THE YEARLY READER

1944: Meet Us in St. Louis

As World War II reaches its peak and its impact on baseball, the typically inept St. Louis Browns reach the World Series for the only time in their existence—but remain the second best team in town.

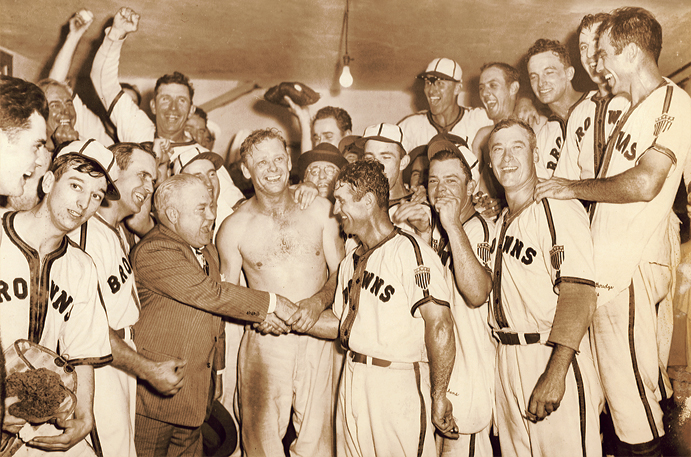

A rare triumph calls for a rare celebration: Members of the 1944 St. Louis Browns let loose after winning the team’s first and only American League pennant. Awaiting them in the World Series would be the crosstown Cardinals, who would have the final say. (The Rucker Archive)

The St. Louis Browns had never won anything in their life. They had never been to the World Series. In fact, the Browns seldom even came close. Only in 1922 did the Browns field a team worthy of an American League pennant, but they still couldn’t win; they finished a mere game behind an emerging New York Yankees dynasty.

The Browns’ ineptitude on the field was reflected in their gate receipts. Only once in the previous 16 years had the team surpassed 300,000 in attendance, once drawing as little as 80,000 for an entire year; for one 1933 contest, a crowd of 34 showed up. It was an organization often labeled the Siberia of Baseball.

Even when the Browns tried to flee St. Louis, they still couldn’t win. At the end of 1941 they had all but packed their bags for a move west to Los Angeles—until the Japanese invasion at Pearl Harbor railroaded their plans.

Although World War II would keep the Browns shackled in St. Louis, it would give them a competitive boost. The Browns finished third during baseball’s first wartime season of 1942 and, with a roster loaded with players technically rejected for military service, they finally made a successful run at the AL flag in 1944.

Yet they still couldn’t win: When they reached the World Series, the Browns quickly realized that they were still the second best team in town.

Those other tenants at Sportsman’s Park, the St. Louis Cardinals, made no mistake about it; they were the kings of wartime baseball. They had thoroughly dominated the National League for over two years, and the numbers alone proved it. In 1944, the Cardinals dismantled the challengers early and reached the end of August with a stunning 91-30 record; that gave the team a 239-87 mark dating back to the start of their blazing finish in 1942.

The luck of the draw helped to keep St. Louis as a dominant force, its star players not having traded Cardinals uniforms for those of the Armed Forces. Most thankfully for the Cardinals, Stan Musial stuck around and continued to be the league’s most productive player at the plate—batting .347 with a NL-high 77 extra base hits. Johnny Hopp, a sharp left-handed hitter who would spend the bulk of his 14-year career platooning in the lineup, got a rare shot at everyday activity in 1944 and responded by hitting .336—second on the team behind Musial, and fourth in the NL.

The Brothers Cooper also did not receive a call from the military and stayed intact. Walker Cooper batted .317 with 13 home runs and 72 runs batted in through 112 games; his brother Mort pitched his way to a 22-7 record, giving him a three-year mark of 65-22. Along with Cooper, three other regular starters in St. Louis finished with an earned run average under 3.00—and a fifth, George Munger, was 11-2 with a 1.34 ERA before the military managed to nab him midway through the summer.

BTW: The NL MVP Award went to one Cardinal—shortstop Marty Marion—who hardly stood out statistically; regularly batting eighth in the lineup, Marion hit an ordinary .267 with six homers, but his defense was sensational.

Four prime components to the 1944 Cardinals, from left to right: Third baseman Whitey Kurowski, shortstop and NL MVP Marty Marion, future Hall of Famer Stan Musial and first baseman Ray Sanders. (The Rucker Archive)

While roster depth and good fortune with the draft board continued to be the Cardinals’ best friends, it was not the case with most other major league teams. With rosters being eaten alive by the military, teams scurried to find whoever could best fit the bill as a major leaguer. There were some serious stretches being made. Teenagers were becoming more of a common sight—as were rookies over the age of 40.

At Philadelphia, a 17-year-old pitcher named Carl Scheib relieved in 15 games for the A’s. It was his second big league season; a year earlier, Scheib had become the youngest player to date ever to appear in a major league game. The Brooklyn Dodgers added to their roster 16-year-old shortstop Tommy Brown, who showed his age by batting just .164 with no home runs in 46 games. But the Cincinnati Reds had them all beat when, in June, they sent to the mound Joe Nuxhall—a 15-year-old kid who was not even halfway through high school. Thrown into the major league fire for the first time against, of all teams, the Cardinals, Nuxhall got two outs—but also allowed two hits, five walks, and five runs before being removed.

BTW: Nuxhall returned to high school and would have to live with a career 67.50 ERA until he came back to the majors in 1952, a sharper and more mature pitcher.

Kids and Grandfathers Welcome, Too

The final two years of wartime baseball would see a sharp rise in major leaguers listed under 20 years of age, as well as those 40 and above.

On the other side of prime time were the elders. Players approaching or beyond 40 years of age were able to stick around when a full-strength, peacetime major league roster wouldn’t have given them the time of day. Others came back out of retirement, hoping they might have some competitive fight left against a handicapped supply of baseball talent. Former Pittsburgh star Lloyd Waner returned and joined his 41-year-old brother Paul at Brooklyn, while 1931 World Series hero Pepper Martin came back to the Cardinals four years after having last played in the majors, batting a respectable .279 in 40 games for the NL champs.

Available baseball talent had become so scarce at the height of World War II, the Cincinnati Reds briefly brought on 15-year-old Joe Nuxhall, seated here next to manager Bill McKechnie. He lasted just one appearance, but returned to the Reds eight years later for a much longer stay. (The Rucker Archive)

The 4F classification would be a godsend for the St. Louis Browns, who just happened to have 18 such players on their team in 1944.

The general makeup of the Browns’ roster was a classic reflection on the state of the game during World War II. There were pitchers Nels Potter and Jack Kramer, considered washed up after subpar stints during the late 1930s, but now making good on a second chance. Infielders Don Gutteridge and Mark Christman, both out of the majors after 1940, were back in simply because they were available. Outfielder Milt Byrnes was playing full-time in the second of what would be his only three years of big league ball, all during the war. Pitcher Denny Galehouse, a mediocre pitcher before the war who looked better during, was available on Sundays since it was his day off from wartime employment at nearby Akron, Ohio. And there was shortstop Vern Stephens, a genuine talent who was hanging around because he had been classified 4F with a bad knee.

Last and once least was pitcher Sid Jakucki. His only major league experience came eight years earlier when he struggled to a 0-3 record and an 8.71 ERA for the 1936 Browns. Nonetheless, Jakucki was given a new lease on big league life after he was found playing semipro ball in Houston.

When this ragtag batch of once-and-current major leaguers won their first nine games on the year, people joked that the standings were being printed upside down. Remaining near or at the top throughout the year, the Browns watched as the competition within the AL began to wither away to mid-season military deferment. The Boston Red Sox came on strong, only to be sapped by the draft—laying claim to productive hitters in Bobby Doerr and Jim Tabor, as well as pitcher Tex Hughson, who left late in the year with an 18-5 record and 2.26 ERA.

One team that stayed tight with the Browns to the very finish was the Detroit Tigers—blessed with the double-barreled pitching sensation of Hal Newhouser and Dizzy Trout, a pair of 4F cases who between them won a stunning 56 games. The midseason loss of outfielder Dick Wakefield—on his way to a possible triple crown—likely deprived the Tigers of taking control of the AL, forcing them into a dogfight with the Browns.

Trailing the Tigers by a game going into the season’s final weekend—and with the New York Yankees coming to St. Louis for the year’s last four games—the Browns capitalized on their rare case of pennant fever. While Detroit split the first two games in a doubleheader against Washington, the Browns swept the Yankees in a twinbill as the two former rejects, Jack Kramer and Nels Potter, each earned a win by allowing a combined total of one run. After the Browns and Tigers both won the next day to remain tied for first, it was Detroit who lost its final game to the Senators—leaving the Browns’ destiny in their own hands as they took the field against the Yankees for their last game.

A rare opportunity called for a rare sellout at Sportsman’s Park, the first in 20 years for the Browns; 15,000 were turned away. St. Louis starter Sid Jakucki, known to be more than a recreational drinker, was literally locked away in his hotel room the night before to keep from loosening up at the bar.

After trailing early, 2-0, the Browns evened the score with the help of a home run from Chet Laabs—another player who split his time between the Browns and war-related employment. Laabs then broke the tie with another blast—just his fifth of the year—and aided with Vern Stephens’ late insurance homer, Jakucki did his part in silencing the Yankees the rest of the way. The Browns won the game—and the only AL flag they would ever conquer.

Even in triumph, there was a tinge of shame placed upon the Browns’ pennant-winning performance for the record book; their 89-65 effort would go down as the worst by an AL champion to date.

BTW: The Browns were remarkably consistent against AL competition, winning anywhere from 12-to-14 games each against the other seven ballclubs.

Prodigious Pitching Pairs

Although the double-barreled 1944 success of Hal Newhouser and Dizzy Trout didn’t qualify them at the top of the list below, it should be noted that the two Detroit hurlers represent the lone duo whose achievement took place after the Deadball Era.

And what of the Yankees, AL pennant winners over baseball’s first two wartime campaigns? With no-namers like Mike Milosevich, Oscar Grimes, Bob Methany and Hersh Martin in the everyday lineup, a third straight pennant wasn’t going to happen. The Yankees finished third, six games back.

Travel restrictions would thankfully not be a problem at the World Series; it was the first (and last) Fall Classic to be played exclusively at the same ballpark in 22 years.

The Browns’ magic of 1944 would come to an end against their superior co-tenants at Sportsman’s Park, the Cardinals—but not before giving it a good ride early on. The Browns took two of the first three games, with only a 10-inning victory eked out by the Cardinals in between.

But the Cardinals were ultimately just too good for the Browns, thanks to a pitching staff that seized the momentum. The Browns were limited to just two runs over the final three contests—all losses—and the Cardinals, after their shaky start, would capture their second wartime Series championship.

Poor hitting and defense befell the Browns throughout the Series. They batted just .183 as a team, struck out 49 times in just 197 at-bats and committed 10 errors that led to seven unearned Cardinals runs.

Just when they had commanded the proper attention, the Browns’ singular moment in the spotlight crashed in a display of bad baseball more befitting of their years of woe. It was a denial of victory in the first, last and only World Series appearance the St. Louis Browns would ever know.

Forward to 1945: Hank’s Heroic Return As World War II comes to an end, Hank Greenberg makes the first and most celebrated return to baseball.

Forward to 1945: Hank’s Heroic Return As World War II comes to an end, Hank Greenberg makes the first and most celebrated return to baseball.

Back to 1943: War and Games World War II begins to exact a heavy impact on baseball’s ability to play on.

Back to 1943: War and Games World War II begins to exact a heavy impact on baseball’s ability to play on.

1944 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1944 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

1944 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1944 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

The 1940s: Of Rations and Spoils The return to a healthy economy and the breaking of the color barrier helps baseball reach an explosive new level of popularity—but not before enduring with America the hardship and sacrifice of World War II.

The 1940s: Of Rations and Spoils The return to a healthy economy and the breaking of the color barrier helps baseball reach an explosive new level of popularity—but not before enduring with America the hardship and sacrifice of World War II.

Freddy Schmidt talks about the rough road to the majors, playing for two championship teams in St. Louis, and Ben Chapman.

Freddy Schmidt talks about the rough road to the majors, playing for two championship teams in St. Louis, and Ben Chapman. Eddie Carnett discusses a life in baseball during World War II, his limitations on the nightlife and a day he nearly came to blows with Casey Stengel.

Eddie Carnett discusses a life in baseball during World War II, his limitations on the nightlife and a day he nearly came to blows with Casey Stengel.