THE YEARLY READER

1956: A Perfect Revenge

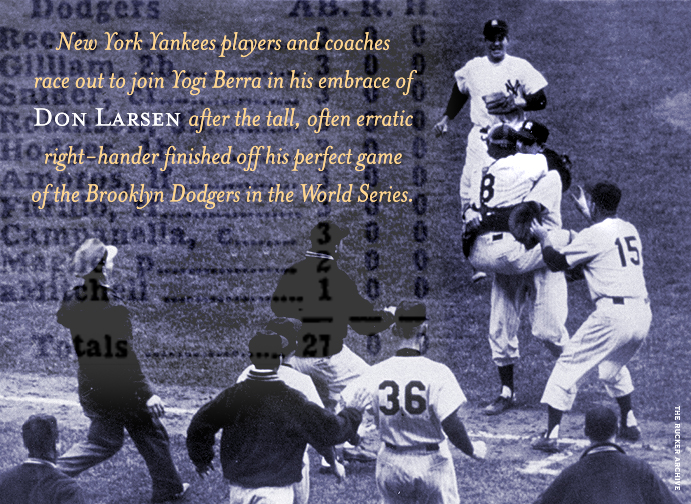

The New York Yankees turn the tables by defeating the Brooklyn Dodgers in another seven-game affair, highlighted by Don Larsen’s perfect game—the first such achievement in 34 years.

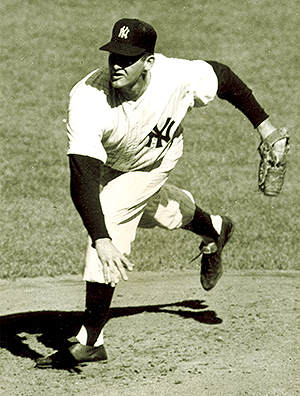

Numerically speaking, Don Larsen was just another common player. In a statistically undistinguished career that spanned from the last days of the St. Louis Browns to the early days of the Houston Astrodome, Larsen won 81 games and lost 91 with six different ballclubs. He never led the league in anything, never got named to the All-Star Game, never had a chance to be enshrined at Cooperstown.

For all of his pedestrian abilities, Larsen earned his fame and fortune in 1956 on a single, beautiful autumn day in New York City, enrapturing the sporting world with a utopian feat even Hall of Famers could only dream of. Larsen’s perfect game—the only one ever thrown during a World Series—was the anchoring moment that helped the New York Yankees completely turn the tables on the Brooklyn Dodgers in a mirror-image rematch of the year before.

A sizeable man at 6’4” and 220 pounds, Larsen began his major league career with the Browns in 1953, turning in a 7-12 record. When the team moved to Baltimore for 1954, the change of scenery only bode Larsen worse luck, his record crashing to 3-21. The Yankees rescued Larsen, who was considered a moderate component of a record-setting 17-player trade between the Yankees and Orioles before the 1955 season. Yet his chronic wildness continued to cost him, and he spent part of 1955 in the minors before being called back to New York for the rest of the year, ultimately winning nine of 11 decisions with a sharp 3.06 earned run average.

While Larsen may have been a common player, he was far a common person—earning a bigger reputation for wildness outside the ballpark than on the mound, one reason he was called “Goony Bird” by Yankees teammates. Mickey Mantle said Larsen was “easily the greatest drinker” he ever knew—an ultimate compliment of sorts from Mantle, who along with fellow Yankees Whitey Ford and Billy Martin were well known for their hardy partying. While at spring training in Florida, Larsen drove his car into a telephone pole in the middle of the night—and manager Casey Stengel defended him in jest by proclaiming, “He oughta get an award, finding something to do in this town after midnight.”

Back on the mound, Larsen played more of a valuable role within the New York starting rotation in 1956. His propensity for walks continued, but batters hit just .206 against him and he finished the year at 11-5, complementing a staff led by Whitey Ford (19-8, an American League-leading 2.47 ERA), 22-year-old Johnny Kucks (18-9, 3.85) and Tom Sturdivant (16-8, 3.30).

At the plate, the Yankees’ lineup—not to mention the rest of the AL—was dominated by Mantle, who in his sixth year finally towered to the Ruthian heights many had expected of him. He exploded out of the gate, hitting .400 well into June, and he became the first player ever to crank out 20 homers before the end of May with spectacular verve—nearly clearing the famous third deck façade at Yankee Stadium with a drive many insisted was still rising when it struck. While Mantle cooled off as the summer heated up, his overall numbers by season’s end easily earned him league-leading numbers in batting average (.353), home runs (52) and runs batted in (130). Playing pain-free for one of the few times in his career helped realize Mantle’s one and only triple crown triumph.

The Yankees took their seventh pennant in eight years with ease, maintaining a healthy lead throughout the summer. The Cleveland Indians once again played second fiddle, but were scarcely a threat as weak hitting could not balance out a trio of 20-game winners in Herb Score, Early Wynn and Bob Lemon.

The Milwaukee Braves, Cleveland’s National League counterparts as perennial silver medalists, made better headway in trying to knock the Dodgers off the championship podium. After a middling start, the high-powered Braves fired manager Charlie Grimm in June and replaced him with Fred Haney—an interesting choice, given Haney’s lifetime 288-526 career record attempting to pilot the Browns and, more recently, the Pittsburgh Pirates. Haney quickly comprehended the concept of a winning attitude as the Braves took their first 11 games under his rule, shooting up the standings from fifth to first place—where they would stay for the bulk of the season.

The Braves were not the only team posing a serious challenge to the Dodgers. Blossoming out of the second division were the Cincinnati Redlegs, featuring a bulked-up offense that smashed a then-NL team-record 221 home runs, making the cozy confines of Crosley Field seem almost claustrophobic. Featured in the cast of non-stop sluggers was 20-year-old Frank Robinson, who with 38 homers equaled a major league rookie record that would stand until Mark McGwire came along 31 years later.

BTW: From 1953 to 1958, the Reds were officially known as the Redlegs, lest anyone should confuse them with communism in the McCarthy era.

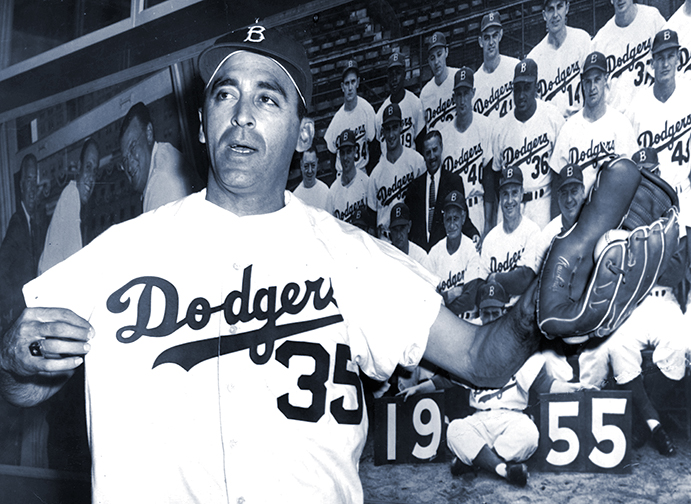

Dealing with this intensified competition was not easy for the defending world champs at Brooklyn. Their potency at the plate, though still effective, continued to diminish with age; it didn’t help that Roy Campanella couldn’t snap his habit of following up feast with famine, as evidenced by a .219 average (with just 20 home runs) after his 1955 MVP campaign. To make up, Dodgers pitching had to step forward and, most impressively because of Don Newcombe and his 27 wins (against just seven losses), it made gains toward that goal.

Yo-Yo Man

Few Hall of Famers have suffered through the ups and downs like Roy Campanella, who wildly careened through a six-year period alternatively filled with MVP-level success and deep, injury-riddled slumping.

To help brush off Milwaukee and Cincinnati, the Dodgers went to the waiver wire and picked up 39-year-old pitcher Sal Maglie. It was a risky move on two fronts: Maglie not only instantly became the oldest Dodger on an already graying roster, he also placed stunned looks on the faces of loyal Brooklyn fans who had learned to hate him after his years knocking down Dodgers as a member of the New York Giants. The cries of wolf in sheep clothing dissipated as Maglie revived a career previously considered over—winning 13, losing five and authoring a solid 2.67 ERA for a Brooklyn team that badly needed such numbers from a starter.

Maglie had his clutch game in prime time for September. In his seven starts that month, the Dodgers won six—losing only a tight affair at Pittsburgh, 2-1. He secured a win over the Braves at Ebbets Field on the 11th, allowing the Dodgers to finally catch up and tie Milwaukee for first place. Two weeks later, while the Braves were eliminating the feisty Redlegs with a win at Cincinnati, Maglie kept the Dodgers alive with a no-hitter against Philadelphia. When the Braves blew their own destiny and lost two of three at St. Louis in the season’s final weekend, it was Maglie leading the final charge for Brooklyn, winning the first game of a doubleheader that launched the Dodgers on a three-game sweep of Pittsburgh and a one-game finish over the Braves for their second straight pennant.

Once hated in Brooklyn, former Giant Sal Maglie signed on with the Dodgers at age 39 and quickly removed the scowls from Ebbets Field fans with a renaissance effort. (The Rucker Archive)

Rewarded for his late-season efforts, Maglie immediately became indoctrinated into the rich World Series rivalry between the Dodgers and Yankees, getting the opening game start in the seventh Fall Classic in 16 years played between the two teams. Maglie’s brilliance continued unabated, going the distance and striking out 10 Yankees in a 6-3 victory.

Don Newcombe, so dominant throughout the year, got the Game Two start—against Don Larsen. As if handed to him on a silver platter, Larsen was the big-time benefactor of a 6-0 lead going into the bottom of the second inning—and he still couldn’t hold it. Goony Bird immediately unraveled, walking four batters in a six-run Dodger second for which he would be given an early exit similar to Newcombe’s. Brooklyn got the best of the Yankees’ bullpen, prevailing 13-8 to take a two-game lead.

New York’s starting pitching strengthened for the next two games at home, as Whitey Ford and Tom Sturdivant helped even the Series with, respectively, 5-3 and 6-2 wins. But those who felt that Yankee pitching had revived itself hadn’t seen anything yet as they walked into Yankee Stadium for Game Five.

Maglie, on four days’ rest, was paired up with Larsen, given only two days to rest up after his brief, disintegrative start in Game Two. Neither pitcher collapsed early on, the two hurlers matching each other out for out into the fourth inning without allowing a single runner.

BTW: Legend has it that Larsen drank hard and late the night before, but Yankee teammates later waived off the tale as pure myth.

Don Larsen was both wild and lousy in his first start of the World Series, allowing four runs on four walks and a hit before being removed in the second inning. His second start was…in a word, perfect. (The Rucker Archive)

To say Larsen held onto the lead was the understatement of the year.

Larsen was sharp to start, gathered emotional steam from inning to inning, and was fairly lucky throughout. He wasn’t giving in, not walking anyone, and even when Brooklyn batters found the sweet swing, they hit ’em where they were—or just foul.

In the second inning, Jackie Robinson hit a sharp grounder that third baseman Andy Carey couldn’t handle—but it deflected right to shortstop Gil McDougald, who threw the speedy Robinson out. In the fifth, Robinson and Sandy Amoros both belted line drives that sailed past the wrong side of the foul pole. Gil Hodges launched one fair, but towards the vast expanses of Yankee Stadium’s left-center field—often referred to as Death Valley—and Mantle made an impressive running catch. In the eighth, Hodges hit a lined shot that Carey plucked just inches off the infield dirt.

BTW: Robinson was playing the third to last game of his career; he would retire following the season.

As Larsen went into the late innings, extending his streak of batters faced and retired from 18 to 21 to 24, he couldn’t help but want to chat about it in the dugout with teammates. Strictly adhering to the long-standing (and still existent) superstition to avoid conversation with a pitcher throwing a no-hitter or perfect game, the other Yankees turned the other way from a hyped-up Larsen.

In the ninth, Larsen dodged a bullet when Carl Furillo flied out on the warning track for the first out. Roy Campanella routinely grounded into the second out, but not before lashing a liner out of play near the foul pole. The 27th batter Larsen would face on the day was pinch-hitter Dale Mitchell. After drawing the count to two balls and two strikes, Mitchell—a .312 lifetime hitter with a great eye who rarely struck out—decided to take a pitch that looked high and away.

Umpire Babe Pinelli threw up the thumb. Strike three.

Larsen’s perfect game was the first in baseball, regular season or postseason, in 34 years. No National League team had been on the losing end of one since 1880.

The perfecto put the Boys of Summer into an immediate autumn funk. Bob Turley shut the Dodgers down through nine innings in Game Six back at Ebbets Field—but fortunately for Brooklyn, Clem Labine stepped away from his regular season role as closer and pitched shutout baseball for 10 innings, the Dodgers finally forcing Game Seven with a run-scoring single by Robinson in the bottom of the 10th. Dodger bats remained asleep in the deciding game and, stunningly, Don Newcombe was again pounded early as the Yankees rolled to a 9-0 win, reclaiming the world championship from Brooklyn.

BTW: Newcombe finished his World Series career with a 0-4 record and 8.59 ERA.

Perfecting a Slump

The Dodgers were adequately hitting the ball around in the 1956 World Series until Don Larsen stepped to the mound for Game Five. Starting with Larsen’s perfect game, Brooklyn bats virtually went into hiding for the rest of the series.

The Series played as a complete inversion of the year before, with the same two teams trading results. The Dodgers, not the Yankees, took the first two games; the Yankees, not the Dodgers, took the next three; the Dodgers, not the Yankees, forced Game Seven; and the Yankees, not the Dodgers, took the rubber match.

This swap of results was pretty much lost on a public that instead absorbed its fascination of a common player who, for one day, made his name one to remember for a long time.

Forward to 1957: If Casey Had a Hammer Hank Aaron ascends to the superstar elite and gives Milwaukee its first World Series title.

Forward to 1957: If Casey Had a Hammer Hank Aaron ascends to the superstar elite and gives Milwaukee its first World Series title.

Back to 1955: Next Year at Last At long last, the Brooklyn Dodgers secure their first—and only—world championship.

Back to 1955: Next Year at Last At long last, the Brooklyn Dodgers secure their first—and only—world championship.

1956 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1956 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

1956 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1956 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

The 1950s: A Monopoly of Success Though described as a golden age for baseball, most major league teams find themselves struggling—unless you’re in New York City, where the Yankees, Dodgers and Giants hog the World Series podium from 1950-56. But as the decade winds to a close, the euphoria of Big Apple baseball will rot overnight.

The 1950s: A Monopoly of Success Though described as a golden age for baseball, most major league teams find themselves struggling—unless you’re in New York City, where the Yankees, Dodgers and Giants hog the World Series podium from 1950-56. But as the decade winds to a close, the euphoria of Big Apple baseball will rot overnight.

Joe DeMaestri serves up true tales of Satchel Paige, Bill Veeck, Paul Richards and the scary side of life in the segregated South.

Joe DeMaestri serves up true tales of Satchel Paige, Bill Veeck, Paul Richards and the scary side of life in the segregated South.