THE YEARLY READER

1915: The Great Connie Mack Fire Sale

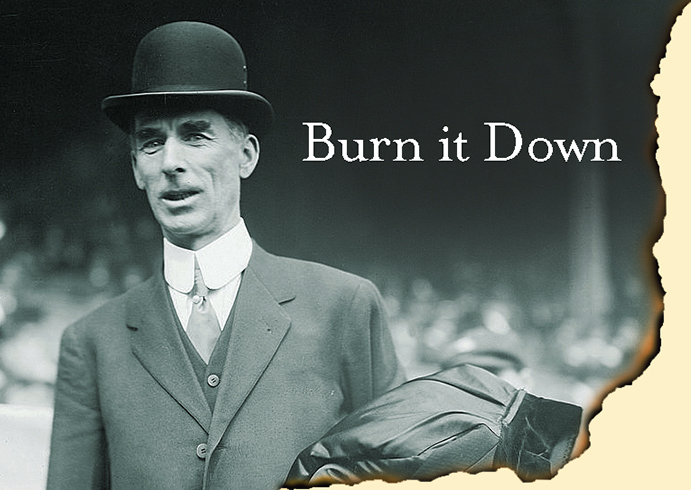

Sensing bad vibes and bad finances, Philadelphia A’s manager Connie Mack tears apart his first dynasty.

Having won four of the last five American League pennants, Philadelphia A’s front man Connie Mack sees too much red ink from rising player salaries and dumps his star talent, diving what’s left of a once-invincible squad into an unprecedented freefall.

As the Federal League began its second campaign in 1915, more than a few wondered whether it could play out the year.

Though the FL had staged a fine first impression on the baseball public, the money put forward to spearhead its effort was fast evaporating. The only solution it could think of was to sue major league baseball for antitrust violations. Hearing the case in Chicago would be a famed, crusty trustbuster who doubled as a devout baseball fan: Kenesaw Mountain Landis.

While the FL was quickly making a victim of itself in saturating the baseball market, it was also making an impact on the two established major leagues as well.

Nobody felt that impact worse than Connie Mack and his Philadelphia Athletics.

As the American League entered its 15th season, Mack had emerged as its goodwill ambassador. His gentile personality was matched by his ability to bring constant success to his franchise. Mack remained as the league’s only active charter manager, and in his 14 years with the A’s, he produced six AL pennants with three World Series triumphs—all achieved over the previous five years, courtesy of the league’s most powerful dynasty to date.

But even as the A’s ran away with another pennant in 1914, attendance shrunk to nearly half the previous year’s total, the Shibe Park faithful perhaps more spoiled over their team’s monotony of dominance.

While the Feds had little to do with the A’s decreased gate—they provided no direct competition in Philadelphia—they were more likely to be blamed for the state of mind in Mack’s clubhouse. Baseball’s best grouping of talent had begun to argue with one another over who would jump to the Feds and who would remain loyal to the Tall Tactician.

BTW: A deep national recession may have contributed to a 40% drop in ticket sales for the A’s during the 1914 season.

But after the A’s sleepwalking performance against the Miracle Braves in the 1914 World Series, the only loyalty Mack could entrust was to his franchise’s bottom line. He knew his vast supply of talented players would slip away to the Feds if he didn’t pay them what they thought they were worth. Problem was, the A’s were losing lots of money—with not much left.

Mack knew that, one way or the other, his dynasty would get dismantled. So he decided to do it himself, on his own terms.

Wasting little time after the Series loss to Boston, Mack set an unmistakable tone for what was to follow. In one day, he released his three top veteran pitchers—Eddie Plank, Chief Bender and Jack Coombs—who between them had won 596 games for Mack, nearly half of the A’s all-time total to date. All three pitchers cleared waivers and Mack lost any chance to get something in return. Free agents all, Plank and Bender migrated to the Federal League, Coombs to Brooklyn.

Shortly thereafter, Mack had to send Eddie Collins, his best offensive weapon, to Chicago after Collins threatened to jump to the Feds. White Sox owner Charles Comiskey paid Mack $50,000 to acquire Collins and assume his multi-year contract at $15,000 a season.

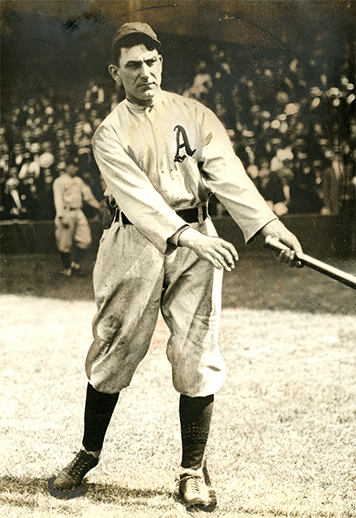

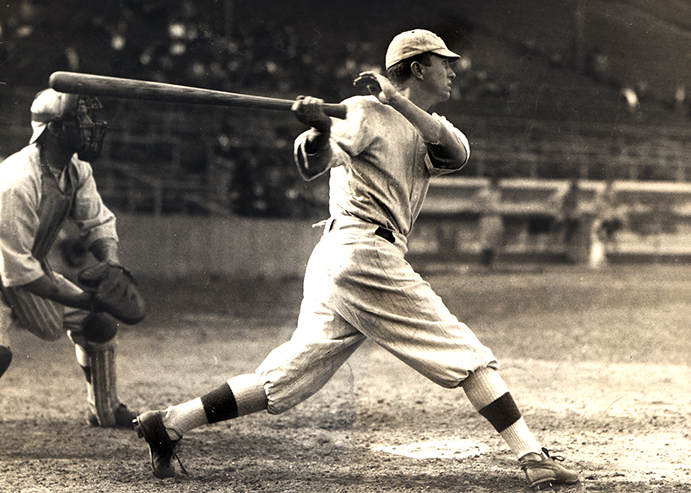

While most star players were exiting out of Philadelphia, future Hall of Famer Nap Lajoie came back to the A’s where he began his American League career in 1901. But at age 39, he had almost nothing left. (the Rucker Archive)

Home Run Baker, the team’s perennial deadball slugger also under a multi-year contract, wanted to stay with the A’s, but also wanted renegotiation. Mack wouldn’t budge, and neither would Baker, whose ensuing holdout would last through all of 1915.

Mack made one newsworthy acquisition during the offseason, bringing in Nap Lajoie from Cleveland. But at 39, Lajoie was no longer the superstar of lore, sending a clue that Mack’s purchase was a skeletal gesture to the fans.

If what was left of the A’s was to be underwhelming to their opponents, it wasn’t noticed on Opening Day. Starting pitcher Herb Pennock threw a one-hit shutout against the Boston Red Sox, with Harry Hooper breaking up a no-hit bid with two outs in the ninth.

A month later, Mack punished Pennock for being too good; he was placed on waivers. Having seen him up close and personal, the Red Sox gladly picked up Pennock, who resumed his trek towards the Hall of Fame.

Things went immediately downhill after Opening Day. Lajoie committed five errors in a game one week later. The A’s headed straight for last place, and when it seemed they had hit rock bottom, they fell even deeper.

Four of the A’s top pitchers, from left to right: Herb Pennock, Weldon Wyckoff, Bullet Joe Bush and Bob Shawkey. In 1914, they combined to go 54-32 with a 2.90 ERA; a year later, the same group deteriorated to 24-48 and 3.91. Pennock and Shawkey would be traded before the year was done. (Library of Congress)

The talent of the young pitching staff evaporated. Rube Bressler, who in 1914 won 10 of 14 decisions with a stellar 1.77 earned run average, crashed to 4-17 and a 5.20 ERA in 1915. Bullet Joe Bush, a 17-12 hurler the year before, dropped to 5-15. Weldon Wyckoff led the A’s with 10 wins. He lost 22.

In one game Mack threw Bruno Haas at the opposition. Haas went the distance, but it was an exercise in torture; losing 15-7, he gave up 11 hits, a major league-record 16 walks, and threw three wild pitches.

BTW: Haas reinvented himself as a star minor league hitter with the St. Paul Saints during the 1920s.

As the team descended through the season, Mack continued to deal away his players for cash, though by now those who got traded we’re probably happy to go. Pitcher Bob Shawkey was sold to the New York Yankees; outfielder Eddie Murphy, to the White Sox; and shortstop Jack Berry, to the Red Sox. Berry’s departure left behind only Stuffy McInnis from the famed “$100,000 Infield,” a group of talent—if not a dollar figure—Mack could no longer afford to maintain.

By season’s end, the A’s were a laughable imitation of their former greatness. They finished at 43-109, a staggering 56-game turnaround from the year before. As their record plummeted, so did attendance. The average crowd at Shibe Park fell below 2,000.

Mack, to his credit, gave it all he could, as evidenced by a then-record 56 players he tried out in uniform during the season. He waxed philosophical when it was over, making the understatement of his career: “You can’t win ’em all.”

Unbelievably, it would get even worse before it got better for the Athletics. And it wouldn’t get better for a long time.

Freefall from Grace

By plummeting 56 games from their 1914 record, the A’s set the major league mark for the worst one-year performance drop. Below is the list of the five such steepest declines.

For the second straight year, Philadelphia and Boston would be represented in the World Series. But it would be the “other” teams—the Phillies and the Red Sox—vying for the title.

For the Phillies, it was their first National League pennant in their 33-year existence. Stuck for a decade around the .500 level, the Phillies broke to the top under rookie manager Pat Moran—but in getting there, they had to hold off another miracle attempt by the Boston Braves to claim the NL flag. As with 1914, the Braves went on a run after getting stuck in last place in July—but this time, the magic fell short. Boston could only extend as far as second place, finishing eight games back.

BTW: What the Braves lacked in 1915: Their clutch game and a decent batting average (the NL’s worst at .240).

Two top players who enjoyed the year of their lives boosted the Phillies. Pete Alexander had perhaps the finest season of his Hall-of-Fame career, leading the NL with 31 wins (against just 10 losses), a 1.22 ERA and an exhausting 376 innings pitched; opponents hit just .191 against him. Offensively, the Phillies were shouldered by slugger Gavvy Cravath, whose 24 home runs nearly doubled the runner-up total. It would be the most homers hit in the 20th Century before Babe Ruth emerged as an everyday hitter.

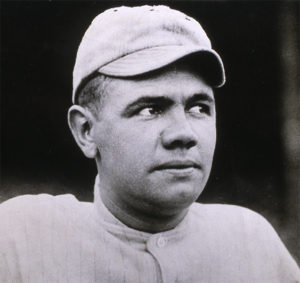

In his first full year in the majors, Babe Ruth excelled on the mound for the Red Sox with an 18-8 record and 2.44 ERA; with a bat, Ruth’s four home runs—in just 92 at-bats—led the Red Sox. (The Rucker Archive)

In Boston, it was Ruth who helped propel the Red Sox back to the World Series—mostly by pitching. The 20-year-old lefty won 18 of 26 decisions and was part of an impressively youthful five-man rotation. Ruth was also beginning to raise a few eyebrows at the plate; despite batting just 92 times during the year, Ruth’s four home runs were more than anyone else—regulars included—on the Red Sox. His .315 batting average was surpassed on the roster only by the great Tris Speaker.

The Red Sox survived a close and highly competitive pennant race with the Detroit Tigers to take the AL flag. Both teams had reached the 100-win mark, but the Red Sox had an extra win—and four less losses—to pull away by 2.5 games. Crucial was head-to-head competition between the two teams, of which the Red Sox won 14 of 22. Detroit fell short in spite of another batting title for Ty Cobb, who spiced the achievement with 96 stolen bases—a record that would stand for 47 years.

Both the Red Sox and the Phillies did what they could to bring in extra customers for the World Series. Those adjustments would first handicap, then backfire upon, the Phillies.

For the first two games at Philadelphia, owner William Baker installed 400 additional seats in right-center field to help ante up more cash for his coffers. He also did it to make Baker Bowl’s relatively small dimensions even cozier for slugger Gavvy Cravath against a Red Sox lineup that had shown no longball muscle all year. But Cravath was neutralized by stellar Boston pitching, and the Phillies were lucky to split the first two games thanks to Alexander’s solid Game One outing.

Life Before Ruth

In an era where 10 home runs in a season qualified a player’s reputation as that of a power slugger, Gavvy Cravath’s total of 24 in 1915 must have been considered quite a blockbuster. Cravath’s output was, in fact, the most by a player during the deadball era, before Babe Ruth began completely rewriting the recordbook in 1919.

A year after the Sox had loaned Fenway Park to the Braves during their World Series drive, the defending champs—having since built Braves Field—returned the favor and allowed the Sox to play at their new ballpark for the Series. Strategically, as well as economically, the decision was a no-brainer; Braves Field sat nearly 10,000 more spectators, and its immensely spacious outfield—which included a 550-foot distance from home plate to just right-of-center, and 400 feet down the lines—would hurt Cravath’s chances of driving one out.

Behind more outstanding pitching by Dutch Leonard and Ernie Shore, the Red Sox won both games at Braves Field by 2-1 scores to take a 3-1 Series lead back to Baker Bowl.

In a seesaw Game Five, the Red Sox became the ironic benefactors of William Baker’s greed. Outfielder Harry Hooper erased an early 2-1 Phillies lead by bouncing a line drive into the temporary bleachers behind right-center field—decreed, according to the ground rules, as a home run. After the Phillies reclaimed the lead at 4-2, the Sox tied it up in the eighth inning on a two-run homer—the legitimate, over-the-fence-on-the-fly kind—by Duffy Lewis.

During the 1915 regular season, Boston’s Harry Hooper hit two home runs. He equaled that total in the fifth and decisive game of the World Series against the Phillies at Philadelphia. (The Rucker Archive)

But in the ninth, Hooper again foiled Baker’s best-laid plans by drilling another bouncer into the same extra seating in right-center. The second of Hooper’s hoping homers matched his entire regular season total, and rewarded the Red Sox with a lead they would keep to help capture their third World Series title.

Only three Red Sox pitchers—Leonard, Shore and Rube Foster—were needed in Boston’s five-game triumph. Babe Ruth sat on the bench, appearing only once in the Series as an unsuccessful pinch-hitter. More frustrated was Gavvy Cravath, who at least had the chance to contribute. Handcuffed throughout, he managed only two hits in 16 at-bats.

Before the season closed down, Kenesaw Mountain Landis had closed his book on the antitrust lawsuit brought on by the Federal League—telling both parties to settle it amongst themselves. It neutered the Feds’ ability to sue for peace and forced them to negotiate, dooming any hope for survival.

Just before Christmas, the three leagues reached agreement. Fed owners in Chicago and St. Louis were allowed to purchase, respectively, the Chicago Cubs and the St. Louis Browns and bring aboard their players. Other Fed franchises got healthy doses of severance pay. All Fed players became free agents, and the league officially declared itself defunct after just two seasons.

Feeling they got the very short end of the settlement stick, owners for the Feds’ Baltimore Terrapins went back to court to keep the antitrust suit alive. Their long and winding road would lead to the Supreme Court seven years later, where they met resounding defeat—and witnessed the creation of a little something for baseball called the antitrust exemption.

Forward to 1916: A Test of Robins Brooklyn manager Wilbert Robinson takes on former pal and current foe John McGraw for the National League pennant.

Forward to 1916: A Test of Robins Brooklyn manager Wilbert Robinson takes on former pal and current foe John McGraw for the National League pennant.

Back to 1914: The Miracle Braves Cellar-bound in July, the usually hapless Boston Braves perform one of the game’s greatest turnarounds.

Back to 1914: The Miracle Braves Cellar-bound in July, the usually hapless Boston Braves perform one of the game’s greatest turnarounds.

1915 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1915 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

1915 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1915 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

The 1910s: The Feds, the Fight and the Fix The majors suffer growing pains as they deal with a fledgling third league, increased scandal and gambling problems, and a brief interruption from the Great War.

The 1910s: The Feds, the Fight and the Fix The majors suffer growing pains as they deal with a fledgling third league, increased scandal and gambling problems, and a brief interruption from the Great War.