THE YEARLY READER

1940: Victorious Healings

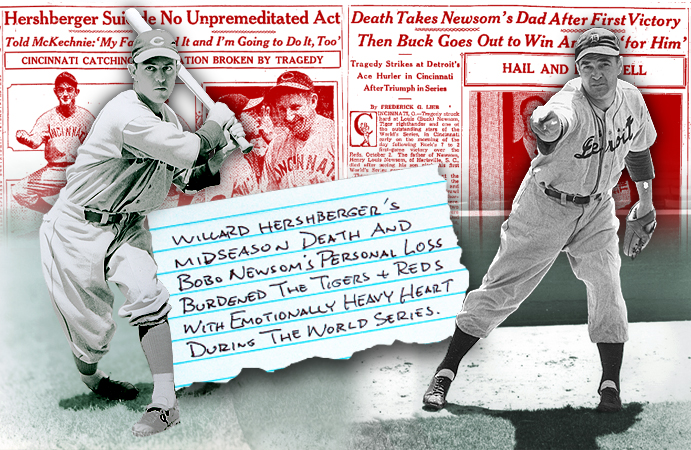

A tragic suicide provides a focused backdrop for the Cincinnati Reds in a seven-game World Series against the Detroit Tigers—whose star pitcher, Bobo Newsom, is also beset with recent personal loss.

When Thomas Newsom left his home in South Carolina to see his son pitch in the 1940 World Series, he told his friends that he wouldn’t be coming back.

Whatever he meant with those words, Thomas fulfilled his prophecy with melancholy consequence. Watching Bobo Newsom put away the Cincinnati Reds in Game One of the Fall Classic, the elder Newsom repaired to his Detroit hotel room for the evening—and was found dead the next morning, the victim of a heart attack.

A crushed Bobo Newsom stated that his father had passed on because he had lived long enough to see his son win a World Series game. Bobo dedicated the rest of the Series to his dad, then went out and poured his heart and soul into an astounding pair of pitching efforts for the Detroit Tigers.

But in the end, Bobo’s personal triumphs on the mound could not help the Tigers overcome the Reds, overwrought with emotional struggles of their own.

Repeating as National League champs, the Reds often found themselves fighting hard to win, deciding 41 of their 100 victories by a single run—a NL record for the time. But the pennant race was anything but a cliffhanger; Cincinnati coasted to a 12-game finish over the rapidly improving Brooklyn Dodgers.

On paper, the Reds were a virtual carbon copy of the 1939 edition. The team’s strength lay in its pitching, again anchored by veterans Bucky Walters (a league-leading 22 wins and 2.48 earned run average) and Paul Derringer (20 wins, 3.06 ERA). First baseman Frank McCormick was the main gunner at the plate, batting .309 with 127 runs batted in while becoming the third Cincinnati player in three years to win the NL’s Most Valuable Player award.

BTW: St. Louis’ Johnny Mize had a more statistically powerful year, but the MVP vote has never been dictated solely by the numbers—especially in this era.

Catcher Ernie Lombardi, the first of those three Cincinnati MVPs, had succumbed to injuries midway through the season and gave way to his back-up, Willard Hershberger—a 30-year-old former New York Yankees prospect with decent defensive skills and an outstanding eye at the plate. Hershberger had performed marvelously in spot duty for the Reds, consistently batting over .300 while rarely striking out. But he also suffered from fits of depression and had lost his father to suicide 12 years earlier. The rigors and responsibility of calling a game behind the plate was pressure enough; Hershberger thus became one of Cincinnati manager Bill McKechnie’s more carefully watched and consoled players on his roster.

Alas, McKechnie’s mentoring wouldn’t be enough. With Lombardi out, the burden upon Hershberger became heavier, and he began acting more emotionally despondent when the Reds lost games he felt responsible for. In one game at New York, Cincinnati lost in the ninth inning as Hershberger called for a Bucky Walters fastball—which the Giants’ Harry Danning put into the seats to cap a four-run rally.

Four days later, Hershberger did not report to the clubhouse for a game at Boston. A team executive was summoned to the hotel where a shocking discovery was made: Hershberger, dead in his bathroom, his jugular vein severed by a razor blade.

The death was ruled a suicide. No note was found.

As the team recovered from this horrifying episode, they discovered healing from within. Jimmie Wilson, a catching mainstay for the pennant-winning St. Louis Cardinals teams of 1929-31 and now a coach with the Reds, volunteered to activate himself as the new back-up. At age 40, Wilson hadn’t played regularly since 1936, but lent enough experience and sage to steer the other Cincinnati players through a difficult moment and on to the World Series.

The big news awaiting the Reds in October would be the absence of the Yankees.

The four-time defending world champions tripped out of the starting gate in 1940, sticking to last place in May before re-emerging late into the American League pennant race, where they bowed out in the season’s final week. Everything from age to overconfidence was blamed for the Yankees’ woes, and a New York Daily News column even went so far as to suggest that a case of polio spread by Lou Gehrig had infected the players and their performance. As enraged Yankees players prepared to sue, the newspaper detracted the comments and apologized.

The Yankees’ poorest showing in 10 years was, in fact, the by-product of a roster that suffered an off-year at the plate, as mirrored in the team’s .259 batting average—dead last in the AL, and a 30-point drop-off from 1939. In their absence, the Cleveland Indians took over first place for much of the year, but not for a lack of discord. An organization whose players held the strange habit of rejecting their managers—even the highly likeable Walter Johnson had been ousted a few years earlier by a player revolt—the Indians dove into the thick of their biggest controversy yet in June over current manager Ossie Vitt.

Confronting owner Alva Bradley and demanding Vitt’s removal, Indians players claimed the Cleveland manager’s “jittery” dugout behavior was loaded with “insincerity and caustic criticism” that ruined the players’ morale. Bradley did not immediately back his manager, saying he would investigate the matter; that became a moot point, for the moment, when the players publicly took back their wish to have Vitt fired after Cleveland fans weighed in and heavily sided with Vitt.

Despite the unavoidable tension created inside the Indians’ clubhouse, the team held onto first place by four games going into September. But nine games between the Indians and second-place Detroit remained—and the Tigers were heating up for the stretch run.

Star Detroit slugger Hank Greenberg helps the Cleveland Stadium grounds crew collect trash off the field thrown by a raucous crowd during the Tigers’ 2-0 win over the Indians that clinched the AL pennant with two games to spare. (The Rucker Archive)

The teams met one more time for a three-game series at Cleveland in the season’s final weekend. Now down by two games, the Indians needed a sweep, and felt they had a gimmie for the first contest: Bob Feller and his 27-10 record against Floyd Giebell—making only his second major league start after pitching to a 15-17 record at Triple-A Buffalo. Even Detroit manager Del Baker was ready to concede, hoping to save his best pitchers for the final two games.

But Giebell threw the surprise of the year and immediately sealed the Indians’ fate. He outdueled Feller 2-0 in front of a rowdy Cleveland crowd of 45,000, allowing just three hits.

It was the third, and last, victory of Giebell’s major league career.

The consolation prize for Indians players came in the firing of Ossie Vitt. Frustrated and openly critical of the Cleveland front office for not being firmly supportive during the player revolt, Vitt was released after the season—never to manage in the big leagues again.

While Vitt was shown the exit door, The Tigers were entering their third World Series appearance in seven years; it was the first ride for 67-year-old Del Baker, a one-time bench player for the Tigers during the mid-1910s who took over for Mickey Cochrane two years earlier. His masterstroke of strategy in 1940 was figuring out what to do with Rudy York, a muscular, prodigious slugger who showed far less talent on defense. Baker liked York at first base, but that was superstar Hank Greenberg’s domain. Kindly asked to move to the outfield, Greenberg obliged only after the Tigers dangled a pay raise in front of him; both he and York responded with a tremendous double whammy that pummeled the opposition. Greenberg led the AL with 41 home runs and 150 RBIs, while York added 33 home runs and 134 RBIs while finally playing everyday.

BTW: Both Greenberg (.340) and York (.316) set career highs in batting average.

The Detroit pitching staff was anchored by Bobo Newsom, a talented Southerner who rolled off his best year ever with 21 wins, five losses and a 2.83 ERA. Perhaps more amazingly, Newsom started and finished the year with the same team.

Teammates of Babe Ruth once joked that they roomed with his suitcase. Bobo Newsom lived out of his suitcase. His 20-year big league career would keep the moving industry profitable, changing his address 17 times, playing for nine different teams, many of them more than once—including five separate stays in Washington. His colorful yet hard-edged demeanor would help precipitate many of his trades.

Bobo on the Go-Go

In a career that spanned 25 years and included pitching encounters against both Babe Ruth and Mickey Mantle, Bobo Newsom would become the game’s most transitory player of his time—switching uniforms 17 different times, including nine mid-season exchanges.

When Newsom’s father died following his son’s complete game victory to open the World Series, the Tigers weren’t sure how Bobo would respond with his next start in Game Five. They were pleased to see a pitcher who was completely focused and emotionally intent on delivering again for his father; Newsom blanked the Reds on a sharp three-hitter, backed by seven early runs from Detroit bats in an 8-0 whitewash.

When Bucky Walters returned the favor the next day and shut down Detroit, 3-0, the Series headed for Game Seven. The Reds were prepared to send Paul Derringer to the mound on just two days’ rest.

After some hard thinking, Del Baker countered by sending Newsom back to the mound—on one day’s rest.

On pure emotional gas and whatever strength he had left, Newsom got an early, slim 1-0 lead and held it up for six innings. But the first two Cincinnati batters of the seventh, Frank McCormick and Jimmy Ripple, doubled and eventually scored all that was needed for Derringer to finish up. It was one of the great pitching finales in World Series history; Derringer and Newsom both went the distance on short notice, and the Reds emerged as a 2-1 winner.

With Ernie Lombardi’s ankle badly hurt, Jimmie Wilson came to the rescue once more. Taking over the catching reins and helping to ease the sorrow over Willard Hershberger’s death, Wilson batted .353, played well defensively and stole the Series’ only base; he even labored with a pulled leg muscle in the final two games. It was his last action as a major league player, moving on to Chicago to become the Cubs’ manager in 1941.

Cincinnati’s victory gave the National League its first World Series championship in six years. It also represented the Reds’ second-ever world title—though many would argue it was their first true title, given the scenario of their previous “triumph”—in 1919, when they defeated a half-honest Chicago White Sox ballclub.

Forward to 1941: 56, .406 and Dem Bums Joe DiMaggio’s magical hitting streak, Ted Williams’ run at .400 and the rise of the Dodgers result in one of baseball’s most memorable years.

Forward to 1941: 56, .406 and Dem Bums Joe DiMaggio’s magical hitting streak, Ted Williams’ run at .400 and the rise of the Dodgers result in one of baseball’s most memorable years.

Back to 1939: Farewell, Iron Horse His game rapidly deteriorating, Lou Gehrig pulls himself out of the lineup—never to play again.

Back to 1939: Farewell, Iron Horse His game rapidly deteriorating, Lou Gehrig pulls himself out of the lineup—never to play again.

1940 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1940 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

1940 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1940 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

The 1940s: Of Rations and Spoils The return to a healthy economy and the breaking of the color barrier helps baseball reach an explosive new level of popularity—but not before enduring with America the hardship and sacrifice of World War II.

The 1940s: Of Rations and Spoils The return to a healthy economy and the breaking of the color barrier helps baseball reach an explosive new level of popularity—but not before enduring with America the hardship and sacrifice of World War II.