THE YEARLY READER

1985: The Missouri Stakes

The St. Louis Cardinals and Kansas City Royals survive tight pennant races to meet in an intrastate World Series—the fate of which is determined by one of baseball’s most blatant and crucial blown calls.

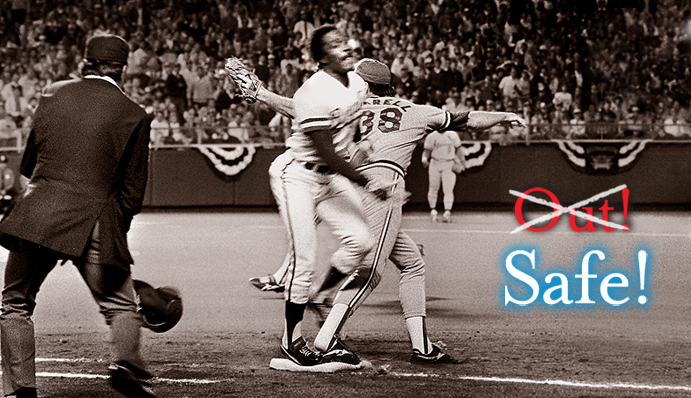

Kansas City’s Jorge Orta reaches first base a half step after St. Louis pitcher Todd Worrell receives a relay throw—but umpire Don Denkinger would call him safe, sharply turning the tide in favor of the Royals in the World Series. (Associated Press)

There is a 10-mile stretch of Interstate 70 in Kansas City named after George Brett, perhaps the most popular man in town ever to wear a baseball uniform—and who in 1985 won the American League’s Most Valuable Player award while igniting the Kansas City Royals to their first World Series championship.

In St. Louis, a 225-mile drive to the east, Cardinals loyalists would have loved to name their portion of I-70 after Whitey Herzog. Or John Tudor. Or Willie McGee. But the harsh fate of the Cardinals’ otherwise superb 1985 season runs cold and deep in the veins of the city’s diehard fans, so the freeway was, years later, named after Mark McGwire, who represented a more pleasing moment in recent St. Louis baseball history.

And if the citizens of St. Louis had the power to do it, they would petition the Missouri state government in Jefferson City to rename the George Brett Super Highway after umpire Don Denkinger.

The bragging rights for 1985’s prize as the best in Missouri—and in baseball as a whole—would be determined through a controversial series of events over the final two games of the World Series, set off by an umpire’s blown call, capitalized upon by a team specializing all year in cardinal comebacks. And that team was not the Cardinals.

The Kansas City Royals entered 1985 with a spate of recent rocky episodes they’d rather had sidestepped from. Since losing the World Series to Philadelphia in 1980, the Royals had reached the postseason twice, both practically by accident: In 1981, as a sub-.500 squad slipping in via the expanded and chastised strike-induced playoff structure; and in 1984, because six other AL West teams couldn’t post a better record than their 84-78 mark. And when four Royals players—including leadoff spark Willie Wilson—were each sentenced to three months in prison early in 1984 for attempting to buy cocaine, some predicted imminent collapse within a typically proud organization.

BTW: Wilson and the other three convicted Royals—Willie Aikens, Jerry Martin and Vida Blue—were each initially suspended for all of 1984 by baseball, but the sentence was cut to the season’s first month.

But the Royals were rescued back to prominence in 1985 thanks to the tandem of Brett and Bret: One a veteran hero who took his game to a whole new level, the other a babyfaced 21-year old catapulting his way to the top echelon of AL pitching.

As George Brett went in the early 1980s, so went the Royals. They rode on Brett’s flirtation with .400 to reach the 1980 World Series, but fell back in ensuing years as the perennial All-Star’s numbers were downgraded from sensational to respectable. Itching to return to superstar form, Brett dedicated himself with an intensified off-season training program for 1985.

Whatever the regimen, it worked. Brett carried the Royals both on offense and defense, smacking a career-high 30 home runs while knocking in 112 runs. Take away his .335 batting average—second highest among AL players—and the Royals’ team average sank to .242, far below any other AL team. At third base, Brett was the lone Royal to win a Gold Glove on defense—his only such award in a 21-year career.

Beyond Brett, strength within the Royals was to be found on the mound with a group of young and talented starters. The steady and dependable five-man rotation—which started all but four games in 1985—was unexpectedly highlighted by a fast-rising sophomore star in Bret Saberhagen.

With innocuous looks that misled an aggressive and clever assortment of pitches, Saberhagen followed up a mundane 1984 rookie campaign with a second-year effort (20-6, a 2.87 earned run average) that would have stolen headlines had it not been for the National League phenomenon known as Dwight Gooden, the virtually untouchable 20-year-old New York Met showing incredible stuff in his second year. But Saberhagen would get his fair share of airtime in the postseason while Gooden sat watching at home.

BTW: Both Gooden and Saberhagen would become the youngest Cy Young Award recipients in their respective leagues.

The Royals trailed the front-running, aging yet ageless California Angels by as much as 7.5 games in midsummer, but Angels manager Gene Mauch never met a lead he didn’t blow. True to form, Mauch could only watch as the Royals whittled away at the Angels and overtook them with an eight-game winning streak to begin September. Never underestimating the value of head-to-head play, the Royals took nine of 13 games from California—including three of four in a crucial late-season series at Kansas City—to help the Royals tip the AL West crown in their favor by a single game over Mauch’s Angels.

Kansas City entered the ALCS as underdogs to the AL East champion Toronto Blue Jays, a young franchise with a young roster that included a trio of exciting 25-year-old outfielders in George Bell, Jesse Barfield and Lloyd Moseby, as well as the AL’s ERA leader in Dave Stieb, at 2.48. The Blue Jays’ 99 wins were all the more impressive considering the top-flight AL East competition—including second-place New York (97-64), sporting a lethal offense that was nevertheless distracted by the continuing—and increasingly tiresome—off-field soap opera featuring owner George Steinbrenner; and the defending world champion Detroit Tigers (84-77), who simply couldn’t revive the magic of 1984.

BTW: Strangely, Dave Stieb could only accrue a 14-13 record despite his top-rate ERA and the explosive Blue Jays offense.

The Blue Jays lived up to their role as ALCS favorites by taking the first two games at Toronto, and they would have made it 3-0 at Kansas City had it not been for a spectacular effort by George Brett, who shouldered the Royals to a 6-5, Game Three win on four hits—including two home runs and a double that missed being a third homer by inches. The Blue Jays bounced back behind Stieb in Game Four to go up three games to one—and in years past, that would have been good enough to send the Jays on to the World Series. But for the first time, both League Championship Series were expanded to a best-of-seven format.

With three to win one, the Blue Jays could not execute.

Early leads held up by stingy pitching gave the Royals three straight victories and their second AL pennant. Echoing the regular season, they couldn’t have done it without Brett, who batted .348—while the rest of the team hit .211.

Across Missouri, the St. Louis Cardinals—much like the Royals—were practically read their last rites before the season even began. They, too, were rebounding from drug scandal, had lost Closer de Jour Bruce Sutter to the Atlanta Braves—and The Sporting News, based in St. Louis, was picking popular Cardinals manager Whitey Herzog as the first to lose his job in 1985.

BTW: After an amazing 45 saves and 1.54 ERA with St. Louis in 1984, Sutter lost it with Atlanta—his ERA ballooned to 4.48—and never got it back.

The preseason storm clouds segued to clear skies for the Cardinals after Opening Day. Already loaded with speed, St. Louis went from fast to fastest with the addition, one week into the season, of outfielder Vince Coleman from the minors. Coleman manufactured a ton of infield hits on the bouncy Busch Stadium Astroturf, and then turned those singles into doubles or triples through an astounding 110 stolen bases on the year. Even without Coleman, the Cardinals were still dashing enough to lead the rest of baseball in steals. Outfielder Willie McGee was second behind Coleman with 56 steals—but that’s not all he did. The 26-year-old switch-hitter led the National League in batting at .353, hits with 218 and triples with 18, part of an impressive array of numbers that earned him the NL MVP.

Two players living unhappy baseball lives within moribund organizations the year before paid major dividends in their first years at St. Louis. Jack Clark fled San Francisco and provided the Cardinals with a rare slugging presence that complemented the team’s singles-and-speed attitude, while being the only right-handed bat in an everyday lineup that included five switch-hitters. And starting pitcher John Tudor, a touchy southpaw exiled from Pittsburgh, overcame a 1-7 start to win 20 of his last 21 decisions (with a 1.34 ERA) to match the ultra-touchy Joaquin Andujar for the team lead with 21 wins, while trailing only Dwight Gooden with an overall 1.93 ERA.

BTW: With 22 home runs, Clark became the first Cardinal to hit 20 or more in a season since 1980.

TAKE THE FAST LANE HOME

Under Whitey Herzog, the Cardinals led the NL in steals over seven straight seasons, from 1982-88. Not surprisingly, Herzog’s speedsters ran away from the competition in stolen bases over the nine full seasons he managed at St. Louis.

Herzog’s resurrected ballclub posted the majors’ best record at 101-61, a remarkable job made necessary as they were tailed closely by the emerging, talented and very cocky New York Mets—led by Gooden, slugging prodigy Darryl Strawberry, All-Star catcher Gary Carter and ex-Cardinal Keith Hernandez.

Also reaching the postseason—for the fifth time in nine years—to meet the Cardinals in the NLCS were the Los Angeles Dodgers, fueled as usual by excellent starting pitching led by Orel Hershiser (19-3, 2.03 ERA) and Fernando Valenzuela (17-10, 2.45). The Dodgers’ hurling worked the Cardinals into an early fix by winning two of the first three games; and then, before Game Four, the Dodgers caught a break—one just below Vince Coleman’s kneecap—after an automatic tarp crept up and rolled over the unsuspecting St. Louis speedster as light rain fell before game time. Coleman—and the Cardinals, it was feared—was done for the year.

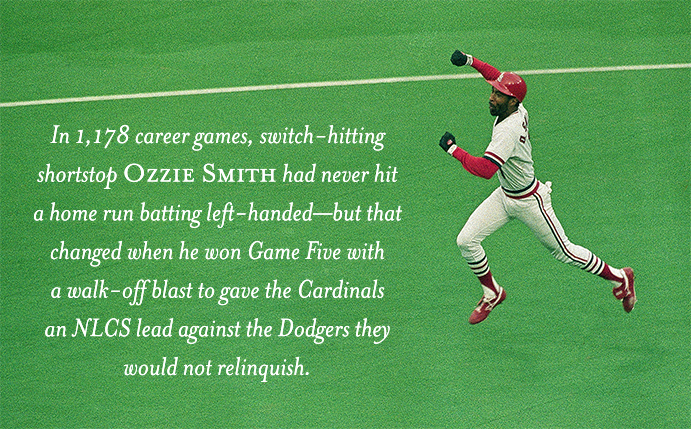

But heroism among the other Cardinals overcame the freak mishap. In Game Five, it was Ozzie Smith—all glove, no hit, definitely no pop—who hit the 14th home run of his eight-year career, and his first ever batting left-handed. It won the game, a walk-off solo shot in the bottom of the ninth that stunned the Dodgers, 3-2.

(Associated Press)

With St. Louis within one win of the pennant, it was Jack Clark’s turn in Game Six. The Cardinals trailed 5-4 at Dodger Stadium in the top of the ninth with two outs and runners at second and third. Rather than bypass the fearsome slugger with an intentional walk, Dodgers reliever Tom Niedenfuer—who served up Ozzie Smith’s rare poke—went after Clark. With a first pitch fastball. Thank you very much, said Clark and his bat, and nearly 400 feet to left field later, the Cardinals had dramatically taken a 7-5 lead that would hold to knock out the Dodgers for the NL flag.

The “I-70 Series”—named as such for the freeway connecting the two World Series participants from Missouri—started well for a Cardinals team riding the euphoric momentum of their NLCS triumph, taking the first two games at Kansas City. Digging out of an early hole yet again, the Royals relied this time on Bret Saberhagen—pitching a complete game six-hitter to win Game Three, 6-1. But the Cardinals won Game Four, and like déjà vu all over again, Kansas City found itself having to win three straight to prevail.

Escaping elimination in St. Louis with a 6-1 Game Five win, the Royals came back to Kansas City hoping to benefit from the presence of the 10th man—their home fans. As far as the Cardinals were concerned, the Royals would also get help from an eleventh: Umpire Don Denkinger.

Behind starter Danny Cox’ stellar performance, St. Louis took a slim 1-0 lead to the bottom of the ninth in Game Six. Three outs were all that separated the Cardinals from their second World Series title in four years. Their bullpen—a collection of equal-time relievers who effectively grouped to offset the loss of Bruce Sutter—hadn’t blown a ninth-inning lead all season. Taking his turn on the mound was Todd Worrell, an intimidating rookie flamethrower who, when last seen in Game Five, faced six Royals—and struck every one of them out.

Veteran Jorge Orta, pinch-hitting to lead off against Worrell, chopped a ground ball left of first base. Jack Clark fielded it and flipped it to Worrell, racing off the mound to cover first. It was a close play, but with Orta a half-step behind Worrell, it didn’t seem close enough to wait for the call from Denkinger. But Denkinger made it as he was paid to do—and ruled Orta safe.

BTW: Video replays proved Denkinger clearly wrong, something the umpire easily admitted upon seeing them.

Denkinger’s incompetence would quickly be matched by that of the Cardinals’. Clark let a pop fly drop in foul territory from the next batter, slugger Steve Balboni—who made Clark pay when he next singled. A passed ball by catcher Darrell Porter moved the two accidental baserunners into scoring position and, a batter later, Duane Iorg knocked them both in with a game-winning—and Series-saving—single.

BTW: Iorg’s previous World Series appearance was as a Cardinal—batting over .500 playing as a designated hitter against Milwaukee in the 1982 World Series.

After falling apart to end Game Six, the Cardinals completely cracked up in Game Seven.

John Tudor started and was uncharacteristically roughed up with five runs in less than three innings—and after being removed decided to take his anger out on an electric fan. The electric fan won; Tudor badly cut up his hand. Two innings, three relievers and six more runs later, Whitey Herzog brought in starter Joaquin Andujar—a puzzling move, given the runaway score, the tense atmosphere and Andujar’s devotion for temper tantrums. Plus, Andujar was sour enough having won just one of his last 10 decisions since capturing his 20th victory back in August.

It didn’t take long for Andujar to erupt. After giving up a single to Frank White, he next faced Jim Sundberg and missed on a pair of two-strike pitches, both of which clearly missed the strike zone and were called as such by—guess who—Don Denkinger. Having just ejected Herzog, Denkinger gave the thumb to Andujar—whose ensuing, manic charge toward the umpire was barely thwarted by Cardinals teammates. “Announcers are always trying to find ways to hold an audience when the score is 10-0,” admitted Al Michaels, doing play-by-play duties for ABC. “The Cardinals have done it for us.”

The St. Louis collapse, whether helped by Denkinger or not, shamefully overshadowed another great comeback performance by the Kansas City Royals. The ever-reliable George Brett hit .370, while Bret Saberhagen enjoyed a most satisfying week in which he was named the series’ MVP with two complete game wins—including a five-hit shutout to win the 11-0 clincher, just a day after his wife gave birth to their first child.

BTW: That the Cardinals came within three outs of winning it all was eye-opening considering that, through the entire series, they couldn’t hit (.185 team average), score (13 runs in seven games) or run (only two steals in five attempts).

Today and every day, Kansas City residents are happily reminded of the Royals’ World Series triumph as they drive along the George Brett Super Highway. And for Cardinals fans passing through town? Well, there’s always old Highway 50 to the south.

Forward to 1986: An October for the Ages A historic postseason full of comebacks and collapses takes on legendary proportions thanks to Bill Buckner.

Forward to 1986: An October for the Ages A historic postseason full of comebacks and collapses takes on legendary proportions thanks to Bill Buckner.

Back to 1984: The Roar of a Powerhouse The Detroit Tigers bolt out to a 35-5 record and coast from their to their first World Series title since 1968.

Back to 1984: The Roar of a Powerhouse The Detroit Tigers bolt out to a 35-5 record and coast from their to their first World Series title since 1968.

1985 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1985 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

1985 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1985 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

The 1980s: Corporate Makeover Baseball enjoys a healthy boom on several fronts, with increased attendance, corporate sponsorship and memorabilia sales; players also continue to enjoy skyrocketing salaries, but some abuse their newfound riches by delving into illegal drugs.

The 1980s: Corporate Makeover Baseball enjoys a healthy boom on several fronts, with increased attendance, corporate sponsorship and memorabilia sales; players also continue to enjoy skyrocketing salaries, but some abuse their newfound riches by delving into illegal drugs.