THE BALLPARKS

T-Mobile Park

Seattle, Washington

Chances are, there’s a thesaurus out there that lists Seattle as a synonym for the word “rain.” Perception does not always equal reality; outside of California and Arizona, Seattle is the driest major league city during the baseball season. But at T-Mobile Park, a retractable roof stands at the ready—just in case.

The Seattle Mariners hosted two home openers in 1999, though diehard baseball fans of the Emerald City insist there was really only one—and it wasn’t Opening Day at the Kingdome in April. For when T-Mobile Park opened for the masses in July, allowing spectators to breathe real oxygen while taking in true blue skies, the maligned Kingdome was quickly reduced to a mere memory—and, less than a year later, pure rubble.

The Seattle Mariners hosted two home openers in 1999, though diehard baseball fans of the Emerald City insist there was really only one—and it wasn’t Opening Day at the Kingdome in April. For when T-Mobile Park opened for the masses in July, allowing spectators to breathe real oxygen while taking in true blue skies, the maligned Kingdome was quickly reduced to a mere memory—and, less than a year later, pure rubble.

Itching to hurry Seattle baseball back to the great outdoors, the Mariners pressed to conceive, design, construct and open T-Mobile Park in under four years—retractable roof and all. It was an amazingly short time frame from the first sketch to the last swipe of paint, all the more satisfying to Seattle baseball fans starving an eternity for such a ballpark.

A deliberate mix of architecture ranging from nostalgic brick façades to commanding steel cross-structures and topped by an immense, spine-laden retractable roof that seems inspired from Captain Nemo’s Nautilus, T-Mobile Park makes for an imposing presence against the compact yet towering skyline of downtown Seattle. Drivers taking the main ballpark exit off the hillside freeways towards the ballpark feel more magnetism than invitation, as if being sucked straight into the right field grandstands. But there are enough openings of various shapes and sizes within T-Mobile Park to allow off-ramp users to capture tantalizing glimpses of its interiors, making the experience one of exhilaration, not intimidation.

Once down on the streets surrounding T-Mobile Park, yesteryear is still in vogue. Age-old warehouses and the like hold sway, some still in service, some abandoned, others beginning to house a growing tide of hi-tech boutiques. Just a few blocks to the ballpark’s west, the Port of Seattle with its giant shipping cranes—a major influence on T-Mobile Park’s architectural design—continue at the same brisk pace that it has for decades. Telephone poles stand unevenly and traffic lights still dangle on wires here and there above streets that are in need of repair and have no regard for zoning laws. Quite simply, the area has “unincorporated” written all over it.

Nothing like nostalgia to surround a state-of-the-art baseball facility.

Until the inevitable invasion of modern development (none of which have yet to threaten T-Mobile Park’s beautiful upper-level views of Elliott Bay and the Olympic mountains), the Mariners feel at home in their new neighborhood, taking quality strides to wrap the ballpark with local echoes of the past.

Every aisle-facing seat, for instance, carries on its side paneling the image of Fred Hutchinson, a Seattle native and teenage star for the Pacific Coast League’s Seattle Rainiers prior to a 20-year career in the majors, half of them as manager. Hutchinson died of cancer in 1964, three years after guiding the Cincinnati Reds to his only pennant; today a cancer research facility in Seattle is named after him.

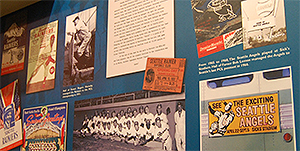

Other various art displays throughout the ballpark speak of the city’s baseball past, and a museum on the first level focuses on the sport’s history throughout the Northwest region. All of this to remind T-Mobile Park patrons that Seattle baseball doesn’t start and end with a Mariners franchise born in 1977.

A Short Marriage.

Seattle’s first go at the majors didn’t go so well. The 1969 Pilots played in a decrepit minor league facility, their only sellout taking place after the season when the owners, bankrupt, allowed a group of investors to buy the team and move it to Milwaukee (where they are now the Brewers). Local and state politicians had anticipated a slightly longer stay for the Pilots but trudged on with their plans to build a modern, multi-purpose stadium. By the time construction crews put the final touches on the Kingdome in 1976, Major League Baseball gave Seattle a second chance and, a year later, the Mariners took the field for the first time.

At first viewed as a savior, the Kingdome gradually began to grow weary on its tenants and fans who frowned upon its depressing, gray aesthetics. After all, the local weather gave Seattleites enough of that. Compounding the Kingdome’s growing reputation for the Mariners was another problem: They weren’t winning. Over their first 14 years they suffered 14 losing seasons, never finishing higher than fourth in the seven-team A.L. West. “I thought you were in Seattle for the Mariners,” TV’s Frasier Crane once queried Sam Malone, ex-Cheers bartender, ex-Red Sox pitcher. “Believe me,” insisted Malone, “no one comes to Seattle for the Mariners.”

The Kingdome and the losing became a bad combination for the M’s, and a series of regimes grew restless at the situation. Of course, they blamed the stadium more than themselves.

Inside the main rotunda is a spiraling, chandelier-style collection of 1,000 bats created by local artist Linda Beaumont to welcome fans before they walk upstairs to the main concourse. Seattle Times art critic Robin Updike said that the display was “very likely the most remarkable piece of public art ever installed in a sports facility.”

Local and state government initially answered back at the Mariners, with its arms outstretched, “C’mon, we just built the thing for you.” The Mariners understood that the argument to leave a relatively young facility for a baseball-only park would be a tough one, but then in 1994 a gift fell into their lap. Actually, it fell into the laps of Mariners fans in the form of ceiling tiles that had broken off from the Kingdome’s roof. Stadium officials saw a quick fix; the Mariners saw a building falling apart.

The tile incident added muscle to the Mariners’ leverage and justification to get out of the Kingdome, ASAP. Early in 1995, the team ownership set the political wheels in motion for a new ballpark. The state legislature in Olympia agreed to authorize a vote of King County residents to decide the matter—a lukewarm victory for the Mariners, who were hoping to bypass such a vote and move the project along faster with legislative approval only. It was May; the vote would be in September.

Concern draped the Mariners throughout the campaign, which saw public opinion polls knocking the measure down by double digits.

Just as it appeared locked in for defeat, an amazing thing happened.

The Mariners found themselves in a pennant race.

Once on the main concourse after entering through the main rotunda, fans walk upon a nautical mosaic featuring the signatures of Mariners players on the roster for T-Mobile Park’s first home game in 1999.

There Ain’t Nothing Like Winning to Boost the Polls.

Struggling through much of the year and trailing by 13 games as late as July, the M’s caught fire like never before and began to chisel away at a first-place California Angels team stuck in neutral. Seattle sports fans rediscovered the long-lost comprehension of a Mariners postseason and dared to return to the Kingdome in large numbers. Crowds of 40,000 and 50,000 were suddenly commonplace; the city was in love with its baseball team for the first time, ever. It was the best PR a ballpark initiative could possibly ask for.

Alas, the vote came too early. There was optimism as the booths closed on Election Day, September 19, with the ballpark measure appearing headed for a slim victory. But then the absentee votes, likely checked weeks earlier when Mariners Fever was in its incubation stage, were counted—and the balance was tipped.

The measure lost, 50.1% to 49.9%.

The loss at the booth didn’t dampen the Mariners’ spirit on the field, winning 17 of their last 22 games—including a tiebreaker playoff against the Angels that gave Seattle its first-ever divisional title. The momentum carried into the playoffs, with the M’s knocking off the storied New York Yankees in a sensational five-game series, before finally succumbing to the Cleveland Indians in a taut, six-game ALCS.

It’s All About the Timing.

Back at Olympia, there was a change of heart fueled by pennant fever. In a special session lasting three days, the Legislature did an about face on its previous stand and decided to okay the ballpark itself. It gave the Mariners their prize with the belief that had the vote been taken a few weeks later, enough people would have jumped on the team’s bandwagon to approve the measure.

Every aisle-end seat at T-Mobile Park includes an engraved sketch of former major league pitcher Fred Hutchinson, a Seattle native and local hero who died of cancer in 1964 at age 45.

Mariners fans, both long-suffering and recently-converted, thrilled at the legislature’s action as the right thing to do— while many who punched out “No” at the booth felt that their voting voice had been undermined.

The Mariners initially wanted HOK Sport, the Kansas City architectural firm that had given baseball Oriole Park at Camden Yards, to design the new ballpark. But it wasn’t their choice; Olympia’s deal called for the creation of the Public Facilities District (PFD), which would physically and fiscally oversee all aspects of the new ballpark. Its seven-person board, made up of council members from the City of Seattle and King County, decided to go with the architects next door: Seattle-based NBBJ.

Established during World War II, NBBJ would spend its first 40 years retaining a conservative, regional image for itself, developing a large niche in the health care industry. By the 1980s it began to reach out worldwide and take on more challenging projects; its success in doing so made it the second largest firm in the United States, fifth around the world.

Still, the awarding of T-Mobile Park to NBBJ raised eyebrows, due to the firm’s relatively skimpy portfolio of sports facilities. But the PFD was impressed with the one ballpark contract NBBJ recently had won: Miller Park in Milwaukee.

From the upper-deck concourse along the left-field line, T-Mobile Park spectators are granted spectacular views of downtown Seattle, the massive shipping docks and the Puget Sound sunsets beyond.

What the Architects Were Thinking.

“Miller Park was very compelling to the PFD, because Milwaukee was very different from all the other new ballparks,” said Dan Meis, one of the principals for the then-fledgling sports and entertainment branch of NBBJ that had recently opened in Los Angeles. “The PFD had a respect for the fact that we were a very design-sensitive organization, and we really wanted to make (T-Mobile Park) an incredible civic building.”

“It was the combination of being the home team with the design and sports knowledge that we were bringing from L.A. It was a very interesting mix to the PFD.”

Instinctively seduced with a Camdenesque setting for the new ballpark—not to mention close proximity to downtown and mass transit—the PFD’s initial choice for the ballpark site was within the historic Pioneer Square district, just a few blocks north of the Kingdome. But upon closer inspection, NBBJ discovered that placement of a retractable roof—a non-negotiable absolute—would require the permanent closing of several streets. Even if this were allowed, the ballpark would still be a tight fit, leading to field dimensions even shorter than the Kingdome’s. Most everyone complained, from Mariners fans burning out on double-digit slugfests to the many gallery owners in the neighborhood who worried of art patrons staying away on game day. Unable to will more square footage for the area, the PFD eventually soured on the site as well.

The focus quickly turned to another site, this one two blocks south of the Kingdome. Though it was less romantically located—mixed in with a more industrial ambiance—the site offered more territory and more freedom to modify the areas immediately surrounding it. With nothing else better to offer, the future home of T-Mobile Park was approved.

NBBJ’s initial challenge was to design a ballpark that would combine two distinct architectural styles: the charm and composure of Pioneer Square, and the rigid, steely nature of the nearby seaport. In what would seem a fit of design schizophrenia, NBBJ chose to separate the styles within Safeco Field rather than force a hybrid. But it would work to the ballpark’s advantage.

With railroad tracks and existing industry limiting potential spectator flow from the east, NBBJ concentrated on setting up the main entrances to the west. Rising four stories from the sidewalk and displaying ample window space surrounded with a healthy representation of brick, the west facade of T-Mobile Park emits a more personable character, drawn from intense studying of nearby Pioneer Square buildings.

On the other side, it’s the industrial age all over again. Steel girders crisscross one another to form trestles and two tracks, holding the roof in its retracted position up to 250 feet beyond the boundaries of the ballpark—and high above a series of railroad tracks. In the event one of the trestles is taken out by a runaway train, a massive wall measuring 16 feet thick stands guard at its base.

A freight train strolls underneath the T-Mobile Park roof, which stretches over the main artery of railroad tracks headed through Seattle. Massive concrete bases between the tracks prevent a runaway train from doing major damage to the roof supports.

The roof originally was set to extend and shelter the entire ballpark structure, but rising steel prices forced a redesign that would reduce the roof’s coverage by 25%. Though all seats would remain protected, the roof would no longer cover the far west end of the facility—and lead to other design changes, the most significant of which would be the erasure of a lighthouse structure at the northwest entrance that would have served as a “beacon” for arriving fans.

Redesigned, the roof in its retracted state outside of the ballpark’s bowl would allow many fans to enjoy a game on a sunny afternoon or beautiful evening without even realizing that the roof is there, in contrast to the omnipresence of opened roofs at other ballparks.

One of T-Mobile Park’s more eye-catching art displays is the use of recycled materials to recreate team logos (or “quilts”) of every major league team, such as this one for the Mariners. Art by Rose Palmer Beecher.

The mandatory inclusion of the retractable roof led many in the Seattle area to wonder: Why a roof at all? That may seem like a funny question to outsiders who imagine Seattle as a gray, rainy place, yet the truth is that most of its precipitation falls during the fall and winter. Even when it does get wet during the baseball season, it’s usually in the form of light showers, as opposed to the vicious summer downpours at ballparks east of the Rockies that send grounds crews scurrying to unfurl the tarps. (The roof did pick a fine time, during a rare deluge at a game in July 2000, to ignore the operator’s command to close.)

Ballpark Politics Bablyon.

In the end, the original opening date of April 1999 was missed by three months. That it got finished at all anytime in 1999 was something to stand up and applaud about. But left behind in the trail to fruition lay a string of headaches and strained relationships.

There was the Mariners’ threat, on the eve of groundbreaking, to sell the franchise—convinced that certain PFD members were trying to delay or even scuttle the project. Slade Gorton, the Washington state senator who more than anyone else had kept baseball alive in Seattle over three decades, eventually got the two sides to smoke the peace pipe.

There was the grass roots movement, asking to halt construction and demand a new ballpark vote; it didn’t get its wish, but they succeeded in delaying T-Mobile Park’s opening to mid-1999 when the PFD, awaiting an opinion from a backed-up state Supreme Court, had to put the project on hold for several months.

There was La Nina, the weather phenomenon that caused havoc with ballpark construction just as it was entering a hectic home stretch during the winter of 1999. Battering Seattle with wind and rain—100 straight days of measurable rain at one point—the stormy climate caused construction to fall a month behind. To make up, crews practically worked 24/7 as the Mariners insisted they finish the job by July—translating to lots of overtime pay and the blowing out of the water of the ballpark’s revised $417 million budget, itself $97 million over the original 1995 estimate.

Although dominated by the retractable roof’s massive frame, T-Mobile Park’s 202-foot digital scoreboard behind the center-field fence is among the majors’ longest.

From the start, the Mariners publicly vowed to pay all cost overruns on T-Mobile Park, but cold reality hit when they received that portion of the final bill—$100 million. Performing a legal balk, the team parsed through the original agreement and insisted that the public, not it, was “obligated” to pay off the overages. The dispute centered on whether taxes funding the ballpark had a monetary ceiling relative to the budget (as the PFD argued) or to a 20-year life span, as the Mariners claimed. However valid or invalid, the Mariners’ perceptive about-face sent the public into a maddening howl, souring the celebratory mood as T-Mobile Park’s first game neared. Even Senator Slade Gorton didn’t appear willing to lend his usual backbone to the Mariners, stating that the team was “swimming upstream against a strong current” on the issue.

A Breath of Fresh Air.

On July 15, 1999, off-field controversies were tabled as Safeco Field—the ballpark’s original name—opened its gates, marking the first time a major league baseball team had moved outdoors from an indoor facility. Though the cool skies were not accompanied with any threatening elements, the roof was nonetheless closed for show during pregame festivities, the Seattle Symphony adding drama behind the center field fence with a playing of Also Sprach Zarathustra (or, to the common layman, the theme to 2001: A Space Odyssey). Senator Gorton, all too rightfully, threw out the first pitch. The roof reopened, 44,607 spectators settled in and witnessed the Mariners take a 2-1 lead into the ninth inning against the San Diego Padres—only to watch a troubled Seattle bullpen walk four batters and donate the Padres a handout 3-2 victory.

For fans of that night and every game since, the result on the field isn’t the only thing that matters at T-Mobile Park, as evidenced by the multitude of fans walking around and checking out the new digs.

On the way to their seats, most spectators pass through the ballpark’s semi-circular main entrance—entitled Home Plate Gate—and are instantly welcomed from above by a chandelier made of a thousand translucent bats suspended in a swirling motion. Though it has the look of a giant headhunter’s necklace, it represents a baseball player swinging through the motions like a Puget Sound wave. The “grand staircase” below, and the materials used to build it, is designed to reflect the experience of sailors being brought to shore.

Once up the stairs, you not only find yourself at the base of one of the widest concourses in all of baseball—up to 40 feet at some points—but also on top of a sizeable terrazzo compass borrowed from the Mariners team logo. Smoothly anchored within the concrete and measuring 27 feet in diameter, the compass causes spectators not so much to examine for any proverbial direction as to check out signatures of Seattle players from the ballpark’s inaugural game, etched in small circular stone capsules within it.

The Mariners’ Hall of Fame is just one part of the Baseball Museum of the Pacific Northwest, a casual, linear walk that starts near T-Mobile Park’s main entrance. It’s more than just about the Mariners, reaching back over a century into baseball history within the Northwest region.

Borrowing from Coors Field in Denver, one can walk the entire length of the concourse and always be able to see the action on the field. But there are artistic diversions along the way. Along the first base side on facing walls stand two sets of “quilts,” using discarded materials such as license plates, aluminum cans and wire to resemble logos of major league teams on one side, emblems of Seattle baseball teams of lore on the other. Further along, behind center field, a colorful triptych mural entitled “The Crowd” shows an assortment of fans and ballpark perishables mixed in with pop-up bubbles of famous ballplayers and familiar baseball postures.

Toward the left field bleachers, fans walking the concourse can step down and visit The ‘Pen, an outdoor lounge area open two and a half hours before gametime—a “hot happening event,” according to the Mariners. With its fire pit, voluminous selection of local beers and wine, and excellent open-air views of the field, The ‘Pen is T-Mobile Park’s pregame meeting place, the closest thing to a nightclub—and judging from the demographics, the vibe looks pretty sharp.

The Terrace, or second, level houses plusher dining with the Hit It Here Café, located behind the right field wall. There’s no discrimination to be found here; any ticket holder can dine, whether indoors or out. Advance reservations would be wise, however—especially if you want a great window seat.

Sushi chefs stand at the ready inside the Hit it Here Café’, located on the second level behind the right field wall.

Also on the Terrace Level are T-Mobile Park’s 60 luxury suites, all named after Hall of Fame players. The interiors reflect a more laid-back, fashionable Northwest décor, including island counters topped with dark green slate, furniture using various types of finished wood, and walls painted in khaki and plum. In 2007, nine of the suites along the right-field line were taken out and replaced by the All-Star Club, for those who don’t necessarily have the cash or the extended family to buy and fill up a suite. It’s still not entirely cheap, but when you add in the splendid buffet, plush seating and VIP parking, the value is hard to resist.

Further away from the action, the upper deck concourse on the ballpark’s west side allows fans to enjoy wondrous views of downtown Seattle, Elliott Bay, and the Olympic Mountains off in the distant west. A spectacular sunset can easily distract spectators from taking their seats for the first pitch on a warm summer evening.

The Left Field gate at T-Mobile Park slices between the main ballpark bowl and a brick building (at right), which houses the Mariners’ team offices.

Below this view and branching out of the ballpark bowl is the facility’s west wing, occupied on all but the first floor by the Mariners’ team offices. On the ground level, the Mariners Team Store features, among other items, rack after rack of every Mariners cap design ever conceived; next door, a Tully’s Coffee cafe initially answered the question, “What ballpark in Seattle wouldn’t be complete without a java stop?” (Perhaps the coffee boutique movement has simmered in Seattle; a bagel joint now resides where Tully’s once was.)

If the collection of dark green steel beams within T-Mobile Park’s interior doesn’t remind fans of the ballpark’s surroundings, then the trains will. No game goes by without at least one train passing by behind right field and, its blaring horns loudly making its presence felt—a sort of nostalgic variation on the jetliners that used to buzz New York’s Shea Stadium. The Mariners light-heartedly believe there’s some “cowboys in the engines” that ham it up to be heard by the crowd.

All Hail the Pitching Duels.

Besides the howling locomotives, fans at T-Mobile Park have discovered another new novelty: Low-scoring ballgames.

The Kingdome had played the final three months of its Mariners tenure in 1999 to an absurd statistical level, as if defiantly flaunting its reputation as a slugger’s haven before being abandoned. Mariner hitters batted .297 with a whopping 75 home runs—an average of nearly two a game—over those final 39 games at the Kingdome. That was nothing, however, compared to opponents who slammed Seattle pitching with a .324 average and seven runs per game. Yet, the Mariners managed to escape the Kingdome with a 20-19 record.

Seattle ace pitcher Felix Hernandez performs long tosses in front of fans assembled at The ‘Pen, a multi-atmosphere lounge behind the outfield fence that offers a wealth of food and drinks to create the ultimate pregame environment.

T-Mobile Park’s more spacious field distances, salty air and outdoor wind flow rescued the Mariners pitching staff, but bruised the egos of the team’s superstar sluggers who knew their candy-coated Kingdome numbers would be curbed. Ken Griffey Jr., Alex Rodriguez and Edgar Martinez complained that the power alleys were too deep, and instantly the buzz went out that the building erected to retain these perennial All-Stars was in danger of losing them.

Rumor became fact in short order. Griffey opted for Cincinnati after playing just three months at the new yard; Rodriguez followed a year later, unable to resist better hitting conditions and a blockbuster, 10-year, $252 million deal to play for the Texas Rangers.

Denials from both players that T-Mobile Park had anything to do with their exits were thinly veiled at best. Many teammates spoke up afterwards of Griffey’s long-term quest to break Hank Aaron’s career home run mark, that he wasn’t going to reach 756 playing half his games in Seattle. And Rodriguez, shortly before signing with the Rangers, went on his own web site to publicly lobby the Mariners to bring in the fences. They wouldn’t.

Those staying behind have prioritized winning over individual ambition. They’ve been rewarded. Though T-Mobile Park will likely not turn All-Star sluggers into hitless wonders, it has become the exception to the rule for new ballparks—one that favors the pitcher. That’s good news for the home team, because that typically means more innings for starters and fewer for a Mariners bullpen that was taxed beyond belief back in the Kingdome.

In their first three months at Safeco Field to close out the 1999 season, the Mariners yielded a respectable .249 batting average—a blissful far cry from their painful Kingdome numbers, and a figure that would be something of the norm going forward. Without Griffey, the 2000 Mariners would win 91 games and reach the postseason as a wild card; without Rodriguez and with the addition of Japanese hitting machine Ichiro Suzuki, the 2001 edition would turn heads everywhere within baseball with a stunning, record-setting 116-46 record. Both campaigns ended one stop shy of the World Series, as the Yankees trumped them twice at the ALCS. Still, Safeco Field became the place to be—evidenced by back-to-back seasons of 3.5 million turnstiles clicked in 2001-02.

Ultimately, the pitcher-friendly atmosphere began to sour upon the Mariners and their fans. Dwindling offense led to dwindling results that led to dwindling attendance. It proved that a ballpark by itself can only win half the battle. Talent would be responsible for the other half.

When both the Mariners and their opponents combined to hit a paltry .225 at Safeco in 2012—a year noted for two perfect games at the park, including the Mariners’ first ever via popular ace Felix Hernandez—the Seattle front office decided to bring in the fences from right-center all the way to the left-field foul pole, but most significantly in the left-center gap where up to 12 feet was shaved away. Early returns show a definite increase in home runs, but it goes both ways; where the Mariners benefit is where opponents do, too. Offense improved, but the Mariners wins and attendance remained flat. Better talent would have to take care of the latter two equations.

Fans buddy up to the bronze likeness of popular team broadcaster Dave Niehaus, who threw out the first pitch at T-Mobile Park’s first game and died in 2010 after 34 years in the Mariners’ booth. No other person would be immortalized in bronze at the ballpark until Ken Griffey Jr. in 2017.

SODO Mojo.

Baseball fans coming to T-Mobile Park find true magic in the open air south of downtown, or south of the dome as some believe “SODO” to mean—there’s not even a “dome” to be south of anymore, since the Kingdome was razed for all to see in March 2000. The ballpark thrives as a pleasant reminder of how far Seattle baseball has come, to say nothing of a once-neglected industrial corridor that has become alive with chic activity. At T-Mobile’s northwest gate, young fans eagerly climb about a nine-foot high bronze mitt with a hole in the middle to crawl through. The parents, tickets held in hand, let them have fun before going inside to watch the big boys play. Rain or shine, blue skies or gray, it no longer matters. Baseball is here to stay in Seattle, and T-Mobile Park is its ballplaying emerald.

The Ballparks: Kingdome It was built to last a thousand years but barely made it past the age of 20, a swirling, petrified cupcake bitten into by locals who initially loved it for firmly pinning Seattle on the pro sports map but quickly disliked once the new stadium smell wore off. The Kingdome and the National Pastime were not to be the match made in Northwest heaven, as a brand of arena baseball ensued with high fly balls ricocheting here, there and everywhere over a zipped-up chunk of fake turf.

The Ballparks: Kingdome It was built to last a thousand years but barely made it past the age of 20, a swirling, petrified cupcake bitten into by locals who initially loved it for firmly pinning Seattle on the pro sports map but quickly disliked once the new stadium smell wore off. The Kingdome and the National Pastime were not to be the match made in Northwest heaven, as a brand of arena baseball ensued with high fly balls ricocheting here, there and everywhere over a zipped-up chunk of fake turf.

Seattle Mariners Team History A decade-by-decade history of the Mariners, the ballparks they’ve played in, and the four people who are on the franchise’s Mount Rushmore.