THE YEARLY READER

1934: Dizzy, Daffy and Ducky

The story of the St. Louis Cardinals’ Gashouse Gang, a roguish bunch who capture the World Series from the Detroit Tigers—but not before causing a near riot during a victorious seventh-game blowout in enemy territory.

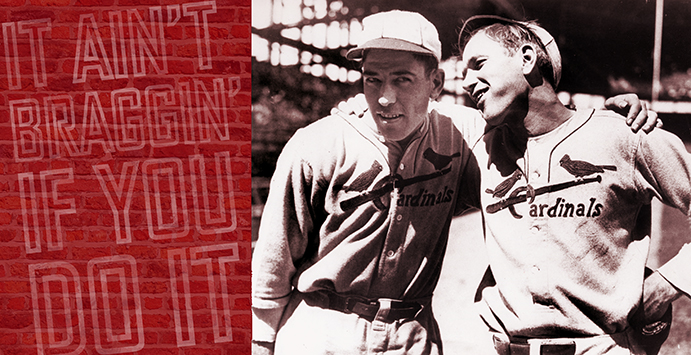

Like two pesky peas in a percolating pod, the swaggering Dizzy Dean (right) and his more humble brother Daffy Dean played the prime movers on a rambunctious St. Louis Cardinals team that bullied its way to a world title. (The Rucker Archive)

Jay Hanna “Dizzy” Dean boastfully spread the news before the 1934 season: He and his rookie brother Paul were gonna gang up and win 45 games together for the St. Louis Cardinals.

And for once in his life, Dizzy sold himself short.

No one could brag and then back up the brash predictions quite like Dizzy Dean. Well before he arrived on the major league scene, he had mastered the art of self-promotion. As his performance in the bigs began to substantiate the talk, the general reaction to Dizzy evolved from sarcastic chuckles to wild praise. His remarkable 1934 campaign, coupled with a solid debut for his little brother, surpassed even Dizzy’s egotistical expectations.

The 1934 St. Louis Cardinals—a reckless batch of ballplayers best remembered as the Gashouse Gang—would greatly benefit from the Deans in the end.

With a deep southern drawl that was short on syntax but long on color, Dizzy Dean never seemed to get his past right with reporters, giving various places and dates of birth. Perhaps that’s why they called him Dizzy. No one quite knew where the nickname came from, either—though Dean had several different versions for that as well.

Raised within a poor rural family, Dizzy was rich in talent, his pitching arm first noticed by St. Louis scouts in 1930—not surprising, since the vast Cardinals farm system Branch Rickey had set up was still miles ahead of any other major league organization. Dean won 25 that first year, rocketing up the minor league chain to the Cardinals for a start on the season’s final day—allowing just three hits in a win over Pittsburgh. Reporters anticipating an excited young Dean in the clubhouse instead found the 19-year old moaning, “Those bums got three hits off’n me.”

Dizzy had the goods to make the starting rotation in 1931, but St. Louis sent him back to the minors—not to work on his mechanics, but his humility. The Cardinals were deeply concerned with Dizzy’s ego—not to mention his gratuitous spending habits.

A year later Dizzy returned to the majors to stay, winning 18 in his rookie year before notching 20 more in 1933. But he remained a thorn in the side of St. Louis management, staging various small holdouts for more money, and at one point declaring himself a free agent because he had signed with the organization while underage.

BTW: The Cardinals got him to admit otherwise when they discovered Dizzy had lied about his age.

Just another day in the life of the Gashouse Gang, joined here by a member of the Chicago Cubs. At far right is Pepper Martin, certainly the most active of pranksters on the Cardinals. (The Rucker Archive)

Dizzy was constantly lobbying to have his brother Paul—also in the St. Louis organization—brought up to the parent club. The Cardinals finally listened after the 19-year-old Paul won 22 games in the minors during 1933. Dizzy championed that only Paul could pitch better than he, and reporters searched for a companion nickname for the much quieter, younger Dean. Harpo made the most sense, but they eventually agreed on Daffy; if for nothing else (and it wasn’t), it was simply poetic license.

Daffy—er, Paul—hated the nickname.

The Cardinals of 1934 were loaded with characters that somehow managed to get along with each other—barely. Within the cast was Pepper Martin, since converted to third base but still the point of origin for the Cardinals’ “Gashouse” persona—and one of its merriest pranksters, spending dead time on the road staging mock fights with teammates in the hotel lobby, then going upstairs to drop bags filled with water upon unsuspecting victims on the sidewalk below.

There was shortstop Leo Durocher, who could have been mistaken for a lightweight boxer—and although he did play that role at times, it wasn’t in the ring. Nicknamed everything from “Leather Player” (Dizzy’s description of a good-field, no-hit player) to “The All-American Out” to the more aptly titled “The Lip,” Durocher quickly became manager Frankie Frisch’s right-hand man in the dugout as training for a fruitful future as skipper. But Durocher was more of an event away from the ballpark than he was within it, thanks to his well-known gambling habits and consorting with questionable types—elements that would shadow his baseball life. He was also in the middle of a messy divorce proceeding, during which he admitted punching out his wife a few times.

Another recent, prominent addition in St. Louis was 22-year-old outfielder Joe Medwick, a potent slugger with an ornery disposition that frequently found him scraping with teammates. Always on the lookout for a good moniker to pin on another, Medwick’s teammates heard that he’d been called “Ducky” in the minors—and it stuck as yet another complement to the Dizzy/Daffy chorus.

Medwick hated his new nickname, too.

The roster was loaded with names—Ripper, Spud, Kiddo, Wild Bill, Tex—that made opponents wonder if they were headed for a ballpark or a back alley. And if Dizzy, Daffy and Ducky weren’t enough, Veteran hurler Dazzy Vance made a late-season appearance for the Gashouse Gang at the age of 43. All in all, it seemed amazing to believe that the architect of this asylum was Branch Rickey, the deeply religious St. Louis general manager who made it a point never to attend games on Sunday.

As a team, the Cardinals ran hot and cold through the 1934 season, the brothers Dean doing all they could to keep the team strong. Off the mound, however, they did plenty to wreck the team’s chemistry.

When Dizzy complained early on that he and Daffy each earned half the salary of pitching teammate Wild Bill Hallahan—claiming they were both twice as good—the other Cardinals pitchers stewed. Then came an exhibition at Detroit in early August. The Deans went AWOL, and when manager Frankie Frisch returned to St. Louis and fined the two, Dizzy and Daffy went crazy. They tore the locker room apart and ripped up their uniforms. When reporters burst in to get the scoop, the Deans, using their self-taught public relations know-how, repeated the scene for the flashbulbs.

The Deans stayed away for a week before realizing this was one dispute they couldn’t win; their teammates started to tire of their antics, and besides, the Cardinals won seven of eight games in their absence.

Down seven games to the front-running New York Giants in early September, the Cardinals—and more importantly, the Deans—finally got serious. In an aggressive stretch run, the Cardinals pared down the lead on September 16 as they swept a doubleheader from the Giants at the Polo Grounds; Dizzy won the first game in a relief role, and Daffy took the nightcap by outdueling Carl Hubbell.

In a more stunning display of a one-two punch five days later at Brooklyn, Dizzy won the first game of a twinbill against the Dodgers with a three-hit shutout—before Daffy one-upped him with a no-hitter in the second game.

BTW: Dizzy claimed afterward that if he knew Daffy was going to throw a no-hitter, he would have thrown one as well. Throughout his entire career, he never did.

Best of the Brethren

The Dean brothers are 1-2 on the all-time list of combined victories by a pair of siblings playing for the same team. (List does not include tandems in which one brother won no games.)

The Dodgers would continue to aid the Cardinals’ cause after the two teams played their final game against one another. All year long, Brooklyn had seethed over preseason comments made by Giants manager Bill Terry, who when asked about the Dodgers’ chances quipped to reporters, “Brooklyn? Are they still in the league?”

BTW: When Dodgers manager Max Carey didn’t act on motivating his team through Terry’s comments, he was fired—and replaced by the colorful Casey Stengel, who was far from likely to stay mum on the subject.

Going into the season’s final weekend, the Cardinals trailed New York by a game with two home contests each left to play: St. Louis against Cincinnati—and the Giants against Brooklyn.

The Deans took over against the Reds. Daffy was masterful on Saturday, winning his 19th game; on Sunday it was Dizzy—throwing his second seven-hit shutout of the Reds in three days. It was his 30th win of the year; no NL pitcher has since reached that peak.

Meanwhile, the Cardinals watched the scoreboard with jubilant astonishment. The Dodgers rallied to take both games from New York, wiping away the Giants’ chances for a second straight NL flag while letting Bill Terry know that, yes, Brooklyn was still in the league.

BTW: For what it’s worth, the Giants easily took the season series against the Dodgers, winning 14 of 22 games.

While St. Louis’ pennant was its fifth in nine years, the Detroit Tigers were returning to the World Series for the first time since 1909 with a more uneventful American League campaign. Under first-year catcher-manager Mickey Cochrane—purchased from under the Philadelphia Athletics’ “Players for Sale” sign—the Tigers usurped defending AL champion Washington with a rather novel approach: By siphoning away some of the Senators’ best talent. Coming over from Washington was veteran outfielder Goose Goslin, who hit .305 with 13 home runs and 100 runs batted in; and for the stretch run, the Tigers obtained 35-year-old pitcher General Crowder, the AL’s two-time defending leader in wins having a rotten year (4-10, 6.79 ERA) in Washington—but a much better one once in Detroit, winning five of six decisions.

The Tigers outlasted the New York Yankees by seven games, while injuries, old age and bad performance in general plummeted Washington down to seventh.

True to form, Dizzy Dean was anything but humble in making his World Series forecast. The Deans would dominate, he gloated, and win all four Series games for the Cardinals.

Once more, Dizzy’s words would ring the truth. He won two of his three starts, losing Game Five 3-1 with a general lack of support from St. Louis bats. Dizzy begged to start Game Seven despite having gone the distance two days earlier, and Frisch gave him the shot. Responding with his best effort yet, Dizzy shut out the Tigers on six hits in the Series-clinching finale. It was his fifth start in 12 days.

Dizzy’s most memorable moment of the Series came when he appeared as, of all things, a pinch runner in Game Four. Running from first on a ground ball, Dizzy was knocked, well, dizzy, when the throw from second nailed him square in the forehead. He was carried off on a stretcher and taken to a hospital where, as one newspaper headline screamed, X-rays of his head revealed nothing.

BTW: The headline may be one of baseball’s great tall tales; researchers have failed to uncover any such phrase in the newspapers of the time.

After getting into a scrap with Detroit’s Marv Owen following a rough slide into third base with the Cardinals comfortably in front, Joe Medwick faces an angry mob of Tigers fans who welcome him back to the outfield with a cascade of fruit and trash. Medwick was removed from the game for his own safety. (The Rucker Archive)

Daffy was Dizzy’s equal, if not better, in his two starts. He won Games Three and Six, quietly allowing just two earned runs.

The performance of the Deans during the World Series was nearly overshadowed by a riotous situation in Game Seven, ignited by Ducky Medwick.

Having all but locked up the Series with a 7-0 lead in the sixth inning, Medwick aggressively legged out a triple, sliding hard into third—and Detroit third baseman Marv Owen, who was clipped to the ground. With tensions already high from the constant bench-jockeying emanating from the St. Louis players, Owen and Medwick instantly tangled before being quickly separated. The Detroit fans, angered that Medwick’s overzealous slide was a sign the Cardinals were rubbing it in, let Ducky have it when he returned to the outfield for the next inning; bottles, fruit, scorecards—anything the spectators could dig up—littered the field around him. Each time the field crew cleaned it up, the fans simply littered it again.

After 20 minutes, Medwick was finally called over by commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis, seated near the St. Louis dugout; after refusing Landis’ request to shake Owen’s hand to quell the crowd, Landis ordered Medwick off the field to avoid a potentially embarrassing forfeit of a World Series finale. Medwick reluctantly complied, slamming his mitt to the ground as he stormed into the dugout.

The Cardinals would take the championship, but the year belonged to the Deans. Dizzy had promised up to 45 victories from himself and Daffy, and delivered 49—and four World Series wins on top of that.

Dizzy would never apologize for his grandiose predictions, stating: “It ain’t bragging if you do it.”

Forward to 1935: The Babe’s Bittersweet Bow Out Babe Ruth’s final year in the majors is full of decline, frustration—and one last marvel of immortality.

Forward to 1935: The Babe’s Bittersweet Bow Out Babe Ruth’s final year in the majors is full of decline, frustration—and one last marvel of immortality.

Back to 1933: Making Little Napoleon Proud An ailing John McGraw hands the managerial reins to first baseman Bill Terry—who promptly rides the New York Giants back to triumph.

Back to 1933: Making Little Napoleon Proud An ailing John McGraw hands the managerial reins to first baseman Bill Terry—who promptly rides the New York Giants back to triumph.

1934 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1934 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

1934 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1934 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

The 1930s: Dog Days of the Depression The majors take a hit from the Great Depression as both attendance and bravado are on the wane—until newborn icons Joe DiMaggio and Ted Williams emerge to rejuvenate the game’s passion for the fans.

The 1930s: Dog Days of the Depression The majors take a hit from the Great Depression as both attendance and bravado are on the wane—until newborn icons Joe DiMaggio and Ted Williams emerge to rejuvenate the game’s passion for the fans.