THE YEARLY READER

1992: Truly, A World Series

The Toronto Blue Jays become baseball’s first champions outside of America’s borders by giving the Atlanta Braves their second straight World Series setback.

(Associated Press)

Toronto, Canada sits only 30 miles across Lake Ontario from the shores of New York State, but the Toronto Blue Jays were international enough in the eyes of American baseball fans.

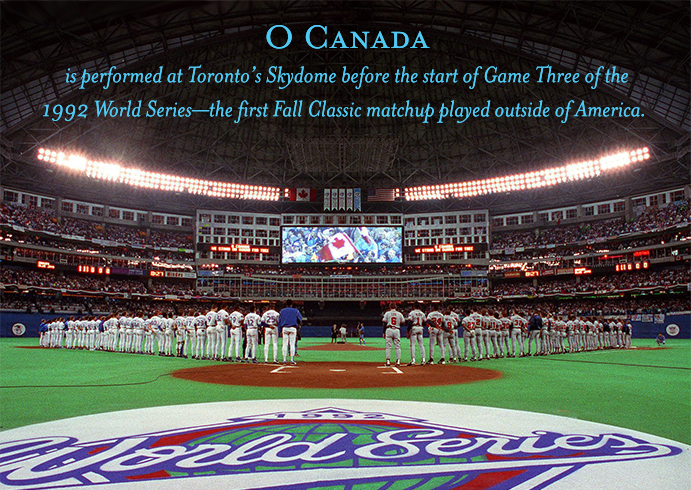

And in 1992, the Blue Jays finally gave relevance to the term World Series.

After finally capturing their first American League pennant, the Blue Jays became the first franchise outside of America’s borders to win the Fall Classic by defeating the Atlanta Braves in a rousing six-game series.

Toronto’s triumph provided a long-overdue moment of bliss for Dave Winfield, 41 and thirsting for his first championship ring after splitting most of his 20 big league years with the fledgling San Diego Padres of the 1970s and the dysfunctional New York Yankees circus of the 1980s. Winfield, whose brief and dismal October experiences got him labeled “Mr. May” by Yankees owner George Steinbrenner—who never gave him a chance to relax in New York—got the last laugh as he connected on a game- and series-winning double in the 11th inning of Game Six, scoring two runs to give the Jays a 4-3 victory at Atlanta. The resulting celebration back in Toronto was one that, not long ago, could have only been reserved for hockey’s Maple Leafs.

The Blue Jays’ triumph was their first after many discouraging close calls over the past decade. Struggling exclusively in the AL East basement from their 1977 inception through 1982, the Blue Jays discovered a different kind of woe between 1984-91 when they were denied entry into the World Series thrice—bowing in the ALCS—and finishing second in the AL East another three times. Nevertheless, since leaving last place in 1982, they were competitive enough never to finish worse than 86-76 in any one season.

Winfield, once reviled in Canada for (accidentally) killing a seagull with a warm-up throw in Toronto while playing for the Yankees, was forgiven by the Blue Jays fan base and thrived on the more relaxed spirit that absorbed him with a renaissance campaign, hitting .290 with 26 home runs and 108 runs batted in. His performance was all the more impressive considering the extensive back injury that kept him out of the entire 1989 season with the Yankees.

Also providing a mercenary angle for the Blue Jays was pitcher Jack Morris, who the year before had signed on with the Minnesota Twins, his hometown team. Morris expressed at that time how wonderful it was to be back home—then promptly led the Twins to the World Series championship, memorably pitching a 10-inning shutout in Game Seven that made him the toast of the town. Despite that storybook success, Morris suddenly switched gears and signed on with Toronto for 1992—embittering Twins fans and management alike. In the meantime, Blue Jays fans could care less about Morris’ long-term plans; the 37-year-old right-hander, in spite of a pedestrian 4.04 earned run average, was effective enough to win 21 and lose only six in 1992.

BTW: Morris publicly theorized that the late arrival of his World Series ring—long after the other Twins players of 1991 received theirs—had everything to do with his sudden exit from Minnesota.

Late Blue Jay Malaise

Until conquering the World Series in 1992, the Blue Jays suffered through a decade’s worth of late-season frustration in which division leads and playoff series were lost when all seemed won, as shown below.

For the second straight year, the Atlanta Braves would lose the World Series on their opponent’s last at-bat. But in getting to the Series, Atlanta tasted the winning side of such theatrics.

Pitted once again with the Pittsburgh Pirates in the NLCS, the Braves appeared to be looking down and out as they approached the bottom of the ninth inning of Game Seven in Atlanta. Trailing 2-0 and facing Pirates ace Doug Drabek, the Braves loaded the bases with no one out—thanks to a double, a rare error by Pirates second baseman Jose Lind and an intentional walk. A fatigued Drabek was replaced by reliever Stan Belinda, who allowed one run on a sacrifice—but got two outs in the meantime.

Francisco Cabrera then stepped to the plate.

The Braves rested their season’s hopes on a 26-year old with all of eleven regular season plate appearances to vouch for. But Cabrera responded to the challenge by lining a 2-1 pitch into left field, easily scoring Dave Justice from third to tie; the ball’s placement in the outfield was also good enough to get slow-footed Sid Bream to chug home from second, barely beating out Barry Bonds’ throw. The Braves were 3-2 winners and National League champions for the second year in a row. The sellout crowd at Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium went nuts, and Cabrera became an instant legend for Braves fans to remember.

Atlanta’s Sid Bream celebrates his pennant-winning charge from second base against Pittsburgh to put the Braves in the World Series for the second straight year. (Associated Press)

The Braves earlier had less trouble capturing their second straight NL West crown. Impressive starting pitching once again provided the Braves with their most potent weapon; Charlie Leibrandt (15-7) had the worst of their starters’ ERA—at 3.36. Tom Glavine was the team’s main ace, winning 20 for the second straight year while losing only eight with a 2.76 ERA. At the plate, Terry Pendleton proved that his vastly improved 1991 campaign was no fluke, again leading the offense with a performance (.311 average, 21 homers and 105 RBIs) that compared well with his Most Valuable Player numbers of the year before.

As the Braves would experience the sting of defeat in the World Series, so would the Pirates in the NLCS—but for the third straight year. Denial to the 1992 Series would be an especially bitter pill for Pirates fans to swallow. They were convinced free agency would take Barry Bonds and Doug Drabek out of Pittsburgh uniforms, and that 1992 would be the last big chance—for a while—to see their team take it all. Sure enough, the painful exit out of the playoffs would end the Pirate careers of Bonds (the National League MVP), Drabek and Jose Lind, all opting to sign big new contracts with the Giants, Astros and Royals, respectively—and set the Bucs on an unprecedented run of failure in the standings.

Getting to the playoffs posed little problem for the Pirates, who despite a late rush from a young, aggressive Montreal squad wound up the season with an eight-game lead—the biggest margin of any division.

Oakland manager Tony La Russa did wonders in taking an aging, sometimes battered A’s team to the AL West title, rebounding from a frustrating off-year in 1991. Leading the way was closer Dennis Eckersley, who had the most influential of all his great years slamming the door on opponents for the A’s. The 37-year old saved 51 games, won another seven and put forth a 1.91 ERA—a combined set of numbers that earned him the AL’s MVP award. His efforts were shared with a comeback showing by Mark McGwire, overcoming on- and off-field problems in 1991 to clout 42 home runs—second only to the 43 belted out by young Juan Gonzalez of the Texas Rangers. Playoff experience among the veterans—this was Oakland’s fourth ride to the ALCS in five years—was crucial in knocking off defending World Series champion Minnesota, who finished six games back.

Alas for Oakland, the Toronto Blue Jays proved too overpowering in the ALCS. The A’s shouldered their hopes too heavily on Eckersley, and it ended up costing them by Game Four. Eck’s extended, exhausting relief appearance that day helped the Blue Jays erase a 6-1 deficit and win in 11 innings, 7-6. It turned the tides of fortune Toronto’s way, as the Jays went on to grab the AL pennant in six games.

In spite of the Blue Jays’ dominance, they had the toughest time of all the division winners securing first place. The Milwaukee Brewers, under first-year manager Phil Garner, used an aggressive baserunning strategy—they stole 256 bases, 100 more than the next best team—and rode on an AL team-best 3.43 ERA to finish within four games of Toronto. Like the Pirates, the Brewers would go on a prolonged run of losing that would last well into the next century’s first decade. Misery, after all, likes company.

A painful series of developments regarding the commissioner’s office—or the lack thereof—left many baseball fans shaking their heads in disgust. Ever since baseball owners gave Kenesaw Mountain Landis the throne as baseball’s first commissioner in 1920, it was understood that the job description included making critical judgments in the best interests of baseball, not necessarily those of the owners. But there was a rising tide of dissatisfaction against current commissioner Fay Vincent from the Lords of Baseball, as rumors began to swell that the owners would pull a power play to reduce Vincent’s authority—if not to outright remove him.

The most celebrated of the thorny issues facing Vincent was that of NL divisional realignment. Vincent wanted Cincinnati and Atlanta to switch divisions with Chicago and St. Louis, saying it was a more sensible geographic arrangement, and believed he had the unilateral authority to impose it on the owners. Threatened with legal action and facing increased opposition fostered by the Tribune Company, which not only owned the Cubs but the TV “superstation” (WGN) that carried their games—many of which would likely go well into the Midwestern night if the Cubs relocated to a division loaded with West Coast teams—Vincent backed down.

Already having made a few enemies with his role in resolving the Spring 1990 player lockout—the ending of which, many owners believed, favored the players—and his more recent, heavy-handed dealing of New York Yankees players, coaches and management over the latest Steve Howe drug-related suspension, the coals began to burn too hot under Vincent’s chair. The owners were angered enough that, by Labor Day, they gave him a vote of no confidence. An initially defiant Vincent realized he’d have to sue to keep his job; but instead he evoked “the best interests of baseball” and quit on September 8, knowing that an ugly, highly publicized battle in the courts would be harmful to the game’s image.

To no one’s surprise, the search for Vincent’s replacement seemed non-existent. For now, the commissioner’s office was being rented on an “interim” basis by one of the owners’ own, Milwaukee’s Bud Selig. A new TV contract needed to be worked out—with certainly less revenue expected—and potentially bitter labor negotiations were lurking on the horizon. The last thing the owners wanted was “interference” to keep from weathering these storms out to their advantage.

The authority of the commissioner had eroded from the virtual dictatorship of Landis, 70 years earlier, to almost nothing, back in the hands of those who preceded the concept: The owners. With the removal of a true, independent commissioner came the alarming disappearance of a healthy checks-and-balance system that had saved the game and given it more health. Selig would eventually assume the commissioner’s throne on a permanent basis and help initiate, without question, Major League Baseball’s most prosperous period of financial growth. But this transition to a more lucrative existence brought with it a change in priorities. The “best interests of baseball” were no longer about the sanctity of the sport; they were, instead, about its profit motives.

For now, what made the new ruling roundtable of owners more frightening was that they couldn’t even seem to agree with each other; the Vincent affair was not entirely unanimous, and it created varying rifts. Regardless, it was the owners’ act now; the next few years would clearly show that out.

For the National Pastime, it would be the beginning of a very rocky road.

Forward to 1993: The Last Great Pennant Race On the eve of the wild card era, 100-game winners San Francisco and Atlanta fight it out for a single postseason spot.

Forward to 1993: The Last Great Pennant Race On the eve of the wild card era, 100-game winners San Francisco and Atlanta fight it out for a single postseason spot.

Back to 1991: From Worst to First Out of nowhere, the Minnesota Twins and Atlanta Braves leap to the top and put on one of the most memorable World Series.

Back to 1991: From Worst to First Out of nowhere, the Minnesota Twins and Atlanta Braves leap to the top and put on one of the most memorable World Series.

1992 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1992 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

1992 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1992 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

The 1990s: To Hell and Back Relations between players and owners continue to deteriorate, bottoming out with a devastating mid-decade strike—souring relations with fans who, in some cases, turn their backs on the game for good. Recovery is made possible thanks to a series of popular record-breaking achievements by ‘class act’ stars.

The 1990s: To Hell and Back Relations between players and owners continue to deteriorate, bottoming out with a devastating mid-decade strike—souring relations with fans who, in some cases, turn their backs on the game for good. Recovery is made possible thanks to a series of popular record-breaking achievements by ‘class act’ stars.