THE BALLPARKS

Coors Field

Denver, Colorado

(Flickr—Max and Dee Bernt)

It’s a place where every out is earned and no lead is safe. It comes with a mile-high altitude and a mile-high attitude—or so it is if you’re pitching for the Colorado Rockies and survive the season with a smile and a sub-5.00 ERA. For the fans, the explosion of offense at Coors Field can be as exhausting as the thin air—but just so they don’t miss the ever-changing score, they can walk the main concourse that entirely circles the ballpark and almost never lose sight of a pitch.

(iStock)

Gentrification is sometimes viewed as a dirty word, especially among the more politically sensitive who see that urban tactic as brooming away the underclass to another section of town that, one day soon, will also go upscale and lead to another cold exodus.

But Denver’s Coors Field, home of the Colorado Rockies, is a contrast to that thinking. The LoDo district where the ballpark resides was once an eroding wasteland of long-ago vitality, full of decaying brick warehouses and lightly populated with homeless people milling about with 100-year-old ghosts of gamblers, prostitutes and drunkards. Outside of a few art galleries, design firms and chic, word-of-mouth lounges, LoDo had nowhere else to go but up. Once Coors Field arrived, up it went, stratospherically. There may be no better case study of a ballpark completely bringing a neighborhood back from the dead.

Since Coors Field’s opening, LoDo has exploded with a vibrant collection of restaurants, bars and lounges. An old Piggly Wiggly warehouse, built in 1927, has been retrofitted and houses high-end apartment living. Adjacent is a condo complex that offers rooftop lounging and a two-lane bowling alley. Down the street, a structure of pricey lofts includes street-level sushi and cheesesteak restaurants. Three blocks from Coors Field, the historic Union Station train depot—once LoDo’s architectural anchor—has become a swank hotel run by Dana Crawford, who initially led the community fight against the ballpark. Now she welcomes out-of-town fans. If you can’t beat ‘em, join ‘em.

The pitchers who take the mound at Coors Field could give a rat’s tail about the surrounding aesthetics. They’re too busy fighting for their very lives, in a ballpark that has clearly proven, over and over again, that’s it’s the liveliest ever built for a major league ballclub. It’s not the fault of the structure, the field dimensions, or the wind. In Denver, it’s all about the thin, mile-high air which allows a baseball to travel about 10% further in the air, though your scientist’s results may vary. That means a routine, somewhat deep fly ball traveling 350 feet at any other major league ballpark situated at or just above sea level would go roughly 385 at Coors Field, giving a hitter a 50-50 chance of clearing the fence depending on which direction he hits it.

From the start, the Rockies knew they’d have to back the fences to curtail runaway scoring. That they did, generating the majors’ largest expanse of outfield real estate. As the runs continue to relentlessly pile up, some pitchers think it should be even more expansive, but here’s the problem; while that would cut down on home runs, it would greatly increase doubles, triples, inside-the-park homers and oxygen tank usage for outfielders returning to the dugout exhausted from chasing all those long hits. Damned if you do, damned if you don’t.

Everything’s been done to try and bring major league normalcy to Coors Field. Humidors. Taller fences. Four-man rotations with 75-pitch limits. Home-grown pitchers acclimated to 5,280 feet. But just like the house in Vegas, the thin air always wins.

The page count on all the quotes generated about the ballpark’s wacky offensive nature could rival that of War and Peace. “Pitching at Coors Field isn’t pitching,” said reliever Darren Holmes, “it’s just survival.” “You don’t need an official scorer at Coors Field,” spoke legendary Dodgers broadcaster Vin Scully during a game, “you need a certified public accountant.” Sports Illustrated’s Tom Verducci wrote that choosing to pitch for the Rockies at Coors “is like booking a vacation to Beirut.” “El Diablo,” remarked closer Armando Benitez. (In English, that’s “The Devil.”) Other nicknames invented by the locals included “Chamber of Homers,” “Coors Canaveral” and “Boom Box.”

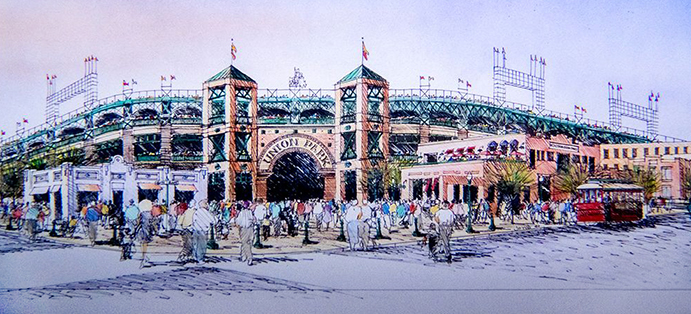

A sketch of Union Park, a visionary ancestor of Coors Field drawn up by local urban planner Karle Seydel before the Rockies were born. Seydel’s renderings would have an influence on Coors’ architect team. (Denver Public Library/Western History Collection/Karle Seydel Papers)

Elevation and bitching aside, there’s no doubt that baseball belongs in Denver, and Coors Field—a red-brick rock of a tribute to its surroundings, a relative no-frills venue with all-thrills action on the field—is the perfect fit for the city and its loyal sports fans.

From Bears to Broncos to Big-League Ball.

That major league representation had eluded Denver for so long was a bit of a head scratcher. Modestly sized at 350,000 residents during World War II, the city grew after the war as telecoms, oil/energy interests and the military industrial complex became big hitters in the local economy. Baseball followed suit on a minor-league level, as Bears Stadium opened west of downtown in 1948 with 18,000 uncovered seats from pole to pole. Fans were eager to come out and enjoy the game; the Bears drew as many as 500,000 annually, at the time outdrawing some major league teams as the franchise was upgraded from Single-A affiliation to that of Triple-A by the late 1950s, serving the star-studded New York Yankees.

Big-league dreams looked to be realized in 1959 when the Continental League was born—and taking the bait, Bears owner Bob Howsam increased ballpark capacity to 25,000, all before the new circuit folded tent in the proposal stage. The venue was expanded even more a year later to welcome the American Football League and the Denver Broncos, and it continued to add seats—changing its name to Mile High Stadium along the way—until maxing out as a transitional 76,000-seat monster in the late 1970s, looking like a sibling to Minnesota’s Bloomington Stadium with its multi-decked left-field bleachers moved in to form a U-shaped configuration for football.

Baseball remained through all of this, as the city’s Triple-A franchise occasionally reminded Major League Baseball what it might be missing with huge crowds—such as the minors’ largest ever when 66,000 filled the stadium on the Fourth of July, 1982. Postgame fireworks had much to do with it, but unhappy major league owners impressed by such crowds (to say nothing of an emerging, rabid fan base for the Broncos during the 1970s) nonetheless took note as Denver became an oft-rumored destination. The closest call took place in 1977 when wealthy oilman Marvin Davis thought he had a deal to bring the Oakland A’s to Colorado—until the City of Oakland reminded A’s owner Charles Finley that the team still had 10 years left on its lease at the Coliseum.

By the 1980s, Denver was in economic shambles as oil became cheap, the Cold War thawed out and the nationwide savings and loan scandal hit the city particularly hard. Office space was one-third vacant, and downtown retail was non-existent. Rather than sit on its hands and hope for the best, the city proactively went about reinventing itself by lobbying for a more diverse collection of new industry while providing the infrastructure for it with a new convention center and a highly ambitious (and highly expensive, at $4.8 billion) airport built in the countryside east of town.

The city also wanted a new ballpark, as it was well aware that the National League was sniffing out new markets for possible expansion. On a kneejerk level, Denver was talked up as a prime candidate—but aging, multi-purpose Mile High Stadium as a long-term solution would be a non-starter, especially with the NL demanding that any new expansion team would need to have a baseball-specific venue built for it.

In April 1990, the six counties that made up Denver’s metropolitan market agreed to place an initiative on a special ballot to build a $100 million ballpark, to be constructed only if the city was given an expansion team. Local politicians did what they could to lean the odds in the ballpark’s favor. They announced that the vote would be held, of all times, in the middle of August, on the 14th—the 42-year anniversary of the opening of Bears (Mile High) Stadium, for all that was worth. And because it was a special election, only registered Democrats and Republicans could vote—shutting out independents who were feared to carry a decidedly anti-ballpark slant.

Early polls ran 2-1 against the measure, but pro-ballpark momentum grew as Election Day approached, then carried into the booths as voters gave thumbs up to the 0.1% sales tax increase to fund the new ballpark by a 54%-46% margin. Curiously, voters within Denver County mostly said no—but the surrounding suburban counties tipped the scale in favor of the new yard.

A year after the voters spoke, so did the National League—unanimously selecting Denver as one of two expansion teams to begin play in 1993.

And all of that was the easy part.

A late addition to Coors Field as the Rockies wanted to up capacity, the Rockpile is situated high above the center-field fence with tickets that start at a single dollar. Bring the binoculars; the closest seat is 480 feet from home plate. (Flickr—Wally Gobetz)

Rocky Mountain Sigh.

Tension and turbulence would be the rule for the next few years as the newborn Colorado Rockies sought out to conceptualize and construct their new ballpark.

First came the site selection; three official locations were considered, including a plot adjacent to Mile High Stadium and another closer to downtown, tucked away next to the tri-school Auraria Campus. But those two sites lacked interaction with the community; fans were likely to drop in, watch the game, then hit the road back home. But the third site, the LoDo district—a collection of ancient, partially abandoned brick buildings—held better promise of urban rejuvenation and a renewed connection between the city and its residents.

Named as such not because it was south of downtown but because it was on land that subtly descended toward the nearby South Platte River, LoDo was where Denver was essentially born, the site of the town’s first railroad station. Industry came and went, but by the 1970s it was all gone, turning LoDo into the city’s Skid Row. A decade later, preservationists paired up with artisans and aspiring businessfolk to refresh the area; a notable early success was Wynkoop Brewing, the city’s first brew pub started by future Colorado governor John Hickenlooper. The LoDo revival crawled along at a baby-steps pace, but its potential was explosive; perhaps a new ballpark could give it that sonic boost.

The Auraria site was the leader in the clubhouse entering the home stretch, but the ballpark district in charge of overseeing Coors Field wisely chose LoDo because it was cheap and it had the opportunity to totally revitalize an all-but-forgotten part of town. The district had some influential supporters; the Washington-based Urban Land Institute lobbied for LoDo, while esteemed New York Times architectural critic Paul Goldberger stated, “If you want to save downtown as a viable place, you have to do things like (build Coors Field)—even though it may seem unconventional and a bit risky.”

Still, the LoDo decision generated angry dissent from all corners. Some thought it would not be wise to displease local, modern-day railroad tycoon Phil Anschutz, who owned the Auraria plot. (He’d be all smiles later when the Pepsi Center arena was built on the site.) Lawsuits came from owners of other sites not considered by the district. And within LoDo, community activists fought tooth and nail against the idea of a ballpark, fearing it would overwhelm and run counter to their own visions of a neighborhood revival.

The “Water Feature” is perhaps Coors Field’s most recognizable non-baseball related sight, consisting of trees and rocks native to Colorado. (Flickr—Paul Dineen)

It also seemed quite odd that a city busting at the seams for major league baseball couldn’t find a hometown big-pockets source to serve as the Rockies’ owner. The team had to initially settle for Mickey Monus, a carpetbagger from Youngstown, Ohio who ran the Phar-Mor discount drug store empire and drew a peculiar resemblance—both in terms of looks and trust—to Jon Lovitz’s ‘pathological liar’ character from Saturday Night Live. Monus’ earlier experience in pro sports was to help start a minor league basketball circuit in which all players had to be shorter than 6’5”; it barely lasted four years. When word got out that Monus was telling companies he’d pull their products from Phar-Mor shelves if they didn’t advertise at Coors Field, everyone in Colorado wanted to give him a one-way ticket back to Youngstown—the residents of which didn’t want him either, after it was discovered he swiped $350 million from his own company and received a 19 ½-year prison sentence for it. Local cattle magnate and Rockies minority investor Jerry McMorris stepped up, axed Monus and garnered enough financial backing to take over as a far more credible team chief.

The Good Neighbor.

The esteemed Kansas City architectural firm HOK Sport (now Populous) gets credit for the visualization of Coors Field, but the ballpark design was actually forged by a healthy bureaucracy of architects, public agencies, advisory panels and a few dedicated local baseball nuts who somehow stuck their feet in the boardroom door and were allowed in to imbue their passions upon the project. Among them was Karle Seydel, a LoDo-based urban planner who long dreamed of a ballpark in the district and had sketched out numerous renderings that looked uncannily similar to what would become Coors Field, including the clock that overhangs the main entrance; and Bruce Hellerstein, an accountant and zealous fan of old-time ballparks who once said he “wanted to be buried under the pitcher’s mound at Tiger Stadium” and stressed the retro look to anyone who’d listen.

Hellerstein and Seydel didn’t have to twist HOK Sport’s arms to convince it to develop an old-style design for Coors. HOK was already basking in the glory of Baltimore’s Oriole Park at Camden Yards, an absolute game-changer in ballpark architecture with its nostalgic makeup, vintage downtown views and asymmetrical outfield. It was a no-brainer to approach Coors Field, surrounded by century-old brick buildings, with similar perspective. “In planning and design, we were careful about the spaces beyond the ballpark walls,” wrote HOK Sport chief architect Joe Spear. “We thought about how the ballpark could be a good neighbor; how we could make it feel accessible and approachable to pedestrians; and how we could connect the ballpark in an authentic way to existing structures in the district to inspire eventual development.”

While Spear provided the big picture, Coors Field designer Brad Schrock dug into the weeds and helped give the ballpark its true, distinctive personality. Schrock intensely studied LoDo, walking the area over and over again, taking hundreds of pictures and soaking up the neighborhood to find the right inspiration. He settled on a design that, at first glance, appeared to be a typical retro ballpark mix of red brick, sandstone and exposed dark green steel topped by an arched lattice treatment. But there were also decidedly local touches, such as the semi-circular signage that surrounded the main entry clock as an ode to nearby Union Station, and the tight curvature of the main gate that evoked Denver’s historic Brown Palace Hotel. To give the ballpark an added distinctive touch, Schrock hired local artist Barry Rose to produce 55 glazed terra cotta columbines (Colorado’s state flower) that adorn the top of each pilaster on the outer structure. The columbine is also represented with two large murals illustrated upon the sidewalk at the first base gate along Blake Street.

The building of Coors Field generated a new round of headaches. Many properties were condemned to make way for the ballpark, but one stubborn holdout was a family that owned pivotal land where the front entrance would be constructed. It asked for $3.5 million; the ballpark district countered with $1.5 million. The two parties settled somewhere in in the middle. To secure a beautiful, open view of the Rocky Mountains behind the left-field corner, the district then had to furiously discourage expansion of a nearby power plant and construction of an elevated rail platform. Denver officials also got into it, threatening to halt 11th-hour construction unless the district pitched in for traffic upgrades around the ballpark. The cost of Coors Field drove up to over $200 million from the initial pre-vote estimate of $75 million, with over $500,000 alone spent on legal fees.

A row near the top of the upper deck is painted purple. Why? Because it’s the point in Coors Field that’s 5,280 feet—or exactly one mile—above sea level. (BigStock)

We’re Going to Need a Bigger Ballpark.

As Coors Field was busy being built in 1993, the Rockies began play at Mile High Stadium—where bottled-up enthusiasm for big league ball erupted like soda shooting out of a Mentos-fueled bottle. The Rockies drew a record-shattering 4.48 million fans, an average of 55,000 per game, and a year later were on pace for nearly 4.7 million when the players’ strike shut the game down in mid-August. These staggering numbers had the Rockies rethinking whether 43,800 seats at Coors Field were going to be enough, and so they asked the district for more. That’s fine, said the district, so long as you pay. That’s fine, said the Rockies, and so they extended the three-deck setup around the right-field foul pole to well beyond right-center, adding 4,000 seats. Joe Spear and HOK Sport, fearing the ballpark’s charm would be diluted, desperately tried to lobby the Rockies against the expansion to no avail.

Additionally, another 2,300 seats would be added in a separate bleacher section with a rounded top end high above the center-field batter’s eye. The Rockpile, as it’s lovingly called, is a collection of cheap seats in more ways than one; the closest seat is 480 feet away from home plate while the farthest is another 100 beyond that—and today the tickets for these seats remain among baseball’s lowest priced, at a single dollar for people over 55 and children under 12, while it’s four bucks for everyone else. No hitter has ever reached the Rockpile, though Mark McGwire once struck the facing of it in batting practice.

Empty seats would not be an entirely absent notion when Coors Field opened for the masses. For the very first game at Coors—a “trial run” exhibition against the New York Yankees—2,700 tickets went unsold and variable accounts had the actual crowd count as much as 10,000 below capacity, perhaps in part because replacement players were being used on what would turn out to be the final day of the 1994-95 work stoppage. When the true players returned, the official first game at Coors still fell 3,000 shy of a sellout, but those who showed up braving late-winter elements—a first pitch temperature of 39 degrees followed by occasional flurries—were treated to quite an opening act. In a seesaw game, the visiting New York Mets took a 7-6 lead in the top of the ninth; the Rockies tied it in the bottom half; the two teams exchanged a run in the 13th, with the Mets notching another in the 14th. Finally, Dante Bichette put an end to the proceedings with a three-run homer—the first by a Rockie at Coors—to win it, 11-9.

Non-capacity crowds continued to be something of the rule early in the Rockies’ inaugural campaign at Coors Field, perhaps a consequence of anger over the senseless, strike-induced loss of so much baseball in the previous year. But by June, as Rockies fans began to sense that the team was emerging from their early expansion struggles with a winning record that would ultimately take them to the postseason as a wild card, Coors Field never drew another crowd under 48,000 for the rest of the year.

In the one spot within Coors Field where the circular main concourse doesn’t have a view of the playing field, fans are instead treated with a 140-foot-long mural depicting the history of Denver’s LoDo district, where the ballpark is located. (Flickr—Paul Dineen)

Hiding in Plain Sight.

Coors Field drew immediate raves for its visual purity, with no gratuitous displays of mallparkism. That didn’t mean the ballpark was devoid of unique features and divergent points of interest. There was, for instance, the purple row of seats six rows from the top of the upper deck, painted as such to denote the point at Coors that’s exactly one mile above sea level. In terms of perishables, there was (and still is) the Mountain Ranch Bar and Grille, a full-fledged restaurant with indoor and outdoor viewing tucked away in the corner of the second deck near the right-field foul pole. Under the bleachers behind the right-field fence is the Warning Track Party Room, which groups of up to 90 people can rent out, enjoy a catered buffet, and breathe on the backs of right fielders.

But perhaps the most stylish perk at Coors Field is the one you never see on TV. The SandLot, located on the field level near the right-field corner, was the first microbrewery located within a major league ballpark—and it wasn’t just churning out generic swill. One of its first creations was Bellyside Belgian White, which soon changed its name to Blue Moon—giving birth to a popular brand brew. Just as intriguing is how the SandLot came to be; it’s the only pre-Coors structure within the ballpark’s property to survive, a five-story warehouse built in 1913 that originally was to be demolished before the architects and preservationists decided it would be more conveniently charming to fuse it into the ballpark structure. It’s a tactic that wasn’t lost on HOK Sport when they envisioned the Western Metals Building as part of San Diego’s Petco Park a few years later. The SandLot has an entrance off of Blake Street that suggests that it’s open year-round—but alas, it’s not.

One of Coors Field’s more promoted features is a field-level concourse that fully encircles the field, allowing fans to see the game without any structural interference. Except that’s not exactly true; there is a walled obstruction as you walk through a tunnel under the Rockpile in center field. But to keep you from getting bored, one side of the tunnel contains a 140-foot-long, 1930s/WPA-style mural entitled The West, The Worker and The Ball Field by Jeff Starr and Matt O’Neill. The artwork heroically depicts, chronologically from left to right, the history of LoDo from the first railroads to construction workers building the ballpark to Rockies players hitting away.

Other, more unique displays of art can be found outside of Coors Field’s gates. On the outer wall of the SandLot is Erick Johnson’s Bottom of the Ninth, a colorful neon depiction of a runner sliding into home through multiple motions as the catcher and umpire await. On the other side of the ballpark, gracing a pedestrian overpass toward the Left Field Gate, is a charmingly goofy pop-art arch entitled the Evolution of the Ball by Lonnie Hanzon. The 42-foot-wide artwork shows creativity at a premium, with 108 tiles each featuring a different type of ball—including a baseball, eyeball, crystal ball…and yes, Lucille Ball.

Coors Field’s most recognizable display to fans and TV viewers is the large-scale diorama of a rocky mountain scene behind the center-field fence, wedged in between the left-field bleachers and bullpens in right-center. It includes actual trees, plants and rocks native to Colorado, giving the ballpark appropriate regional character; in 1997, it was given liquid action with the addition of three 10-foot waterfalls, a pond and seven fountains that shoot water 40 feet into the air before the first pitch, after a Rockies home run, during the seventh-inning stretch and after the final out of a Rockies win—all so long as there’s no drought in progress.

Coors Field is home to the majors’ most spectacular sunsets. That’s the cool part; the hard part is the glare fans seated down the right-field line have to battle just before the sun sets. (Flickr—Kari)

The Hit Parade.

One form of drought that Coors Field will certainly never experience is that of hitting. Mile High Stadium fired the warning shot for the offensive madness that was to come at Coors when the Rockies’ temporary home of 1993-94 produced high-octane numbers for the daily box scores. Despite the Rockies’ efforts to move the fences back and not turn Coors Field into a pinball machine, the pitchers still go “tilt” more often than not.

It’s true that Hideo Nomo actually threw a no-hitter at Coors for the Los Angeles Dodgers in 1996, the only one thrown to date at the ballpark. Here’s another fact you probably didn’t know: In nine other starts at Coors, Nomo’s ERA was 9.67. To paraphrase Blondie: One way or another, the thin air is gonna get ya.

Ask Bryan Rekar. A top draft pick by the Rockies in 1993, Rekar made it to the Show in 1995. He lasted three years in a Rockies uniform, making 15 starts at Coors Field. After a 10.16 ERA in those outings, he was sent to Tampa Bay—likely accompanied with a medical note advising the newborn Devil Rays to up their budget for shellshock rehab.

Rockies pitchers in general have always struggled with the mile-high elements at Coors. In eight of their first 10 years at the ballpark, the Rockies’ posted the National League’s worst team ERA; in the other two years, they were next-to-last.

Maybe the talent level wasn’t good enough, the Rockies thought. With abundant revenue streams buoyed by one sellout after another at Coors, the team had the means to tap into the free agent market and lure star pitchers into the fold. Darryl Kile, Mike Hampton and Danny Neagle—all superb arms coming off impressive tenures with their previous clubs at sea level—signed on with Colorado between 1998-2000 to tame the beast. The beast won. Kile was 21-30 with a 5.84 ERA in his two years at Denver. Hampton was 21-28 with a 5.75 ERA over his two years. Neagle was 19-23 with a 5.58 ERA in his first three years of a five-year contract; he was injured the fourth year and released before the fifth after being caught drunk with a prostitute, proving that the Coors Field effect works in many ways. All of this sent a clear warning to top free agent pitchers: Avoid Colorado.

As miserable as Coors is for the pitchers, it’s been pure bliss for the hitters. One look at the home/away splits for Rockies players plainly exposes that they hit like Mickey Mantle at home and Mario Mendoza on the road. It’s a Jekyll-Hyde routine that’s evolved into a justifiable perception that the ballpark inflates their numbers—handicapping the Hall-of-Fame chances of legit Colorado batting stars like Larry Walker and Todd Helton.

Coors Field’s offensive output through its first eight seasons was particularly jaw-dropping. The Rockies routinely hit over .310 at home in each of those years, peaking at a stunning .343 in 1996—the same year they scored 10-plus runs in 29 of 81 home games. Dante Bichette and Andres Galarraga each averaged over an RBI per game at Coors during their extended Colorado tenures; Galarraga, in 1996, knocked in 103 runs just at home. The 1998 All-Star Game was held at Coors—and to no one’s surprise, it was the highest scoring ever as the American League outlasted the National League by a 13-8 count.

The insanity peaked in 1999. Coors Field yielded 303 home runs, the all-time season record at a single ballpark. The Rockies’ .325 home average was significantly raised thanks to Walker’s remarkable .461 clip. (In fact, Walker hit .418 at Coors from 1998-2001, and for his entire career at the yard batted .381.) Colorado’s home ERA was an atrocious 7.11, and of the 1,028 overall runs they gave up—the most by a NL team since the infamously pitching-inept 1930 Philadelphia Phillies—626 were allowed at Coors. Then there were the “Coors Field Specials”—10 of them during 1999—in which both the Rockies and their opponents scored 10 or more runs in the same game. One of those, played on May 19, is perhaps the craziest ever at Coors; the visiting Cincinnati Reds came in and pounded the Rockies, 24-12, in a contest that included 43 hits (28 by the Reds), 11 doubles, nine homers (including three by the Reds’ Jeffrey Hammonds), 15 walks, and a major league-record 81 total bases. Colorado manager Jim Leyland, the crusty veteran who just two years earlier had piloted the Florida Marlins to a World Series title, nearly chain-smoked his way out of human existence after the 1999 experience; he took five years off before returning to the dugout with the Detroit Tigers.

In 2014, the Rockies reconstructed the upper deck behind right field and installed the Rooftop, an interactive collection of bars, eateries and lounges for fans who want to do more than just watch baseball. (Flickr—Ken Kanouse)

The Humidor! The Humidor!

What architects, front office wizards and All-Star pitchers could not do to tame Coors Field’s hitting madness, the team engineer could. In 2002, Tony Cowell went on a hunting trip and noticed at one point how his leather boots dried up and hardened from outdoor moisture. At that point he thought to himself what would happen if he did the same thing to a baseball, which was also made of leather. So when Cowell went back to work, he tried an experiment: He dropped two balls—one stored away in a moisture-sapping humidor, the other not—from the top of Coors Field to a concrete walkway below to see if there was a difference. Sure enough, he found that the ball from the humidor had less spring to it.

The Rockies bought into Cowell’s science and used a spare storeroom under the stands to install an industrial-strength humidor, one that the Denver Post’s Nick Groke described as looking like a “beer keg refrigerator.” All game balls would be placed there before the first pitch; even though its usage wouldn’t bring Coors Field baseball down to sea level, the results were still noticeable enough. Ballpark batting averages dropped below .300 for the first time; home run totals, which had typically tallied around the 250 mark, settled into the 160-180 range. In 2005, Coors Field’s 11th year, the ballpark finally witnessed its first 1-0 game when the Rockies edged the San Diego Padres; the 847 games before that was the longest streak without such a result at any ballpark, ever.

By then, the ball wasn’t the only thing that had hardened in Denver. Rockies fans, tiring of the constant losing—the team had only one winning season between 1998-2006, and that was a .500-skimming 82-80 mark in 2000—began staying home. League-leading attendance had eroded to such a point that by 2005, the Rockies drew just 1.9 million fans to Coors Field—ranking them 26th out of 30 major league teams. Announced crowds of 20,000 looked to be half that.

The decade-old ballpark wasn’t the problem, even if little had been done to entice more fans. The Rockies had, in 2005 erected their first statue at Coors featuring a generic ballplayer in front of the main gate entitled “The Player” accompanied by the Branch Rickey quote, “It is not the honor that you take with you but the heritage that you leave behind.” Also, the city’s emerging light rail system had arrived near Coors at the old Union Station, making it more convenient for fans to avoid parking in LoDo. While all of that was nice and good for the fans, they just wanted to see winning baseball.

In 2007, they got their wish.

Rocktober and Beyond.

For much of the 2007 campaign, the Rockies were teetering around the .500 mark—and that was looking to be a moral victory for a ballclub stuck on 90-something losses the previous few seasons. But in mid-September, something kicked in. The Rockies won and kept winning, losing just once in their final 14 regular season games. They forced a 163rd game at Coors against the Padres to determine the NL’s wild card entrant and, in perhaps the most thrilling game ever played at the ballpark, survived a 9-8, 13-inning battle to make their first postseason appearance in 12 years. The return of sellout crowds and enthusiastic fan support fueled an incredible momentum into the playoffs, as the underdog Rockies swept both the divisional series against Philadelphia and the NL Championship Series against Arizona to gain their first-ever pennant. Then came the team’s biggest foe: Downtime. The Rockies cleaned up on the Diamondbacks so fast, they were forced to sit for eight days before the start of the World Series; once Game One rolled around, a cooled-off Colorado team was beaten down in four straight by the Boston Red Sox, still in a groove with far less rest after a seven-game ALCS triumph over Cleveland.

Still, the Rocktober experience rejuvenated both franchise and fandom. Annual attendance returned near the three million mark. A new wave of bashers donned the purple and black, including Gold Glove shortstop Troy Tulowitzki, and outfielders Matt Holliday and Carlos Gonzalez.

Most importantly, there would be true, well-adapted pitching within the Rockies’ staff. Ubaldo Jimenez gave the team a brief burst of ace-level output, using a 100-MPH fastball in 2010 to gain a start in the All-Star Game and falling just a win shy of becoming the Rockies’ first 20-game winner. Meanwhile, a more persistent presence developed in Jorge De La Rosa, a rare case of a pitcher who actually performed better at Coors Field thanks to a breaking ball he mastered more accurately at 5,280 feet. On the surface, De La Rosa’s career Coors ERA of 4.31 may not be anything to wow over, but he knew how to win—as his 53-20 home record firmly reflects.

While maintaining a winning culture continued to be a challenge on the field at Coors Field, the surrounding LoDo district had long since staked its claim as a smashing success in response to the ballpark’s presence. When Coors opened, many restaurants, bars and lounges followed suit and gave the area a feeder mentality that benefitted arriving fans. In terms of housing, the area has seen exponential growth from the mere 270 housing units that existed before Coors. Some of the dives that long predated Coors have survived and thrived; this includes Herb’s Hangout, a blues and jazz bar which opened in 1933 and, two blocks from the ballpark, caters today to a far more upscale crowd than the morbidly eclectic mix of drunks, felons, future felons and beatniks (including, it was said, the famed Jack Kerouac) who frequented the joint in more perilous times.

The Rockies sensed the lively pre- and postgame activities outside of Coors Field and thought, hey, let’s try and tap into it. So in 2014, the team reconstructed the upper deck behind right field, removing all but the lower five rows and installing behind them The Rooftop—a two-level, open-air lounge complex with several bars, a Smashburger restaurant, patio space and plenty of standing rails for fans to enjoy the game and chill with friends. The Rooftop reflected two ballpark trends of the 2010s: Less seating to increase ticket demand, and a lounge experience for younger fans who prefer to do more than just sit and watch a game. For an inexpensive fee, you can get a standing room-only ticket for the Rooftop that includes a food/merchandise credit; you not only get a glimpse of downtown Denver from inside the ballpark, but also a premium view of the Rocky Mountain sunsets than often turn the horizon gold as the first few innings of summer play pass below on the field.

More ambitiously, the Rockies are jumping into another popular venture among MLB teams: Real estate. Behind the third-base side of Coors Field, across 20th Street, a surface-level parking lot is being torn up to make way for McGregor Square, a mixed-use development that will include three 13-story buildings surrounding an open-air plaza and containing residences, office space, a hotel and retail. Named after former team president Keli McGregor (who died in 2010 at age 48), McGregor Square is due to open in 2021 and provide the Rockies with more revenue while adding cutting-edge vibrancy to the LoDo district.

While on the subject of revenue, the Rockies also opened Coors Field for other events starting in 2015 when the Zac Brown Band performed before a crowd of 42,000. The obligatory outdoor hockey games have also been held at Coors, with the first two such games played just a week apart in 2016: A college matchup between the University of Denver before 35,000, and a National Hockey League contest between the Colorado Avalanche and Detroit Red Wings which drew an impressive crowd of 50,095 to the ballpark.

A rendering of McGregor Square, an ambitious multi-use complex adjacent to Coors Field that the Rockies are building—and will profit from. Due to open in 2021. (Stantec)

The Hits Just Keep On Coming.

The third oldest NL ballpark behind Chicago’s Wrigley Field and Los Angeles’ Dodger Stadium, Coors Field is ensured of at least a 50-year lifespan thanks to a new lease that will keep the Rockies at the ballpark through 2047. This, of course, will produce more salivation for hitters and more headaches for pitchers.

Through its first 25 years of existence, Coors Field has wrung out more three-homer games, cycles, and pitchers bludgeoned for 10 or more runs than any other ballpark. Unless Denver sinks toward sea level, more Coors Field Specials are bound to happen as both the Rockies and their opponents run up the score past 10 runs each. Visiting players will continue to hope that the live yard will provide slump-busting fodder for any hitting funk they may be experiencing. An occasional record will fall in favor of a new one, which itself will eventually be broken by another. Witness 2019: The Rockies and Padres—the same two teams who gave Coors its first 1-0 game 14 years earlier—paired up to score 92 runs on 131 hits, both numbers breaking records for a four-game series. Don’t be surprised if, someday, the Rockies group together with another team to reset the mark. Try hard as it might, there won’t be a damn thing the humidor will be able to do about it.

The grousing of pitchers aside, there’s simply no complaining about Coors Field. It’s a solid, unpretentious masterwork of retro baseball architecture, with enough perks and quirks to give it charisma without poisoning the ballpark’s authentic nature. Its perfect blending into the neighborhood has given a once-derelict section of Denver an energetic rebirth.

The hits just keep on coming at Coors Field—but the biggest hit has been, and always will be, the ballpark itself.

Colorado Rockies Team History A decade-by-decade history of the Rockies, the ballparks they’ve played in, and the four people who are on the franchise’s Mount Rushmore.