THE YEARLY READER

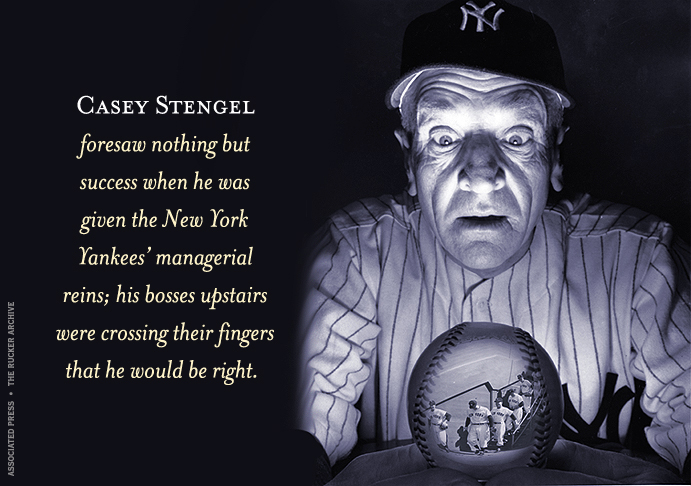

1949: Casey at the Helm

The New York Yankees return to the top of the baseball world with the unlikely help of Casey Stengel, the animated manager whose previous, distant major league experience consisted of one losing season after another.

It seemed like the classic case of opposites attracting. At one end of the spectrum were the New York Yankees, the no-nonsense, cold-as-steel corporate baseball entity that considered anything less than a World Series championship to be an utter disgrace.

At the other end was their new manager, Casey Stengel, a crusty-looking old man with a Vaudevillian sense of humor and a resume of big league managing that consisted of nine lower division finishes.

Disbelief ran a healthy course when news of Stengel’s hiring hit the papers. Boston sportswriter Dave Egan, who frequently targeted Stengel with a poison pen when he managed the Braves, sarcastically reflected the thoughts of many others when he wrote that Stengel’s hiring mathematically eliminated the Yankees from the 1949 American League pennant.

Yet when the season was done, the 58-year old personification of a lovable shaggy dog who made everyone laugh would himself get the last laugh—with a whole lot more to follow.

Granted, Stengel had just won a pennant the year before—managing the Oakland Oaks of the Pacific Coast League. But this was the majors, and these were the Yankees, even if they had become a collection of oft-injured, aging veterans. Yet after the Yankees placed third in 1948 under Bucky Harris—their fourth manager in three years—the proverbial Grim Reaper began to emerge from the fans and press, ready to declare death upon the Yankee dynasty. The arrival of Stengel begged reinforcement of that opinion; when The Sporting News asked over 200 sportswriters on whom they believed would win the AL pennant in 1949, only six picked the Yankees.

Stengel’s biggest fan in the Yankees organization was general manager George Weiss, who had to convince New York owners Dan Topping and Del Webb that underneath Stengel’s goofy persona lay an intense and very clear knowledge of the game. Weiss also argued that Stengel could never win at Brooklyn or Boston because they were clubs that, at the time, had limited muscle for Casey to work his magic with. The Yankees, he noted, had no such issues.

Those vast Yankees assets looked more and more like damaged goods as Stengel progressed through his first year at the wheel. No one seemed healthy. Worst off was Joe DiMaggio, whose slow recovery from offseason surgery to his right heel kept him indefinitely out of action through the spring. Only shortstop Phil Rizzuto could survive as the only everyday Yankee actually playing every day. The list of injuries became so long and talked about, the front office decided to start an official tally as press release fodder; at season’s end, the count stood at 71.

BTW: Rizzuto’s 153 games were distantly followed by second baseman Jerry Coleman, at 128. No other Yankee played more than 116.

Through his years of managing, Stengel had embraced the concept of platooning, something he had learned playing for John McGraw and the New York Giants in the 1920s and that, even now, few other managers were taking very seriously. With the Yankees roster resembling the walking wounded, Stengel’s platooning was suddenly more of a necessity than a luxury. But it worked; the Yankees started in first place and stayed there into June. And then DiMaggio came back; his heel suddenly pain-free, the Yankee Clipper made for an explosively belated season debut when he clubbed four home runs and knocked in nine during a three-game sweep of the rival Red Sox at Boston.

At that point, the Red Sox—most everyone’s odds-on favorites to win the AL—appeared to have received the knockout blow, falling 12 games back of the Yankees by the Fourth of July. Yet they bounced back up and started punching away at the margin, winning 37 of their next 47 to keep the Yankees sweating. By late September, the Red Sox caught up and surpassed New York when they capped an 11-game win streak with their own three-game sweep of the Yankees—who had just lost DiMaggio again, this time to a stubborn bout with pneumonia.

BTW: DiMaggio’s half-season of activity came with a $100,000 salary, which made him the first player ever to earn six figures in one season.

The Red Sox thrived through a small cluster of star performers who packed enormous firepower, offsetting an otherwise inconsistent roster. Not surprisingly, Ted Williams led this short list by batting .342 while setting career highs with 43 home runs and 159 runs batted in. Shortstop Vern Stephens, in his second year removed from the woebegone St. Louis Browns, matched Williams RBI for RBI while smashing 39 homers of his own. On the mound, the Red Sox relied heavily down the stretch on a pair of pitchers who perhaps were the two most productive in the AL: Left-hander Mel Parnell, the league leader in wins (25) and earned run average (2.77); and right-hander Ellis Kinder, another refugee from the Browns, who won 23 while losing only six.

Boston held onto a one-game lead going into the season’s final two contests—at New York. Things looked promising for the Red Sox in the first encounter when they quickly put four runs on the board and knocked Yankees starter Allie Reynolds into the showers. But reliever Joe Page shut the Red Sox down the rest of the way while the Yankees scratched and clawed their way back, eventually winning 5-4 with a pinch-hit solo home run by Johnny Lindell in the bottom of the eighth. In the winner-take-all finale the next day, the Yankees pulled away late and held off a ninth-inning rally to win, 5-3, and grab the AL pennant for Casey Stengel. It was an unbearable moment for the Red Sox; for the second straight year, their chance to snatch the pennant was rebuffed on the season’s final day.

As Stengel jigged for joy in triumph, he could save his biggest thanks for the one group of players that managed to stay healthy all year long: His starting rotation. Led by Vic Raschi (21-10 record) and Allie Reynolds (17-6), Stengel’s four main hurlers stayed resilient and effective all year long; when they did slip, Joe Page was often there to bail them out, racking up a then-record 27 saves while winning 13 more.

Left eight games back in the dust from one of baseball’s most celebrated pennant races would be the defending champion Cleveland Indians, who fell back to Earth after their explosive success of the year before. But Bill Veeck made the most of it; in a memorable promotional stunt, the Indians owner held a pregame ceremony in which the team’s pennant hopes were “buried” in a mock funeral service.

Less remembered than the AL race—yet just as stunning—would be a battle for the National League every bit as intense, featuring two clubs that had developed a habit of fighting one another down to the wire: The Brooklyn Dodgers and the St. Louis Cardinals.

Regrouping after a rocky 1948, the Dodgers were strengthened by a group of young players molding themselves together as the famed “Boys of Summer” that would create the purest of Brooklyn baseball memories. Getting their first swing at everyday play would be center fielder Duke Snider, batting .292 with 23 home runs; Roy Campanella (.287, 22 homers), a short yet powerfully built catcher who followed Jackie Robinson as the Dodgers’ second big-time black star; and 22-year-old rookie pitcher Don Newcombe, another African-American who joined the club in late May and led the Dodgers with 17 wins.

BTW: Newcombe threw the first shutout by a NL pitcher making his debut since 1938.

Jackie Robinson, now the veteran guidance of the Dodgers, no longer sensed being the outsider he was two years earlier when he endured his harrowing major league baptism. The hunted now became the hunter, and Robinson let opposing teams know about it. His numbers on the year certainly spoke for themselves. Batting .342 with 16 homers, 124 RBIs and 37 stolen bases, Robinson’s impressive statistical package easily won him NL Most Valuable Player honors.

Short on Numbers, But not on Quality

Jackie Robinson’s MVP performance in 1949 certainly gave legitimacy to advocates of baseball’s racial integration, but it was just the beginning of an impressive trend; starting with Robinson, 16 of the next 21 National League MVPs would be presented to African-Americans. In stark contrast, the American League—notoriously slow to integrate—gave only three of its MVP awards to blacks during this same time, the first of which wasn’t given out until the Yankees’ Elston Howard was rewarded in 1963.

For all of their rejuvenation, the Dodgers still spent much of the late summer trying to keep pace with the Cardinals, a veteran squad with an undeniable superstar of their own in Stan Musial. With marquee statistics—a .338 batting average, 36 homers and 123 RBIs—every bit the equal of Robinson’s, Musial helped fuel the tight St. Louis edge on Brooklyn all the way to the season’s final week, which they entered with a game-and-a-half lead. Then they crashed. The Cardinals went to lowly Pittsburgh for two games. They lost both. Then they went to lowly Chicago for two more games. They lost those two as well. The Dodgers snagged the lead and had to sweat out an extra-inning triumph on the season’s last day at Philadelphia to avoid a second tie-breaking playoff against the Cardinals in four years.

As a team, St. Louis may have hit better (.277) and pitched better (3.44 ERA) than anyone else in the NL, but the numbers couldn’t translate into a pennant.

Dropping like a rock, the Boston Braves fell from first to under .500. The defending NL champs suffered from internal tension as players badly wanted manager Billy Southworth to be shown the exit door. In August, Braves management made good on their request.

Casey Stengel had been in the thick of the World Series thrice before as a player—most memorably with his home run theatrics for the Giants in 1923. Now he was ready to prove his championship mettle as a manager for the Yankees, an organization hoping to quiet the preseason critics into early hibernation.

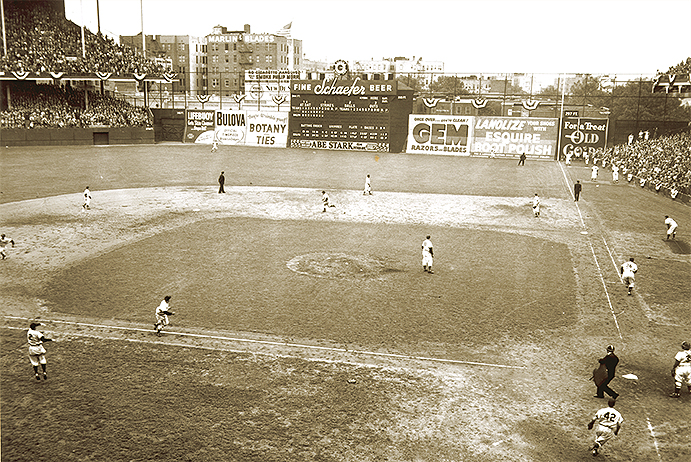

The Yankees and Dodgers traded 1-0 results to begin the Series. A great pitching duel between Allie Reynolds and Don Newcombe in Game One went scoreless into the ninth, but Tommy Henrich—the Yankees’ most revered clutch hitter—resolved matters when he hit a walk-off solo shot. The Dodgers got even in Game Two on an early run scored by Jackie Robinson after he had doubled his way on.

In Game Three at Brooklyn, the Yankees again used late-inning heroics to break open the contest—and the Series—with three runs in the ninth to unlock a 1-1 tie. The Yankees breezed from there, scoring early and often enough at Ebbets Field to repel desperate comebacks by the Dodgers to win Games Four and Five, 6-4 and 10-6.

Off the bench, Johnny Mize ropes a two-run, ninth-inning single to right field at Brooklyn’s Ebbets Field to unlock a 1-1 tie in Game Three and give the Yankees control of a World Series they would win in five. (The Rucker Archive)

Stengel’s method of platooning overcame an anemic offense that batted .226. Joe DiMaggio’s .118 performance reflected his weakened condition as he continued to recover from his late-season illness. Yet the Dodgers hit only .210, and their pitching allowed too many Yankee rallies that made most of New York’s hits count.

Whether he was too old, too unqualified or too much of a buffoon, Casey Stengel weathered the storm of challenges from his critics and his team’s spotlighted injury list. Not only had he commandeered respect for himself, he helped restore a mighty franchise.

The doubters clung to the theory that Casey got lucky. Maybe the bias was starting to show; if so, they were likely to be more infuriated to learn that the New York Yankees’ most dominant era had just begun.

Forward to 1950: Gee Whiz! The Philadelphia Phillies overcome decades of futility and embarrassment with a rare National League pennant.

Forward to 1950: Gee Whiz! The Philadelphia Phillies overcome decades of futility and embarrassment with a rare National League pennant.

Back to 1948: The Greatest Show in Cleveland Bill Veeck, the maverick owner of the Cleveland Indians, brings ’em through the gates with memorable attractions on and off the field.

Back to 1948: The Greatest Show in Cleveland Bill Veeck, the maverick owner of the Cleveland Indians, brings ’em through the gates with memorable attractions on and off the field.

1949 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1949 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

1949 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1949 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

The 1940s: Of Rations and Spoils The return to a healthy economy and the breaking of the color barrier helps baseball reach an explosive new level of popularity—but not before enduring with America the hardship and sacrifice of World War II.

The 1940s: Of Rations and Spoils The return to a healthy economy and the breaking of the color barrier helps baseball reach an explosive new level of popularity—but not before enduring with America the hardship and sacrifice of World War II.

Charlie Silvera discusses what it was like to be a career back-up to Yogi Berra, and on being a New York Yankee during the reign of Casey Stengel.

Charlie Silvera discusses what it was like to be a career back-up to Yogi Berra, and on being a New York Yankee during the reign of Casey Stengel.