THE YEARLY READER

1995: Thanks to Cal, Hideo—and Sonia, Too

Its player strike finally settled, baseball faces a monumental task to bring back the fans—and makes solid headway with the record-breaking performance of Cal Ripken Jr., Hideo Nomo’s sensational debut and the Cleveland Indians’ first pennant in over 40 years.

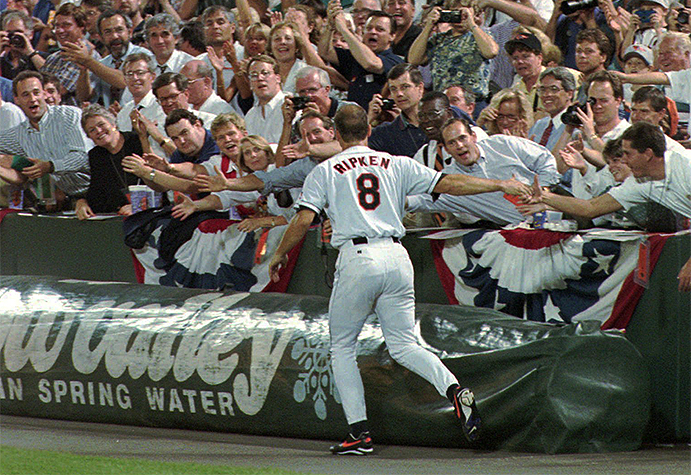

Cal Ripken Jr. takes a victory lap in the middle of his 2,131st consecutive appearance to break Lou Gehrig’s iconic record; it was the high point in a post-strike campaign in desperate need of positive vibes. (Associated Press)

When baseball loyalists awoke from their winter hibernation in the spring of 1995, they wondered if all they had remembered from 1994 was nothing more than a long nightmare.

It was no nightmare.

Worse, it was still happening.

While the fans were sleeping, negotiators for major league owners and players were wide awake, still trying to hammer out a new labor agreement and end the strike that killed the 1994 major league season—and now threatened the 1995 schedule. Yet zilch progress was made, even after the owners softened their stance on a salary cap in the form of a luxury tax, designed to transfer revenue from teams with the highest payroll to those with the lowest. More sobering was that both sides remained as contentious as ever. The incivility reached a low point when Chicago White Sox owner Jerry Reinsdorf—a militant salary cap proponent accused by some of pulling puppet strings over interim commissioner Bud Selig—compared union boss Don Fehr to Jonestown cult leader/mass murderer Jim Jones.

Not even President Bill Clinton, opening up his Cabinet and pulling out Secretary of Labor Robert Reich to get hands-on in the negotiations, could get either side to budge.

As Florida and Arizona began warming up for spring training, the owners—having declared an impasse and unilaterally imposing their own conditions, salary cap and all—were determined to get the 1995 season in with or without the striking players. So they called in the replacements—or, as defined by unionspeak, the scabs.

Made up of minor leaguers, amateurs and aging former big leaguers, the replacements received $628 a day and generated reaction from curiosity to scorn from the very few who showed up to spring training games. The landscape of an upcoming replacement regular season was peppered with landmines. Baltimore owner Peter Angelos refused to use replacements, insisting that no game involving his Orioles would go on without a striking Cal Ripken Jr.—closing in on Lou Gehrig’s mark for consecutive games played. Sparky Anderson, a player’s manager, refused to lead Detroit replacement players and was obliged with a leave of absence by Tigers management. And Dunedin, Florida readied to be the regular season home of the imitation Toronto Blue Jays, as Ontario law forbid strikebreakers from being used within its borders. The Jays’ replacement ballpark, with 45,000 less seats than Skydome, was not considered a threat to sell out.

BTW: Among those attempting a comeback amid the younger replacements were Oil Can Boyd, Guillermo Hernandez and 48-year-old Pedro Borbon.

Bet You Won’t See This On MLB.com

Since 1969, when the first weeks of spring training were interrupted with a partial player strike over pension amounts, baseball has endured through nine work stoppages—the most recent of which was its most crippling, wiping out parts of two seasons and the 1994 postseason.

With prospects for a 1995 season using “real” players looking bleak and no progress being made at the bargaining table as the two sides sniped at each other as intensely as ever, the madness made of male baseball millionaires and multi-millionaires over eight months would finally be brought to its knees…by a woman.

On March 31, in response to a National Labor Relations Board charge of unfair labor practices by the owners, U.S. District Judge (and future Supreme Court justice) Sonia Sotomayor heard both sides speak their mind. Then she spoke hers: Return to the old bargaining agreement until a new one could be reached. Unlike all previous third-party interests involved with the strike—from fans to mediators to the President—Sotomayor’s edict carried legal weight. Elated, the players agreed to return to work, while the owners—stripped of their ace card—now threatened a lockout. But faced with millions of dollars in potential fines if they defied Sotomayor’s order and let the replacements play on—something resembling the New York Mets and Florida Marlins were in uniform and hours away from playing the replacement season opener in Miami—they had no choice but to fold.

BTW: The owners filed an appeal to Sotomayor’s ruling, but the U.S. Court of Appeals told them, in effect, to get lost.

Thus, baseball was back on.

A belated, shortened spring training period for the returning players was followed by a reduced 144-game regular season schedule. But at least it would be played—as would the World Series, after a forced one-year layoff.

Opening Day 1995 arrived on April 25—and the fans, who had nothing to say for eight months, were ready to let baseball have it.

The Atlanta Braves, who before the strike averaged 40,000 per game, drew only 24,000 for their home opener. In their second home game, Atlanta starting pitcher Tom Glavine—the team’s union representative—was unmercifully booed by his own fans. Same thing for Pittsburgh rep Jay Bell at the Pirates’ home opener; when the Bucs started booting the ball around in the fifth inning, disgruntled fans threw sticks they had torn from freebie pennants and littered the field, causing a 17-minute delay. In Kansas City, a Royals hitter fouled a ball into the seats. A young fan caught it and threw it back on the field, to the elated cheers of the crowd. And a group of fans invaded the Shea Stadium infield in New York and tossed dollar bills at Mets players. Bret Saberhagen, pitching on the mound for the Mets, said he would have picked the money up had they been $100 bills.

When only 31,000 showed up for Milwaukee’s home opener, Brewers owner and interim commissioner Bud Selig blamed wintry 40-degree temperatures. What he didn’t acknowledge was that the previous season’s home opener was played before a sellout crowd in weather 10 degrees colder.

If the fans’ hatred was enough to scare the owners and players, then their indifference—best reflected in a whopping 20% per-game drop in 1994 attendance—was far more frightening. At least those expressing their vitriol at the ballparks were showing up. Had they lost the others for good? And what could possibly bring them back?

Ode to the Empty Seat

Fans were slow to return back to major league ballparks following the 1994-95 players strike. Only three teams—Boston, California and Cleveland—improved on their per-game average over 1994, the latter two just barely. The other 25 franchises posted significant drops; below are the 10 that suffered the most.

Rising high above baseball’s ambitious multimedia marketing campaign to win the fans back were a couple of inspiring, individual stories that connected with and captivated the nation.

From 1990-93, Hideo Nomo led Japan’s Pacific League in wins and strikeouts. He suffered shoulder problems in 1994 and was unsatisfied with the latest contract offer by his team, the Kintetsu Buffaloes. So he decided to try America, where only one other Japanese player—Masanori Murakami, from 1964-65—had previously played in the majors.

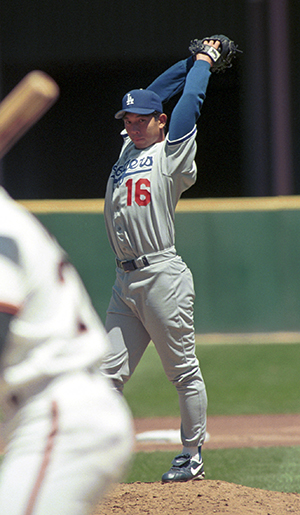

The majors’ second Japanese player—and the first in 30 years—Hideo Nomo achieved instant stardom in Los Angeles with his unusual pitching style and overall effectiveness; his success finally opened the floodgates for ballplayers from the Orient. (Associated Press)

Signed by the Los Angeles Dodgers for a miniscule $109,000 salary dwarfed by a $2 million signing bonus, Nomo was winless in his first six major league starts, dogged by wildness that frequently got him in trouble. In his seventh start, Nomo found his control and locked in through the summer, going 9-2 over his next 13 starts with 119 strikeouts and just 50 hits allowed in 103.1 innings.

There was more to the modest, 26-year-old Nomo than just success and international appeal; his pitching delivery was one of the most unusual in modern times, a tornado-like windup in which he raised his arms high and spun slowly to a stop with his back completely facing the batter, before twisting back and firing away. Nomo’s sudden stardom made him the Dodgers’ second foreign pitching sensation in 13 years (following Mexico native Fernando Valenzuela in 1981), earned him a start at the All-Star Game (where he pitched two scoreless innings for the National League) and received the ultimate status of the day, as a poster boy for Nike.

Nomo’s star lost some of its luster late in the year as his pitching became erratic, but his 13-6 record and NL-high 236 strikeouts were just enough to send the Dodgers over the top to win the NL West by a game. His memorable debut was also just the tonic baseball needed to revive its rock-bottom image.

The game would be the benefactor of more public relations goodwill—not by an overseas savior, but a blue-eyed, blonde-haired hero about as home-grown as it got.

Cal Ripken Jr. had not missed a game for the Baltimore Orioles since May 29, 1982. Much had happened since in Baltimore: A world championship, a 21-game losing streak, hundreds of roster moves, seven managerial changes and a new ballpark. But one thing remained constant: The everyday appearance of Ripken, the perennial All-Star shortstop and all-around good guy. And now, the 35-year-old Ripken—his hair graying and thinning, but athletically still quite durable—was within tantalizing reach of one of baseball’s most hallowed and seemingly unbreakable records: Lou Gehrig’s consecutive game mark of 2,130.

Unlike with most records, Ripken’s scheduled 2,131st straight appearance had a fixed date: September 6 at home against the California Angels. Orioles baseball in general was already a hot ticket since Oriole Park at Camden Yards opened, so one could only imagine the bribes being offered to ticket holders for Ripken’s record-breaker.

BTW: Pundits such as talk show host Larry King and the New York Times’ Robert Lipsyte ludicrously argued that Ripken should sit down after 2,130 games and let Gehrig keep a share of the record.

Ripken would not disappoint those who shelled out major bucks to watch him achieve one of baseball’s ultimate milestones. He had already homered the night before as a thank you for those who came to watch him tie Gehrig’s mark, and in the fourth inning of game number 2,131, he went deep again. But the real fun began a half-inning later, in the middle of the fifth. It was at that moment, when the game was declared official, that Ripken’s passing of Gehrig was secured.

As giant, single-digit banners were unfurled to spell “2131” on the old B&O warehouse behind Oriole Park’s right-field bleachers, the game was stopped and Ripken, prodded by his teammates, took a lap around the field, receiving high fives from anyone he was able to get close to—the fans, field employees, and players from both teams. At 22 minutes, it was a work stoppage fans were happy to experience; among those in the crowd were Bud Selig and Don Fehr, two gentlemen who saw first-hand a desperately needed feel-good event in a game they had nearly destroyed.

For the sake of baseball’s future, here was hoping that the emotion of the moment would be forever etched upon their souls.

The majors’ slightly shortened season made for a jumble of deluded pennant and wild card races in baseball’s brave new world of split divisions and expanded playoff participants. But when all was said and done and the contenders had spoken, righteousness prevailed as the teams with the two best records made it through to the World Series.

(Associated Press)

A year earlier, the Cleveland Indians had begun to flex their muscles after four decades of dormancy, making a serious bid for a postseason that never happened. The abandoned 1994 season would be more than a fleeting chance for the Indians; they were, in fact, warming up for 1995.

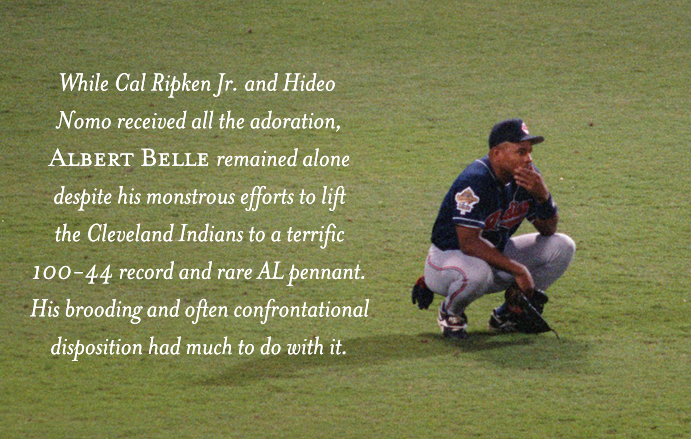

The Tribe’s 100-44 record was the best put forward by a major league team since…the 1954 Indians, who finished 111-43. The Indians played superior clutch baseball by winning 25 games in their last at-bat, and showed dominance by leading the American League in all things offensive—from batting average to home runs to stolen bases to Albert Belle tantrums to ethnic caricatures (the Chief Wahoo icon, increasingly derided by Native American groups). They had six everyday players hitting over .300—one of which was the irascible Belle, who played as angrily as he seemed to live, leading the AL with 50 homers, 52 doubles, 121 runs scored and 126 knocked in. Cleveland pitching fielded the league’s best earned run average (at 3.83) and featured a tremendous 1-2 bullpen duo with set-up artist Julian Tavarez (10-2, 2.44 ERA) and closer Jose Mesa (46 saves in 48 opportunities and a terrific 1.13 ERA).

BTW: The Indians finished a record 30 games ahead of second-place Kansas City, although in the old two-team AL format, they would have placed 14 games over New York.

The Indians took the newly-required extra mile to the World Series, first dismissing the AL East-winning Boston Red Sox in three straight in the first-round Division Series (ALDS), then cooling off the red-hot Seattle Mariners—who overcame a late 13-game deficit to win their first-ever AL West title—in a taut six-game ALCS.

BTW: The Red Sox’ two big boppers, Jose Canseco and AL MVP Mo Vaughn, combined to go 0-for-27 against Cleveland.

Rightfully hooking up with the Indians at the World Series were the Atlanta Braves, who breezed through their two rounds of NL playoff competition. The team’s offense, a youthful and balanced group with adequate punch—in spite of the majors’ third worst batting average at .250—awoke and hit .331 in its first-round, three-games-to-one triumph over NL wild card entry Colorado. But at the NLCS, it was Atlanta pitching—once again the core of the Braves’ overall success—that completely silenced NL Central champion Cincinnati, which scored only five runs and hit .209 in a four-game Atlanta sweep.

Greg Maddux remained the star of stars in the Braves’ vaunted rotation. Clearly in his prime, the 29-year-old right-hander won 19, lost just twice, and produced a sizzling 1.63 ERA that ran counter to baseball’s emerging era of bloated offense. Maddux’s 23 walks over 210 innings was apt tribute to his pinpoint accuracy.

Baseball reclaimed the October stage it abandoned the year before, and although the players were asked to bend over backwards to try and win the fans back, some at the World Series apparently didn’t get the memo. Albert Belle, for one, was in top form before Game Three when, for no particular reason, he decided to chase NBC sideline reporter Hannah Storm out of the Indians’ dugout with a profanity-laced tirade. And before Game Six—with the Braves at home leading, three games to two—Atlanta outfielder David Justice blasted his own fans as being unsupportive and overcritical, adding that they might “try to burn our houses down” if the Braves failed to win.

BTW: Belle later apologized, but was walloped with a $50,000 fine—the largest in major league history.

Promptly booed in pre-game introductions, Justice made amends and went from villain to hero in Game Six with a sixth-inning solo home run that became the game’s only tally. Making it stand up was Tom Glavine—the other post-strike target of Atlanta fans—who allowed but a bloop single over eight impeccably pitched innings before Mark Wohlers closed out the Indians—and the 1995 season—in the ninth.

The Braves’ first championship in 38 years—and their first in Atlanta—would be their one and only triumph within an extended run of success under manager Bobby Cox that began in 1991 and continued into the 21st Century. They would discover with cold reality that, in baseball’s new frontier of wild cards and multiple playoff rounds, being the best team over 162 games—or 144, in the case of 1995—doesn’t get you as far as it used to.

Forward to 1996: Here’s at Spittin’ at You, Kid Roberto Alomar takes center stage in the worst way, only to have it stolen by a Jersey kid in a classic case of poetic justice.

Forward to 1996: Here’s at Spittin’ at You, Kid Roberto Alomar takes center stage in the worst way, only to have it stolen by a Jersey kid in a classic case of poetic justice.

Back to 1994: The Year That Should’ve Been Record-breaking quests, unlikely team revivals and an entire postseason are done in by a devastating player strike.

Back to 1994: The Year That Should’ve Been Record-breaking quests, unlikely team revivals and an entire postseason are done in by a devastating player strike.

1995 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1995 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

1995 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1995 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

The 1990s: To Hell and Back Relations between players and owners continue to deteriorate, bottoming out with a devastating mid-decade strike—souring relations with fans who, in some cases, turn their backs on the game for good. Recovery is made possible thanks to a series of popular record-breaking achievements by ‘class act’ stars.

The 1990s: To Hell and Back Relations between players and owners continue to deteriorate, bottoming out with a devastating mid-decade strike—souring relations with fans who, in some cases, turn their backs on the game for good. Recovery is made possible thanks to a series of popular record-breaking achievements by ‘class act’ stars.