THE BALLPARKS

Progressive Field

Cleveland, Ohio

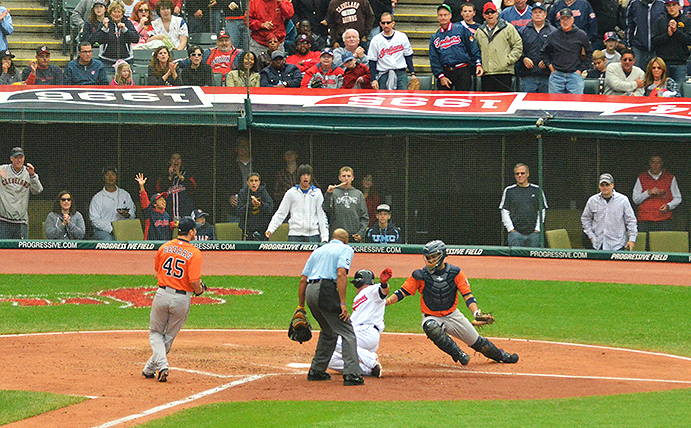

(Wikimedia—Paul M. Smith)

The Cleveland Indians once played at Municipal Stadium, an aging monstrosity often referred to as the “Mistake by the Lake.” Those few who showed up to watch the Tribe saw them as clueless yet lovable losers. But when Jacobs (later Progressive) Field opened in 1994, not only did the Indians’ fortunes turn in a positive direction, so did the psyche of Clevelanders. Not a bad turnaround for a city once laughingly looked upon by outsiders as a decayed, national joke.

Happiness is a ballpark, one that brings smiles to people in a city where smiles were once an endangered species, where grins were cast only out of painful sarcasm.

Happiness is a ballpark, one that brings smiles to people in a city where smiles were once an endangered species, where grins were cast only out of painful sarcasm.

While Progressive Field is not exactly the lone knight in white steel armor that saved all of Cleveland from ruin, it has helped to revive a vibe to a city that was dying a smoky, rust-tinged death. The spunky home of the Indians invites fans to behold a downtown skyline that exhibits more pride, even if the venue doesn’t wholly integrate within it. Fans driving in from the suburbs exit the Interstates and instantly and literally find themselves at the lap of the ballpark, with its mix of stone, brick, and white, steely matrix influenced by the area’s bridges exposed for all to see. To the north, those who disembark from public transit at Cleveland’s iconic Transit Tower can walk a few blocks to Progressive Field and rarely touch the ground, traversing through an elevated mall-like passage and pedestrian street bridges. That may be unnerving for the many local bars and eateries who fear the bypassing of 81 games’ worth of foot traffic, but it seems the fans ultimately find their way there.

Indians fans still lovingly refer to Progressive Field as The Jake, the shorthand title for its original name of Jacobs Field. “The Prog” doesn’t quite make it; that sounds more like an ode to Yes, Rush and Genesis at the nearby Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. Flo’s Place? Jamie’s Hangout? No and no.

Progressive Field’s more devout regulars include Ron Ochmann, “The Mayor of Section 164,” who bought season tickets for himself and his wife to The Jake’s inaugural 1994 campaign. When she passed away in 1998, Ochmann continued to renew not only his seat but hers, typically leaving it unoccupied as he aged into his 90s. Then there’s the ballpark’s loudest fan, John Adams, who literally drums up support with a 26-inch bass drum from the top row of the left-field bleachers whenever the Indians are threatening to score or lock down a victory. Adams, who initially scoffed at The Jake as “segregationist”—“People with money don’t have to sit with people without money,” he complained back in 1994—has, along with Ochmann, come to admit that Progressive Field has become their home, a far cry from the Indians’ previous residence in more medieval times for Cleveland. They should know. They were there.

Dark City (Except When on Fire).

Cleveland’s postwar years were industrial boom times, and the Indians benefitted. The team moved from cozy but rotting League Park to the massive, city-built Municipal Stadium along the shores of Lake Erie, and in 1948 they set a then-major league attendance mark of 2.6 million—winning an American League pennant along the way. That’s as good as it got, for a long time to come, for both the Indians and the city.

In 1950, Cleveland’s population was at 914,000. By 1970, it was down to 750,000—and then it went down by another third over the next 20 years, to 500,000. The birth of the Environmental Protection Agency came too late to rescue the Cuyahoga River, which actually caught fire in the 1970s from industrial waste. Perhaps to show solidarity, mayor Ralph Perk had his hair catch fire from flying sparks at a ribbon-cutting ceremony. Downtown became dark, desolate and dangerous at night, which is probably why the producers of Howard the Duck decided to pick a dumpster in a Cleveland alley as a landing spot for the title character after his involuntary journey through space. There was no money to go around; even the city’s public school system went broke. It seemed that the only growth taking place in town was poverty and crime. “Cleveland,” wrote the Cleveland Plain Dealer’s Dick Feagler, “is the one city in the universe where pain is unavoidable.”

As Cleveland went, so went the Indians. A respectable team loaded with ace pitchers during the 1950s, the wheels fell off with the trade of highly popular slugger Rocky Colavito in 1959. At that point, the Indians had suffered just six losing seasons in 31 previous years; over the next 34 years, they would only produce six winning seasons.

The Indians became a joke, much of it self-inflicted. In 1974, they decided it was a good idea to try 10-Cent Beer Night, which led to a lot of drunk fans and a game-ending riot. Over a decade later, when the Indians’ roster looked promising to the point that Sports Illustrated picked them to win the pennant, the team embarrassed the magazine—and themselves—by losing 101 games. Municipal Stadium was getting older, colder and more deserted, and at one point the Indians even considered splitting their home schedule between the monstrous 80,000-seat facility and the New Orleans Superdome, 1,000 miles to the south.

By 1980, Cleveland politicians and business leaders woke up and realized that smokestacks were not the wave of the future. They came up with Cleveland Tomorrow, a consensus group to lay out the future for a revived downtown. Over the next 10 years, the fruits of their labor would yield the city a substantial makeover, with a $400 million renovation of Terminal Tower, a refreshed entertainment district (Playhouse Square), new downtown malls and the creation of the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. But the path to a new Indians ballpark would be, to quote Rock HOF inductee Paul McCartney, a long and winding road.

Progressive Field’s 19 light standards remind many of toothbrushes, but they were designed to mimic Cleveland’s age-old smokestacks. (iStock)

The Jake Effect.

The first idea was to build a domed, multi-purpose stadium for the Indians and the NFL’s Cleveland Browns with 100% public funding. Locals liked the concept—until they found out that a hike in property taxes would fund it. They thus slaughtered it at the ballot booth by a 2-1 margin in May 1984. On the heels of that defeat, another domed concept was put together by Cleveland architect Robert Corna, who drew up a six-sided facility called the Hexagon. Corna got political backing from Ohio state representative Jeff Jacobs, and enough money was raised to buy land at the proposed stadium site at the south end of downtown—at one time a thriving, go-to hub called the Central Market, but now little more than a sea of street-level parking lots. Ultimately, the Hexagon also died when the Browns decided they would rather stay put at Municipal Stadium, which they owned and paid an annual rent of one dollar.

In 1986, the Indians had new ownership; curiously enough, the new Lords consisted of Cleveland commercial property king Richard Jacobs—who just happened to be Jeff Jacobs’ father—and his brother David. The hunt for a new Indians ballpark now became a family affair, as Richard insisted he wanted out of Municipal Stadium and eyed the land his son had helped secure. He even convinced the city and county that a sin tax on alcohol and tobacco—which his son had proposed as the Hexagon’s method of financing—would be the way to go. There was one thing Jacobs didn’t want in a new home for the Indians: A co-tenant. Cuyahoga County officials agreed, and in 1990 put forth a new initiative for building a sports complex that would include an Indians ballpark and an adjacent arena for the NBA’s Cleveland Cavaliers, who had abandoned the city—and, just as importantly, the county—in 1974 to move to a suburban facility 20 miles to the south in Richfield.

Baseball fans were worried that another failure at the voting booth would be the death knell for Cleveland baseball. They were spooked when one of Jacobs’ first acts as owner was to ditch the “C” on the caps in favor of the nostalgic (and increasingly controversial) Chief Wahoo icon, shedding any city identification. Commissioner Fay Vincent didn’t add comfort when he came to town during the ballpark campaign and warned that failure to pass the initiative would leave Clevelanders “confronting a subject that we want to avoid.”

On the six-year anniversary of the defeat of the first domed stadium project, history would not repeat itself. Barely. Issue 2, as the ballpark/arena initiative would be named on the ballot, passed with 51.7% approval among county voters. The change of heart was perhaps partly based on the Indians’ pledge to fund half of the ballpark’s cost, and perhaps partly based on the sin tax raised to pay the rest. But voters outside of Cleveland helped carry the vote; people within city limits opted more on the no side, fearing that too many dollars would be spent on fancy downtown redevelopment and not on some of the city’s more financially troubled departments, such as education.

Gate A, behind the left-field corner, allows fans on the outside to get a limited view of the action just by peering through the gates. (iStock)

Understand the Building.

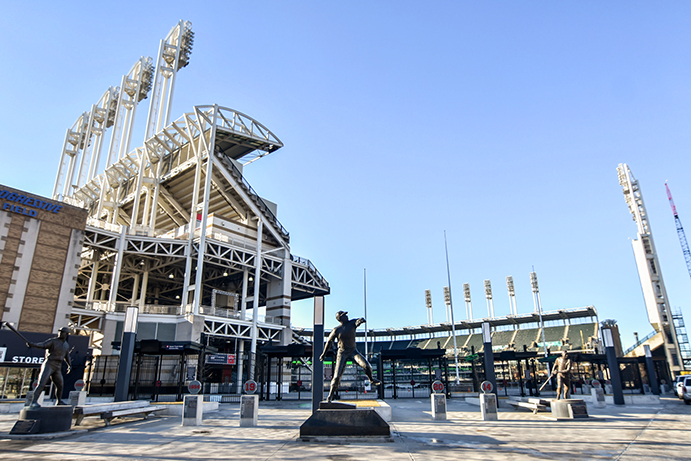

For Joe Spear, the lead architect for Kansas City-based HOK Sport (now Populous) hired to design Progressive Field, first impressions made all the difference in conceptualizing the ballpark’s look. Standing at the corner of Carnegie and Ontario where the venue’s front gate would soon look over, Spear glanced around and quickly noticed all the bridges spanning over the Cuyahoga, which snaked to the west of downtown. “I counted 12 different bridges. Lift bridges, drawbridges, bridges that are just beautiful structures,” he told Sports Illustrated years later. “We wanted the structure of the ballpark to be very expressive and understandable like a bridge, with no cladding, no windows.”

What Spear and HOK would deliver would indeed be an exterior highly exposed with white steel columns, trusses and cross bracing, an industrial skeleton masking the ballpark’s structural core. “A guy on the street can look at a bridge and see how it is held up,” Spear said. “We wanted the structure to be a major architectural component and help you understand the building.”

Offsetting the matrix of steel is a combination of Atlantic green granite interrupted by horizontal strips of Kasota sandstone, occasionally topped by golden buff brick—all classical elements of surrounding Cleveland buildings, most notably the West Side Market across the Cuyahoga. The mix of brick, stone and granite is used as bulky bases shaped as truncated square pyramids for the outer, rounded steel supports, and more prominently as taller, square structures which appear randomly but strategically so as to hide external spectator staircases and ramps. It’s also a more prominent feature of the Indians’ front office, a rectangular, four-story building that juts away from the ballpark bowl near the left-field corner and is topped by an arced tin roof that appears to float above it, held aloft by more elements of white steel.

Structurally, one of Progressive Field’s most oft-mentioned elements are the 19 vertical light towers that rise high above the upper deck. Spectators often compare them to toothbrushes, but they were actually designed as a tribute to the area’s smokestacks.

Inside, Progressive Field opens up northward to a view of downtown Cleveland, though a massive scoreboard—currently the majors’ largest, at 13,000 square feet—perched behind the single-decked, left-field bleachers does provide a bit of blockage. The reward for those sitting further up, particularly in the upper level near the right-field corner, is that you get a better view of the skyline and maybe even Lake Erie, for all it’s worth. The downtown view led many to believe that the Indians and HOK were attempting to Xerox the success of Baltimore’s Oriole Park at Camden Yards, completed two years before Progressive Field. But nobody was complaining; fans across the major league landscape were thirsting for an about-face from the cold, enclosed, multi-purposed stadia of the previous 25 years, and wanted something more intimate and connective to the surrounding environments. Progressive Field would be among the first of the responses, following immediately in the footsteps of the wildly popular Oriole Park. Still, the Indians were weary of coming off as imitating the Baltimore blueprint. “I didn’t want something out of a file drawer,” remarked Richard Jacobs, “I wanted to start with a clean piece of paper.”

Though Oriole Park was wholly praised for its retro originality, it actually borrowed from Progressive Field in one respect. Most of the seats down the lines at Camden Yards were tilted to face closer to the infield, so fans didn’t have to turn their necks while the rest of their bodies were forcibly aimed toward the outfield. The idea was originally Cleveland’s, and quickly picked up by the Orioles as a late directive to their architects—which also happened to be HOK.

Progressive Field would develop enough character to differentiate itself from Oriole Park, though it did pay homages to other ballparks. Its steep bleachers in left field are reminiscent of Chicago’s Wrigley Field, while the wall they stand behind, at 19 feet tall, is a nod toward Fenway Park’s famed Green Monster in Boston. The wall, with an out-of-town scoreboard imbedded within it, was an initial source of disdain for Indians hitters who felt it would lean Progressive Field toward becoming a pitcher-friendly ballpark. But the overall field dimensions, asymmetrical and straight with three bends, would pacify them, with nine-foot walls elsewhere, a modest 325 feet down each line and no more than 375 feet to each power alley. And right fielders fearing competition with fans trying to nab a home run ball off the top of the wall would be content to know that a flat, six-foot buffer would separate the wall from the first row of bleachers.

The most coveted of all of Progressive Field’s suites are the 10 located at ground level between the dugouts. They’re closer to home plate than the pitching mound. (Flickr—Erik Drost)

The Suite Smell of Class Separation.

Adding uniqueness to Progressive Field was the make-up of its seating levels—leading to some of the venue’s bigger criticisms regarding a clear separation of haves and have-nots. The field level is normal enough—and close to the action—but above is where the quibbling begins. On the third-base side, three levels of luxury boxes dominate, flanked in the left-field corner by a series of jagged, glass-encased extensions that make up the spacious, two-story Terrace Club. Over on the first-base side, only the upper third of the luxury boxes continues unabated. Sticking out below is a middle tier of seating, which at first glance looks like 12 sections of ordinary seating. But there is a higher price to pay for what is called the Club Level—though you can get your money’s worth with a hearty appetite behind these seats with an expansive, exclusive lounge full of food and non-alcoholic drinks that comes gratis with a ticket. (Alcohol is never free, nor even 10 cents a cup as it once was at Municipal Stadium.) The Club Lounge is the reason for Progressive Field’s most disparate exterior feature with floor-to-ceiling glass—countering Joe Spear’s initial brag that there would be no windows on the outside.

Perhaps the most valued suites within Progressive Field are practically hidden away at field level. Between the two dugouts behind home plate, 10 suites are situated that include swivel-chair seating for 12 and a backstage living area that includes the usual creature comforts of the suite life. Just one of two ballparks to offer up such seats (Angel Stadium of Anaheim is the other), the Dugout Suites were considered so premium by the Indians that they initially had buyers pay up $100,000 per year as part of a 10-year lease—with all $1 million over the life of the pact to be paid in advance. The sales generated one of the rare bits of controversy during the ballpark’s construction when Blue Cross & Blue Shield of Ohio snapped up one of the suites—upsetting those who felt its $1 million should have been better spent on reducing patient coverage costs.

Beyond the suites, the Indians were also hoping to secure up-front revenue to help pay off their end of construction costs by securing a naming rights agreement with an outside sponsor. For a brief time just months before the ballpark’s opening, it appeared the ballpark would be named Society Field after a locally-based bank, but the deal fell apart amid a merger with KeyBank. Still without a paid-for name at the eleventh hour—the Indians were ready to just go with Gateway Park—Richard Jacobs, who had taken full control of the Indians since the death of his brother David in 1992, decided he’d pay to put his own name on the building. For $13.9 million, the new ballpark officially became Jacobs Field.

Cleveland Rocks.

It had been 57 years since the City of Cleveland had built a major sports facility, so it’s easy to understand how eager the locals were to check out The Jake. Three full months before the first pitch at the new ballpark, a million tickets had already been sold for the Indians’ inaugural season, and season ticket sales were up six-fold from the year before. Enthusiasm was sky-high; the Indians were even able to snare President Bill Clinton out of the White House to throw the ceremonial first pitch on Opening Day—though Clinton, out of political correctness, insisted that he don Cleveland’s “C” cap rather than the Chief Wahoo version the players were wearing. While the sellout crowd of 41,459 quickly warmed up to The Jake, the Indians’ bats took a little longer as opposing Seattle pitcher Randy Johnson kept the Tribe hitless through seven innings. But the future Hall of Famer faltered in the eighth, allowing the Indians to tie the game at 2-2; into overtime, both teams traded a run in the 10th and, a frame later, Wayne Kirby capped a rally with a run-scoring single to give Cleveland the inaugural home victory, 4-3.

The win was nice for Clevelanders, but Jacobs Field was the bigger triumph of the day. “(The Indians) built the future, ditched the past, and created one hell of a present,” wrote Bruce Jenkins of the San Francisco Chronicle. Mike Lupica of the New York Daily News penned that the ballpark was “like the pearl you hope to find inside of an oyster: beautiful and full of grandeur.” Longtime Indians sportswriter Terry Pluto would later reflect the feelings of Clevelanders on The Jake’s opening, after so many years tolerating Municipal Stadium: “I suddenly felt like, ‘This is what it was like in America when the lights came on and indoor plumbing showed up.’” Indians players and coaches were just as pleasantly thrilled with the quantum leap between Municipal and The Jake, salivating over a clubhouse four times bigger—even the bat boys got their own locker—along with a spacious weight room and several batting cages. “We really think we’ve done one major thing—change an attitude,” said Bob DiBiasio, the Indians vice president of public relations, to the Cleveland Plain Dealer. “Today marks the beginning of a new era of Indians baseball.”

Mirroring their Opening Day performance, the Indians took a while to crank it into high gear at Jacobs Field—and once they did, it was overdrive all the way into the next century as the team and its fans flushed three-plus decades of Cleveland baseball misery out of their system.

After losing seven of their first 12 games at The Jake, the Indians suddenly got red-hot and won 18 straight at home. They got used to their new home in more than ways than one could have imagined. By midseason, opposing teams discovered that the Indians had a camera positioned in center field looking back toward home plate, linked to a monitor been set up behind the Cleveland dugout as a possible way to steal signs; Major League Baseball investigated and told the Indians to shut everything off. More famously, Indians reliever Jason Grimsley really got to know his way around The Jake during a July game when, after umpires confiscated an alleged cork-filled bat from Cleveland slugger Albert Belle, he crawled through an air vent into the umpires’ dressing room and replaced the bat—which indeed did contain cork—with a legit replacement. Once the umpires returned to their room, it didn’t take long for them to smell a rat, stepping over cracked ceiling tiles and noticing a bat that, suddenly, had the signature of Belle’s teammate Paul Sorrento. Belle was suspended seven games; Grimsley didn’t publicly confess to his stunt until four years later.

Progressive Field’s steep left-field bleachers, reminiscent of Chicago’s Wrigley Field, elevate from behind a 19-foot wall that some compare to Boston’s Green Monster at Fenway Park.

The Indians were on their way to making the postseason for the first time in 40 years and shattering the franchise’s season attendance mark (on pace for over three million) in 1994, but the parade was heavily rained upon by big league owners who insisted on a salary cap—and a players’ union that angrily refused, leading to baseball’s most catastrophic work stoppage. The regular season was halted in mid-August, never to restart; the playoffs, World Series, and the first few weeks of the following season were all wiped away, until future Supreme Court justice Sonia Sotomayor ordered everyone back to work—salary cap or no.

The work stoppage crippled baseball’s relationship with its fans in most major league cities—but not in Cleveland. When the players returned in 1995, Indians fans were ready to pack The Jake all over again. And again. And again. On June 12, 1995, the Indians sold out the ballpark for a game against Baltimore; it would be another five years and 455 home games before another seat was left unsold. The ballpark had much to do with it, but so did the performance of the Tribe.

In 1995, the Indians won 100 games with just 44 losses in a strike-shortened campaign, taking their first American League pennant since 1954 before losing the World Series in six games to Atlanta. Two years later, Cleveland returned to the Fall Classic and came even closer to securing a world title, falling short with an extra-innings, Game Seven loss to an upstart Florida Marlins squad. It was soon pointed out that in just four short years, the Indians had already hosted more World Series games at The Jake than they had in 60-plus years of play at Municipal Stadium. “Jacobs Field, Era of Champions,” the outfield wall displayed at the ballpark.

The Indians were not only good—winning five straight AL Central division titles from 1995-99—they were simply fun to watch. Its roster was a rich collection of rising stars (Jim Thome, Manny Ramirez, Bartolo Colon), fast, Gold Glove-worthy talents (Kenny Lofton, Omar Vizquel) and reliable star veterans (Eddie Murray, Orel Hershiser, Jack Morris). They all made Jacobs Field come alive, and vice versa. Though The Jake was slowly evolving into a park that oh-so-slightly favored the pitcher, the Indians’ impressive lineup put up massive numbers to suggest otherwise. Through their first seven seasons at home, Cleveland hit a collective .294. In 1999, it became the first major league team in 49 years to score over 1,000 runs, with exactly 500 notched at The Jake. And in 2001, in one of the most memorable games played to date at the ballpark, the Indians showed that no opponent’s lead was safe when they rallied from a 14-2 deficit in the seventh to defeat Seattle in 11 innings, 15-14.

Cleveland fans were ecstatic over the Indians, understandably buying into the claim that a new ballpark could turn a team’s fortunes around. For five straight years starting in 1996, the Indians sold out every ticket before the season began. The team accommodated ticket demand by adding 480 bleacher seats in 1997—the only major adjustment during the Jacobs Era. “People had Wahoo signs in their front yards,” Orel Hershiser told Terry Pluto. “There were posters of the players in about every restaurant. It was like being in a college town.” People clung to an Indians ticket as if it was Charlie’s golden pass to Willy Wonka’s. Somewhere, the ghost of Bill Veeck—the vibrant, former Indians owner who once enticed 2.6 million fans through Municipal Stadium’s gates—must have looked at all of this and thought, “Wow.”

Richard Jacobs even made the unique move of putting the Indians on the stock market, offering public shares to fans and others who felt the team would be a hot buy. It wasn’t exactly Apple, but investors managed a decent return as the stock opened on Nasdaq at $15 per share and rose to as high as $23.

It was not all wine and roses in Cleveland during Jacobs Field’s early years. Fans did complain of the ginormous scoreboard, handsomely topped by the Indians’ script logo, ruining their view of downtown; the less-than-intimate views of the field from the upper deck, high above the three levels of luxury boxes; and the high prices charged for food and drinks, though admittedly the selection was far better than back at Municipal Stadium.

There was grumbling, too, from those who used perspective on a city patting itself on the back for a job well done when, in reality, not all was entirely well. “The problem is that Cleveland is a city with many, many problems,” Roldo Bartimole, a reporter for the city’s alternative weekly Cleveland Free Times, told the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. “When anyone ever comes in here, they go downtown and talk about the renaissance…If you go out of this mile-and-a-half area, almost within a stone’s throw, you find poverty and kids not being able to learn. What it’s done is it’s taken the attention of the community off its problems.”

Sculptures of Indians legends Jim Thome, Bob Feller and Larry Doby grace the Gate C entrance behind center field, where most fans enter into Progressive Field. (Flickr—Erik Drost)

A Tough Act to Follow.

By the end of 1999, Richard Jacobs was nearing his 75th birthday and figured he’d done all he needed in bringing the Indians into their ballpark of choice—and back to respectability. So he sold the franchise for $323 million—the highest price for a major league team to that point, and roughly ten times what he had paid for it just 14 years earlier—to Larry Dolan, a prominent Cleveland lawyer. Jacobs was thrilled to be handing the team off to another local, but Dolan sensed challenge, publicly stating that Jacobs would be “a tough act to follow.”

Dolan wasn’t kidding. The All-Star roster he inherited slowly began to spin off toward other teams via free agency. The Indians, in turn, appeared loathe to replenish with more star power, choosing to be more tenuous with the pocketbook. It showed, as the Indians’ payroll went from one of the league’s highest to one of its lowest. In Dolan’s first full season as owner, the Indians failed to make the playoffs for the first time since moving into The Jake. A year later, it took only two games for the sellout streak to end at a then-record 455; Chuck Finley, who started on the mound for the Indians that night, said the crowd of 32,763 made him think he was “playing an intrasquad game.” Another year later, the Indians suffered their first losing campaign at Jacobs Field. Overall, attendance didn’t just edge downward, it plummeted—from 3.1 million in 2001 to 1.7 million just two years later. Dolan even bought back all the stock that Jacobs had made available to the fans.

On the field, the Indians displayed a rollercoaster existence in the standings through Dolan’s first decade behind the wheel—good one year, bad the next, and so on—but the gate remained stubbornly low, unwilling to respond to the better campaigns. When the 2007 team gave Cleveland its first divisional title in six years—coming within one win of an AL pennant—only 2.2 million fans, good for 21st out of 30 MLB teams, showed up. All of this was not only bad news for the Indians, who were losing out on significant revenue, but also for the restaurants and bars that had ganged up north of the ballpark and relied on the big crowds to expand its bottom line. A good number of them had to fold tent as a result.

The Jake’s boom years of the late 1990s clearly showed that, for a good third of the fan base that showed up, the ballpark was nothing more than novelty that had worn off. The renaming of the ballpark to Progressive Field in 2008 only made it symbolically feel as if the Golden Days had fallen further behind in the rearview mirror.

The Dolan regime at first felt it didn’t need to rethink Progressive Field, sensing that the ballpark was still new and relevant enough to avoid change. Any renovations made were relatively minor and green-focused, such as replacing the scoreboard with LED lights, installing solar panels (the first AL park to do so) and improving recycling efforts. All of this pleased environmentalists and saved the Indians money, but it wasn’t necessarily a selling point to bring in more fans. But at least those who were still showing up liked the ballpark more than ever; in a 2008 Sports Illustrated nationwide fan poll that took all aspects of the ballpark experience—including atmosphere, affordability, hospitality, traffic and food—Progressive Field came out ahead of all other 29 major league venues as the best overall.

Most of the 10,000 seats removed during Progressive Field’s renovation in the mid-2010s occurred above the right-field bleachers, in favor of vacuous patio areas that come off looking like shipping containers. (Flickr—Erik Drost)

“The Unofficial Annex of the Cleveland Port Authority.”

Finally, in 2014, the Indians went full throttle into makeover mode. A two-year, $77 million effort to reduce capacity, increase demand and liven up the joint was initiated to bring more energy—and fans—back to the ballpark.

For some of Progressive Field’s more privileged ticketholders, an expansive lounge/bar behind the field level’s best seats called the Homeplate Club opened, with airy views of the action and three rows of drinking rails with chairs. While this was exclusive only to those sitting below the club, the “rest” of the fans were paid attention to with a major upgrade in the right-field section of the ballpark, which the Indians had labeled a virtual “dead” space of fan inactivity in the past. To correct that, the team expanded the Kid’s Clubhouse to two levels’ worth of games and skills challenges for the little ones, with balconies added for parents to keep one eye on the action and the other on the kids. Down on the field level behind the right-field foul pole, another playland—this one aimed at Millennials—was developed and entitled as The Corner, a reference to long-time Indians broadcaster Tom Hamilton’s first-pitch phrase, “We’re underway at the Corner of Carnegie and Ontario.” The Corner is a two-level bar and lounge that includes patio furniture, a fire pit and plenty of drinking rails; there’s even an automatic beer dispenser if you want to refill on your own (credit cards accepted).

Adjacent to The Corner, behind the right-field bleachers, is the Neighborhoods—a wonderful touch of local food flavor in which Cleveland-area restaurants are allowed to offer some of their best sellers. Perhaps the most popular—certainly the most attention-getting—item within this stylish, brick-laden food court is the Slider Dog. What’s on it, you might ask? You might be sorry to get the answer: It’s topped with bacon, mac and cheese—and Fruit Loops.

But it’s above the Neighborhoods, in Progressive Field’s upper two decks behind right field, where the ballpark’s most noticeable and awkward-looking change has taken place. The aim was to eliminate many of the seats and replace them with spacious standing areas, in the hopes of expanding the nomadic, lounge-like fan experience of The Corner below. The renderings for this reinvented area looked quite chic, with streamlined standing areas, decorative player murals and an orderly splash of Indians Navy Blue as aesthetic vertical separation. The reality was quite different; the area appears as if a series of shipping containers had been planted in the upper level, decorated with everything from ads to championship pennant graphics to retired Indians jersey numbers. (“The unofficial annex of the Cleveland Port Authority,” joked one local online rag.) These standing areas are not only unattractive on the outside, but they’re not all that engaging when you’re within one; they’re just vacant, concrete patios with nothing more than a trash can. Nevertheless, any fan can access the standing areas and hang there all game—if, for any reason, he or she wanted to.

The look from the top of Progressive Field’s upper level. Providing slight interference to the view of downtown Cleveland is the main scoreboard, the majors’ largest at over 13,000 square feet. (Flickr—Erik Drost)

Where Are You?

All of these resulting fixes—which also include the relocation of both bullpens to adjacent, cascading locations parallel to and behind the right-center field wall—reduced Progressive Field’s capacity down to 35,000, a whopping 10,000 below its 2010 max. And if the Indians were hoping that this enhanced intimacy would bring higher attendance figures as a result, they had a golden opportunity to prove it in both 2016 and 2017.

After the 2010s had begun with the team in the midst of a prolonged funk—five straight years without a winning record—the Indians brought on board Terry Francona as their new manager. The son of former Indians player Tito Francona, Terry brought with him the experience of leading the Boston Red Sox to two world titles—and he was also handed some terrific young talent in ace pitcher Corey Kluber and multi-faceted infielders Francisco Lindor and Jose Ramirez. Under Francona’s watch, the Indians immediately shifted into winning mode, and in 2016 nailed down their first divisional title in nine years, bursting their way through the AL playoffs to their third pennant in the Jacobs/Progressive Field era.

All this, and few came to the ballpark; only the lowly Oakland A’s and Tampa Bay Rays drew fewer fans, as the Indians could only muster 1.59 million through the turnstiles. It gets worse; for Game Seven of a terrific World Series at Progressive Field, with the Tribe just one win from taking it all for the first time in 68 long years, many Clevelanders decided they’d rather strike it rich and sell their tickets to visiting Chicago Cubs fans. The result was a virtual home game for the Cubs, who won a nail-biting rubber match in 10 innings, 8-7.

From their 2016 success, the Indians rightly anticipated an attendance bump for 2017—but the gains were modest, even as the team continued to improve. Easily on their way to winning a second straight divisional title, the Indians in late August began a winning streak that grew and grew, day after day. By the morning of September 12, it had reached 19 games—one shy of the AL record—with home games on tap for possible record-tying and record-breaking wins. One would have expected a massive run on available tickets, leaving Progressive Field filled to capacity to witness history. One was wrong. Only 24,000, 11,000 shy of a sellout, came to watch the Indians win #20 with a 2-0 victory over Detroit. A day later, the Tribe made it a record 21 straight with a 5-3 decision over the Tigers—and still there were 6,000 seats unsold. The weather was not to blame; game-time conditions were seasonally pleasant. Maybe, had the streak been aligned to be broken on a weekend instead of midweek, the tickets would have run out. Maybe.

The historic streak did boost the ceiling on advanced ticket sales late in the year and pushed the Indians over the 2 million mark in season attendance for the first time in nine years—but still, for a team that finished with 102 wins, placing 22nd in major league ticket sales was, in a word, embarrassing.

So what gives? Why have the Indians, who once could sell out The Jake day in and day out with ease, been constantly unable to fill the joint since? Did the ballpark’s early successes spoil Cleveland baseball fans? Have the Dolans flunked Marketing 101? Has Chief Wahoo’s politically incorrect grin turned off even the locals?

As it often does, the answer comes to this: All of the below. There’s the continued dwindling population of not only Cleveland—20% lower than when Progressive Field opened—but of Cuyahoga County as well. There’s the especially minute residential presence in downtown Cleveland itself. There’s the region’s relatively minimal corporate presence, a cash-cow source of revenue for the Indians and any other major league team. And then there’s this: Within a 50-mile radius of Progressive Field, there are four minor league ballclubs—three affiliated with the Indians, the other an independent outfit. Pro baseball has saturated the Cleveland market; perhaps it’s encouraging would-be Progressive Field spectators to go someplace where they experience admittedly inferior baseball, but at admittedly cheaper prices for tickets, parking and food.

Whatever the reasons, one thing is for certain: Progressive Field is not to blame. And that brings us back to the smiles. Before The Jake, there were none. Now they’re omnipresent, even if the turnstile figures aren’t what they used to be. The polls, the ticketholders, and the team are all saying the same thing: That life is pleasant at the palace that both saved and rejuvenated Cleveland baseball.

The Ballparks: League Park Rustic, tight and beloved with its cozy sightlines, unpredictable right field wall and a myriad of memorable moments, League Park lived to become the ballyard that wouldn’t go away. Not that anyone complained, as Clevelanders developed a soft spot for the little fellow that has stood the test of time and survived in one form or another all the way to the present day.

The Ballparks: League Park Rustic, tight and beloved with its cozy sightlines, unpredictable right field wall and a myriad of memorable moments, League Park lived to become the ballyard that wouldn’t go away. Not that anyone complained, as Clevelanders developed a soft spot for the little fellow that has stood the test of time and survived in one form or another all the way to the present day.

The Ballparks: Cleveland Municipal Stadium Orderly as it was ordinary, obese as it was austere, Cleveland Municipal Stadium was that rare baseball structure of the early 20th Century, hailed not as a monument to a team owner but to civic pride in a city feeling its oats about the future. Golden moments would ensue, but rust would quickly overtake the stadium and its baseball tenant, rousing cynical locals to declare it “The Mistake by the Lake.”

The Ballparks: Cleveland Municipal Stadium Orderly as it was ordinary, obese as it was austere, Cleveland Municipal Stadium was that rare baseball structure of the early 20th Century, hailed not as a monument to a team owner but to civic pride in a city feeling its oats about the future. Golden moments would ensue, but rust would quickly overtake the stadium and its baseball tenant, rousing cynical locals to declare it “The Mistake by the Lake.”

Cleveland Indians Team History A decade-by-decade history of the Indians, the ballparks they’ve played in, and the four people who are on the franchise’s Mount Rushmore.