THE YEARLY READER

1922: Yankees Go Home

The Giants sweep the Yankees for its second straight Series title, while serving eviction notices to their co-tenants at the Polo Grounds.

(Library of Congress)

Through the first two decades of the 20th Century, the New York Giants owned New York City.

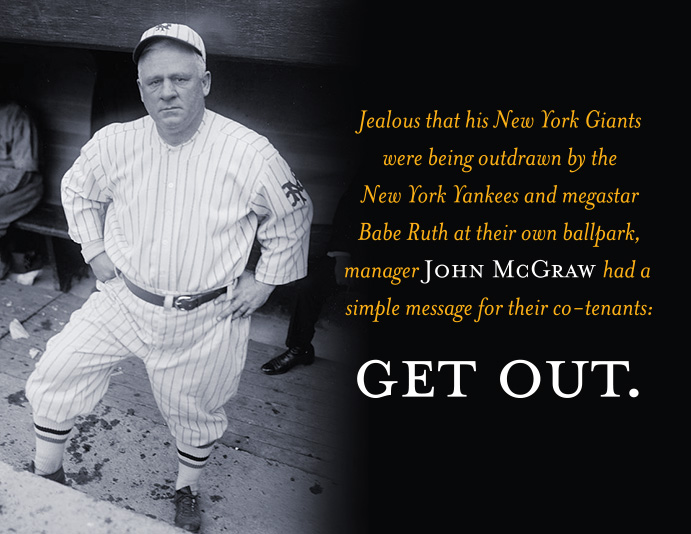

There were no comparisons; the toast of the Big Town, the Giants frequently outdrew the combined attendance of their two poor cousins, the Brooklyn Robins and the New York Yankees. Manager John McGraw, the fiery heart and soul of the Giants, reveled in his role as king of the New York baseball world.

But in 1920, Babe Ruth came to New York City, saw it, conquered it.

Suddenly, the Giants not only became the number two team in town, but number two in their own ballpark, which they shared with the Yankees. The Giants still played winning baseball, yet they lacked the bravado of Ruth and his 50-plus home runs. The tempestuous McGraw shook his head in angry disbelief as fans—over a million of them, a major league first—flocked to see the crowd-pleasing Ruth and his Yankees.

McGraw’s jealous reaction to the Yankees was predictably swift and venomous: Get out.

When the Polo Grounds went up in flames in 1911, the then-New York Highlanders offered the homeless Giants use of their venue, shoddy Hilltop Park. Responding in kind, the Giants allowed the re-christened Yankees to leave Hilltop in 1913 and pay rent at a rebuilt, steel-and-concrete version of the Polo Grounds. What was thought to be a one-year deal became an indefinite stay, one that became very strained once Ruth arrived and started packing ’em in for the Yankees.

Fortunately for the Yankees and their owners—the “Two Colonels,” Jacob Ruppert and Tillinghast Huston—they had money. Initially wanting to stay at the Polo Grounds, they offered to buy half interest in it, but the Giants ignored them. After a fruitless scouring of potential sites in Manhattan, the Yankees decided on a different locale for a ballpark of their own—practically next door to the Polo Grounds, right across the Harlem River.

The colonels paid $600,000 to acquire a former lumber yard some 10 acres in size from William Waldorf Astor. Their goal was to build the biggest baseball palace yet—a gigantic, three-tiered stadium that would house over 70,000 spectators, a potential crowd figure no other baseball team had yet approached. It would be named, simply if not aptly, Yankee Stadium.

Construction began in May 1922—not coincidentally, about the same time the Giants officially handed the Yankees an eviction notice from the Polo Grounds, effective at the end of the 1922 season.

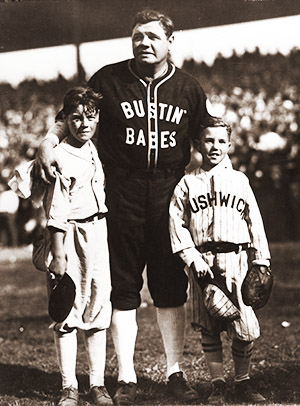

Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis had warned Babe Ruth not to go on a barnstorming tour immediately following the 1921 season; Ruth ignored him and, as a result, was banished for the first six weeks of the 1922 campaign. (The Rucker Archive)

Going into the season, evictions were the furthest thing from the Yankee colonels’ minds.

After the 1921 World Series, Ruth and a few of his teammates, most notably talented outfielder Bob Meusel, quickly headed out on a barnstorming tour for fun and profit outside of their major league establishments. Baseball had drawn up a rule 10 years earlier permitting such tours to take place—provided they didn’t occur immediately after the World Series. Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis warned Ruth and the others to wait, but they defied his command. In his typical swagger, Ruth said of Landis, “To hell with the old goat.”

Ruth and Landis, the two men who had helped trudge baseball out of the depths of the Black Sox Scandal, now became the main event. And Ruth quickly discovered in this clash of titans who reigned more supreme, how uncompromising the first commissioner of baseball truly was.

No meant no. And Landis meant no to the order of a six-week suspension at the beginning of the 1922 season without pay, as well as cancellation of the players’ World Series shares of the year before, at $3,362 apiece. Reprimanded were Ruth, Meusel and pitcher Bill Piercy.

Despite the loss of their two biggest sluggers, the Yankees carried on smoothly without them, anchoring first place when the two returned on May 20. However, Ruth was in no mood; in his first week back, he would be ejected for throwing dirt in an umpire’s face, and then went into the Polo Grounds seats after some fans unmercifully booed him.

BTW: Ruth’s bad behavior cost him the Yankee captaincy, for all it was it worth.

The Yankees as a team had a bigger fight to deal with in the American League race. Their main opposition: The St. Louis Browns.

The franchise that would historically elicit chuckles upon the spoken words of its very name, the Browns were a bona fide powerhouse in 1922, their mightiest outfit until they moved to Baltimore in 1954. For a change, they had strong pitching that went beyond legal spitballer Urban Shocker; they had slugger Ken Williams, whose 39 home runs and 155 runs batted in would momentarily unseat the partially-absent Ruth from the top of the power charts; and they had George Sisler at the top of his game, batting a sensational .420—second in AL history only to Nap Lajoie’s .426 figure in the league’s inaugural 1901 campaign.

Yes, It’s the Best We Could Do

During the 52-year existence of the St. Louis Browns (before the franchise moved to Baltimore), the team managed to finish above .500 just 12 times—the most impressive season of which came in 1922. Below is a list of the Browns’ best five years in St. Louis. Honestly.

That other team at Sportsman’s Park, the St. Louis Cardinals, was also in the thick of a tense National League race with that other Polo Grounds team, the Giants. The Cardinals’ hopes rested more one-dimensionally on the shoulders of Rogers Hornsby, who was on his way to shattering the NL home run mark—he would hit 42—while batting over .400. On the other hand, the Giants had a solid grouping of talent so balanced, everyone in the lineup hit over .320—except third baseman Heinie Groh, who strangely hit a mediocre .265 after manager John McGraw labored extensively to purchase the star hitter from Cincinnati.

BTW: Hornsby, who would also break the NL record for total bases with 450, secured a .401 average by going 3-for-5 on the season’s final day.

McGraw had a harder time trying to keep his pitching staff intact. Among his problems was the dilemma of starter “Shufflin”’ Phil Douglas, the Giants’ best pitcher—and heaviest drinker. An 11-year veteran, Douglas was having a career year—an 11-4 record with a league-leading 2.63 earned run average—yet he detested McGraw for trying to dry him out. He was as angry of the idea of McGraw collecting another pennant as he was hopeful that he could be part of such a winner; so he wrote to Cardinals outfielder Leslie Mann, offering to vacate the Giants for some bucks. Standing in the shadows of the Black Sox Scandal, Mann wanted nothing to do with the letter and immediately had it sent on to Commissioner Landis—who promptly kicked Douglas off the Giants and out of baseball for life.

Pitcher Jack Scott survived major personal and professional obstacles to bounce back late in 1922 and become a key component in the New York Giants’ run to the National League flag. (The Rucker Archive)

Faced with stiff competition from their rivals at St. Louis, the Giants and Yankees went to their friendly, cash-strapped rivals in Boston to take more budget-challenged talent off their hands. The Giants acquired pitcher Hugh McQuillan from the hapless Boston Braves; the Yankees filled a critical hole at third base when they called their friend, Boston Red Sox owner Harry Frazee, and asked for Joe Dugan. For a little more cash, Frazee was happy to oblige the Yankees with yet another of his players.

The moves of the New York clubs not only infuriated the Cardinals and Browns, who didn’t have that kind of money to throw around; civic leaders in St. Louis got into the act as well, wiring complaints to Commissioner Landis. Though there was nothing in the rulebook to force Landis to revoke the purchases, the controversy did lead to the establishing of a June 15 trading deadline starting in 1923.

For now, promise of the new guidelines was too late for the Cardinals. They withered under the increased weight of the Giants’ talent, losing a hold of first place by the end of August. They finished tied for third with Pittsburgh, eight games back of the Giants.

Ironically, the Giants got help in the stretch run from a player no one was interested in. Pitcher Jack Scott, who just a year earlier had led the NL in appearances, suffered a nightmarish offseason in which his arm went dead and his North Carolina farm burned to the ground. Released in spring training by the Reds, Scott sat dormant and destitute until McGraw gave him a tryout. Revitalized, Scott answered the call as if his life depended on it—in a way, it did—winning eight of 10 decisions while saving two more for the Giants in half a season’s work.

BTW: The Reds, finishing seven games back in second place, might have had more of a chance to catch the Giants had future Hall-of-Fame outfielder Edd Roush not held out for most of the season

While the Giants coasted in the season’s waning weeks, the Yankees and Browns performed a nail-biting finish to the wire. Leading early in September, the Yankees were faced with the challenge of playing their final 18 games on the road—including a stop in St. Louis for a crucial three-game series against the Browns.

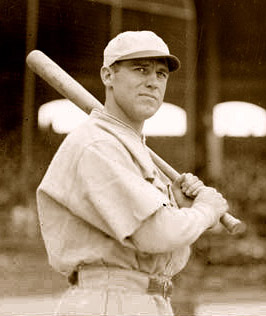

The St. Louis Browns’ chances of toppling the New York Yankees for the American League pennant were imperiled when star hitter George Sisler—who would hit an astounding .420—played hurt down the stretch. (Chicago Historical Society)

Basically swinging with one arm, Sisler managed to hit safely in the first two games against the Yankees to break Cobb’s record at 41 straight; the two teams traded victories. But he also watched helplessly as New York outfielder Whitey Witt, going after a fly late in the first game, was struck in the head by a bottle thrown from a Browns’ fan. Returning bandaged for the final game of the series, Witt extracted revenge by driving home two in the ninth, giving the Yankees not only a 3-2 win but a lead in the AL race they would never relinquish. The bottle-throwing incident depressed the Browns’ spirits, but Sisler’s sore shoulder—which kept him out of action the rest of the year—hurt even more; they finished the season one game back of the Yankees.

BTW: Sisler went hitless in the third game against the Yankees to end the streak at 41 games.

The big World Series rematch between the Giants and Yankees, sharing the Polo Grounds for the last time, was anticlimactic. The Giants swept in four games; the only controversy came in the game that didn’t count—a 3-3 tie in Game Two, stopped after 10 innings due to “darkness,” even though the sun still had an hour to set.

BTW: Commissioner Landis, in an effort to quell suspicions that the two teams were trying to rake in extra gate money, forced the $120,000 taken in during Game Two to be given to charity.

Though a sweep, the Giants’ second straight Series triumph was not a convincing rout. Three times they had to come from behind to tip the Yankees, and their biggest margin of victory was three runs—courtesy of a four-hit shutout by the rediscovered Jack Scott in Game Three. To John McGraw’s utmost satisfaction, Giants pitching nullified Babe Ruth at the plate. Ruth had his second straight World Series of frustration, collecting only a single and double in 17 at-bats. As a team, the Yankees barely managed to hit .200 for the second straight year against the Giants. Offensively, Heinie Groh rose to the occasion following his disappointing regular season by batting .474 for the Giants.

John McGraw could say he was the king again. He had not only brushed the Yankees aside with a World Series sweep and again silenced Babe Ruth in the process, but he also kicked them out of the Polo Grounds for good.

It would be his last hurrah.

Forward to 1923: With Regards to Harry The New York Yankees become one of baseball’s great dynasties at the willful expense of the Boston Red Sox and their Broadway-obsessed owner, Harry Frazee.

Forward to 1923: With Regards to Harry The New York Yankees become one of baseball’s great dynasties at the willful expense of the Boston Red Sox and their Broadway-obsessed owner, Harry Frazee.

Back to 1921: See You at the Polo Grounds The home for both the New York Yankees and Giants becomes the exclusive host to the first Subway Series.

Back to 1921: See You at the Polo Grounds The home for both the New York Yankees and Giants becomes the exclusive host to the first Subway Series.

1922 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1922 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

1922 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1922 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

The 1920s: …And Along Came Babe Baseball becomes the rage thanks to increased offense and the magical presence of Babe Ruth, whose home runs exert a major influence upon the game for ages to come.

The 1920s: …And Along Came Babe Baseball becomes the rage thanks to increased offense and the magical presence of Babe Ruth, whose home runs exert a major influence upon the game for ages to come.