The Ballparks

Busch Memorial Stadium

St. Louis, Missouri

(Jerry Reuss)

Yes, Busch Memorial Stadium was a “cookie cutter” venue, but a good one—and one that aged fairly well once the Cardinals ripped out an artificial turf you could fry eggs on and planted natural grass beholding unnatural sluggers, cheered on by a loyal red-clad fan base whose enthusiasm was as strong as the 96 arches that topped the stadium were graceful. After years of rickety Sportsman’s Park, Busch Memorial provided a gateway to modern times in St. Louis.

They came from far and near, seduced by the vocal inflections of Harry Caray and Jack Buck via a powerful KMOX radio signal that painted the Midwest red. They were the rabid fans of the St. Louis Cardinals, and for 40 years they came and kept coming to the shrine of their beloved, at Busch Memorial Stadium—a modern coliseum of class whose reputation as just another multi-purpose concrete donut was predictably but unfairly lumped with other such stadia of the times, imitators that lacked Busch’s proud touches of civic reflection and baseball heritage.

In between Busch Stadium and Busch Stadium, there was Busch Memorial Stadium, which bridged the rustic early days of Branch Rickey, Dizzy Dean and Stan Musial to the new millennium of Tony La Russa, Albert Pujols and Yadier Molina. Busch Memorial’s lifespan could be broken down into three acts: The early years where Bob Gibson terrorized opponents from the mound and Lou Brock stole the hearts of Cardinals fans along with all those bases; the middle years, where speed, defense and line drives atop a fast, sweltering artificial turf became the Redbirds’ M.O.; and the final years, when the venue truly looked more like a ballpark and became an unlikely setting for home run records to fall.

While the Gateway Arch, built simultaneously, would become St. Louis’ signature symbol amid a massive redevelopment project south of downtown, Busch Memorial Stadium would be the true beacon that kept the city financially alive, generating untold millions in revenue through nearby restaurants, retail shops and hotels.

Arching Toward the Future.

If any city was in need of a jolt of progress, it was postwar St. Louis. Like many other rust belt metropolises, the Mound City looked to be dying before everybody’s eyes in the 1950s. The middle class fled to the suburbs as new development was next to nil; not a single private office building had been erected in town for three decades. Several major magazines of the day, from Fortune to The Saturday Evening Post, took shots at St. Louis for its increased blight and decay. Something needed to be done. And fast.

Charles Ferris saw the future of St. Louis and was in a position of power to see it through to reality. A towering presence full of confidence, Ferris became the city’s head of development and set about overhauling a 31-block section south of downtown that represented the worst of the widespread blight. Ferris knew that it was just a matter of time before the adjacent Gateway Arch—designed in 1947 by famed architect Eero Saarinen, but yet to be built due to various funding and right-of-way issues—would finally be erected; more importantly, he knew that the emergence of four converging interstate freeways in the immediate area could spark easy access from points near and far to newly built attractions in the redevelopment area. But what would be the attractions? More office buildings?

Sportsman’s Park, renamed Busch Stadium when Budweiser king August “Gussie” Busch Jr. bought the Cardinals in 1953, might have been perfect circa 1920 when the average fan rode the streetcar there, but it had become badly outdated with no public parking to accommodate the meteoric postwar rise in individual auto ownership. Moreover, it was just old. Ferris was looking for something new. The locals were not going to come see the Gateway Arch 80 times a year. But they might see the Cardinals that often, if a new stadium was built.

In 1958, Ferris suggested the idea of a new, modern ballpark as the anchor to the redevelopment zone with a tag of $20 million in private financing and an additional $6 million in public upgrades to roads, sidewalks, etc. around the facility. To no one’s surprise, Gussie Busch was the first to get in the investment line, pledging on Anheuser Busch’s behalf to contribute $5 million toward the stadium. Others followed suit, with locally based May Department Stores providing the next biggest chunk at $2.5 million; even the St. Louis chapter of the Baseball Writers’ Association of America pitched in with a $1,000 donation.

Most everyone was thrilled with the concept of the new stadium and the surrounding redevelopment. Some weren’t. The minority was mostly made up of folks living in the area slated to be demolished, including a small but active Chinatown community (better known to St. Louisans as “Hop Alley”) and several businesses of ill repute. But they were in the way of progress, and after decades of stagnation in St. Louis, priority would be given to the stadium over strip clubs and sweet and sour pork.

Busch Memorial Stadium undergoes construction along with one of its two parking garages (in foreground), as seen here from the just-completed Gateway Arch. Many of the darker colored buildings on the far side would be demolished as part of the redevelopment effort south of downtown St. Louis. (Flickr—Missouri State Archives)

Even outside the demolition zone, there would be turbulence. Though the general city population loved the idea of a replacement for Sportsman’s Park, they weren’t keen on the idea of providing the $6 million in public works money. They got to vote on it in January 1962 and said no, putting the entire project in jeopardy. The politicos gave them two months to think about it in advance of another vote in March—which, this time, barely scraped the two-thirds majority needed for passage.

A Vision Set in Stone.

Leading the charge on designing what originally was called Civic Center Busch Memorial Stadium—the “Civic Center” was dropped early on—was Edward Durrell Stone, the New York-based architect known for visualizing Radio City Music Hall and the Museum of Modern Art in New York City, and the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in Washington. Under his wing were two St. Louis firms, including Sverdup & Parcel—which later had a hand in building the Louisiana Superdome but was more known for its bridges. One of those was the doomed I-35W bridge in Minneapolis that collapsed in 2007, killing 13. Fortunately, Busch Memorial Stadium wouldn’t experience a similar fate until the wreckers purposely brought it down in 2005.

Stone gave Busch Memorial Stadium his personal touch of class, a mix of decidedly modern and quasi-minimalist styles, with more of a hint of Romanesque features than seen within his other famed works of art. Cognizant of St. Louis’ hot summers, Stone also gave the enclosed facility gaps of airiness—especially behind the outfield walls—where breezes could file through to cool off sweltering fans. On the open, outside concourses, Busch Memorial featured undulating ramps, elegantly spaced concrete pillars and decorative ceilings which might have led early patrons to wonder whether they were going to watch baseball or the opera. Sportsman’s Park this surely was not.

Topping Busch Memorial was an overhang featuring 96 openings in the shape of Saarinen’s Gateway Arch, sloping inward and above the upper deck. Even if the idea was borrowed, it was a masterstroke; intended as a synchronistic homage, the “Crown of Arches” would become Busch Memorial’s signature look, enhancing the brand for a new St. Louis.

Busch Memorial as a finished product was far different from its original vision, which was that of a pure ballpark with an upper deck stretching only from pole to pole. That changed when football’s Chicago Cardinals moved to St. Louis in 1960 and provided the impetus to make the new stadium multi-purpose in character and be conveniently set up for both the Cardinals and Cardinals, who were probably taking cues from old New Yorkers (who once had two teams named the Giants) on how to market and differentiate one Cardinals team from the other.

There was no shortage of interest in the redevelopment zone around the emerging stadium. Potential tenants were hot to fill up two planned 20-story office towers. A sprawling new hotel, optimally placed along I-70, would provide guests with easy and equal walking access to both the stadium and the Arch. Restaurateurs were chomping at the bit to set up new shops. A deal was made to relocate the Spanish Pavilion from the 1964 World’s Fair in New York. Even Walt Disney, who grew up in Missouri, wanted in on the act—visualizing a Main Street-like recreation of St. Louis two blocks north of Busch Memorial; Disneyland Midwest looked like a go until Disney set his sights on the abundance of available swampland in Florida and reset his priorities toward Disney World at Orlando.

“It Holds the Heat Well.”

A labor strike of hod carriers pushed the grand opening of Busch Memorial back a month into the 1966 season; neither the Cardinals nor their fans were in no mood to return to old Sportman’s Park/Busch Stadium for another month, with barely 8,000 showing up for the Cardinals’ home opener while the team lost seven of 10, including its final four, at the old yard. But yesterday finally became today on May 12 as the gates opened at Busch Memorial for a crowd 46,048, the largest for any sporting event in St. Louis to that point, filling the new joint. One of those in attendance was former Cardinal Ray Blades, who at age 69 sat near the top of the third deck and pleasantly lamented, “Fifteen more feet up and I’d be in heaven.” Another was Edward Durrell Stone, the venue’s architect, who obviously felt proud of his achievement. “Now I know how Nero felt when he sat in the Coliseum,” Stone said, refusing to give an emperor’s thumbs down.

The Cardinals at bat before a packed house during its inaugural season at Busch Memorial Stadium in 1966. Note the roughened condition of the grass; it would soon give way to artificial turf. (Flickr—Missouri State Archives)

The team didn’t totally turn its back on Sportsman’s, the home plate for which was transported to Busch Memorial—not by Gussie Busch’s Clydesdales, but by helicopter. The Cardinals had to fight to win the inaugural game, scoring a run in the bottom of the ninth to tie the score before winning it three innings later with the help of the visiting Atlanta Braves, who loaded the bases by hitting Curt Flood, committing an error on a rare Orlando Cepeda sacrifice bunt attempt, and intentionally walking Charley Smith; Lou Brock next singled home the game-winner. It warmed the hearts of St. Louis fans who shivered all evening in temperatures barely above 50 degrees without relief from warm concession perishables because there weren’t any—the stadium’s gas lines had yet to be activated, severing any chance to make hotdogs, hot chocolate or any other food item with the word “hot” in it.

As the season progressed, it became evident that the heat, not the cold, would provide Cardinal fans with the bigger weather-related headaches at enclosed Busch Memorial. The 1966 All-Star Game at the new venue would showcase not only the game’s greatest talent but, also, the St. Louis summer at its scorching worst. After the National League labored for 10 innings and a 2-1 victory in 105-degree heat, honorary NL coach Casey Stengel was asked what he thought of the new Busch. “It holds the heat well,” he deadpanned. At least the 75-year-old Stengel made it through the day without suffering from heat exhaustion; 150 others within the stadium weren’t so lucky.

Pitching In.

Enough fans braved the heat to rotate the turnstiles at Busch Memorial 1.59 million times in 71 home dates in 1966, raising the bar on the Cardinals’ attendance record. Beyond the architecture, the patrons were likely lured by many of the other modern touches the stadium provided, such as the upscale Stadium Club that boasted fine dining along with a view of the game, and two outfield scoreboards each measuring 145 feet long by 21 feet high and costing $1.5 million—a gaudy sum for its day. With 35,000 lights and miles of wiring that could power a town of 2,000, the dual scoreboards also featured a neon cardinal in flight—accommodated by a chirping noise reverberating around the stadium—whenever the home team went yard.

Problem was, going yard didn’t happen very often at Busch Memorial. In their first season, the Cardinals hit only 41 homers and averaged 3.4 runs per game, compared to the 68 and 4.7 generated at Sportsman’s/Old Busch the year before. The pitchers didn’t mind and the team overall played well at New Busch with a 40-31 mark, but the field dimensions—with symmetrically healthy gaps of 386 feet and a straightaway distance of 414—was going to make stat-grabbing life difficult for power hitters who normally didn’t pull toward the foul poles, 330 feet away.

But pitching would become king in the late 1960s throughout baseball, and the Cardinals gladly followed the momentum at Busch Memorial. Getting used to the new stadium, the Redbirds captured consecutive NL pennants in 1967-68 with a stifling staff led by Bob Gibson in his prime and, among other up-and-comers, a young Steve Carlton. Gibson’s incredible 1.12 ERA in 1968 buffeted a league-leading 2.49 staff ERA (it was 2.23 at Busch), but even his World Series theatrics weren’t enough to give the Cardinals a second straight world title, losing to Detroit in seven games after having defeated the Boston Red Sox by the same count the year before. There was chatter of bringing in the fences after 1968, but Gibson probably talked the Cardinals out of it with a touch of motivation akin to his trademark up-and-in fastball.

While Gibson and speedy outfielder Lou Brock were emerging legends at the new Busch, the Cardinals aptly paid tribute to those of the old Busch. In 1968, the first statue was erected outside of Busch Memorial’s main entry when Stan Musial was immortalized in bronze; 10 more would follow in the decades to come, from Rogers Hornsby to Dizzy Dean to Gibson, Brock and Ozzie Smith. The Cardinals would also give bronze nods to local Negro League legend James “Cool Papa” Bell and even the old St. Louis Browns with a statue of 1920s hitting star George Sisler. Musial himself lived to see them all go up and likely summed it up in one word: “Wunnerful.”

Burning Men.

By the end of the 1960s, it appeared that the grass at Busch Memorial just wasn’t winning out over the summer heat. Compounding its health was the constant pounding the football Cardinals administered upon the turf as the weather turned cold and miserable. The condition of the field got so embarrassing that groundskeepers resorted to painting the grass green for the 1968 World Series to make it look good for national television. Players complained, but they would have taken it all back had they known that their gripes would be answered with the introduction of artificial turf.

In 1970, Busch Memorial Stadium became the first outdoor major league venue (along with San Francisco’s Candlestick Park) to entirely replace its grass with fake turf. Financially, it made sense; philosophically, it didn’t. The players, in step with the game’s purists, detested the stuff. Its resilience led to infield hops off the front of the plate that jumped as high as 100 feet. Its hardness made legs sore and line drives in the gap accelerate to the speed of light. Its lack of forgiveness led fielders to prepare for “carpet burns” whenever they dove for a ball at the edge of their defensive range.

If all of that wasn’t enough to swear off Christmas cards to Monsanto, there was this: The artificial turf made the field level at Busch Memorial Stadium, which was hot enough in mid-summer with real grass, into a virtual oven. To major leaguers, Death Valley in July would have been a cooler alternative. TV networks always loved to start a summer broadcast at Busch Memorial by sticking a thermometer on the field to show just how hot it was. Sometimes, it would read a whopping 150 degrees. To avoid burning feet, some players resorted to wearing aluminum foil in their innersoles.

After the Cardinals meandered through a mundane decade at Busch Memorial in the 1970s with yearly records constantly at .500 (give or take a few percentage points) and attendance constantly hitting 1.5 million (give or take a couple hundred thousand), Whitey Herzog drove I-70 from Kansas City, where he had built the Royals into a success using pitching, speed and line drive power on an equally fast artificial surface at Royals Stadium during the late 1970s, and took over the Cardinals’ managerial reins with the idea of doing the same at Busch Memorial. St. Louis was about to be introduced to Whiteyball.

Deadball, 1980s Style

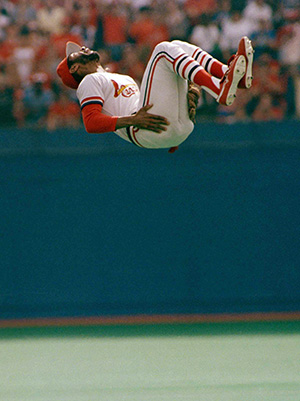

Under Herzog’s feisty direction, the Cardinals would make the 1980s Busch Memorial’s era of glory. Both they and the balls they hit darted about the fast fake turf, while consistent solid pitching and exceptional defense made them about as dangerous as one team could be without having to lean on power. Speedy switch-hitters ruled, from 1985 MVP Willie McGee to second baseman Tommy Herr to über-speedster Vince Coleman, who swiped 100-plus bags in three straight years. But the Cardinals’ icon for these times would undoubtedly be shortstop Ozzie Smith, who marveled with his glove and put his joy for the game on display by wowing the fans with his signature backflips before the first pitch.

Perennial All-Star shortstop Ozzie Smith personified the joy of 1980s Cardinals baseball with his signature backflips. (Associated Press)

The newfound excitement at Busch Memorial swelled attendance, with the Cardinals’ first-ever annual gate of two million in 1982—followed five years later by their first gate of three million. Like most other Midwest major league cities, many fans came from out of town—which is why rain delays lasted forever, lest the Cardinals were going to tell a family from Jefferson City or Springfield holding a rain check to come back a month or two later to see the completion of the game.

Indeed, constant summertime thunderstorms kept Cardinals grounds crews busy at Busch Memorial—so busy, the team decided to employ an automatic tarp that would unfurl itself over the infield at the push of a button. Somebody decided to push that button before Game Four of the 1985 NLCS—and it rolled over the leg of an unsuspecting Vince Coleman, doing pregame exercises. The supersonic rookie was tagged out by a tarp doing one MPH, and he was lost for the rest of the postseason; although the Cardinals went onto beat Los Angeles to take the NL flag, Coleman’s absence in the World Series to follow may have been the biggest difference between the Cardinals winning the Fall Classic and losing it—Denkinger’s blown call notwithstanding.

When the Cardinals became sole occupants of Busch Stadium in 1996, they beautified the venue with a return to real grass, a picnic area behind the bleachers and an expanded, hand-operated scoreboard in the upper deck. (Jerry Reuss)

Big Mac Attack.

As Whiteyball and retro deadball slowly gave way to a more modern power game at St. Louis in the 1990s, Busch Memorial Stadium would find itself undergoing change—slowly at first, then all at once.

The “all at once” part came in 1996, a year after the final football game had been played at the multi-purpose stadium by the St. Louis Rams, readying a move into their own domed stadium. From this point on, the Cardinals would have Busch all to themselves—and they were going to make sure it stayed that way. The moveable lower bowl of seats was permanently locked into baseball place, the fake grass was discarded for real sod, and a picnic pavilion was added behind the bleachers. A sense of intimacy—and even old-time charm—was introduced as well when 3,000 upper deck seats behind the outfield were ripped out and replaced with a 270-foot-wide hand-operated scoreboard, itself surrounded on each side by a display of honorary flags—one side representing the Cardinals’ world titles, the other the team’s retired numbers. The internal makeover was never going to confuse Busch with Oriole Park at Camden Yards, but its newfound charm enhanced the existing notion that the facility was aging much better than its sterile cousins in Pittsburgh, Cincinnati and Philadelphia. Maybe a new ballpark had to be murmured for revenue-related reasons—but aesthetically, Cardinals fans seemed to be quite content just where they were.

On the field—more than a generation too late for Orlando Cepeda, Mike Shannon and Roger Maris, Busch Memorial’s original sluggers—the Cardinals finally got around to moving in the fences, by some 10 feet between the power gaps; they also reduced the wall height from 10.5 feet to eight.

These reductions impacted the box scores. Only three times in Busch Memorial’s first 26 years had the Cardinals and their opponents muscled up to hit a combined 100 home runs, with the taller wall at its original distance; with the fences shortened and moved in, the stadium never again yielded less than 100. The Steroid Era was partially to thank.

Which leads us to Mark McGwire.

If the refurbished Busch was looking for even more intimacy, McGwire’s arrival midway through 1997 provided it—because no seat, no matter how far away it was, was going to be out of range from the Popeye-like slugger’s mammoth blasts. Future Hall-of-Fame manager Tony La Russa, once the boss of McGwire in Oakland and now in St. Louis, once bared witness to McGwire’s 49 homers as a rookie. But that was mere prologue to the unparalleled power display Big Mac was about to lay on Busch.

Mark McGwire turned Busch Stadium, once considered one of the toughest places to hit a home run, into a virtual bandbox in 1998 with 38 blasts at home among his record-shattering 70. Shorter field dimensions were partly responsible. So was McGwire’s use of PEDs. (Associated Press)

The prodigious spectacle put on by McGwire—accompanied by the Chicago Cubs’ Sammy Sosa, who chased him on his record pursuit and also passed Maris in 1998 with 66 long balls of his own—put smiles back on the faces of St. Louis fans angered by the 1994-95 players’ strike, as attendance at Busch Memorial catapulted back over the three million mark.

Ray Lankford, McGwire’s teammate in 1998, would wind up as the all-time home run leader at Busch Memorial with 123. McGwire was right behind with 119, though he needed only 280 games—nearly a third of those played by Lankford—to get there.

McGwire’s power surge was hardly the only impressive feat seen throughout the years at Busch Memorial. There was Pedro Guerrero, who as an opponent hit .373 at the venue; the Cardinals were so impressed that they finally traded for him. There was Kevin Mitchell, who hit .353 with 10 home runs in only 116 Busch at-bats—though he’s best remembered for making a running bare-handed catch of a fly ball beyond the left-field foul line. There was oddball ace Steve Carlton, who in his early incarnation as a Cardinal tied a then-major league record with 19 strikeouts in a 1969 home start against the Miracle Mets—and later as an opponent won 14 games (including his 300th overall in 1983), more than any other pitcher at Busch against the Cardinals. There was John Tudor, who in his brief tenure as a Cardinal was nearly unbeatable at Busch, registering a 35-8 record and 2.25 ERA. And finally, there was the all-time wins leader at Busch Memorial—and no, it wasn’t Bob Gibson; instead, it was Bob Forsch, claiming credit on 93 victories, including the only two no-hitters ever thrown at the stadium.

A Muddled Nod of Quiet Thanks.

The final years at Busch were hardly representative of a lame duck environment. The Cardinals, now powered by young socko star Albert Pujols—taking the mantle from McGwire, who quickly faded in 2001—and strong pitching anchored by Matt Morris and Chris Carpenter, won five divisional titles from 2000-05, missing out only in 2003 when the team finished just three games out of first. Attendance steadied at a minimum of three million per year. St. Louis won a last pennant at Busch in 2004, but failed to cap a third World Series crown when they obliged the Boston Red Sox with their first world title since 1918.

A new retro-style ballpark, the footprint for which would overlap Busch’s outfield, had been approved in 2002 and was already under construction as the Cardinals played their final season at the old stadium in 2005. Fans and the media began looking back at the wonderful memories generated at the venue through its four decades of existence, though one memory had become bittersweet; that same year, Mark McGwire had been shamed into repeatedly pleading the fifth in front of a Congressional committee asking him if he had ever taken steroids. The feel-good times of 1998 had been tarnished, and local politicians even erased his name from a section of Interstate 70 in St. Louis, renaming it in honor of Missouri native Mark Twain instead.

Cardinal Nation hoped to see Busch go out with a victorious bang in 2005 after St. Louis finished the season with a NL-best 100-62 record, but was disappointed when the Redbirds’ road to the World Series was cut short at the NLCS by the Houston Astros, a wild card team who finished 11 games behind St. Louis in the NL Central. Not disappointed were construction workers for the new Busch Stadium next door, who knew they’d have an extra week or two to work on getting the new ballpark ready on time for Opening Day 2006. Fifty days after the final out at Busch Memorial Stadium, it was no more—demolished bit by bit, section by section, arch by arch.

The reaction of Cardinals fans to the erasure of Busch Memorial was something akin to a muddled nod of quiet thanks. Unlike the other “cookie cutter” stadiums that met their fate with the wrecking ball or explosives, Busch Memorial didn’t get brought down to the cheers of millions yelling good riddance. But some tears were shed; there was a sense among St. Louisans that the stadium had done its duty and faithfully fulfilled 40 years of service with honor. One fan at the last regular season game likely harbored a majority viewpoint: “I don’t think they needed to tear it down, but whatever.”

Had popular, long-time Cardinals broadcaster Jack Buck lived to see the end of Busch Memorial—he passed away three years before—he would not have hesitated to give the stadium its just due with his trademark phrase, “That’s a winner.” And as the dust cleared on the ruins, the new Busch arose and time wore on, legions of Cardinals fans would have sat back, quietly tipped their cap to the ghosts of Busch Memorial Past, and agreed.

The Ballparks: Sportsman’s Park Nestled at the corner of Grand and Dodier Avenues, the many iterations of Sportsman’s Park showcased a century’s worth of the best and worst of St. Louis baseball as the Cardinals cranked and Browns stank, where beer barons ruled and star hitters drooled within a hitter’s heaven. Its exhausting heyday put stress on a worn-out field and beat-up mesh screen that prevented home run records, allowing local fans to exceed their quota of National Pastime enjoyment.

The Ballparks: Sportsman’s Park Nestled at the corner of Grand and Dodier Avenues, the many iterations of Sportsman’s Park showcased a century’s worth of the best and worst of St. Louis baseball as the Cardinals cranked and Browns stank, where beer barons ruled and star hitters drooled within a hitter’s heaven. Its exhausting heyday put stress on a worn-out field and beat-up mesh screen that prevented home run records, allowing local fans to exceed their quota of National Pastime enjoyment.

St. Louis Cardinals Team History A decade-by-decade history of the Cardinals, the ballparks they’ve played in, and the four people who are on the franchise’s Mount Rushmore.