as soon as the records blew up, pouring onto the field, ripping out the turf and forcing the forfeiture of the second game to the visiting Detroit Tigers.

Disco Demolition Night was hardly the only adventure to put Comiskey Park in peril during the 1970s. A 1976 rock festival held before a packed house on a hot day nearly became tragic when fireworks set off by one of the spectators ignited the upper deck. Thick black smoke rose across the field, but amazingly no one panicked; perhaps they were too busy enjoying the music of Jeff Beck, performing on stage at the moment. Firefighters quickly put out the blaze and the damage was limited to $10,000 and 13 people treated for smoke inhalation. And after Disco Demolition Night rioters made the Comiskey playing field a mess, a couple of rock concerts that quickly followed made it worse. The Bossards did everything they could to mend it, but it was a hopeless venture; players fumed over the war zone-like expanse, which was represented mostly by sand. When the Boston Red Sox’ Dwight Evans pulled a hamstring on the patchy outfield, he threatened to sue the White Sox.

Star-Filled Days.

With such little postseason play taking place at Comiskey Park—even with divisional playoffs expanding the format in 1969, the White Sox only managed one October trip when the 1983 “Winning Ugly” edition bowed to the Baltimore Orioles in the American League Championship Series—the ballpark’s legacy was firmly more focused on three of the more memorable All-Star Games ever played, including the very first one in 1933.

In a sense, Comiskey Park was lucky to host the inaugural Midsummer Classic, inspired by Chicago Tribune sports editor Arch Ward and planned as an add-on to the 1933 Century of Progress Exposition being held in town. It all came down to a coin flip between Comiskey and Wrigley Field; for one of the few times, the White Sox got the better of the rival Cubs and won the toss. The idea was so simple, it was brilliant; take the legends of the American and National Leagues and pit them against each other for fun. Nobody was going to pass on looking out on a field and seeing a galaxy of greats—from Babe Ruth to Carl Hubbell to Jimmie Foxx to Lou Gehrig—all at once. The game quickly sold out and was a massive hit, as the AL triumphed, 4-2.

Two more All-Star Games at Comiskey held their own for thrills and drama. The 1950 game was the first to be nationally televised and the first to go extra innings after the NL’s Ralph Kiner tied the game with a home run in the ninth; Red Schoendienst won it with another homer in the 14th. But it was also best recalled for Ted Williams making a first-inning catch on Kiner’s deep line drive and smashing into Comiskey’s concrete wall in left. Williams played through to the eighth before realizing that something was terribly wrong with his arm; it turned out to be broken, and he missed the next two months, perhaps costing the Red Sox a chance at an AL pennant. In 1983, the All-Star Game celebrated its 50th birthday by returning to Comiskey one last time, with 15 players who performed in that first game on hand to watch; Fred Lynn smashed the first-ever All-Star grand slam, propelling the AL to a 13-3 rout to break an 11-game NL win streak.

Comiskey Park during its last decade in the 1980s. Seen at the back of the upper deck along the first-base side are a series of luxury boxes, added in by owner Jerry Reinsdorf in an attempt to maximize revenue; he soon realized it wouldn’t be enough to save the old yard. (Jerry Reuss)

Jerry’s World.

Disco demolitions and shorts aside, Bill Veeck’s second run as White Sox owner was ill-timed. He was a standout in an earlier generation because his promotions made a difference on the bottom line, but the money had become bigger—much more so after the reserve clause crumbled and free agency took hold in the mid-1970s. Veeck didn’t have the financial backbone to compete, so he sold in 1981 to Jerry Reinsdorf, who oozed “corporate” as a successful real estate and tax attorney magnate. Reinsdorf poured $14 million—close to what he paid Veeck to buy the franchise—into updating Comiskey Park, including the addition of 27 suites in the upper level. He even looked into a full-scale renovation of the ballpark, but the resulting study showed that it would be a financial loser. By then, players began to wonder: Why bother? Ozzie Guillen, the Sox’ straight-shooting shortstop, told The Sporting News in 1989: “(Comiskey Park is) an awful place. We get a lot of young players who come to the big leagues and they look around and they say, ‘That’s big league?’ Everything is so small and old style.”

Reinsdorf agreed. As early as 1985 he began looking at the possibility of closing down Comiskey and moving to a new ballpark. White Sox fans worried about how far away that move might be. By 1988, Reinsdorf told them: St. Petersburg, Florida, if he didn’t get public money to build a new yard in Chicago. In a bizarre series of events on June 30, 1988, the Illinois State Legislature turned back the clock—literally—to avoid a midnight deadline and barely passed a bill at 12:03 a.m. to finance what is now known as Guaranteed Rate Field, sealing Comiskey Park’s fate.

Comiskey Park’s 81st and final year evolved into a worthy swan song. Bobby Thigpen set a record (since broken) by saving 57 games. Carlton Fisk, a White Sock late in baseball life, set another for career home runs as a catcher. A big, young lumbering dude named Frank Thomas showed up late in the season and hit .342 in 25 games at Comiskey. Fittingly, the team so often chided as being “hitless wonders” won a 4-0 home game over Andy Hawkins and the Yankees on exactly zero hits. The Sox finished 94-68—a startling 25-win upgrade from the year before—and surpassed the two-million mark in attendance for only the third time in Comiskey history when a sellout crowd jammed the joint for its final game ever on September 30. White Sox broadcaster Ken Harrelson wore a Black Sox-era cap; Minnie Minoso, the popular White Sox star of the 1950s, carried out the Sox’ scorecard to the umpires. Among the dignitaries present was Chuck Comiskey, the man who never got to own the ballclub his grandfather established. The upper-deck shell of New Comiskey Park loomed over the much smaller first-base side of Comiskey, like the Close Encounters mothership ready to rise above Devil’s Tower. After the White Sox’ 2-1 victory over Ken Griffey Jr.’s Seattle Mariners, Nancy Faust played one last tune: Auld Lang Syne.

Reinsdorf made sure that Comiskey Park would not be completely forgotten; he offered a seat from the old ballpark to every season ticket holder who re-upped for the new one. And the Bossard groundskeeper family transported the Comiskey Park infield dirt, grain by grain, across the street to the new yard.

Like the White Sox, so often in the shadows of the crosstown Cubs, Comiskey Park was the Rodney Dangerfield of ballparks; it got no respect. People always talk wistfully of Wrigley Field, Fenway Park and Ebbets Field in ways that Comiskey could never seem to merit. It was there, almost lost amid the beaten down factories and smelly stockyards of the South Side, providing the best baseball it could. But the baseball wasn’t often so great—again, only one pennant and no championships in the Sox’ final 73 years at Comiskey—but the fans, as rowdy as they sometimes could be, couldn’t blame the ballpark. After all: You don’t last 80 years in spite of yourself.

The Ballparks: Rate Field Approved at the stroke of midnight—give or take a minute—Rate Field was built to be the king of ballparks but became passé within a year, a soulless venue everyone loved to hate with its vertigo-inducing upper deck and refusal to integrate with the neighborhood. Better late than never, the Chicago White Sox took a decade to catch up to the past and have righted some of the wrongs.

The Ballparks: Rate Field Approved at the stroke of midnight—give or take a minute—Rate Field was built to be the king of ballparks but became passé within a year, a soulless venue everyone loved to hate with its vertigo-inducing upper deck and refusal to integrate with the neighborhood. Better late than never, the Chicago White Sox took a decade to catch up to the past and have righted some of the wrongs.

Chicago White Sox Team History A decade-by-decade history of the White Sox, the ballparks they’ve played in, and the four people who are on the franchise’s Mount Rushmore.