THE YEARLY READER

1986: An October for the Ages

An unforgettable postseason offers up sensational comebacks, spirited performances and the making of baseball’s most celebrated goat since Fred Merkle in the Boston Red Sox’ Bill Buckner.

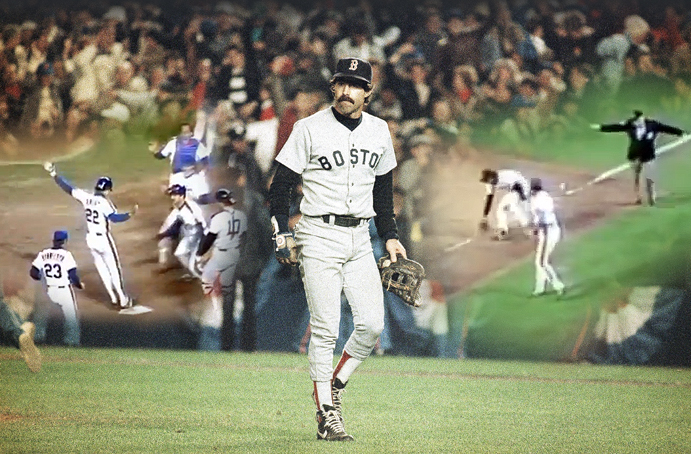

A dejected Bill Buckner leaves the field just moments after committing one of baseball’s most notorious errors; the New York Mets profited and triumphed to finish a wild rollercoaster of a postseason. (Associated Press)

Bill Buckner was a 36-year old with 66-year-old knees. He was still a good enough hitter to play first base every day for the Boston Red Sox, but like a starting pitcher whose arm began to tire, Buckner was typically removed in the late innings to protect his longevity and a Red Sox lead, replaced by his virtual closer in a younger, more defensively agile Dave Stapleton.

Stapleton had relieved Buckner in all seven of Boston’s postseason wins going into Game Six of the World Series against the New York Mets. And with the Red Sox ahead 5-3 going to the bottom of the 10th inning, Stapleton readied to grab his glove and help close it out at first base.

Stay put, said Boston manager John McNamara, who was damned if Buckner wouldn’t get to celebrate on the field. After all, this was history in the making. The Red Sox were three outs away from winning their first World Series since 1918, three outs from ending generations of agony for Bostonian Doubting Thomases, three outs from once and for all exorcising The Curse, cast upon Beantown eons ago when the Red Sox gave Babe Ruth away to the New York Yankees.

History was indeed in the making. But it wasn’t what Buckner and the Red Sox had in mind. Instead, the sensational events of the 10th inning not only reconfirmed the cruel status quo for the Red Sox as baseball’s ongoing Greek tragedy, but also reconfirmed that, just when you thought you’d seen it all in an unbelievable 1986 postseason, you hadn’t.

For all of October’s heroism and infamy, the regular season before it lacked serious suspense as four divisional winners played tough to get all year long. But these four teams certainly provided no shortage of color and excitement, easily making up for non-existent pennant races.

The players:

The New York Mets. Just five years earlier, this was a sorry franchise whose most notable player was fictional: Chico Escuela, the happy-go-lucky, third-rate reincarnation of Ernie Banks as realized by Saturday Night Live’s Garrett Morris. The Mets were rescued from the depths by new owner Nelson Doubleday, Jr. (no relation to alleged baseball inventor Abner Doubleday), who beefed up the front office, opened the vault and astutely rebuilt the Mets with a crafty balance of free agent veterans heavy on leadership (Keith Hernandez, Gary Carter) and can’t-miss blue-chip prospects (Darryl Strawberry, Dwight Gooden). Add in the majors’ youngest and stingiest starting rotation and a cast of colorful supporting players, and the sum total of the 1986 Mets equaled baseball’s answer to the Beastie Boys.

Determined to fight for their right to party, the brash and cocky Mets rubbed their opponents the wrong way—as evidenced by four on-field brawls during the year—but clearly had the look of a team of destiny, winning a club-record 108 games and squelching the NL East to oblivion.

BTW: The defending NL champion St. Louis Cardinals could still run, stealing 262 bases, but getting on base was the problem; they hit .236 as a team. They finished at 79-82.

The Houston Astros. Celebrating their 25th season along with the Mets, many in Houston wondered if it would be their last—as disgruntled owner John McMullen mulled a possible move to Washington in the wake of stagnant support. Nothing brings fans back through the turnstiles faster than winning, and they came roaring back as the Astros thundered through the NL West with their best record to date at 96-66.

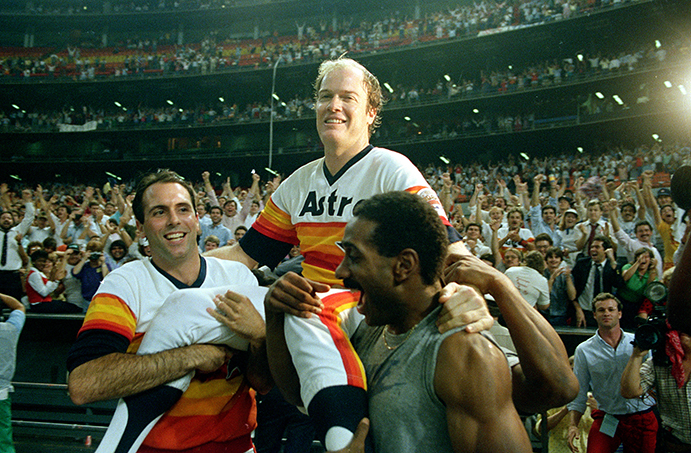

Mirroring the Astros’ rise from recent obscurities was pitcher Mike Scott. Struggling as a pure fastballer through the 1980s, Scott was taught the split-finger—a fastball with the sudden ability to break—from pitching guru Roger Craig, and his career turned instantly around. After winning 18 games in 1985, he won 18 more in 1986—but was far more dominant, doubling his strikeout total to 306 and leading the NL with a 2.22 earned run average. Craig, now the manager for divisional rival San Francisco, knew he had created a monster in Scott; cruelly, the pupil thanked the master on September 25 when Scott no-hit Craig’s Giants to clinch the NL West.

BTW: Craig, who had warned Scott that the split-finger pitch would leave him open to accusations of scuffing, was now himself complaining to umpires about Scott’s possible doctoring of the ball.

To get to the World Series, the Mets would have to get past the Houston Astros and indomitable ace Mike Scott, triumphantly hoisted into the Astrodome air after no-hitting San Francisco to clinch the NL West. (Associated Press)

The Boston Red Sox. As with Scott at Houston, Roger Clemens was the story at Boston—if not all of America. Plagued by arm problems through his first two years, the 23-year-old Texan became an overnight sensation on April 29 when he became the first major leaguer to strike out 20 batters in a nine-inning game. Not afraid to challenge—or even hit—an opposing batter, Clemens intimidated his way to a slam-dunk American League Cy Young (and Most Valuable Player) award performance with a 24-4 record, 2.48 ERA and 238 strikeouts; batters hit just .195 against him.

Clemens’ efforts were aided by a typically potent Boston offense, led by Jim Rice (.324 average, 20 home runs, 110 runs batted in), designated hitter Don Baylor (31 homers, 94 RBIs) and third baseman Wade Boggs, who by hitting .357 captured his third AL batting title in just his fourth full-time year. Bill Buckner, who might had been the DH had they found a capable, healthier hitter to play first base, batted a blasé .267 but did add 18 homers and 102 RBIs.

Boston’s Roger Clemens surges onto the national scene in April at age 23 when he becomes the first pitcher to strike out 20 batters in a nine-inning game; he will go on to win both MVP and Cy Young honors with a 24-4 record. (Associated Press)

The California Angels. As it had been for 10 years, the Angels were loaded with aging postseason warriors of lore. The 1986 roster featured 11 players no younger than 35, including Reggie Jackson (40), pitcher Don Sutton (41), catcher Bob Boone (38) and infielder Bobby Grich (37). Offsetting the elders was the new kid on the block in Wally Joyner, whose 24-year-old face looked 10 years younger. Replacing the retired Rod Carew at first base, Joyner put up the most respectable numbers of any Angel, batting .290 with 22 homers and 90 RBIs.

Barely older than Joyner on the mound were the team’s top two starters, 25-year olds Mike Witt (18-10, 2.84 ERA) and Kirk McCaskill (17-10, 3.36). Backing them up in the bullpen was Donnie Moore, an 11-year veteran and 1985 All-Star who had become the Angels’ star closer—and admirably endured shoulder problems to amass 21 saves with a 2.97 ERA.

Daring to return the Angels to postseason play was manager Gene Mauch, who had twice been so close to the World Series he could have tasted it—only to be force-fed the ashes of his teams’ total collapses. Losing the AL West in 1985 after holding a small lead late didn’t help erase the tag on Mauch as a premier choke artist in the clutch.

BTW: Mauch had retired in 1982 after the Angels blew a 2-0 ALCS lead against Milwaukee, but returned in 1985—replacing John McNamara, who went on to Boston.

THE OVER-THE-HALO GANG

Ten California Angels players, all 35 years of age or older—and all with extensive playoff experience—contributed in varying degrees to the Angels’ successful pursuit of the AL West title in 1986.

The New York Mets’ arrival in Houston to start the NLCS was preceded by their unruly reputation; four Mets players had been arrested earlier in the year for engaging in an off-field brawl at a local country bar. For now, mechanical bulls were not on the Mets’ minds; trying to find a way to beat Mike Scott was.

Scott opened the series by shutting down the Mets, 1-0, on five hits and 14 strikeouts. On three days’ rest, Scott returned to the mound as the Game Four starter and neutered the Mets at New York, allowing just three hits in a 3-1 complete game win. Infuriated as they were frustrated, the Mets were convinced Scott was too good to be true and tried to prove it with a collection of scuffed foul balls they claimed he had thrown. While Scott and the Astros laughed it off, the umpires—who insisted they were watching closely as well—could find no such evidence.

The Mets became resigned that the only way they’d advance to the World Series was to beat everyone else in the Houston rotation—one that included Nolan Ryan (12-8, 3.34 ERA) and Bob Knepper (17-12, 3.14). No suspense would be spared in achieving the mission. They pulled out a come-from-behind win in Game Three thanks to a walk-off, two-run homer from the unlikely bat of second-year outfielder Lenny Dykstra. In Game Four, Dwight Gooden—no longer invincible yet still tough—dueled Ryan into extra innings with a 1-1 tie, broken up in the 12th when a slumping Gary Carter woke up with a game-winning single.

BTW: Nolan Ryan was trying to return to the World Series for the first time since 1969 against the team he had last gotten there with, the Mets.

Back at Houston, the Mets approached Game Six as their Game Seven; losing it would have meant facing Scott in the finale. It didn’t look promising for New York. The Astros jumped on Mets starter Bobby Ojeda (who led the Mets with 18 wins) for three runs in the first inning and made it stick behind Knepper all the way to the ninth. Desperate for the win, the Mets finally broke through with a three-run rally to send it into overtime. It would stay tied all the way to the 16th—even after the teams traded a run in the 14th—when the Mets exploded for three more tallies. Down to their final three outs, the Astros furiously got two runs back and put the tying run on second—but Kevin Bass, perhaps the Astros’ most dangerous all-around hitter, struck out against Jesse Orosco to give the Mets the NL pennant with a 7-6 classic. As the specter of a seventh game against Scott vanished, the sighs in the Mets’ clubhouse were just as audible as the wild cheers.

As with the Mets against Scott, the California Angels fretted over how to beat Roger Clemens as they opened the ALCS at Boston. But unlike Scott, Clemens was far from automatic. He was shelled for every Angels tally in an 8-1 Game One loss; in Game Four, a more deserving Clemens pitched eight shutout innings before he started to fray in the ninth. He was pulled for Calvin Schiraldi, a midseason call-up who had rescued a lost Boston bullpen—but on this day, he could not rescue Clemens. Schiraldi blew the save and allowed the Angels to tie, then doubled his misery in the 11th when he gave up a game-winning RBI single to Bobby Grich.

BTW: Schiraldi saved nine games with a 1.41 ERA in 25 appearances for Boston during the regular season.

Having beaten Clemens twice and leading the ALCS three games to one, Gene Mauch arrived at a situation he had previously lived through twice and suffered nightmares from since. Would his Angels blow the series the way his 1964 Phillies blew the NL pennant, the way his 1982 Angels blew the AL pennant?

For eight innings in Game Five, Mauch believed he had reached the Promised Land. The Angels led 5-2 and were three outs from reaching their first World Series. California starter Mike Witt got two of those outs—but also gave up a two-run homer to former Angel Don Baylor to cut the lead to one. After Mauch brought in reliever Gary Lucas—who hit catcher Rich Gedman with his only pitch—he went to Donnie Moore. The Angels closer had struggled of late, and was only available thanks to a cortisone shot.

Moore’s first batter was outfielder Dave Henderson, who earlier replaced an injured Tony Armas and, in his place, did the Angels a big favor in the sixth when a deep fly by Grich ricocheted off his glove and over the fence for a two-run homer.

After falling behind in the count and then fouling off several pitches to stay alive, Henderson next saw a forkball that never broke.

Henderson slammed it over the fence. Boston, 6-5.

The Angels industriously pulled themselves together and tied it in the ninth, but in extra innings, Moore—left in by Mauch—struggled anew and folded in the 11th when his sudden bane in Henderson hit a bases-loaded sacrifice fly. Moore was finally and mercifully removed, though little mercy was afforded by anything-but-angelic Angels fans who showered him with boos.

Back in Boston, the deflated Angels showed no life despite still having two shots to clinch the AL flag. The Red Sox jumped all over Kirk McCaskill in Game Six, 10-4, and when Boston scored seven runs in the first four innings for Clemens in Game Seven, it was over. The 8-1 victory completed, arguably, the biggest comeback in major league postseason history to date.

Mauch Trial and Errors

For Gene Mauch, the collapse of his 1986 Angels at the ALCS was a nightmare relived. Below is the list of moments in Mauch’s baseball managerial life where his team looked to have it in the bag, until…

Bill Buckner had sprained his Achilles tendon so badly in the ALCS finale, the only way he was going to participate in the World Series against the Mets was to wear special orthopedic high-tops that prompted NBC sportscaster Vin Scully to nickname him “Billy Buckshoes.” Buckner’s condition also made Dave Stapleton’s role as his late-inning reliever all the more critical, and it would be put to good use in the first two games at New York—both won by the Red Sox, 1-0 and 9-3.

The Mets returned the favor in the next two games, playing the triumphant road warriors in beating the Red Sox at Fenway Park, 7-1 and 6-2. Finally, in Game Five, the home team prevailed. The Red Sox’ 4-2 victory put them ahead three games to two as they traveled back to New York—with Clemens ready to start Game Six.

The Rocket went as far as a developing blister would allow, but his effort was adequate enough—leaving with a 3-2 lead after seven innings. Alas for Clemens, Calvin Schiraldi would fail him again. The Mets tied it in the eighth on a Keith Hernandez sacrifice fly and, after a scoreless ninth, Game Six was headed into extra frames.

BTW: Clemens would end up winning only one of his five postseason starts.

Dave Henderson, the Boston super sub and ALCS hero, didn’t waste any time to lead off the 10th; he homered to give Boston the lead while giving himself a serious bid for baseball immortality. One insurance run later, the Red Sox had the Mets backed up against the wall going to the bottom of the frame, leading 5-3.

Schiraldi remained on the mound. Stapleton, against convention, remained in the dugout while Buckner stayed at first base. The first two Mets flied out. The Red Sox sensed the end of The Curse. Destiny seemed abandoned for the Mets. The Shea Stadium scoreboard operator was already conceding, prematurely flashing a message congratulating the Red Sox as world champions. Long-suffering Red Sox fans worldwide began pinching themselves that this couldn’t be true.

It wasn’t.

Gary Carter singled. Kevin Mitchell, undressing in the locker room convinced the Series was over, was told to put his pants back on and pinch-hit. He singled. Third baseman Ray Knight overcame a 0-2 count and singled, scoring Carter and moving Mitchell to third as the tying run.

Veteran Boston reliever Bob Stanley relieved Schiraldi. He engaged Mookie Wilson in a tough at-bat in which Wilson fouled two pitches on a 2-2 count. Then Stanley gave in—unleashing a wild pitch that nearly nailed Wilson’s ankles, bringing Mitchell home with the tying run. The count now full, Wilson swung next and hacked a grounder toward first base. Buckner, playing well behind the bag, watched it bounce once, then twice, then expected a third bounce right in front of his glove.

It skimmed underneath.

Racing around third, Knight deliriously jumped home for joy with the winning run as an incredulous Buckner could only turn around and watch the ball—and the Red Sox’ season—die behind him.

BTW: It’s been said—and widely debated—that even had Buckner fielded the ball cleanly, Wilson would have beat out any throw to Stanley, covering at first; yet Knight would have been held at third.

Game Seven still gave the Red Sox the opportunity to erase the memories of Game Six, but like the Angels before them, the images of agony were too deeply encrypted into the Red Sox’ psyche to make a difference. Even after being spotted an early 3-0 lead by the Mets, the numb and number Red Sox couldn’t hold it. New York tied it in the sixth, and sped past Boston for good in the seventh starting with a Ray Knight home run off Schiraldi—looking more and more petrified as he crashed and burned on the mound once more. The Mets won, 8-5, taking in their second world championship—while the never-ending plight of the Boston Red Sox to win it all grew more Shakespearean.

Bill Buckner, as expected, was hung in effigy by the Red Sox legions for his monumental blunder that put him on the all-time podium of shame with the likes of Fred Merkle and Fred Snodgrass. But Boston fans, while not forgetting, do forgive. After all, heartbreak came with every generation at Fenway Park. Traded in 1987, Buckner returned to Boston in 1990 and was practically hailed as a folk hero. The ribbing of Buckner would remain permanent but good-natured.

Gene Mauch never made it to another postseason. He worked one more year at Anaheim and then gave it up, bowing to health issues. No one has ever managed as long as Mauch and never reached a World Series.

The postscript was more tragic for Donnie Moore. Never forgiven for serving up Dave Henderson’s home run, Moore in the ensuing years fell into physical and emotional disrepair. In 1989, released from baseball, still tormented by the memories of 1986 and in the heat of a domestic spat, Moore shot his wife—who struggled to escape—and then fatally turned the gun on himself.

Had fortune frowned similarly upon him, Dave Henderson likely would have kept the faith. He did all he could to be a hero, but even his performance could only merit a bittersweet denouement. Henderson would soon catch on as a solid, everyday regular in Oakland, displaying a lighthearted joy for the game with his trademarked impenetrable grin. Victory may have eluded him in 1986, but perspective did not. This was, after all, just a game.

And in 1986, baseball fans enjoyed the hell out of it.

Forward to 1987: Dome Sweet Dome The young and feisty Minnesota Twins lose 50 games away from home, but thank God for the Metrodome.

Forward to 1987: Dome Sweet Dome The young and feisty Minnesota Twins lose 50 games away from home, but thank God for the Metrodome.

Back to 1985: The Missouri Stakes Blown calls and hot tempers put a controversial finish to the “I-70 Series” between Kansas City and St. Louis.

Back to 1985: The Missouri Stakes Blown calls and hot tempers put a controversial finish to the “I-70 Series” between Kansas City and St. Louis.

1986 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1986 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

1986 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1986 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

The 1980s: Corporate Makeover Baseball enjoys a healthy boom on several fronts, with increased attendance, corporate sponsorship and memorabilia sales; players also continue to enjoy skyrocketing salaries, but some abuse their newfound riches by delving into illegal drugs.

The 1980s: Corporate Makeover Baseball enjoys a healthy boom on several fronts, with increased attendance, corporate sponsorship and memorabilia sales; players also continue to enjoy skyrocketing salaries, but some abuse their newfound riches by delving into illegal drugs.