THE YEARLY READER

2024: Best of Sho

The incomparable Shohei Ohtani joins the Los Angeles Dodgers, injecting strength and promise into their elusive championship ambitions.

Shohei Ohtani gets congrats from both teammates and fans after hitting his 50th home run of the season on September 19 at Miami. The round-tripper made the first-year Los Angeles Dodger the first major leaguer to collect 50 homers and stolen bases in the same season. (Associated Press)

For much of the previous decade, the Los Angeles Dodgers were beginning to understand how their ancestors in Brooklyn felt. Visions of dynasty, fueled by All-Star rosters and bankrolled by a seemingly unlimited supply of ownership money, led to unlimited expectations at the start of each year. During regular season play, the Dodgers met those expectations, winning the National League’s Western Division 10 times in 11 years; the one time they finished second, in 2021, they won 106 games. In four of those 11 seasons, they produced the league’s best record.

October, however, would repeatedly cast an early autumn chill upon the Dodgers’ championship hopes. True, they won the 2020 World Series, but that triumph carried the stigma of playing in a year remembered for a heavily shortened schedule, empty ballparks, and rosters decimated by the COVID-19 pandemic. Otherwise, the Dodgers suffered five first-round playoff exits, three defeats in the NL Championship Series, and two setbacks in the World Series. Anyone still around who experienced those unhappy third acts back at Ebbets Field could relate.

Star hitters, abundant pitching talent, and a trove of supporting assets who could play any position were continuously not enough for the Dodgers to get over the top. They needed that extra push, that clinching burst of winning energy. A superstar of superstars.

On December 9, 2023, they found one.

Down the freeway in Anaheim, Shohei Ohtani entered free agency after six years of remarkable output with the Angels. It could be argued that the Japanese native was a six-tool player; he could hit for average and power, run like the wind seemingly without effort, excelled defensively at fielding and throwing—and he could pitch. On top of all of that, Ohtani was highly likeable among teammates and usually quiet, in large part because he had yet to master the English language.

Not since Babe Ruth had baseball seen anyone who could excel both at the plate and on the mound, making Ohtani a once-in-a-century phenomenon. Tired of being stuck on losing squads with the Angels, he was finally free to offer himself to the highest bidder.

It was widely anticipated that Ohtani would easily eclipse the $360 million contract paid to slugger Aaron Judge by the New York Yankees a year earlier. Most pundits were envisioning somewhere in the neighborhood of $500 million for the two-way talent, even as he was in the early stages of recovery from his second Tommy John surgery—thus negating his availability as pitcher and fielder for the short term.

The half-billion estimate would be scoffed at by the Dodgers, reaching into their pockets for a few hundred million more bucks to satisfy Ohtani into donning Dodger Blue.

Ohtani’s record-shattering $700 million deal with Los Angeles would be all the more eye-opening once it was learned that he would defer all but $2 million of his annual salary in each of the 10 years he’d be contracted for. Past wages from the Angels and a gluttony of endorsements deals would keep him financially comfortable before the deferrals kicked in.

The play-now, pay-later approach with Ohtani allowed the Dodgers to remain aggressive on the hot stove circuit with the attitude of a drunken sailor, because they could afford to. They reached out across the Pacific to snag another Japanese star in ace Yoshinobu Yamamoto for 12 years and $325 million—the largest-ever payout given to any pitcher; traded for top-tier but injury-prone pitcher Tyler Glasnow from Tampa Bay, rewarding him in advance with a five-year extension worth $136 million; and appended All-Star catcher Will Smith for 10-years and $140 million. By the time the accountant was done widening the Excel columns with these and other, relatively smaller deals, the Dodgers had committed close to $1.5 billion in guaranteed payments during the 2023-24 offseason.

As important as the Dodgers’ other moves were, they were merely ancillary in the minds of Los Angeles fans compared to Ohtani’s boundless potential and megastar persona they eagerly salivated over.

They would not be disappointed.

The Ohtani Feel-Good Express nearly derailed before it left the station while the Dodgers were engaged in an early regular-season kickoff series in South Korea against the San Diego Padres. Ohtani’s long-time interpreter Ippei Mizuhara, who claimed he and Ohtani were so joined at the hip that they spent more time together than with their spouses, confessed to ESPN that he had used Ohtani’s bank account to feed a gambling habit, leaving him millions in the hole with an illegal sports bookie in California—and that Ohtani paid off the debts. Oddly, the interview was set up—then later denounced—by Ohtani’s reps, leading everyone from seasoned baseball reporters to social media keyboard junkies to theorize whether Ohtani was more nefariously involved, perhaps to use Mizuhara as a fall guy to cover his own gambling habits. MLB braced for the potential of another significant scandal involving a superstar, as it had in the past with Joe Jackson, Pete Rose, and numerous steroid-tainted headliners.

The truth would slowly reveal itself. Ohtani, it turns out, was uninvolved and unaware of Mizuhara’s addiction that included an average of 25 bets per day and a total net loss of $40 million—forcing him to divert $17 million from Ohtani’s personal coffers. Federal investigators pored through the evidence and eventually cleared Ohtani, with Mizuhara left looking at jail time and massive debt reimbursement—and Ohtani looking for a new interpreter.

BTW: As Mizuhara’s debts intensified—ultimately averaging $2,500 per bet—he texted to his bookie: “I’m terrible at this sport betting thing huh? Lol…”

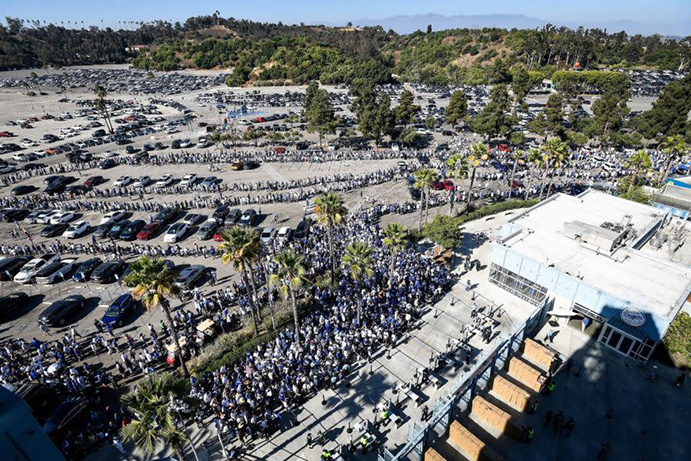

A miles-long line of Dodger fans waited up to 10 hours to ensure they’d receive a bobblehead of Shohei Ohtani and his dog Decoy on August 28. (Los Angeles Dodgers)

In the clear, Ohtani regained his focus on baseball; with a demeanor as chill as his, he probably never lost it. Anchoring a Dodgers lineup further spiced with All-Stars Mookie Betts and Freddie Freeman, Ohtani quickly kicked into gear and only sped up as the season moved forward, accelerating a push toward uncharted statistical territory with his power racking up the home runs and legs racking up the stolen bases. Not even a healing elbow, keeping him from pitching or throwing, could slow down his accumulation from the designated hitter’s spot.

With two full months to play in the regular season, Ohtani became the third player in Dodgers history to record a 30-30 season—30 homers, 30 steals. Just 20 days later, he made it 40-40, something previously accomplished by only five major leaguers. Ohtani now had 33 games left to attain a previously unbreakable barrier of 50-50.

He only needed 24 games.

On September 19 at Miami, Ohtani began the day with 48 home runs and 49 steals; three homers, two doubles, a single, 10 RBIs and two steals later, he ended it at 51-51, as the Dodgers routed the Marlins, 20-7. Legend had cemented itself; some considered Ohtani’s single-game performance as among the greatest—if not the greatest—in baseball history.

BTW: Ohtani’s 50th home run set a Dodgers season record; his 10 RBIs were the most ever recorded by an MLB leadoff hitter, as Ohtani had taken over the role after Mookie Betts fractured his hand in June—maintaining the spot even after Betts’ return.

The Perils of Possession

Trying to grab a piece of Shohei Ohtani home run history was fraught with risk. Ask Ambar Roman, who caught Ohtani’s first Dodger home run on April 3 at Los Angeles; ballpark security surrounded and separated her from her husband, dictating the swag (two caps signed by Ohtani) they would give for the ball, and telling her that the Dodgers would not authenticate the ball if she held tried to sell it. Once the public got wind of the strong-armed tactics, the Dodgers—shifting into P.R. damage control—gifted Roman with a wealth of dispensation. All of that paled in comparison to the controversy surrounding ownership of the home run ball that made Ohtani baseball’s first-ever 50-50 (homers/steals) man. Sailed into the bleachers at Miami’s loanDepot park on September 19, the ball was wrestled over for a good half-minute before Christian Zacek emerged with the pricey memento. But Zacek was sued by not one but two fans, each claiming they had initial possession of the ball. While the courts figured out who was the rightful owner, the ball sold online for $4.392 million—for the moment, the largest-ever amount paid for a baseball.

His record achievement behind him, Ohtani did not rest. In the season’s final week-plus, he added three more homers and eight more steals, bringing his year’s total to, respectively, 54 and 59. Additionally, he led the majors with 134 runs and became the first major leaguer in 23 years to accrue over 400 total bases. Only the Padres’ Luis Arraez, batting .314, stood in the way of Ohtani winning the NL’s first triple crown of batting since 1937, as he finished a close second with a .310 mark.

To say that Ohtani won over Dodgers fans was a massive understatement. Ohtani Dodger jerseys vanished from souvenir shops as quickly as they were racked up. Two Ohtani bobblehead days at Dodger Stadium brought out early-bird fans waiting hours in a seemingly endless line, hoping to be one of 40,000 to receive the collectable. Then there was the near-obsessive attention given to Ohtani’s dog Decoy, a Kooikerhondje who became a social media hit, was given an honorary passport by the U.S., and participated in a ceremonial first pitch—running from the mound to home, ball in mouth, with Ohtani awaiting behind the plate.

As anticipated, Ohtani’s presence on an already strong Los Angeles roster resulted in another NL West title, never once trailing in the standings. The Padres, continuing to aggressively retool and improve even in the wake of owner Peter Seidler’s recent passing, admirably managed to draw within a couple games of the Dodgers at several late points of the season, but never caught up.

That the Dodgers remained at the top of the division was impressive considering that their pitching staff—especially the rotation—resembled a China shop after the bull had stampeded through. Seventeen different pitchers started a game for the Dodgers; only two of them threw more than 100 innings. Yoshinobu Yamamoto, the team’s other big Japanese-born acquisition, missed three months to a rotator cuff strain. Veteran ace Clayton Kershaw missed the first four months recovering from offseason shoulder surgery—then after seven starts was shut down with a bone spur in his big toe. At least five other starters—including Walker Buehler and Tony Gonsolin—missed all or parts of the year recuperating from or undergoing Tommy John surgery.

Winning the West was, as always, the easy part for the Dodgers. Now came October and the Moment of Truth; could the Dodgers, with Ohtani now on board, finally find more resilience in the postseason and disrupt the decade-long pattern of lower-seeded teams snatching the upset?

The path toward a ring would not be easy. In a feisty NL Division Series, the Padres—who had temporarily replaced the San Francisco Giants as the Dodgers’ chief archrival—won two of the first three contests amid mind games and back-and-forth barking between the two teams. San Diego left fielder Jurickson Profar was at the center of this psychological warfare, teasing the Dodger Stadium crowd over whether he had stolen a home run from Mookie Betts in Game Two (he did) and later verbally clashing with Dodgers catcher Will Smith, who earlier in the year called the first-time All-Star “irrelevant.” The Dodgers, feeling a dark déjà vu in light of early playoff exits to NL West teams the previous two years (including the Padres in 2022), faced the task of having to win the final two games to advance; that they did, as stout pitching—mostly from the bullpen—carried Los Angeles to 8-0 and 2-0 wins to silence Profar and the Padres.

BTW: After everyone thought Profar hadn’t stolen Betts’ deep fly in Game Two, Betts in Game Three sent another long ball to the top of Petco Park’s left-field fence that everyone thought Profar had caught—even Betts, who began to turn back to the dugout between first and second before umpires, realizing Profar came up empty-gloved, redirected him to complete his home run trot.

The Dodgers’ NLCS opponent would provide a more stifling challenge, though few wouldn’t have believed it some five months earlier.

On May 29, the New York Mets were a lost team, one that threatened to unravel in a 10-3 loss to the Dodgers. That night was lowlighted by a meltdown from reliever Jorge Lopez—who responded to an ejection by untucking his shirt, chucking his glove into the stands, and then redirecting his vitriol on the Mets in a postgame presser, calling them “the worst team in probably the whole f**king MLB.” Lopez wasn’t far off with his assessment; at that point, only four teams had worse records than the Mets’ 22-33 ledger.

From that low point, the Mets rebounded like a rubber ball, posting the majors’ best record—better even than the Dodgers—from May 30 through the remainder of the regular season; though they were unable to catch the first-place Philadelphia Phillies for the NL East title, they overtook them in an NLDS matchup, three games to one. Boisterous Mets fans gave credit for the team’s bounce-back to Grimace, the purple McDonald’s blob whose ceremonial first pitch at Citi Field in early June “ignited” the Mets; but the real boost came from a rotation anchored by reclamation projects (Luis Severino, Sean Manaea, Jose Quintana) that bent but rarely broke, and most especially from shortstop Francisco Lindor—whose awful start mirrored that of the Mets, before equally surging with one clutch moment after another, finishing the year with 33 homers, 91 RBIs, 39 doubles, 107 runs, and 29 steals.

Lindor’s late-season performance was viewed as so valuable, some even suggested that he, not Shohei Ohtani, be given the NL MVP. But in the NLCS, the Dodgers’ star reaffirmed his standing as the overwhelming choice for the award. Against the Mets, Ohtani reached base 17 times—nine by walk, as New York pitchers quickly grew wary of giving him anything good to hit—and he belted home runs in the third and fourth games, crucial victories that propelled the Dodgers to a 3-1 lead in a series they’d win in six.

With one New York team behind them, the Dodgers next faced another at the World Series: A traditional foe in the New York Yankees.

Like the Dodgers, the Yankees had been experiencing their own drought of glory with an ongoing streak of 15 years without a pennant—matching their longest such dry spell during the franchise’s century-long reign as a baseball power. They had the game’s premier slugger in Aaron Judge and, for 2024, they had the omnipotent Juan Soto, playing for his third team in as many years after being dealt to New York by the Padres. (He’d make it four teams in four years after the season, topping Ohtani with a $765 million pact for the cross-town Mets.) What they didn’t have was much of anything else on offense—a collection of players beyond Judge and Soto producing a lackluster .680 OPS—and little pitching to initially brag about beyond reigning AL Cy Young Award winner Gerrit Cole, himself unavailable until June 19 after a Spring Training elbow injury.

The Yankees would roller-coaster it through the campaign, bursting out to a 50-22 start before losing 23 of their next 33 games, righting themselves down the stretch to the American League’s best record at 94-68—outpacing by three games a strong Baltimore unit under promising new ownership after three decades of rule by the Angelos family. Judge threatened his own AL season home run record from two years earlier—hammering #50 on August 25—before being held homerless over a career-long 16-game stretch. He nevertheless finished the season as, like Ohtani in the NL, the clear favorite for the AL MVP batting .322 with 58 homers and MLB highs in RBIs (144), walks (133), on-base percentage (.458), slugging (.701), and therefore OPS (1.159). Soto, batting in front of Judge all season long, benefitted with a personal-best 41 homers, 109 RBIs, league-leading 128 runs scored and, even with Judge lurking on the on-deck circle, 129 walks.

On the mound, the Yankees got pleasantly surprising returns from their rotation beyond Cole’s expected yield returning from the injured list. Carlos Rodon, lost the year before amid multiple injuries, led the team with 16 wins. Marcus Stroman, wearing pinstripes for the first time, quietly chipped in with a 10-9 mark. And rookie Luis Gil, sidelined by Tommy John surgery the previous two seasons, made for an excellent first impression by furnishing a 15-7 record, 3.50 ERA and opposing .189 batting average—leading to AL Rookie of the Year honors.

BTW: Adding extra spark—and vibe—for the Yankees down the stretch was Jazz Chisholm, Jr. freed from the 100-loss-bound Miami Marlins in late July; in 46 games for the Yankees, Chisholm batted .273 with 11 homers and 18 steals.

In the postseason, the Yankees stiff-armed away the Kansas City Royals and Cleveland Guardians—two revitalized teams from a strengthened AL Central. Giancarlo Stanton, dimmed out of a Yankee spotlight afforded all year to Judge and Soto, beamed bright with six home runs—including four for each of his hits against the Guardians in a five-game ALCS triumph.

The Yankees’ Aaron Judge (left) and Juan Soto celebrate one of the 99 home runs hit between the two; it would be the most bashed by a major league duo since 2002. Soto’s 2024 season would be his first—and last—with the Yankees; he would sign an 11-year, $765 million contract with the New York Mets following the season that would surpass the total payout given to Shohei Ohtani. (Associated Press)

The ensuing World Series was viewed as a clash of titans on two fronts: the 12th Fall Classic between formidable, longstanding rivals in the Dodgers and Yankees and, on a more individual level, the main event between Ohtani and Judge, two Hall-of-Fame luminaries at the peak of their careers.

One mano a mano would turn out one-sided; the other would become a dud.

The Dodgers won the first three games, threatening to turn the series into a rout. But they would have to do it with a seriously handicapped Ohtani; in Game Two, he suffered a partially separated left shoulder—in medical textbook terms, a subluxation—during an unsuccessful stolen base attempt. Word on the beat was that he was done for the series, but Ohtani defied the prognosis and carried on with his DH duties—albeit carefully, holding his left arm close to his chest whenever forced to run, as if wearing an invisible sling. He managed just a single in 10 at-bats after the injury, but that he avoided being sidelined was in itself a mild miracle.

With Ohtani far from 100%, the Dodgers picked up the slack. First baseman Freddie Freeman, himself hobbled with a sprained ankle and broken rib cartilage, belted a grand slam in the 10th inning to wrap up a 6-3 Game One victory, then went deep in each of the next three games—giving him a World Series-record six straight games (dating back to his time with the Atlanta Braves in 2021), with a home run. Walker Buehler, entering the series with an 0-6 record and 6.46 ERA over his past 15 starts, pitched five shutout innings in a 4-2 Game Three win, then made a rare appearance as a reliever in the Game Five clincher, pitching a 1-2-3 ninth to close out the Yankees.

Ohtani, Freeman, and Buehler aside, the Yankees essentially beat themselves in that fateful fifth game. Building up a quick 5-0 lead behind Judge—jumping back to life after a 7-for-46 postseason to date with a first-inning, two-run homer—New York coughed it all up in the fifth via numerous errors both mental and physical. Judge dropped a fly ball. Shortstop Anthony Volpe made an ill-advised—and errant—throw to third on an attempted force play. Ace Gerrit Cole failed to cover first on a Mookie Betts grounder to first baseman Anthony Rizzo, who had to eat the ball. Bags full with two outs, the next three Dodgers hitters reached safely to cap a game-tying five-run rally, with each tally unearned. A pair of sacrifice flies in the eighth put the Dodgers ahead to stay.

BTW: Underscoring the fact that Ohtani was just as idolized in his native land as in Los Angeles, the World Series attracted more viewers in Japan than America.

Back in Los Angeles, the Dodgers celebrated their first full-season World Series triumph in 36 years before a crowd of over 40,000 at Dodger Stadium. Of course, Shohei Ohtani was accompanied by his dog Decoy. Eventually, Ohtani was given the microphone, speaking for 20 seconds and thanking the fans—in English, as Ippei Mizuhara was long gone and too busy trying to remain a free man.

The Dodgers clearly got their money’s worth—whether paid for now or later, starting in 2034—and Ohtani received the spoils. He was awarded with a third career MVP—unanimously, like the previous two honors—among many other year-end accolades, and had become the game’s most popular player. Along with his team, Ohtani had conquered.

And he still had yet to pitch for the Dodgers.

Back to 2023: Get Them Home by Ten New rules intended to speed up the game and increase offense lead to one of Baseball’s most transformative seasons—and ends with the wild-card Texas Rangers conquering the first world title in their 63-year history.

Back to 2023: Get Them Home by Ten New rules intended to speed up the game and increase offense lead to one of Baseball’s most transformative seasons—and ends with the wild-card Texas Rangers conquering the first world title in their 63-year history.

2024 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 2024 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

2024 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 2024 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

The 2020s: The Turbulent Twenties Intended changes and unexpected disruption mark a time when Baseball attempts to appeal to a bigger audience, risking the loyalty of its most ardent followers. But an impressive influx of talented young players hopes to rescue the era and keep everyone happy.

The 2020s: The Turbulent Twenties Intended changes and unexpected disruption mark a time when Baseball attempts to appeal to a bigger audience, risking the loyalty of its most ardent followers. But an impressive influx of talented young players hopes to rescue the era and keep everyone happy.