THE BALLPARKS

Chase Field

Phoenix, Arizona

(iStock)

Domed facilities have always been necessary to keep out rain, cold, snow, humidity and mosquitoes. But why plant a roof in an idyllic sun-splashed destination like Phoenix? Remember, winter tourists, the off-season occurs in summer—when the ground bakes at triple digits even after sunset. The people behind Chase Field certainly kept that in mind, but just to keep things fair, they threw in baseball’s most famous swimming pool.

(iStock)

At first glance from afar, Chase Field looks like an aircraft hangar that’s wandered off from nearby Sky Harbor International. But on closer inspection, the character starts to emerge. A mix of old-fashioned brick and modern steel gives the facility more warmth. Action-packed color is added to the north side, where large murals of ballplayers loom high above the folks assembling to enter below.

As you walk around Chase Field, you do sense a struggle taking place between the past and present. There’s old-fashioned relief art of ballplayers adorning the main entry façade. There’s the sculpture on the north end showing a player “passing on” the game to a youngster and his mom “so that Arizona’s children will grow up knowing the rich tradition that has made baseball America’s national pastime,” or so the inscription says. There’s the kiosks of history, both local and otherwise, that permeate the ballpark’s main concourse inside. But then there’s the solar panels. And the signature swimming pool. And the retractable roof, that monstrous roof that’s ridiculed for its looks but praised for preventing heat stroke from the searing outdoor sun.

It’s hard to describe Chase Field effectively in a single word. Massive, perhaps. It’s built on 22 acres and, with the roof closed, rises to 275 feet; the Houston Astrodome, once the eighth wonder of the world, could almost comfortably fit inside it. Or scandalous, in the eyes of taxpaying citizens who never got to vote on whether they wanted the ballpark in the first place. Or overstimulating, with its thunderous sound system and inescapable saturation of revenue-driven advertising. The expansion Diamondbacks may have bent over backwards to inject tradition into the structure—when there really was none to speak of beforehand, the Cactus League notwithstanding—but in a building that could be mistaken for a shopping mall on steroids, capitalism rules the day. Tradition, in this ballpark, doesn’t stand a chance.

Schizophrenia aside, Chase Field can’t easily be dismissed. It may not be the ideal place for a purist to watch a major league game, but it is fun and worth the click of a turnstile, at least once. So yes, it’s not Fenway Park nor is it Wrigley Field. It’s Chase Field.

Break Out the Snake Oil.

As Major League Baseball began floating out trial balloons for a new round of expansion in the late 1980s, Phoenix tried to get in line. It got muscled out, by Miami and Denver. A few years later, MLB looked to expand again. This time, Phoenix arose as a top candidate. But just to be sure, the effort was fronted by Jerry Colangelo, a Chicago native who first arrived in Arizona during the 1960s as a front office executive of basketball’s Phoenix Suns before eventually buying the franchise, and ascended so high up the state’s totem pole of power that, by the early 1990s, he became a “yes man” to none. Colangelo was a magnetic presence, one who could read the room and take command of it. His emergence as the potential new lord of an Arizona baseball team all but ensured Phoenix automatic entry into MLB.

But that was the easy part. In order to cinch the deal, a ballpark had to be approved and built. Colangelo had the power to help green-light the facility, but neither he nor the numerous investors who pledged to finance the new team had enough additional money to fully fund it. He was going to have to lean on public dollars.

Phoenix residents had firmly stated, by a 2-to-1 ratio in 1989, that no major sports facility would be built without a say at the ballot box. Fearing that this was a pretense to defeat any such measure, politicians performed a sly end-around by transferring ownership of the existing stadium district from the City of Phoenix to the County of Maricopa.

Assured that if they built it, MLB would come, the county’s five-member Board of Supervisors went about proposing a quarter-cent sales tax to publicly fund $238 million for a ballpark, with Colangelo and Company kicking in another $40 million. All this, while both the city and county were facing budget shortfalls into the tens of millions. The Phoenicians were, to say the least, not pleased with the proposal—nor were county citizens outside the city limit who now felt suckered into the issue.

Relief art of an old-time catcher wearing his mask near the main entrance. It’s one of the few nostalgic touches dotted upon an otherwise very modern ballpark. (Flickr—Eric Okurowski)

Public polls taken before the Supervisors’ vote showed a definitive majority against the tax raise; the area’s two main newspapers had a different opinion. The Phoenix Gazette said that “a few pennies a day won’t break anyone’s budget,” while the Arizona Republic declared that a defeat would be the “biggest baseball surprise since Boston decided to sell Babe Ruth early in his career to the New York Yankees.” Both papers had incentive to lobby; they were part of Colangelo’s investor group.

In February 1994, three of the five supervisors said yes to the tax increase. The ballpark was a go—and so were the Arizona Diamondbacks, officially given birth by MLB a year later.

The supervisors who voted thumbs up for the ballpark would pay a heavy price for ignoring the will of the citizens. Two of them were roundly trashed in subsequent elections. They were the lucky ones.

Ballpark über-proponent Mary Rose Wilcox, the third, was leaving a board meeting several years later when a homeless man, angered over her approval of the venue and the “dictatorship” of Colangelo, pulled a gun out of a paper bag and shot her, shattering her pelvis. Wilcox survived and was even re-elected numerous times. The assailant, meanwhile, had to determine what constituted a more cruel and unusual punishment: The 15-year sentence he received, or the fact that his trial was originally scheduled to begin on the day of the ballpark’s grand opening in 1998.

There was the usual fruitless lawsuit filed by grass-roots activists seeking to repeal the tax increase, predictably squashed by a judge’s gavel. A more promising effort to get tax dollars reimbursed to county residents took place in 1996 when a state legislature committee considered adding a $5 surcharge on Diamondbacks tickets. It fell short of approval by a single vote.

In Search of a Soul.

There was little debate that the ballpark needed to be anywhere else but downtown. But there was big worry; downtown Phoenix was always a business center by day, ghost town by night. “Nobody goes there except to work,” The Seattle Times said, “Nobody seems to live there.” Sure, the ballpark induced starry-eyed visions among local politicos that a vibrant urban renaissance full of trendy restaurants, condos and entertainment would follow. But Phoenix, a boundless, diffusive valley city with no spiritual center, would prove a most difficult challenge in emulating Chicago, Denver, San Francisco and many other major league cities before and since where the gravitational pull of chic development around ballparks became inevitable. Here, the more fashionable suburbs and outlying resorts ruled the land. A high rate of retirees and insufferable traffic jams provided no help.

Still, the new ballpark had to be built downtown, and built specifically on the corner of Fourth Street and Jefferson at the city’s southeast edge so it could form a web of attraction in the surrounding blocks that would include the Suns’ home arena, the Phoenix Convention Center, the Phoenix Symphony Hall and the newly-upgraded Arizona Science Center. It was idealized that a ballpark would initiate momentum that would spread south of the ballpark site, where dusty blocks half-full of ramshackle businesses, cluttered warehouses and unattractive residences reigned amid the chain-link fences and tumbleweeds.

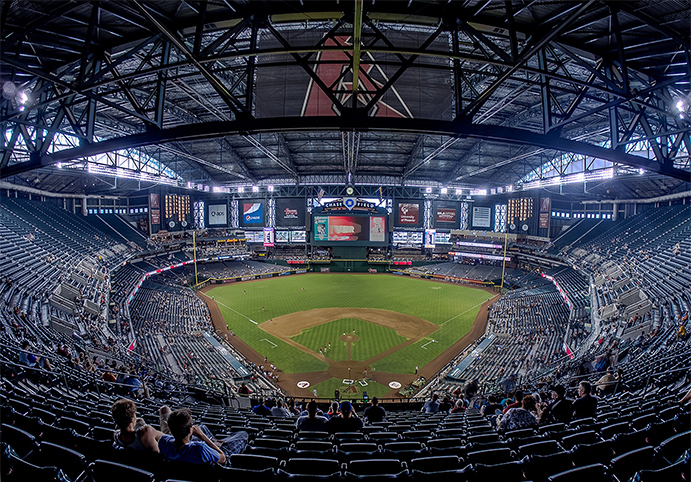

The complex, industrial make-up of the Chase Field ceiling is exposed in this shot from atop the upper deck one hour before the first pitch. (Flickr—Bob James)

The Stadium District, egged on by Colangelo, put on the blinders and sought the desired location—even as abundant land was being offered completely gratis just west of downtown. A total of $9 million in offers—ultimatums, really—was dangled in front of site’s current property owners to move out. One of them, Phoenix Newspapers, Inc.—owners of the aforementioned Gazette and Republic and minority investors in the Diamondbacks—happily took $2 million to relocate its storage facility. The other landowners held out and sued for more money, leading to a settlement.

Then there was the sad case of Beatrice Villareal, an 87-year-old woman who had lived her entire life in a small, tin-roofed home built 100 years earlier when Phoenix was little more than a blip on the desert map. Eventually the home found itself on the wrong side of the tracks, and in the wrong place when the Stadium District asked her to vamoose so the ballpark parking garage could be built. Too frail to sue, Villareal left; Colangelo, fearing an ugly PR tsunami, relocated her to a nicer place and promised to take care of her for her remaining days. Alas, those days were few; Villareal, likely traumatized by the move, died two months later.

Closing Out the Heat.

The weather in Phoenix is perfect—in March, that is, when major league teams congregate for Cactus League sessions as they have since 1947, and in the fall when the Arizona Fall League plays out its short schedule showcasing many of the game’s best prospects. In between, it’s Dante’s Inferno. From the end of May thru mid-September, the average high temperature is at least 100 degrees—and on some summer nights it stays above 100 well after sunset. The defense was often this: “Hey, it’s a dry heat.” Can’t say that anymore, claim the locals—who swear that Phoenix has become more humid and monsoonal over the years. Maybe it’s global warming, or the region’s increased urbanization, or just selected memories.

Regardless, it was unanimously determined that no major league ballpark could work in Phoenix without shading its fans. But it was more difficult than that; a natural grass field was sought, meaning that whoever was given the task of designing the ballpark had to find an optimal way to expose the turf to direct sunlight while keeping fans cool in the summer heat.

Bill Johnson, lead architect for Kansas City-based Ellerbe Becket, knew that a retractable-roofed facility with real grass inside would be a first. And while other architects competing for the job went Futurama on sketches, he had something simpler in mind. “When we went in to see Colangelo, we told him there were are all these unknowns and the last thing we need to do is make some highly automated, technical solutions,” Johnson recalled to the Sports Business Journal. “We need to use tried-and-true technology … and that’s the way it went.”

Johnson devised a solution consisting of eight separate panels—four on each side of the ballpark—that would close in cascading fashion using boxcar-like wheels rolling on two steel trusses. It’s a conventional method often used by giant gantry cranes at shipyards. The roof would open or close in just five minutes at a cost of a few bucks, a straightforward approach to a novel challenge as Johnson would later say. The Diamondbacks were won over; Johnson and Ellerbe Becket were in.

From the upper concourse, it’s hard not to notice the massive piping and ducts that fuel Chase Field with over a million cubic feet of air conditioning ever minute. (Flickr—Eric Okurowski)

Once the roof was built and shut, the next trick was to keep Chase Field cool; after all, standing under a shady tree in 100-degree weather doesn’t mean it suddenly feels like 78. Somewhere, an AC switch needs to get turned on. But trying to keep the air artificially cool at a rate of 1.2 million cubic feet per minute is a bit more challenging in a massive, enclosed ballpark than your average living room. Ellerbe Becket worked with experts who intensely studied the atmospherics and determined how to keep Chase Field from being too hot—or too chilly—with the roof closed. In the end, the ballpark culls its energy—enough to energize a city of 25,000—from a plant located right across the railroad tracks, one of three such downtown facilities producing roughly 1.5 million pounds of ice every summer night to keep folks cool inside the following day. And not only does the air inside the ballpark feel cool, so do the seats; chillers based under home plate are dispersed through 12 airhandlers to flow under the stands.

Walk along the upper concourse and look up, and you’ll get a good idea of the ballpark’s enormous HVAC complexities. It’s an overpowering sight of massive ducts, piping and maintenance stairways that criss-cross about, part of the pregame process in which the roof is closed three hours before the first pitch and the air cooled up to 30 degrees to a target of 78.

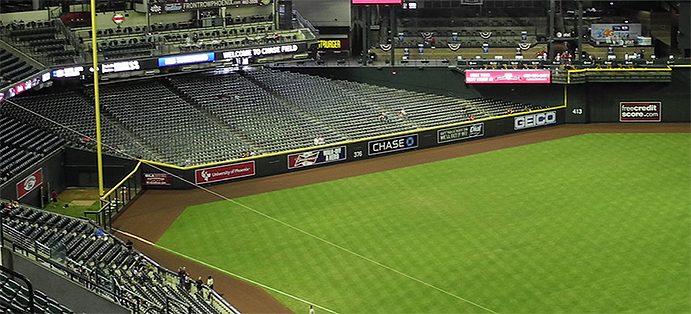

The out-of-town scoreboards, located high up and behind both foul poles, have a look reminiscent of totem pole-like leaderboards at auto racing venues. (Flickr—Eric Okurowski)

The roof isn’t the only open-air option at Chase Field. Above the outfield bleachers stand a dozen 32-ton panels measuring 30×60 feet that swivel open in 90 seconds to allow in tolerably warm air and desert breezes. When closed, people on the outside see colorful images of the Diamondbacks in action on the panels. And what do fans inside see on the other side of the panels? But of course: Ads.

Richie Sexson owns the record for the longest official home run ever hit at Chase Field, but he never hit it out of the ballpark. Mark McGwire did. In the midst of his memorable 70-homer season of 1998—the venue’s first year—McGwire launched a massive batting practice shot that bounced through one of the panel openings and onto Jefferson Street. The ball was never found.

H2Oh!

Air conditioning wasn’t the only dose of modern Arizona kitsch to be applied to the ballpark. Design discussions yielded the single most distinctive element of Chase Field: The pool. Originally imagined behind center field, it was moved to right-center because the batter’s backdrop would make it problematic for swimmers to watch the game. Even with the see-through chain-linked fence separating the field from the pool, batters aren’t so much distracted as are the bleacher fans who sit nearby and try to stay focused on the game while attractive, bikini-clad occupants sometimes splash about within their peripheral vision.

The Chase Field pool in action. The better looking the swimmers, the tougher the concentration on the game from spectators sitting immediately behind. (Flickr—Ryan)

The pool isn’t incredibly pricey; if you and 40 others can equitably split the bill for a little over $100 each, you can have it for a night. What you get is the pool, an adjoining Jacuzzi, food and drinks, field-level seating behind the right-field fence in front of the bleachers, a complimentary pool towel to take home and the presence of a lifeguard—so behave. The Los Angeles Dodgers didn’t on the night they clinched the National League West in 2013 with a victory over the Diamondbacks; after celebrating in the clubhouse, they all ran back on the field, jumped the fence and crashed the pool party, most of them still wearing their uniforms. It so inflamed the locals that even long-time Arizona Senator John McCain tweeted his disgust by calling out the Dodgers as “overpaid, immature, arrogant, spoiled brats.”

During the 2011 Home Run Derby that preceded the All-Star Game at Chase Field, another guy nearly crashed the pool—literally. Stupidly standing atop a flimsy table set against the retaining fence on the main concourse, the man lunged forward for a ball launched by Prince Fielder and began falling into the pool area; two quick-thinking people nearby somehow grabbed onto the guy’s legs and arms and pulled him back over the railing, 20 feet above the pool area. (Had he fallen, it wouldn’t have been into the water but, instead, head-first into the concrete on the side.)

Of course, home run balls are welcome to invade the Chase Field pool. On average, about five such “splashdowns’ occur every year. Mark Grace, before his three-year tenure with the Diamondbacks, was the first to do it in May 1998 while playing for the Chicago Cubs; he shrugged when told of the feat, joking that he’d hit the ball into the water before—“usually with 7-irons and 5-irons.”

One of the more underrated conversation pieces outside the lines at Chase Field is the main rotunda, which from the outside appears as a water tower morphed into the main building. The flooring inside pays tribute to Arizona with a beautiful 1930s-era marble map of the state; encircling it on multiple levels are murals of historic moments in the state’s history. Since baseball heritage beyond the Cactus League is almost non-existent in the Grand Canyon State, you’ll have to settle for Wyatt Earp and Doc Holliday.

Nobody Said This Was Going to be Perfect.

The construction of the ballpark was full of surprises, many of them unpleasant. Raising the trusses that hold the roof proved problematic, from a failing hydraulic jack to welding issues to a swarm of bees that collectively caused delays. A construction worker was electrocuted when a crane touched a power line that sent 7,200 volts through a pipe he was welding inside. Infighting grew between various contractors who frequently were not on the same page, likely the result of frustration with an accelerated timeline that led to nearly $100 million in cost overruns. While the Arizona Republic glossed over the issues and focused on how businesses were “jumping on the bandwagon” downtown, the Phoenix New Times—a local alternative paper that was not invested in the Diamondbacks—focused on exposing the problems. Disgruntled construction workers were slapped with a gag order from an irate Colangelo, but one of them—hopefully not speaking on behalf of the others—slipped through the ballpark cracks and told the New Times: “I hope the f**king thing falls down, and I hope it is full when it happens.”

Another, more lighthearted controversy came from the naming of the ballpark. It was announced that the Diamondbacks and banking giant Bank One agreed to a 30-year naming-rights deal that would yield $66 million, the majority of it going to the team. Bank One Ballpark: The fans hated the name at first, with one suggesting that it be called the B.O. Ballpark because it stinks. Yet they gradually came around—especially after it was shortened to the more lyrical and cute nickname of “The BOB.” When Chase bought out Bank One in 2004, the ballpark’s current name was soon after adopted, but no one has yet to come up with a perky nickname for it.

Drenched in Southwestern colors, a marbled map of Arizona welcomes fans into Chase Field through the main rotunda. (Flickr—Eric Okurowski)

Mixed reviews greeted the ballpark when it opened in 1998. The Sporting News called it a “veritable Disneyland of baseball.” Others were harsher in their assessment, comparing it to a “warehouse” or a “big cardboard box,” with some detesting the unfinished look of the ceiling with its matchstick montage of steel and tin. And while the AC was turned on, not everyone stayed cool. People sitting high up in the upper deck—like row 40, beholding a view worthy of the Grand Canyon’s South Rim—quickly learned the physics lesson that heat always rises to the top. It was worse for the poor souls outside who spent hours selling and taking tickets while exposed to the hot weather; misters located above the main entrance did their best to cool everyone off, and eventually the Diamondbacks extended the entry with a shaded structure topped by solar panels if, for anything else, to lower the turnover rate among day-game employees.

On the field, the biggest problem for the first-year Diamondbacks—besides losing 97 games—was the struggle of the customized grass that had been harvested in the California desert near Palm Springs. The heat wasn’t the issue; an unusually cool, wet spring made it difficult for the grass to thrive into summer, and by season’s end there were more than a few brown spots. A new sod, called Bull’s-Eye Bermuda—no, it’s not sponsored by Bull’s Eye BBQ Sauce—was planted the next season and it remains the turf of choice today at Chase Field.

A Complex Symmetry.

One small part of Chase Field where growing grass isn’t a worry is the dirt strip between the mound and home plate, the brainchild of charter Diamondbacks manager Buck Showalter and a throwback to olden days when such trails were common as catchers tended to wear out the grass running back and forth to chat with their pitchers. As Diamondbacks pitching suffered in its first year, it was joked that a dirt strip should also be planted between the dugout and the mound so Showalter and his pitching coach didn’t wear out that stretch of grass, either. (Showalter also devised a second warning track of sorts by planting a thin strip of grass between the dirt track and the fence, but it eventually was removed.)

Beyond the infield, Chase Field is essentially symmetrical—but hardly boring. There’s no curvatures, just sharp-angled turns. Near each corner of the outfield fence in front of the bullpen, a triangle-shaped nook takes a bite out of what is otherwise a straight line from pole to gap, presenting challenges to outfielders predicting caroms off the fence. Another straight section of wall connects the gaps in center field and is much taller at 25 feet as opposed to the 7.5 feet elsewhere; here, it gets curious with protruding balconies at the top of the wall that hang some six feet out over the warning track.

The Rorschach-like symmetry continues beyond the playing field. The massive scoreboard rests smack over center field, surrounded on each side by six of the swivel panels. High and well beyond each foul pole, an electronic out-of-town scoreboard stands vertically and could be confused for a leaderboard pole at NASCAR circuits. That there’s so much space to apply all of this to speaks to the sheer size of the building as well as the distribution of seating; only 15% of Chase Field’s 48,633 seats are behind the outfield wall. Packing the other 85% was made possible by the tall height of the upper deck (40 rows at its apex) and seats roughly a half-inch smaller than what’s used at other modern ballparks. That’s not because Diamondbacks fans have smaller waists; it’s because they’re not expected to lug in heavy clothing from the hot weather outside.

Sights to be seen beyond left field include Fridays Front Row Bar & Grill (left) and, over the tall center field wall at right, an extended overhang that juts out above the warning track. (Flickr—Eric Okurowski)

Enjoy, Hitters. Just Don’t Salivate Too Much.

The early years of Chase Field didn’t lack for excitement. The Diamondbacks were able to issue 36,000 season tickets for their inaugural campaign and drew 3.6 million fans, still a team record. They won 100 games in their second season and a world title in their fourth, capping the triumph with team favorite Luis Gonzalez’ walk-off bloop single in Game Seven over the New York Yankees and future Hall-of-Fame closer Mariano Rivera. Since then, the performance and chutzpah has waned, as has attendance—occasionally bottoming out at a flat two million.

Still, if you like high-octane offense, Chase Field is a preferred destination. At first glance, the field dimensions hardly look cozy with the deepest gaps measuring 413 feet away from home and topped by that 25-foot wall. But the hotter the climate, the friskier the hitter will feel about his prospects for a good day at the plate—even with the AC on, you hardly feel a chill inside an enclosed Chase Field. Here’s something else to factor in: The ballpark sits at 1,100 feet above sea level, the second highest elevation of any major league venue. Thus, the Diamondbacks and their opponents almost always produce more offense at Chase Field than they do on the road, as the ballpark has hit some five batting points and 15 slugging points higher over the major league average since its debut.

There’s been talk—and only that—about bringing in a humidor to deaden the baseballs, as has been done at Denver’s Coors Field. Otherwise, the field dimensions have remained the same since the very first game in 1998.

There have been adjustments over the years at Chase Field in terms of the fan experience. The ballpark originally opened with a Cooperstown satellite of sorts called Cox Clubhouse, which featured artifacts on loan from the Hall of Fame; it’s no longer there. More privileged amenities have popped up for those with fancier tickets, including two sponsored by Audi that provide fine dining and imbibing experiences. For everybody else, what was originally McDonalds, Blimpie’s and Little Caesar’s among the main concourse fare is now Burger Burger, Subway, Panda Express and Cold Stone. The one constant among the eating establishments since the ballpark’s opening has been Front Row Fridays, perched above the left-field bleachers; a sub-brand of TGI Fridays, the restaurant has extensive patio seating to watch the ballgame from and dispenses with the usual Fridays flair of flea market rejects, replaced here by various baseball bling. It’s open year-round and can be accessed directly from the outside, but if it’s game day and you don’t have a ticket, you’re going to have to scram 45 minutes before the first pitch.

More recently, the Diamondbacks made the interesting move of allowing local health club operator Mountainside Fitness open up a branch behind center field, the first time a gym not intentioned for ballplayers has been built within a pro sports venue. Word got around that Diamondbacks players became so jealous, they ditched their own, smaller weight room and started using the Mountainside equipment alongside regular club members. And to answer your other question: No, you can’t watch a Diamondbacks game from the treadmill—unless it’s being shown on a TV monitor.

The north end of Chase Field, with the roof and window panel doors open; below is Mountainside Fitness, the first public gym to be placed inside a pro sports facility. (iStock)

The expected evolution of downtown Phoenix from sterile business center to chic go-to among the local masses has not occurred in the wake of Chase Field’s opening. There was an uptick when the ballpark opened in 1998, but it was a brief one; life in downtown has since stagnated. Arizona State University has built a significant campus branch on the north end and, closer across the street from Chase Field, a high-rise condo development has been built, but growth has otherwise proceeded at a snail’s pace. The industrial area south of Chase Field, where the Stadium District was really hoping to see redevelopment and gentrification take off, has essentially remained untouched.

Part of the problem is that Chase Field ticket buyers can conveniently park in any one of two large parking lots adjacent to the ballpark, or they can get right off at its doorstep courtesy of the area’s fledgling light rail system. This has reduced the potential for abundant foot traffic in the surrounding blocks. You think this would have benefitted one microbrewery plunked in a plum spot just across the personalized bricks from the main entrance. Leinenkugel’s Ballyard Brewery, a Milwaukee-based chain that opened along with the ballpark and was co-owned by Hall-of-Famer Robin Yount, did great business for 81 ballgames—but largely sat empty during the other 284 days when baseball wasn’t on tap. The building is currently occupied by new ownership that goes by the name of Game Seven Grill, a touching tribute to that great time back in October 2001.

There is one popular spot outside Chase Field that, so far, has stood the test of time. Cooper’stown, located three blocks to the west of the ballpark, is named as a double entendre—a nod to both the Hall of Fame and rock star/Phoenix resident Alice Cooper, the restaurant’s owner. The menu includes “The Chicken Incident” Wings, Nightmare Nachos and Maniac Mac & Cheese, and is brought to you by servers dripping with Cooper’s trademark eye makeup.

While Chase Field exists purely as a baseball venue, other events have been wedged into its frame, including college football games, soccer exhibitions and the usual concert and monster truck fare; several college basketball games have been played there as well, both with the roof open—though in one case, they couldn’t close it fast enough when rain began to fall, canceling out the final few minutes of play.

In an era when retro themes threatened to become a redundancy in ballpark architecture, Chase Field emerged as a qualified departure. True, its mashing of nostalgia and modernity gives it something of a split personality, but for better or worse, there’s nothing else quite like it. But don’t listen to us. Let’s hear it from the public address announcer who declares to the crowd before the start of each game: “Ladies and gentlemen, boys and girls, welcome to baseball’s most unique experience…”

Indeed it is.

Arizona Diamondbacks Team History A decade-by-decade history of the Diamondbacks, the ballparks they’ve played in, and the four people who are on the franchise’s Mount Rushmore.