THE BALLPARKS

Cleveland Municipal Stadium

CLEVELAND, OHIO

Orderly as it was ordinary, obese as it was austere, Cleveland Municipal Stadium was that rare baseball structure of the early 20th Century, hailed not as a monument to a team owner but to civic pride in a city feeling its oats about the future. Golden moments would ensue, but rust would quickly overtake the stadium and its baseball tenant, rousing cynical locals to declare it “The Mistake by the Lake.”

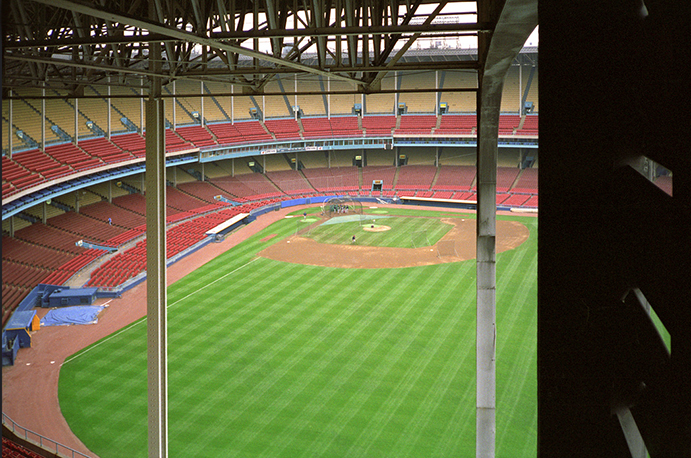

Worst things first: Cleveland Municipal Stadium was an oversized sea-stained relic, with seats too far away, a field and lighting system assailed as among the worst for major sports facilities, cramped locker rooms, ancient and odious restrooms, and a fan base that, infected by the stadium’s miserable atmosphere, unbottled its rage and launched the empties toward unsuspecting players.

That’s generally the opinion of those, mostly still among us, who experienced the stadium in its latter days when no amount of upkeep could keep it from decaying on a daily basis.

There is a counterpoint to this, and it comes from those who lived through the grander, earlier years of a stadium that stood magnificently along the shores of Lake Erie. The concrete then lacked cracks, the paint still looked fresh, and the sheer size of the facility—baseball’s largest at the time—beget a majestic aura and gave its citizens, who voted to build it, a genuine sense of purpose in a growing city searching for that booster shot of stout, communal confidence. Their pride was accentuated by the mid-century success of the stadium’s two main tenants: The colorful Cleveland Indians, and football’s upstart Cleveland Browns.

There’s an urban legend, debunked only in recent years, that Municipal Stadium was built on spec to attract the 1932 Summer Olympics; in truth, it was passed by voters five full years after the International Olympic Committee had already blessed Los Angeles as the host. Clevelanders assembled the stadium not to light a flame and welcome the world, but to let it know that it had arrived as a modern Great Lakes metropolis.

Thinking Big.

Like most American cities west of the Appalachians transformed by industry, Cleveland was experiencing booming growth, its population increasing at a rate of roughly 50% every decade from the Civil War through 1930. Its civic leaders weren’t just content with managing the growth, looking instead to beautify their city and turn it into a sort-of Rome on the Erie. In 1903, they established what was referred to as the Group Plan, an ambitious project in which the north section of downtown would be revamped into an expansive mall of grandiose structures within a stately, park-like setting to serve both the public and the city’s ego.

The Group Plan started slowly, even stalled, with World War I interrupting its best laid plans. But as America cut loose with the postwar excesses of the 1920s, it accelerated into top gear thanks to Cleveland’s first city manager, William R. Hopkins—yes, that’s the guy the city’s airport is currently named after. In short order, the mall sprung up with a city hall, public library, combo theater/arena, courthouse and Federal building, among many other impressive structures—all erected in a mix of Romanesque and French Beaux arts architecture. Inspired, other business leaders got into the act and added their own touch of marvel near the mall, including the linchpin Terminal Tower skyscraper.

The idea of a stadium as part of the Group Plan was not top of mind, but it was thrown around as a concept that could be built at the north end of the mall, atop a landfill along Lake Erie. Initial thoughts had the stadium seating somewhere in the 20-25,000 range, to be primarily used for high school and college football games; the lack of baseball within the conversation suggested that the field area would be shaped as a rectangle, not a pizza slice. And besides, the Cleveland Indians already had their own 20,000-seat venue in cozy League Park, recently converted into a steel-and-concrete facility.

But as the 1920s progressed and large municipal stadiums from Los Angeles to Columbus to Philadelphia became a hot trend across the country, Hopkins and Company resurrected the 20,000-seat stadium concept, thinking bigger—much, much bigger. They now considered an oval, multi-purpose monstrosity that would seat upwards of 100,000, welcoming the Indians as its first tenant. It’s not that they were worried that the Indians, under new ownership by Alva Bradley, were dissatisfied with League Park and would leave Cleveland. Instead, their concern was that the team would want to build its own ballpark, and thus reap all the revenue the city was eyeing with its own stadium. Hopkins wanted it his way, and lobbied Bradley into imagining Yankee Stadium-sized crowds and the revenue that came with it—even if the team had to share it with the city—to be a part of his vision.

Strong community support buoyed the proposed stadium, leading Cleveland’s City Council to approve a $2.5 million bond referendum in August 1928—with voters allowed to get the last say in November. Only one councilman, F.W. Walz, opposed the stadium and spoke for future generations of frustrated taxpayers covering the costs (budgeted and overbudgeted) and eternal debt of publicly-funded sports facilities when he explained why: “The stadium would never pay for itself, would cost more than anticipated, and would be a luxury.”

The voters did not heed Walz’ warning. They said yes to the bond measure with 60% approval.

With Municipal Stadium’s skeleton looming above, officials check out the remains of an accident that killed two construction workers in January 1931. High winds blowing in from Lake Erie were said to be partly responsible. (Cleveland Memory Project—Cleveland State University, Michael Schwartz Library, Special Collections)

A Big “C” for Cleveland.

The physical make-up of Lakefront Stadium, as Cleveland Municipal Stadium would initially be known, was a joint effort between two esteemed local firms. Osborn Engineering, the structural design giant responsible for work on nine other major league ballparks (including the renovation of League Park), partnered up with Walker & Weeks, architect of numerous Group Plan structures as well as Severance Hall (current home of the Cleveland Orchestra) and the Lorain-Carnegie Bridge, adorned with eight decorative guardians that inspired the Indians to change their name a century later. Together, these two firms drew up a mammoth structure based on stripped classicism—an early 20th-Century movement echoing art deco, neoclassical and Moderne styles with a minimum of embellishment, in stark contrast to some of baseball’s far more ornamental shrines in Philadelphia (Shibe Park), Pittsburgh (Forbes Field) and Brooklyn (Ebbets Field).

An oval base, clad in sandstone brick, was topped by a dark blue, upper-deck façade draped by louvered slats—principally constructed of aluminum—and covered by a horseshoe-shaped roof which, when viewed from south of the stadium, looked like a giant, extended “C” for Cleveland. Not covered was a single level of bleachers at the stadium’s east end, located so far away from home plate that no player ever reached it with a home run in over 4,200 major league games played at the stadium. Back outside, each end of the stadium was flanked by a pair of five-story, square-shaped structures protruding out of the oval base, giving the facility a civic sense of respect while providing focus at ground level to reduce the dominance of the oval.

Building the stadium would not be easy. Because it sat on a landfill where once was Lake Erie, thus offering less terrestrial integrity, more steel pilings needed to be drilled deeper into the underneath. The 5,100 tons of steel required for Municipal Stadium was more than double needed to build Yankee Stadium, baseball’s other titanic structure of the time constructed on far more stable ground. Cleveland’s lakeshore weather, which frequently elicited cold, wind-swept conditions even well into spring, also provided a challenge for construction efforts; two workers discovered this in the most tragic of ways when a makeshift tower they were near the top of collapsed in gusty, wintry winds, killing both.

Despite that awful moment, the massive project scope, and 11th-hour additions in a sound system, scoreboard and lights that added $500,000 to the budget, Municipal Stadium was completed six months ahead of schedule, just over a year after the first shovels were plunged into the ground. On July 3, 1931, two days after a stadium dedication that gave citizens their first look inside and out, the inaugural sporting event was held as boxers Young Stribling and Max Schmeling duked it out before a crowd of 40,000—half of what the city and promoters were envisioning.

Noticeably absent in Municipal’s first year of operation were the Cleveland Indians, for whom the city was dying to bring in as a tenant. The Indians were more than happy to relocate from League Park, but at the right price; the team squabbled with city officials over a lease, with no agreement reached. With League Park as a fallback, the Indians stayed put, collecting full revenue from a ballpark they owned.

In the meantime, spanking new Municipal sat relatively quiet; among the sparse highlights of activity was an opera festival, Shriners convention, and an expansion team in the fledgling National Football League, playing just two games at Municipal in its only season with 12,000 total fans before quickly folding. If was as if the city built a massive new stadium—and nobody came.

The very first game played at Municipal Stadium, won by the Philadelphia A’s over Cleveland, 1-0 on July 31, 1932 a crowd of 80,000—at the time, the largest to ever see a major league game. Note the sloping warning track and outfield wall in front of the bleachers, which measured anywhere from 435 to 470 feet from home plate. (Cleveland Memory Project—Cleveland State University, Michael Schwartz Library, Special Collections)

Relocate With Caution.

A year after Municipal Stadium’s opening, the Indians finally came on board—albeit tepidly, as the team signed a lease on a year-to-year basis, just in case. But their first game, played in beautiful sunny conditions on July 31, 1932, gave great hope that the stadium would be a boon for them—and the city.

A crowd of roughly 80,000, the largest to that point in major league history, welcomed the Indians, accompanied by commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis, both league presidents, heroes of Cleveland’s baseball past including Cy Young, Nap Lajoie and Tris Speaker, and a virtual aerial armada of biplanes and blimps in the skies above. Ohio Governor George White threw out the ceremonial first pitch, followed by a pitching duel with Cleveland’s Mel Harder succumbing to the incomparable Lefty Grove and the Philadelphia A’s by a 1-0 count. Beyond watching their team get shut out, the only frustration on the day for fans was returning to the parking lot and discovering that all their cars were coated with a layer of dust kicked up by traffic and lakeshore winds to such an extent that it was hard to distinguish one automobile from another. Once they figured out whose car was which, they experienced an insufferable jam trying to cross a pair of overpasses above railroad tracks that separated the stadium from the rest of the city.

Exterior issues notwithstanding, Municipal Stadium was greatly lauded by the dignitaries of the day. “Marvelous. The last word in baseball parks,” claimed National League president John Heydler. Commissioner Landis added, “It’s the only park I know where spectators can clearly see from any seat. Look at those people in center field, they can see every play.” Surely, more than a few people within earshot of Landis’ comments must have been aching to poke him in the side and remind him that (1) steel posts created obstructions in the backend seats on both levels, and (2) while no such interference existed in the bleachers, binoculars would become highly encouraged for fans sitting further away from the action than any other major league venue.

The Indians’ second game at the stadium, another 1-0 win for the A’s before a much smaller crowd of 9,000, all but confirmed the hitters’ worst fears that this would definitely be a pitcher’s park. One issue was that bleacher fans, as far away as they were sitting, still constituted a tough background of white shirts that hitters found difficult to spot a pitched ball out of; that was ultimately taken care of by roping off the middle portion of the bleachers. Then there were the field dimensions, which were all but impossible to overcome with a long ball. While the distances down the lines played fair enough at 320 feet before bumping into the permanent, curving lower level, the outfield walls stretched well back from there, with the gaps and straightaway center field measuring an ultra-distant 435 and 470 feet, respectively, from home plate.

Even the most powerful sluggers gave up on the idea of a home run, choking up more on the bat and concentrating on punching out line-drive hits. Not surprisingly, 10 triples were roped out at the new stadium before the first homer was recorded seven games in, by Cleveland’s Johnny Burnett. Hall-of-Fame star Earl Averill, who would hit a career-high 32 homers in 1932, would have certainly belted more had the Indians stayed at League Park over the season’s final two months; he hit only three round-trippers (most of any Cleveland player) over 32 games at Municipal Stadium while collecting 13 in 45 games based at League Park.

There was no bigger critic of baseball’s first year at Municipal Stadium than Babe Ruth. Earlier in what would be the final two games played at League Park before the Indians’ move into Municipal, the legendary slugger clobbered three home runs with nine runs batted in. But when his New York Yankees returned to Cleveland in mid-September and visited Municipal for the first time, he found an entirely different setting that challenged even his muscular magnitude. That Ruth would hit no home runs in 42 career at-bats at the stadium didn’t irk him as much as having to exhaustingly patrol a mass amount of outfield space while on defense. Ruth called Municipal Stadium a “cow pasture” and claimed that “a guy ought to have a horse to play the outfield.”

The Indians were no less thrilled with Municipal Stadium as they stuck it out at the voluminous venue through the entire 1933 season. The team played well there, but attendance for their first full season at the stadium was 387,936—a 20% drop from their last full schedule at League Park, which held a quarter of Municipal’s capacity. That it all coincided with the peak of the Great Depression, which hit Cleveland particularly hard, could be targeted as a culprit for the poor gate; but the Indians, having lost $200,000 on the year, couldn’t count on a mulligan to justify remaining at the stadium. So they moved back to League Park—and stayed there for the next two seasons—to “regain closer contact” with the fans and jumpstart an offense within a much smaller setting.

There’s much to reveal in this 1950s aerial shot of Municipal Stadium and the city of Cleveland beyond. Above and to the left of the stadium is The Mall, the city’s ambitious, park-like gathering of civic structures for which the stadium was an external component; the Donald Gray Gardens, separating the stadium from Lake Erie; and, on the other side, two bridges that provided fans with the only access to and from downtown, which led to massive wait times departing the stadium when filled to its 80,000-seat capacity.

Let’s Play at Two.

For the next three years, only two major league games would be played at Municipal Stadium: The 1935 All-Star Game, and an August 1936 contest with the Indians, stepping out of League Park for a day, battling the Yankees for 16 innings before darkness put a halt to a 4-4 tie; both games drew close to 70,000 spectators.

Otherwise, the stadium remained a virtual ghost facility, its calendar barely dotted with one-off events such as a 1934 college football game featuring Notre Dame and Navy—the second of 11 games played between the two teams at the stadium from 1932-78—and the Seventh National Eucharistic Congress, a two-day Catholic event that drew 200,000, with a Municipal-record 125,000 attending the second day. In 1936, the stadium became a useful component of the adjacent Great Lakes Exhibition, a popular World’s Fair-style event which beautified the coastal area around Municipal—particularly a horticultural display immediately north of the stadium entitled the Donald Gray Gardens, which stuck around through the end of Municipal’s lifespan in the late 1990s.

By 1937, the Indians began to envision the advantages of returning to Municipal Stadium—but only on a part-time basis. They scheduled weekend games, mostly doubleheaders, which often drew far more fans than what League Park could hold. Fifteen games were held at Municipal in 1937, followed by 18 a year later; with permission from the American League, the Indians in 1939 hoisted up lights at the stadium—the original lamps, part of the last-minute scope, were either long gone or replaced—truly making Municipal a part-time home with roughly 40 dates on average per season.

Having two home ballyards diametrically different from one another certainly must have messed with the rhythm of Cleveland hitters and pitchers attempting to reconcile the spacious Municipal Stadium—which averaged six runs per game between both teams—and League Park, with its pinball style of play generating over 10 runs per contest on average.

But the Indians’ home schizophrenia also provided them with opportunity. While the team’s home schedule was set before Opening Day, there still was fluidity in which home games would be played at which venue. This was done intentionally, to schedule more games against teams relying on the long ball at voluminous Municipal Stadium as the season went along for competitive purposes; and, for economic purposes, to maximize the number of starts (and attendance) at the bigger venue for Bob Feller, the exciting young Cleveland ace blessed with a supersonic fastball. Opposing teams fumed at the scheme and, by the early 1940s, the AL office demanded that the Indians decide exactly which games would be played at which park before the start of the season.

Maverick owner/promotion wizard Bill Veeck gets on the public address system and thanks another big crowd for showing up to watch the Indians in 1948. The vibe at Municipal Stadium peaked that year with the Indians winning the World Series in front of 3.4 million total fans, while football’s Browns finished 14-0 and won the All-American Football Conference championship. (Cleveland Memory Project—Cleveland State University, Michael Schwartz Library, Special Collections)

One Veeck of a Time.

The drab, quiet existence of Municipal Stadium’s early years came to an ear-ringing end with the arrival of Bill Veeck, the maverick promoter who bought the Indians in the summer of 1946. Veeck was baseball’s equivalent to Barnum & Bailey, a showman for whom no promotional stunt was too shameless—so long as it jammed his ballpark with as many butts as possible. That he had 80,000 seats to fill at Municipal didn’t intimidate him; on the contrary, he salivated at the thought of doing the impossible, to fill Cleveland’s cavernous coliseum on a daily basis.

And he damned near did it.

Veeck’s first order of business was to abandon the diminutive and increasing archaic League Park and go all in on Municipal Stadium, because 20,000 seats weren’t going to be enough for what he had in store. To lure bigger crowds, he did more than just open the gates and give fans nothing more to do than watch nine innings of baseball. There were giveaways, sideshows and postgame fireworks—all things common now, but trendsetting in the 1940s thanks to Veeck. “This is the entertainment business, not religion,” he once said.

Eschewing traditional ownership fashion by wearing sport shirts and slacks rather than suits, Veeck paid heed to more than just the typical blue-collar, white male baseball fan. Women, for so long a small minority at major league parks (except on Ladies Days), were a constant demographic target for Veeck, with giveaways of stockings and Hawaiian orchids, and an in-stadium nursery for moms to drop off little ones not quite ready to enjoy the game. African-Americans surely became more engaged to attend when Veeck quickly followed Jackie Robinson’s arrival in Brooklyn by bringing on former Negro League stars in Larry Doby and legendary pitcher Satchel Paige. Even the press got some love with the opening of the Wigwam, a private restaurant and lounge for reporters and team officials near the press box.

For Cleveland’s hitters, the full-time move into Municipal Stadium—where their numbers historically struggled—likely gave them a deep sense of melancholy, until Veeck sprang good news on them: He was moving in the fences some 60 to 70 feet between the gaps. “The American sports lover likes power,” Veeck told The Sporting News. “Time was when the fans admired pitching duels. Now they want action, runs. They want knockouts in the ring.” Home runs would finally become a thing at Municipal; the rate of round-trippers doubled in the Indians’ first full year with the moved-in fences.

Veeck fancied a flexible competitive advantage by shifting the fences back and forth during the season, depending on the opponent (for example, pushing them back when the powerful Yankees came to town). He even thought of doing this in the middle of a game; for one 1947 contest, he asked the manager of the opposing side, the Detroit Tigers’ Steve O’Neill, if he would be okay with the idea. O’Neill responded by telling Veeck that he was out of his mind. (The AL eventually created a rule barring the in-season moving of outfield fences.)

Both the fans and the players embraced Veeck’s nonstop parade of promotions and newfound balance between hitter and pitcher as the Indians drew 1.5 million fans in Veeck’s first full year of ownership, easily setting a franchise record. But that was mere prologue to what was to follow in 1948, when the turnstiles—and everything else—clicked for the Indians. Veeck, of course, threw everything but the kitchen sink into his promotions, but he also had the fortune of having a championship-level team thrown into his lap to publicize. Manager/shortstop/AL MVP Lou Boudreau batted .355, fellow infielders Joe Gordon and Ken Keltner each hit at least 30 homers with well over 100 RBIs, Bob Lemon and Gene Bearden (who survived a fractured skull in World War II) each won 20 games, Bob Feller added 19, and even Satchel Paige, at age 42, showed he still had it in a hybrid relief/starter role, as Cleveland fought the Boston Red Sox to identical season-ending 96-58 records. The Indians took the pennant via a one-game playoff at Boston, with Boudreau smacking two homers among four hits. In the World Series to follow against Boston’s other team, Cleveland rode outstanding pitching to defeat the Braves in six games.

Almost as headline-grabbing as the Indians’ lone world title based at Municipal Stadium was the record-shattering number of fans who came out to witness it. Official attendance at Cleveland for the 1948 season was 2,620,627, but those only counted the ones who paid; add in 457,994 freebies (mostly women on Ladies Days and kids) and another 325,000 for a pair of exhibitions and three World Series games (including 86,288 for Game Five), and the actual number of spectators in Cleveland’s big house for the entire season amounted to a staggering 3.4 million.

Thanks in large part to the Indians, not to mention big crowds that turned out for the third-year Cleveland Browns—who finished a perfect 14-0 in the All-American Football Conference—Municipal Stadium in 1948 finished financially in the black for the only time in 64 years of operation. The total profit: Two dollars.

Alas, the Bill Veeck Era in Cleveland would be short. After a 1949 campaign in which the Indians failed to repeat despite drawing another two million-plus fans, Veeck absorbed a costly divorce which forced him to sell the team. New ownership stayed the course, retaining Veeck’s top front office exec Hank Greenberg, the former Hall-of-Fame slugger who maintained Cleveland’s contender status through the emergence of Larry Doby, fellow ex-Negro Leaguer Luke Easter, third baseman and 1953 AL MVP recipient Al Rosen, reliable second baseman Bobby Avila, and one of baseball’s great four-man rotations in Feller, Lemon, Early Wynn and Mike Garcia—all four of whom rank at the very top of Municipal Stadium’s career win list.

The sideshow spectacles continued as well, even if they lacked Veeck’s genius audacity. In one odd mashing of cultures, baseball players shagged batting practice flies while the Cleveland Summer Orchestra performed pregame concerts beyond the center-field fence, hoping not to get dinged by deeper drives. And exaggerating the fact that the stadium was so big and the walk from the bullpen (perched in front of the distant bleachers) to the mound so long, the Indians began using a Jeep to transport relievers into the game. Yankees manager Casey Stengel refused to let his players hop in, stating “They’re used to Cadillacs.” When the Indians accommodated Stengel with his request, he still made his relievers walk.

Cleveland’s sparkling postwar period of baseball was capped with an impressive 1954 effort. The Indians won a franchise-record 59 games at Municipal and 111 overall (against just 43 losses) to clip the 1927 Yankees’ AL record by one; they also relegated the Yankees, who had won every AL pennant since Cleveland’s 1948 World Series triumph, to second place—driving the final nail into the Bronx Bombers’ coffin on September 12 when a club-record 86,563 jammed Municipal for a doubleheader sweep. (That crowd remains the largest for an MLB single-admission, regular season event.) Additionally, Municipal hosted its second, and most exciting, All-Star Game—featuring six home runs including two from the Indians’ Al Rosen as the AL outlasted the NL, 11-9 before 68,751 spectators. Hopes of another dream championship for Cleveland came to an abrupt and disappointing end as the Indians were swept by Willie Mays and the New York Giants.

A concession stand at Municipal Stadium, with a chain-linked fence providing a dubious aesthetic touch. (Cleveland Memory Project—Cleveland State University, Michael Schwartz Library, Special Collections)

The Browning of Cleveland.

The postwar rise of the Indians coincided with the emergence of the Cleveland Browns, giving Municipal Stadium a second solid tenant.

The Browns had been preceded by the Cleveland Rams, who like the pre-Veeck Indians bounced back and forth between Municipal Stadium and League Park. Born in 1937, the Rams never had a winning season until 1945, when they captured the NFL title with a 15-14 win over Washington in conditions so cold at Municipal, fans in the bleachers resorted to setting the wooden benches on fire to keep warm. It would be the Rams’ last game in Cleveland; news about a rival league with a well-funded local competitor persuaded them to relocate to Los Angeles.

Named after inventive young head coach Paul Brown, the Browns proved the Rams wise in their decision to move, dominating the All-American Football Conference with a 47-4-3 record with league titles in all four seasons before being merged into the NFL. The more established league didn’t slow the Browns down, as they reached the NFL Championship Game in each of their first six seasons, winning three—twice over the transplanted Rams. Brown’s posse of star players included three-time MVP quarterback Otto Graham, Hall of Famer Lou Groza—who for 21 years at Municipal uniquely doubled as lineman and placekicker, using an old-fashioned straight-toe style of kicking—and the legendary Jim Brown, still defined by many as the greatest running back of all time.

The Browns’ winning ways helped build a large and loyal following at Municipal Stadium with crowds frequently maxing out at its 80,000-seat capacity. Sightlines for football fans were just as bad—if not worse—than for those following the Indians, as the stadium’s oval configuration created acreage of sideline space; having a 50-yard line seat could have easily just as meant that you were more than 50 yards from the action. Perhaps the best football seats in the house were the bleachers, which practically sat on top of the east end zone; the loud, rough and rowdy fans who inhabited that space grew a reputation that, many years later, earned their section the affectionate name of the Dawg Pound. Opposing NFL players not only heard these crazed fans, they sometimes felt them—with bottles, batteries and other objects thrown in their direction. The littering sometimes got so bad that referees would switch the direction of opposing teams toward the other end zone, away from the Dawg Pound, late in the game.

The Curse of Rocky Colavito.

After a strong postwar run that spawned two pennants and a world title, the Indians gradually regressed through the latter part of the 1950s. Ownership changed hands twice, Hank Greenberg left to join Bill Veeck with the White Sox in Chicago, the vaunted pitching staff grew old, Al Rosen’s back gave out, and Herb Score—advertised as the Second Coming of Bob Feller—had his career badly curtailed when a line-drive comebacker smashed his face in 1957. Attendance at Municipal Stadium sank along with the Indians’ place in the AL standings, dropping back below a million in 1956. That same year, the team drew a paltry 365 fans—or 1/237th of their record gathering against the Yankees just two years earlier—for a meaningless late-season game on a wet September afternoon.

Municipal Stadium was given character in 1962 with the appearance of the iconic (and later controversial) Chief Wahoo caricature swinging a bat as part of a roadside-style sign atop the Gate D bleacher entrance. The 29-foot-tall Wahoo is currently on display at the Cleveland History Center.

One player who impressively emerged during this period was Rocky Colavito, a brash young outfielder who slugged his way into the hearts of Cleveland baseball fans. In his second full season in 1958, he crushed 41 homers, followed the next year with an AL-high 42, including four in one game—making him only the third major leaguer to accomplish that feat. But on the eve of the 1960 campaign, Colavito was traded to the Detroit Tigers for Harvey Kuenn, who batted .353 the previous season. “Hamburger for steak,” bragged Cleveland GM (and Greenberg replacement) Frank Lane about the trade, referring to Kuenn as the steak. Or slop, if you listened to Indians fans who bristled over Kuenn hitting a powerless (nine homers) .308 in his one and only season with the Indians, while Colavito continued to crush it with the Tigers. Stung by the loss of their matinee idol, the fans directed their ire toward Lane, who had developed a ceaseless penchant for trades—including dealing away a young Roger Maris in 1958 and, most ludicrously, his manager (Joe Gordon) for another (the Tigers’ Jimmy Dykes) in 1960. After that year, Cleveland ownership in sync with the fans had it with Lane and fired him.

The departure of Colavito, who really rubbed it in during a 1962 game at Cleveland by bashing three homers against his former mates, began a long, dark period at Municipal Stadium that essentially lasted to the end of the Indians’ run at the venue. Over the next 30 years, they would rarely draw over a million fans and never figured in a pennant race. Long-suffering Cleveland baseball supporters pointed to the Colavito trade as the demon seed of a genuine curse, one that disabled the Indians/Guardians from reobtaining world-title status for over three quarters of a century.

By the early 1960s, the question increasingly became not whether the Indians would contend for a World Series, but whether they’d even be in Cleveland the following year, as the rumor mill churned out one speculation after another on a possible exit from Municipal Stadium and Ohio; the Indians were headed to Minnesota, or San Diego, or Louisville, or anywhere but Cleveland. In 1964, rumor became fact when the Indians admitted into looking at relocating—taking it as far as a vote from the team’s Board of Directors, which ultimately said nah, we’ll stay put. In turn, the team signed a new 10-year lease at Municipal—but with an opt-out for any year, on 90 days’ notice.

After Cleveland Browns owner Art Modell bought Municipal Stadium from the city in 1973, one of the first things he did was add 108 suites under the upper deck. Shown here is the interior for one of them. (Cleveland Memory Project—Cleveland State University, Michael Schwartz Library, Special Collections)

Resistance to Rehab.

To keep the Indians happy at Municipal, the City of Cleveland in 1966 issued $3.375 million in bonds for long-overdue repairs and upgrades to the stadium. Among the more high-profile enhancements were the addition of 1,100 new seats around the infield, expanded dugouts equipped with heating systems, and a ‘Stadium Club’ restaurant/bar with two large TV screens and seating for 300.

Intended improvements did not bring progress. New lighting did not keep the players’ union from filing grievances because too many of the bulbs were burning out. Improved restrooms didn’t keep the office of Indians GM Phil Seghi—located under one of them—from being flooded by a back-up of toilets. A new drainage system and the presence of groundskeeper Emil Bossard and sons—considered among the best in the business—failed to end the stadium’s reputation for having one of the worst playing fields. A massive, new $1.5 million scoreboard, unveiled in 1977, kept breaking down. Shatter-proof glass placed in front of a restored, enlarged press box failed to live up to its claim when, in 1983, the California Angels’ Bobby Grich broke through it with foul balls on back-to-back pitches.

Part of Cleveland’s $3.375 million upgrade for Municipal Stadium in the late 1960s included the addition of a Stadium Club, the bar from which is shown here. (Cleveland Memory Project—Cleveland State University, Michael Schwartz Library, Special Collections)

Municipal Stadium’s apparent resistance to physical rehab led to, by the early 1970s, renewed talk of the Indians’ departure—not so much to another city, but to a new venue within the area, though then-owner Vernon Stouffer had one wild thought of splitting his team’s home games between Cleveland and New Orleans. One domed stadium concept after another was raised and ultimately razed; the city was just about out of moves by 1973 when it happily ceded ownership of the stadium to Art Modell, who had purchased the Browns back in 1961.

Running Municipal under the name of Cleveland Stadium Corporation, Modell would pay only a yearly rent of a dollar on behalf of the Browns, but was responsible for continued upkeep on the stadium—a duty for which he’d be criticized for dragging his feet on. Modell did construct 108 suites under the upper deck, which he would accrue all the revenue from; the Indians wouldn’t get a dime of it, despite the fact that the suites were used during their games. Modell retained his own suite on top of the upper deck, adjacent to a TV booth; it was virtual tradition to have the camera catch his dejected demeanor as he left the suite after another tough Browns loss—particularly the team’s heartbreaking playoff exits of the 1980s. Those included the infamous “Red Right 88” call in 1980, when Brian Sipe threw an interception into the end zone when all they needed was a last-minute field goal to defeat the Oakland Raiders, or “The Drive,” the legendary 98-yard thrust by John Elway and the Broncos to score the winning touchdown in the 1986 AFC Championship game.

The Texas Rangers’ Jeff Burroughs (center) links with teammates to form a defensive barrier from riotous fans who got too drunk on 10-Cent Beer Night, the infamous promotion on June 4, 1974 that led to a forfeit loss for the Indians before a Municipal Stadium crowd of 25,000. (Cleveland Memory Project—Cleveland State University, Michael Schwartz Library, Special Collections)

Tales of Terror and Errors.

While fans and members of the media derisively tagged Municipal Stadium as “The Mistake by the Lake,” that could have easily applied to the city as a whole during the 1970s and 1980s. Cleveland’s population dropped to nearly half its 1930 peak while poverty levels shot up to nearly half of those who remained. The city defaulted on its loans, the school system went broke, and the Cuyahoga River famously caught fire.

The only thing that seemed to be flourishing in the area was crime. A group of players in town for the 1981 All-Star Game, after enjoying a nice dinner, came outside to discover that their rental cars had been stolen. Hall-of-Fame pitcher Don Drysdale, doing broadcast work for the Chicago White Sox in 1982, was mugged and robbed in downtown. Most tragically, Luke Easter, star Indians slugger of the 1950s who hit Municipal Stadium’s longest home run (477 feet), was robbed and shot to death in 1979 in the adjacent suburb of Euclid.

Municipal Stadium’s rotting reputation aligned with that of the Indians during the team’s last two decades of tenancy at the venue. While there were fond moments to embrace—Frank Robinson’s 1975 debut as MLB’s first black manager, Len Barker’s perfect game in 1981, Duane Kuiper’s one and only career home run in 1977—they were greatly outweighed by the sheer tales of embarrassment that saturated the franchise, like the ill-fated presence of pitcher Wayne Garland as baseball’s first big free-agent bust, and a 1987 team so promising that Sports Illustrated picked it to win the AL pennant—only to see it lose 101 games instead. Year after year, the losing—much like the decaying state of Municipal Stadium—remained a bitter, stubborn constant.

The few fans showing up to Municipal did the Indians no favor, either—most notoriously on June 4, 1974, when 10-Cent Beer Night brought out a crowd of 25,000 which got drunk on the cheap suds and stormed the field, threatening members of the opposing Texas Rangers. But there was also a moment three months later when a group of Municipal fans viciously heckled Milwaukee Brewers catcher Darrell Porter to the point that he charged into the stands for a physical rebuttal. Even team officials got into it the act; during a 1978 game, Cleveland GM Phil Seghi, irate over balls-and-strikes calls, began a long-distance riding of home plate umpire Joe Brinkman all the way from his booth next to the press box. It was loud enough that Brinkman stopped the game, turned toward Seghi and told him to shut the hell up.

During these dubious times, a crop of characters on the side added charm to the Indians’ defeatist ways.

One day in August 1973, a young man named John Adams bought a brass drum, brought it with him into Municipal Stadium, sat in the back of the bleachers and began pounding away. He wouldn’t stop for another 45 years, continuing to drum away well after the team moved into Jacobs (Progressive) Field. Referred to as “Big Chief Boom-Boom” by team broadcaster Herb Score, Adams became a signature presence at Indians games; he even met his future wife there.

Proving further that the bleachers weren’t for men only, Municipal Stadium had a spokeswoman for a group of not-for-the-faint-of-heart bleacher bums who managed to be well heard, even with those section of seats situated so far behind the outfield. Linda Bykowski told the Cleveland Plain Dealer that the group “perfected the art of razzing” and, being equal opportunity verbal abusers, saved some of their vocal wrath for Cleveland players. “(Indians right fielder) Cory Snyder used to get real upset,” she recalled.

Adding a fleeting touch of high-end culture to the scene, the Indians and their fans found a rabbit’s foot in Rocco Scotti, a larger-than-life operatic tenor who frequently sang the National Anthem at Municipal from 1974 to its final Indians game, averaging up to 50 appearances a year. The team slotted him to perform the Star-Spangled Banner at the 1981 All-Star Game—the fourth held at Municipal—but MLB commissioner Bowie Kuhn overruled, stating he wanted someone with more national prestige to perform. The fans revolted with such volume that Kuhn relented. Not only did Scotti sing the anthem at that game—delayed four weeks by that year’s midseason players’ strike—but also at a Strat-o-Matic version of the game played on the originally scheduled date as players remained on the picket line. A crowd estimated at 60 showed up at Municipal to hear Scotti sing and watch the board game in action—with Bob Feller rolling the “first dice.”

Municipal Stadium as seen from the distant reaches of the upper deck behind right field. Steel posts provided unwanted obstruction for fans sitting in the back rows of both decks. (Jerry Reuss)

At Last, a Savior.

Part of the problem with the Indians’ annual failure to launch was the merry-go-round cycle of ownership; from Bill Veeck’s short reign onward, the team averaged a new owner every four years or so. The list of lords didn’t include Cleveland-raised George Steinbrenner, who came to within a phone call of buying the team in 1972 before pursuing bigger dreams with the Yankees; Donald Trump, whose attempt to buy the club in 1983 was rebuffed when current ownership worried he’d move the team to New Jersey (Trump later denied the offer, which meant it was probably true); and Rachel Phelps, the fictional, bitchy owner from Major League who plotted to trash the Cleveland roster and make it easier to move the franchise. (Had she existed in real life, she might had gotten her way as there would have been no Jake Taylor, Pedro Cerrano or Ricky Vaughn to foil her scheme.)

In 1986, the Indians finally landed an owner who truly aspired to resurrect the franchise and, just as importantly, get a brand spanking new ballyard built for the team.

Richard Jacobs ultimately succeeded on both fronts. On the new ballpark front, he had both the backing of a city eager for a cultural restart, and political connections—namely his son, an Ohio state representative who was working to get funding for new sports facilities in Cleveland. With the roster, the Indians under Jacobs developed a strong new cast of talent including slugger Albert Belle, second baseman Carlos Baerga and speedy outfielder Kenny Lofton. The unveiling of Jacobs Field in 1994 only seduced more star players to join the ballclub, leading to five straight AL postseason appearances—and two AL pennants—in the late 1990s.

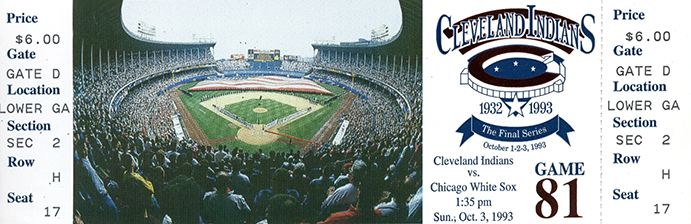

The optimism Jacobs fueled into the city and its fan base, paired with the coming new ballpark, loosened Indians fans into attending games at Municipal Stadium with an increased sense of nostalgia. In the team’s last year at the old warhorse, over two million fans passed through the turnstiles for the first time since the Bill Veeck years—even as the young but promising lineup failed to reach .500 in the standings. For the final home series, it became purely about the past, as crowds of 72,000-plus gave a last nod to the Indians’ home of the previous 60 years. Not that it would be missed; there likely were just as many utterances of “good riddance” as Thanks for the Memories, formally sung after the final home game at the stadium by legendary comedian Bob Hope, a minority investor in the franchise for 40 years.

Ticket for the final baseball game at Municipal Stadium on October 3, 1993. After the Indians’ departure, the stadium remained active for two more years before Browns owner Art Modell jolted the city by packing up and bolting to Baltimore.

Alas, a Villain.

With the Indians’ departure to Jacobs Field, Art Modell had Municipal Stadium—which he still owned—all to himself and his Browns. He had the opportunity to be part of Cleveland’s new sports facility wave of the 1990s, which yielded Jacobs Field and the adjacent Gund Arena (home to basketball’s Cavaliers), but he declined—preferring to jumpstart Municipal with the extension of an existing “sin tax” the city was planning for funding on stadium improvements.

Modell’s foresight would prove to be as shallow as his loyalty to generations of rabid Browns supporters. As he witnessed the smashing onset of Jacob and Gund both at the box office and on the playing surface, Modell realized the mistake he’d made in turning down a piece of the downtown sports pie. Rather than play the fool, he played the victim, claiming he was left out. So he set about moving out of Municipal—and Cleveland.

On November 6, 1995, 67 years to the day that Clevelanders voted for Municipal Stadium to be built, Modell signed its death warrant. He announced that he was moving the Browns to Baltimore, capping secret discussions that had been taking place for three months with Maryland officials. Cleveland went into shock, as its citizens—either in defiance or denial—still voted for the sin tax extension the very next day. Voicing their disgust in print, the Cleveland Plain Dealer wrote of Modell, suddenly the most hated man in town: “When ordinary people throw a tantrum, they break dishes or put their fists through a wall. When a millionaire does it, especially while blaming others for his pitiful plight, he breaks a city’s heart.”

Six weeks after Modell’s sucker punch, Municipal Stadium held its very last event with the Browns defeating the Cincinnati Bengals, 26-10. Fans in the Dawg Pound began ripping out their bleacher seats and, rather than keep them as mementos, threw them out in the field. It was one last, big middle finger directed at Modell, who wisely stayed far away from the stadium that day.

Municipal Stadium’s final year of existence, in 1996, was much like its first—alone with no tenants. The only activity it got came in November when Osborn Engineering, which was paid to build the facility in 1930, got paid again to tear it down. As deconstruction continued into the Spring of 1997, one wonders if the Indians’ 1949 pennant hopes, buried behind the outfield fence in one of Bill Veeck’s more memorable publicity stunts, were unearthed. A good chunk of Municipal’s resulting debris—10,000 cubic yards’ worth—went to sleep with the fishes at the bottom of Lake Erie, placed there to form a series of artificial reefs.

The $154 million in voter-approved sin tax funding, initially intended to spruce up Municipal Stadium, was redirected toward its demolition—and its replacement, Cleveland Browns Stadium, completed in 1999 as essentially a football-only venue. Its primary tenant would be a resurrected Browns team, which officially was not an expansion franchise—though it really was; it inherited the old Browns’ brand and history, as if it had taken a three-year break, per the settlement of a lawsuit filed by Cleveland against Modell. The new, ‘old’ Browns struggled out of their ‘slumber,’ just like an expansion team—winning five of their first 32 games and finishing last in 15 of their first 19 seasons, including a 0-16 mark in 2017. Meanwhile, Modell’s Browns, officially listed as an expansion team called the Baltimore Ravens—though it really wasn’t—would need only five seasons in Maryland to win its first Super Bowl.

Epilogue.

The all-time leaders among major league ballplayers at Cleveland Municipal Stadium are full of trivia that would stump even the most educated of historians. Pacing the stadium in career hits with 606 was not Earl Averill or Larry Doby, but Bobby Avila, the solid supporting cast member of the 1950s Indians. Bashing the most home runs with 119 was not Rocky Colavito or Al Rosen, but Andre Thornton, he of Cleveland’s forgettable years during the 1970s and 1980s. (Thornton also had the most RBIs, with 427.) Collecting the most triples with 28 were not any of the early star players (Averill, Lou Boudreau, Joe Vosmik) who took advantage of Municipal’s spacious outfield dimensions, but Brett Butler—the prototypical leadoff spark who featured for Cleveland from 1984-87. Finally, the highest career batting average in Municipal Stadium annals (minimum 500 at-bats) was Carlos Baerga, who posted a .322 mark as part of the last group of players to inhabit the venue before the team’s move to Jacobs Field.

Long-time Clevelanders don’t miss Municipal Stadium, but they do acknowledge its importance as a civic beacon that welcomed crowds both massive and minute into its voluminous edifice. The Plain Dealer’s Bill Livingston summed up the locals’ reconciling of Municipal, calling it “big, cold, majestic and truthfully ugly—but it was ours.”

In the end, Municipal Stadium could be best summed up by architectural critic Paul Goldberger, from his book Ballpark: “A planning process intended to enhance Cleveland’s civic grandeur ended up, paradoxically, creating one of the least urban of city baseball parks—an isolated, bleak structure remembered for its harsh winds blowing off the lake than for anything it might have done to elevate Cleveland as a city.”

“It may have been in the city, but it was not of the city.”

The Ballparks: League Park Rustic, tight and beloved with its cozy sightlines, unpredictable right field wall and a myriad of memorable moments, League Park lived to become the ballyard that wouldn’t go away. Not that anyone complained, as Clevelanders developed a soft spot for the little fellow that has stood the test of time and survived in one form or another all the way to the present day.

The Ballparks: League Park Rustic, tight and beloved with its cozy sightlines, unpredictable right field wall and a myriad of memorable moments, League Park lived to become the ballyard that wouldn’t go away. Not that anyone complained, as Clevelanders developed a soft spot for the little fellow that has stood the test of time and survived in one form or another all the way to the present day.

The Ballparks: Progressive Field The Cleveland Indians once played at Municipal Stadium, an aging monstrosity often referred to as the “Mistake by the Lake.” Those few who showed up to watch the Tribe saw them as clueless yet lovable losers. But when Jacobs (later Progressive) Field opened in 1994, not only did the Indians’ fortunes turn in a positive direction, so did the psyche of Clevelanders. Not a bad turnaround for a city once laughingly looked upon by outsiders as a decayed, national joke.

The Ballparks: Progressive Field The Cleveland Indians once played at Municipal Stadium, an aging monstrosity often referred to as the “Mistake by the Lake.” Those few who showed up to watch the Tribe saw them as clueless yet lovable losers. But when Jacobs (later Progressive) Field opened in 1994, not only did the Indians’ fortunes turn in a positive direction, so did the psyche of Clevelanders. Not a bad turnaround for a city once laughingly looked upon by outsiders as a decayed, national joke.

Cleveland Indians Team History A decade-by-decade history of the Indians, the ballparks they’ve played in, and the four people who are on the franchise’s Mount Rushmore.