THE YEARLY READER

1923: With Regards to Harry

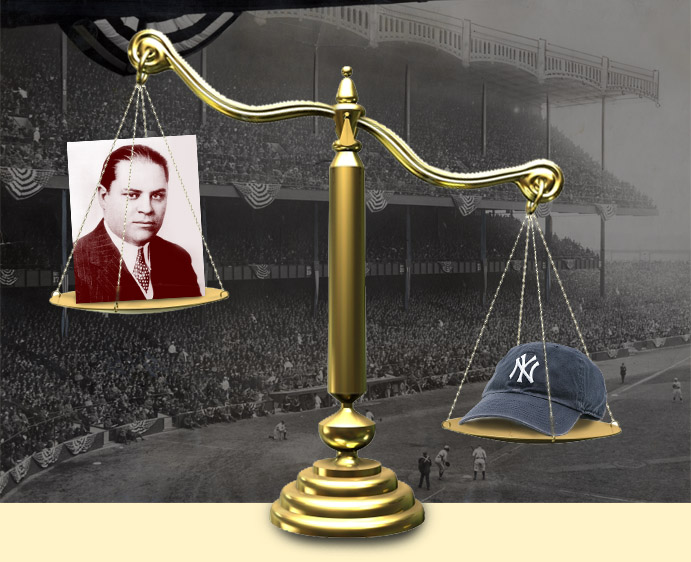

The New York Yankees reach superpower status thanks to their frequent—and generous—trading partner Harry Frazee, who’s engaging in a systematic plundering of his Boston Red Sox to finance his true love of producing shows on Broadway.

Boston owner Harry Frazee (above) increasingly found himself on the lighter end of almost every trade he forged between his Red Sox and the New York Yankees, who used the resulting leverage to help realize Yankee Stadium.

Harry Frazee purchased a champion at Boston. The Red Sox had won three World Series during the 1910s, and in 1918, Frazee’s second year of ownership, they won a fourth. The Red Sox were the darlings of Boston and the envy of baseball.

But baseball was not Frazee’s first love. That was reserved for Broadway. And he cared little for winning ballgames compared to the thrill of producing a hit show.

Yet that blockbuster proved far more elusive than the Red Sox’ ability to win championships. And as he lost money with repeated flops on the stage, he inadvertently created one of the biggest shows in town: The New York Yankees.

When the Yankees captured their first World Series title in 1923, they did so with a roster that included 11 former Red Sox players—all traded for or purchased by the Yankees over a four-year period for lesser quality players and a lot of money to help pay off Frazee’s Broadway debts.

The remains of the weakened Red Sox were headed for a big and sustained fall that would persist over a decade. Conversely, the Yankees launched one of sport’s most powerful reigns, lasting nearly half a century.

Why Frazee would deal almost exclusively with the Yankees didn’t require much thought. A virtual absentee owner in Boston, Frazee held court in New York—close to both Broadway and Yankee headquarters. When he was in a pinch, he would call or perhaps even walk in on Yankee owners Jacob Ruppert and Tillinghast Huston to secure a little extra cash, to ship another ballplayer out of Fenway Park.

Frazee’s first transaction with the Yankees came in 1918 when he traded Duffy Lewis, Ernie Shore and Dutch Leonard—three of Boston’s top players during its championship years—for three common players and $15,000 cash. A year later, surly pitcher Carl Mays bolted from the franchise, and Frazee placated him by shipping him off to New York for two more players of little note—and $40,000.

The unprecedented deal that sent Babe Ruth to the Yankees after 1919 really sent the message that Frazee needed the money, bad. Frazee received $125,000—and an additional $300,000 loan with Fenway Park as collateral. In a feeble attempt to rationalize the selling of a superstar, Frazee pointed to Ruth’s consumptive behavior and believed the Yankees were taking a gamble on him.

BTW: For those not versed in banking terminology, “with Fenway Park on collateral” meant that if Frazee couldn’t pay back the $300,000, the Yankees would take ownership of the Boston ballpark.

The loan would be paid off over the next three years by disposing of top-line talent for bags of currency and various mediocre players. Joining the one-way parade route from Boston to New York were shortstop Everett Scott, third baseman Joe Dugan, catcher Wally Schang, and a bundle of pitching talent that by itself made up the majority of the Yankees’ hurling successes of the 1920s.

Of New York’s 98 victories in 1923, 81 came courtesy of former Red Sox starters: Sad Sam Jones, Herb Pennock, Bullet Joe Bush and Waite Hoyt. The fifth starter in the Yankee rotation, Bob Shawkey, didn’t come from Boston but could relate to the situation; he, along with Pennock and Bush, were refugees of Connie Mack’s fire sale in Philadelphia during the mid-1910s.

The Yankees had it all in 1923; they only lacked the competition. Babe Ruth returned to superstar form after his suspension-laced “off-year” of 1922; their pitching was so stacked, Carl Mays was demoted to the bullpen; and defensively, the Yankees became the first major league team to average less than an error per game.

Behemoth, sparkling new Yankee Stadium opened on cue for the start of the season, and a more appropriate script couldn’t have been written for the opener. Ruth hit the Stadium’s first home run, and the Yankees triumphed, 4-1. The losing team: Frazee’s Red Sox. The new facility was jammed with 64,000 fans, easily the largest crowd to view a major league contest to date; over another 20,000 were turned away.

In what was the biggest mismatch the American League had yet to see, the Yankees squashed any hopes for a pennant race by pulling away to a 16-game finish over second-place Detroit, which as usual had the hitting—but no pitching. The St. Louis Browns, who had nearly unseated the Yankees the year before, were badly set back with the loss of George Sisler, who suffered a sinus infection so serious that it blurred his vision and forced him to miss the entire season. The Browns finished fifth.

The New York Giants, who had helped to make Yankee Stadium a reality by booting the Yankees out of the Polo Grounds the year before, responded to the massive size of the new ballpark across the Harlem River by upgrading their own seating capacity to 55,000. They still couldn’t outdraw the Yankees—200,000 fewer fans came through their turnstiles—but at least they had the ballpark to themselves again.

The two-time defending champs managed to keep pace with their local rival by claiming their third straight National League pennant. The Giants had stiff competition throughout the league, yet still managed to become the first-ever NL team to hold first place from the regular season’s first day to its last. The Cincinnati Reds, with the NL’s best earned run average and three 20-game winners (led by Dolf Luque’s 27-8 record and 1.93 ERA), lacked the punch at the plate and finished 4.5 games back as the Giants’ closest competitor.

Manager John McGraw’s pitchers weren’t as impressive as in years past, but they were a hit at the plate—abetting an explosive everyday lineup. Left-hander Jack Bentley, acquired during the off-season after a seven-year absence from the majors, batted .427 with 38 hits. Jack Scott, who continued his comeback momentum from the previous year, led the Giants with 16 wins—and hit .316 at the plate.

BTW: Bentley was labeled the next Babe Ruth in minor-league Baltimore with outstanding pitching and hitting, but after the Giants bought into it to the tune of $65,000 and three players, he never came close to fulfilling that destiny.

What terrified opponents was that the team’s three best overall hitters—George Kelly, Frankie Frisch and Ross Youngs—were just beginning to reach full maturity as veteran players. They had already done enough damage in years past, and they continued their path of destruction on the rest of the NL in 1923. Frisch and Youngs each had over 200 hits, with Frisch leading the NL at 223; Kelly, batting .307 with 16 home runs, was one of three Giants to reach the century mark in runs batted in with 103. Thirty-year-old left fielder Irish Meusel led the league with 125.

When veteran shortstop Dave Bancroft went down to injury, McGraw reached into his pocket of green talent and sent in yet another future Hall of Famer, 19-year-old Travis Jackson—who hit .275 in 96 games.

Whether he meant to or not, McGraw had a budding protégé platooning in his outfield. Used primarily against right-handed pitching, left-handed hitting Casey Stengel made the most of his part-time role by hitting .339. Furthermore, the 32-year-old veteran was beginning to emulate the feisty McGraw, receiving a 10-day suspension for his role in a nasty fight with Philadelphia Phillies pitcher Phil Weinert in May. During a later game against the Reds, Stengel nearly came to blows with Dolf Luque when he and numerous teammates trash-talked the tempestuous Cuban pitcher to the point that they had to be separated—not by other players, but by the police.

For the third straight year, the World Series matchup was all New York. In advance, the Yankees were desperately hoping to get Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis to bend the rules and allow a late call-up—a young 20-year old from Columbia University who had batted nearly .500 in 13 games for the Yankees—to be made eligible to play against the Giants. Landis said it was fine with him, as long as John McGraw agreed. McGraw, who once tried to recruit the youngster himself, must have felt genuine incredulity at the request and instantly said no.

Hope denied, Henry Louis Gehrig would have to be content at being a bystander and wait another year for a chance at October baseball.

The Giants stepped into Yankee Stadium for the first time in Game One, and Casey Stengel took center stage in a ballpark he would call home many years later. Splitting up a 4-4 tie in the top of the ninth, Stengel raced around the bases with an inside-the-park home run, making the last 90 feet of his journey historic. Stengel’s shoe had come loose as he rounded third, and like a car out of control with a blown tire, he stumbled, limped and flailed his way home, somehow managing to beat the throw.

Colorful as ever, Stengel reprised his heroics in Game Three—the Series’ second game played at the Stadium—by smacking a home run the easy way, over the fence. Rewarded with a relaxed trot around the bases, Stengel answered the jeers of Yankee fans by thumbing his nose at them. Even the usually hardened Landis, watching from the commissioner’s box, waxed bemusement at Stengel’s antics by noting later, “Casey Stengel can’t help being Casey Stengel.”

Alas for the Giants, any chance for a third straight Series triumph would be usurped by Babe Ruth. Frustrated over the previous two years against the Giants, the Sultan of Swat finally rose to the occasion in the Fall Classic. He reached base 15 times throughout the six-game series, with five extra-base hits—and predictably became the first player in Series history to hit three home runs, all solo. Two of his blasts came in a 4-2, Game Two victory for the Yankees at the Polo Grounds; the third was launched as the initial run for the Yankees’ 6-4, series-clinching Game Six win.

Switched on October

In his first five World Series—three of them as a pitcher for the Red Sox—Babe Ruth was a virtual dud at the plate. That changed dramatically in 1923, when the Yankees’ superstar began a continuous non-stop assault on Fall Classic opponents for the balance of his career.

The ex-Sox were at the core of the Yankees’ first world championship. The former Fenway residents hit a combined .318; Pennock and Bush paired up to win three games.

In July 1923, Harry Frazee figured he’d run out of quality players to sell to the Yankees, so he sold the franchise. The Red Sox were bought for $1.5 million by John A. Quinn, a former executive of the St. Louis Browns. If Quinn thought he had escaped futility with the typically woeful Browns, he was about to realize just how badly trashed Frazee had left his new investment. Dry on talent and short on funds, the Dead Sox—as they were sarcastically now labeled—embarked on a thoroughly dark era which would result in 10 straight years of miserable baseball, averaging nearly 100 losses per season. Even when they did recover, their repeated attempts to reach the apex of baseball would remain tantalizingly out of reach.

In 1925, Frazee would finally get his Broadway smash. No No Nanette! became a memorable classic, partially financed with bucks secured from his sale of the Boston Red Sox.

By then, the “Rape of the Red Sox” had been completed. The New York Yankees were the benefactors, using their spoils to begin a prosperity of success that would net 20 World Series championships over the next 40 years.

Forward to 1924: A Couple Bad Hops Better The Washington Senators’ one and only championship comes courtesy of a pebble in front of third base.

Forward to 1924: A Couple Bad Hops Better The Washington Senators’ one and only championship comes courtesy of a pebble in front of third base.

Back to 1922: Yankees Go Home Jealous New York Giant manager John McGraw hands an eviction notice to the suddenly popular New York Yankees.

Back to 1922: Yankees Go Home Jealous New York Giant manager John McGraw hands an eviction notice to the suddenly popular New York Yankees.

1923 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1923 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

1923 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1923 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

The 1920s: …And Along Came Babe Baseball becomes the rage thanks to increased offense and the magical presence of Babe Ruth, whose home runs exert a major influence upon the game for ages to come.

The 1920s: …And Along Came Babe Baseball becomes the rage thanks to increased offense and the magical presence of Babe Ruth, whose home runs exert a major influence upon the game for ages to come.