The Ballparks

Ebbets Field

Brooklyn, New York

There was nary a dull moment at the fabled ballpark, a funhouse where the rabid fans were almost as famous as the players, so close to the action that fielders could almost feel the vocal gusts of their breaths. From the jolly comic antics of the Robins to the breakout Bums of the 1940s to Jackie Robinson and the Boys of Summer in the 1950s, Ebbets Field was more than just the heart and soul of Brooklyn; it was Brooklyn.

It seems strange to think, when Ebbets Field was built in 1913, that it sat virtually alone amid a vacant expanse of undeveloped city land. The neighborhood would gradually grow around the ballpark and its residents would come to see Ebbets as their social church, the gathering place where the loyal, the cynical and the downright crazed congregated and knelt at the altar of Brooklyn Dodger Blue, praying for one—just one—World Series triumph that always seemed to be just beyond their baseball team’s reach.

No place, before or since, has seen such devoted and outrageous fan support. And no place has seen as many wild moments on the field.

Ebbets Field is the place where Casey Stengel greeted boobirds with one of his own, letting loose a sparrow from underneath his cap. It’s where three Brooklyn baserunners once found themselves on the same base. It’s where two pitchers dueled for 26 innings before everyone gave up and declared it all a tie. It’s where manager Wilbert Robinson created a “Bonehead Club” and made himself the first member when he gave umpires the wrong lineup card. It’s where Hall of Famer Zack Wheat pulled a muscle on his final career home run and struggled to circle the bases. It’s where Frenchy Bordagaray was once tagged out at home, refusing to slide because he didn’t want to ruin the cigars in his back pocket. It’s where yellow baseballs were (briefly) used. It’s where the Dodgers won, then lost, a World Series game when a game-winning strike got away from the catcher. It’s the park where one game was called because of a gnat invasion, and another postponed because of fog.

It’s long since gone, killed by a man who with it killed the fabric of the borough in the name of greed; sentimentality and passion be damned. But the ghost lives on, stronger than ever; if ever a ballpark was to be admitted past the pearly gates, it would be Ebbets Field—and it would be instantly filled by the late great players and fans who together would get crazy all over again.

Fleeing the Stench.

Fifty years before Walter O’Malley’s cold-hearted betrayal of Brooklynites, there was Ned Hanlon, the former skipper of the great Baltimore Orioles teams of the 1890s who now managed Brooklyn and wanted to return to Baltimore—and take the franchise with him. But his bid to buy out the ailing Harry van der Horst fell short when Charles Ebbets secured controlling interest.

Ebbets had worked his way up the Brooklyn team ladder, from a clerk in the 1880s to team owner in 1904. He didn’t want out of Brooklyn, but he did want out of Washington Park, the team’s home since 1898. He had good reason; the air was fouled by nearby factories and the putrid Gowanus Canal, fans were invading an adjacent apartment to watch the game for free, and the rotting wooden grandstand was becoming a growing hazard. Ebbets had visited many of the new steel-and-concrete ballyards popping up across the majors and knew he had to get in on the act.

What followed was a big mystery for Brooklyn baseball fans: They knew Ebbets wanted to build something new, but when and where? Ebbets wasn’t saying. While the guessers imagined a new park near the Washington Park site, Ebbets looked far to the east, past the grown borough, past spacious Prospect Park and upon a square block of land used as a dump and enjoyed mostly by pigs who fed off the garbage. It was lovingly referred to as Pigtown.

Before he could deal with the problem of eliminating the swine and rubbish, Ebbets had to buy the land, a trial in itself. A dozen different people owned parcels within the block, and Ebbets went on the down low—hiding behind an alias company name to purchase the land as cheaply as possible. He succeeded with the first 11 owners; the 12th required a worldwide search before they finally found him across the river in New Jersey. Offered $100 for the last bit of land, he countered with $2,000. The man must have caught on to the ruse—and been a New York Giants fan to boot. Regardless, Ebbets accepted, and the block was fully his.

To cover the $750,000 it would cost to build the new ballpark, Ebbets had to sell half his stake in the team; a pair of brothers, Ed and Steve McKeever, took him up on it. The sale had wonderful short-term benefits—without it, Ebbets would have been stuck at Washington Park—but after Ebbets’ death in 1925, it would result in an ugly front office tug-of-war that would linger for decades. Had Ebbets seen the infighting through a crystal ball, he might have instead tried corporate naming rights to get the dough, but that thinking was generations ahead of his time; as it was, he named the ballpark after himself only after someone suggested it to him at a press function.

The area around Ebbets Field seemed curious. It wasn’t rural, but rather an urban landscape waiting to be urbanized, with a grid of streets dotted with just a handful of buildings. But the subway and trolley lines were far from distant, so delivering fans would be a cakewalk. And everyone knew that housing growth around the ballpark was just a matter of time.

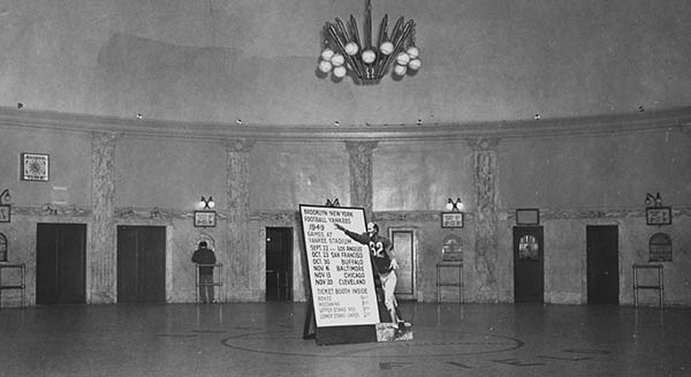

The rotunda inside Ebbets Field’s main entry. The chandelier above included lamp shades doctored up as baseballs.

A Palatial Presence.

Ebbets wanted an opulent look to his ballpark, if anything else to erase the rustic, rotting memories of Washington Park. For this, he brought in architect Clarence Randall Van Buskirk, who sounded like someone with a wicked handlebar mustache and a blimp named after him. (He did have the former but not the latter.)

Van Buskirk created an oasis on the undeveloped outskirts of Flatbush. Ebbets Field featured two tiers of ornate, renaissance-era arches; the upper tier exposed the ramps and concourse except for the 14 that curled above the main entrance and clothed the Dodgers’ main offices. Above both tiers was a more modern (if not industrial) backing of the upper deck, recessed with open-air venting and dotted on the roof with decorative baseball-like orbs displayed like cherries atop a cake.

The main entry beheld more surprises for first-time Ebbets Field visitors. A sizeable, elliptical rotunda 80 feet in diameter and 27 feet high at its central apex was constructed with a mix of metal, iron and stucco and graced in the middle by a chandelier that appeared like a descending spider with its legs bent upward toward the body and featuring illuminated, oversized baseballs. The flooring was a slick display of Italian marble tile and featured, in the middle, the illustration of a baseball with “Ebbets Field” encircling it.

The problem with the rotunda was its inclusion of 14 extravagantly decorated ticket booths that surrounded the floor, equally spaced from one another. Their location caused confusion for ticket holders, ticket buyers and turned-away fans trying to jam their way through a clogged entry into the rotunda—and it nearly caused a riot when the local rival Giants and their rowdy band of fans showed up for the first time and nearly caused a riot as 40,000 people fought for half the available number of seats. Fan flow flaw, concluded Charles Ebbets, who quickly established additional ticket booths along the bases lines outside to reduce the main gate stress.

Van Buskirk and Ebbets further showed their inexperience in ballpark design when, in an even bigger “oops” moment, they designed and built Ebbets Field without a press box. Reporters had to make do with sitting in the first few rows of the upper deck behind home plate, a hazardous predicament given their exposure to fanatical team fans who read their stories and sometimes took issue with them—such as Apple Annie, a vocal, elderly rooter who once bonked a reporter over the head with an umbrella over something he wrote. The media would have to put up with it for 16 whole years before a separate press area was constructed and placed under the upper level in 1929. A second press box was added on the eve of the 1941 World Series, under the upper level roof.

The first-ever game at Ebbets Field—an exhibition against the New York Yankees—revealed more embarrassment. The first fans to arrive had to wait as no one could find a key to the main gate; once they were inside to view the opening festivities, they rolled their eyes once more when it was discovered that they couldn’t raise the Stars and Stripes on the giant center field flagpole. Why? They didn’t have the flag. Someone had to go scrounge around for it.

Spectators were intrigued by the character of the playing field. The confinements of the block Ebbets Field had been built within revealed a somewhat rectangular field that rewarded left-handed pull sluggers who aimed for a tall wall a mere 296 feet down the right-field line; conversely, right-handed sluggers cursed the far more voluminous dimensions in left, which ranged from 419 down the line to over 500 in straight-away center. Defensively, outfielders were in for a real treat catching up to deep drives; instead of warning tracks, Ebbets included a gradual incline similar to what would be seen at Cincinnati’s Crosley Field, and the lower 10 feet of the right-field wall, saturated in advertisements, was tilted outward some 20 degrees. This meant upward caroms from a direct hit—and the opportunity for an outfielder to use the wall and lay against it on a lazy summer afternoon during a pitching change.

The left-field corner of Ebbets Field in 1920. Wooden bleachers had just been added to shave down the spacious real estate in left; a double-deck expansion a decade later would cut more severely into the field and turn the ballpark into a hitter’s paradise. (Library of Congress)

Let the Fun Begin.

The Brooklyn Dodgers had a rough time getting used to Ebbets Field, registering a lousy 29-47 record at home during its inaugural 1913 season while playing .500 on the road. For a ballpark that would be dripping in character from the first pitch to its last 44 years later, it seemed fitting that the Clown Prince of Baseball himself, 22-year-old Casey Stengel—yes, he was actually that young at one time—would hit the first home run at Ebbets, an inside-the-park job. Attendance totaled 347,000 in Ebbets’ first season, a decent number for the time and a franchise record to that point; the gate would ebb and flow through the first few decades of the ballpark’s existence, as would the team’s fortunes—they won National League pennants in 1916 and 1920 before descending into an extended, entertaining period of mediocrity under portly manager Wilbert Robinson, for whom the team was renamed the Robins.

As misery loves company, Robinson’s “Daffiness Boys” of lore attracted a wild breed of Brooklyn supporters who made it loud and clear that the Ebbets Field seats they sat upon would become their personal soapboxes.

There was, of course, Hilda Chester, the most famous of Ebbets Field fans who started showing up in the 1930s and held court in the bleachers, rattling opponents with her cowbells and loud, booming voice to match her large frame. Before Hilda there was the aforementioned Apple Annie, and not far from her seat was Arie the Truck Driver, the real-life inspiration for the Brooklyn Bum who spewed his venom at Robinson’s Robins. The team once tried to give Arie hush money in the form of a season pass on the condition that he’d stop criticizing the players at high volume. But the gag order ate away at Arie, who quickly realized that he couldn’t hold up his end of the bargain and gave the pass back.

Opportunity to expand within Ebbets Field’s petite plot of land proved a challenge. One minor (and thus easy) addition took place in 1920 when a long strip of 2,000 wooden bleacher seats was placed behind the wall from left to center, cutting away some of left field’s spaciousness. But the Robins dreamt big in 1930 when they worked up an idea to more than double the park’s capacity to 50,000 by wrapping the existing double-deck ballpark bowl completely around the field. The plan required closing off Bedford Avenue behind right field, and that didn’t sit well with the Borough’s bosses-that-be who told the team to build on its own land, not theirs; thus, Ebbets’ ambitious scheme was scaled back to 31,000.

The $450,000 makeover radically changed Ebbets’ aura. Gone was the panorama of sky behind the outfield walls, replaced by claustrophobia as the Brooklyn faithful was practically on top of the players from almost every angle of the ballpark. The hitters were certainly happy about one thing; the expansion of seats led to a shrinkage of real estate on the field as Ebbets became utterly live with offense. From pole to pole, home runs were much easier to come by as the once-distant left-field walls were brought in considerably to allow for the double-decked extension. There ultimately would be only one small area of Ebbets’ playing field—a small nook wedged between the end of the first-level bleachers and the right-field wall—that would play at over 400 feet, and just barely.

For umpires and managers, going through the ground rules at refurbished Ebbets Field practically required a master’s degree. The extended stands down the left-field line hugged the field so tight, for the last 12 feet before the pole the top of the retaining wall actually became the foul line; any ball hit off it and ricocheting into the stands would be declared a ground rule double. Over in right, it was no less bizarre after 20 feet of chain-link fencing doubled the height of the right-field wall. In 1940, Cincinnati’s Lonny Frey landed a drive on top of the scoreboard—which rose above the other ads and nearly to the top of the fence—and the ball literally disappeared; it was later discovered that it had found its way through a wooden crack within the back of the scoreboard. Six years later, the Bulova clock atop the scoreboard figured in another funky scene when the Boston Braves’ Bama Rowell launched a drive that crashed through the clock facing and disabled time; it was a moment that wouldn’t be lost on author Bernard Malamud, who wrote up the mythical Roy Hobbs doing the same thing in his novel The Natural.

Perhaps the strangest play in Ebbets Field right-field history occurred in 1950 when the Dodgers’ Pee Wee Reese hit one off the facing of the fence. The ball dropped down atop of one the advertising boards halfway up the wall, bounced a few times and came to a rest in full view of everyone, never to come down to the field. Reese circled the bases, the umpires ruled it a home run and there wasn’t a damn thing the outfielder could do about it.

The tightened Ebbets Field only made the fans come even more alive. While Hilda Chester hollered and rang her cowbells, another Ebbets Field institution was born in the late 1930s when the Dodger Sym-Phony, a rag-tag band of horn players and percussionists who intentionally played off-key, became a prime addition to the brassy Brooklyn crowds. Ballpark personnel at first rebuffed the band—unsure of, well, they weren’t exactly sure. But the musicians found a way to sneak their instruments in and began playing anyway. The fans loved it, and the Dodgers quickly let them play on. Everyone was happy except for visiting players who became the butt of the Sym-Phony’s chorts and crashing symbols the moment they sat down after an out—and a musicians local that once demanded the removal of the band because they weren’t unionized. (The Dodgers scoffed at the request, saying that they weren’t paying the Sym-Phony.)

Hiding within Ebbets Field’s rustic ballpark frame in 1941 was a surprisingly modern concessions area, adorned with mural-sized photos of the Dodgers in action. (Library of Congress)

Sometimes the fans were too close to the action. Too close for umpire George Magerkrath who, after infuriating Dodgers fans with a series of bad calls that led to a Brooklyn loss in 1940, was pinned down and assaulted right at home plate by a livid 21-year-old parolee who jumped out of the stands. The wrath would go the other way on occasion; after a game in 1946, Dodgers manager Leo Durocher—he of the friendly mob connections—asked security to summon a fan who’d been riding him all day to meet him under the stands; stupefyingly, the fan agreed, went downstairs and took a pummeling from Durocher and Ebbets’ top security man Joe Moore, breaking the fan’s jaw. Durocher and Moore were eventually declared not guilty in a court of law but did have to pony up $6,750 in a separate civil suit.

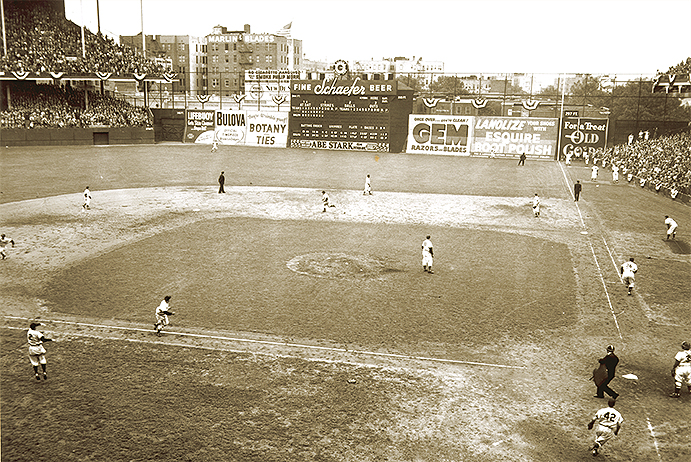

There was personality to be found on the outfield walls as well. One of the early and more famous advertisers at Ebbets Field was Abe Stark, whose clothing store ad always promised suits to players who hit his sign; when the voluminous ad became an easy target and his store a frequent destination for hitters who collected, he had the billboard’s size reduced and move to the base of the scoreboard. Atop the scoreboard, Schaefer Beer got a lot of eyeplay and served as the messenger for the official scorer, who lit up the “H” in “Schaefer” when a hit was given and the “E” when it was an error. It was reported that Schaefer brought in one of their employees to operate the sign after the original deal to give the official scorer a weekly case of beer proved a little too much.

Making Ebbets MacPhail-Safe.

Brooklyn’s baseball ascension from laughingstock to elite power began in 1938 when Larry MacPhail arrived on the scene from Cincinnati. As the general manager of the Reds, MacPhail had resuscitated a franchise that had sat lifeless both on and off the field; his most famous innovation was to bring night baseball to the majors. With the Dodgers, he wasted little time, spending $200,000 to spruce up Ebbets Field with a fresh coat of paint, upgraded bathrooms and hired more ushers who would now where more upscale clothing; he also set up a modern concessions area and bar—“MacPhail’s gymnasium,” as it was sarcastically referred to by reporters aware of his penchant for booze—adorned on the walls with giant photos of Dodgers in action. He spent another $100,000 adding lights to Ebbets—and possibly thought twice about when the Reds’ Johnny Vander Meer threw the second of his two consecutive no-hitters in the ballpark’s first night game.

A year later, MacPhail broke a gentleman’s agreement between the three New York teams and began airing Dodgers games on radio, luring Red Barber away from Cincinnati; the Giants and Yankees didn’t like it, but Barber’s subtle but colorful descriptions of the game reverberated throughout a borough which had grown up and surrounded Ebbets Field, echoing like the wind through open windows and bringing the community closer to the Dodgers—and to itself.

MacPhail doubled the pleasure of Dodgers fans not just by upgrading Ebbets, but the product on the field. Before his arrival, the Robins/Dodgers had become a depression-era wasteland within the majors, second-division nomads playing for a group of owners fighting one another in a neglected and fast-aging ballpark. Within two years, MacPhail, along with the combative Leo Durocher at the helm in the dugout, had turned the Dodgers into contenders, and attendance—which had stagnated around half a million throughout the 1930s—had jumped to seven-digit figures at spruced-up Ebbets.

World War II became a calling card for MacPhail, who left the Dodgers to serve in the Army in 1942. But the team was left in good hands when Branch Rickey, a shrewd observer of talent and the man who pioneered the farm system, took MacPhail’s place after 25 years in St. Louis. With the Cardinals, Rickey single-handedly created a lasting powerhouse; with the Dodgers, he inherited an emerging equivalent and only made it better, the masterstroke being his carefully crafted process of racial integration that made Jackie Robinson a household name. For the next 10 years, Ebbets Field would hit full stride as the ballpark was filled more than ever to watch a Dodgers team better than ever, as Robinson was joined by shortstop Pee Wee Reese, slugging center fielder Duke Snider and fellow African-American ballplayers in lanky ace pitcher Don Newcombe and burly, bruising catcher Roy Campanella to form the storied Boys of Summer teams of the late 1940s and 1950s.

Ebbets Field’s right-field fence during the 1949 World Series. Of special note is the Abe Stark ad at the base of the scoreboard and the “Schaefer” logotype above it—from which the “h” lit up to signal a hit, and the “e” for an error. (The Rucker Archive)

A Tinderbox of Sluggery.

The presence of this potent offense seemed to turn Ebbets Field into not just a bandbox, but a tinderbox of hitting ready to explode. Yet sometimes the occasional pitching duel would break out. Johnny Vandet Meer, he of the 1938 no-hitter, returned in 1946 and threw 15 scoreless innings for the Reds in a game that wound up going 19 innings without a single run before a tie was called. But outside of those two gems, Vander Meer was merely awful at Ebbets, winning two of 14 decisions with a 5.69 earned run average. As a cruel reminder that Ebbets was more unfriendly than not on pitchers, the Reds showed up for a 1952 game—or at least, that was the rumor. The Dodgers were most certainly present and put 15 runs on the board in the first inning.

Over their final decade at Ebbets Field, the Dodgers tore opponents apart as never before or since. In 1950, Gil Hodges ripped four home runs in a game; at the time, he was the fourth guy in the modern era to accomplish that, anywhere. Duke Snider, the Dodgers’ Hall of Fame center fielder, gave great thanks to Ebbets by belting 40 or more homers—the majority of them launched at home—in five straight seasons. And the Dodgers as a team were at their scary best at Ebbets in 1953 when they hit .298 at home and established franchise marks with 60 wins (against 17 losses) and 517 runs—an average of nearly seven per game—in front of the Flatbush faithful.

While opposing pitchers had to be all but dragged into Ebbets to face the Dodgers’ music, visiting hitters couldn’t wait to tee off from home plate. In a 1954 game against the Dodgers, Milwaukee’s Joe Adcock became the fifth player, after Hodges four years earlier, to collect four homers in a game; adding a double to his day of destruction, Adcock’s 18 total bases remained a record for the rest of the century. The Dodgers thanked Adcock the next day by drilling him in the head; Adcock thanked them back a few years later when he reportedly became the only player ever to clear Ebbets’ left-field roof with a deep fly.

Other star players who came to Ebbets hit the ball hard, always. Stan Musial was about as good as the visitors came, hitting .359 with 37 homers and 126 RBIs in 163 career games at Brooklyn. In one 1952 game, the St. Louis slugger laced a ball so hard that it wedged itself into the top of the chain-linked fence above the GEM ad. It took a park attendant, a 30-foot ladder and several minutes of delay to get it down. (The poor guy had to scale the fence another 15 feet when the ladder ran out of steps.)

Willie Mays, in the early stages of his legendary career, was just as good if not better than Musial at Ebbets. In 56 games, he pounded out 28 homers and hit .355; it makes one shudder to think what kind of numbers he could have posted playing in the uniform of the Brooklyn Dodgers.

For all the color, craziness and late excellence that dominated Ebbets Field, the failure to win it all continually bit at the Dodgers and the borough. The team’s first seven NL pennants at Ebbets all segued to World Series losses—the latter five against the crosstown Yankees. After the last of those, in 1953, the Brooklyn Eagle ran out of headlines out of fear of redundancy. “Register to Vote,” shouted the paper after a Game Seven loss to the Yankees; in smaller type below, it said: “P.S. There Was a Game Today.”

The Dodgers only won half of 28 World Series games played at Ebbets; but three of those 14 wins came successively in 1955, when they finally won it all for the first and only time in Brooklyn. A community that had forever lived with the motto of “wait until next year” loudly shed generations of frustration in celebratory triumph.

The Beginning of the End.

The 1955 world title became the peak crescendo at Ebbets Field. As the Bums and their fans celebrated, Dodgers owner Walter O’Malley—who six years earlier had bought 25% of the team and orchestrated the power structure to ultimately gain majority control of the franchise—was deep in the process of finding a profitable way to jettison the team out of aging Ebbets, if not altogether out of Brooklyn.

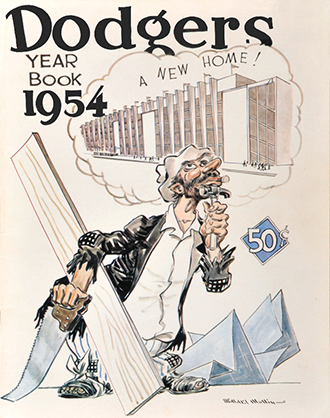

The Dodgers’ 1954 yearbook made no bones of the fact that they were looking to build a new ballpark. At that time, most locals figured such a new place would be somewhere in Brooklyn; a few years later, they weren’t so sure.

For one thing, Ebbets was looking smaller compared to other major league parks with no room to expand. Baseball once had the gall, in 1947, to suggest that a Dodgers-Yankees World Series be played exclusively at Yankee Stadium (with twice the capacity), a notion that was flat out rejected by the Dodgers as a slap in the face to Brooklyn fans. But if the Dodgers could play in front of larger home crowds, they would—as evidenced by the fact that 166,000 fans received refunds for 1949 World Series ticket requests when there simply weren’t enough seats available at Ebbets.

There was another issue. Brooklyn, once a friendly neighborhood of three million, was slowly devolving as richer residents bolted for the suburbs, inner city decay set in and gangs and graffiti gradually became more commonplace. Increasingly, people were afraid to go to Ebbets, day or night.

The 1953 move of the Boston Braves to Milwaukee further fueled O’Malley’s quest for an alternative to Ebbets. He saw in the Braves’ new ballpark a sparkling new facility on the outskirts of the city with voluminous parking, low rent and full concession revenue. What he also saw: The future. Thus, O’Malley aggressively sought out a new, ideal setting for the Dodgers within Brooklyn. He eyed a prime spot of real estate a mile away from Ebbets at Atlantic and Flatbush Avenues, and prodded local government to help him forcibly acquire the land—which included block after block of existing residences—through eminent domain, a tactic normally reserved for public works projects. The idea was flatly rejected.

Murmurs about a possible Dodgers move to the West Coast had started as early as 1954, but Brooklynites at first laughed off the idea; after all, the Dodgers were perennial leaders in home attendance. But the subject grew legs and became more ominous—and when the Dodgers won it all in 1955, O’Malley rained on the parade by publicly expressing doubts on Ebbets’ long-term future and the need for a replacement. Angered by the lack of progress on Ebbets II, O’Malley sent a warning shot across the bow for 1956 when he moved seven Dodgers home games across the river to New Jersey. When that perceived threat fell on deaf ears, he scheduled eight more games there in 1957—and sold Ebbets to a real estate developer for $3 million. O’Malley the landlord became O’Malley, the tenant. The owner’s Rolodex likely included a few more business cards from moving companies.

For Brooklyn Dodgers fans, the writing was clearly on the wall in the form of O’Malley’s own graffiti. A group of Los Angeles businessmen tried to scrawl it on a Brooklyn billboard welcoming the team to California, but the billboard company rejected the ad. Local grass-roots troops made a desperate and futile attempt to change the momentum, but it was akin to a little man standing on a track and holding his hand out against an oncoming locomotive.

On September 24, 1957, the Dodgers played their final game at Ebbets Field, a 2-0 victory over Pittsburgh behind a five-hit shutout from Danny McDevitt. A crowd of only 6,702 showed up; countless other Dodgers fans were probably too pained to make a final pilgrimage. Gladys Gooding, the long-time Ebbets organist known for her frisky sarcasm, played Don’t Ask Me Why I’m Leaving at game’s end. The Dodgers performed no official ceremony before or after the game, because they officially weren’t moving—yet. That changed nine days later when the Los Angeles City Council gave the Dodgers permission to build a new ballpark north of downtown at Chavez Ravine, sealing the Dodgers fate at Ebbets Field and Brooklyn. The New York Daily News’ Dick Young summed up the heartless irony of the situation when he called the Brooklyn Dodgers—who in recent years were more profitable than any other major league team, the transplanted Braves included—the “healthiest corpse in sports history.”

A Tree Dies in Brooklyn.

Ebbets Field didn’t sit completely idle in its brief post-Dodgers life. Numerous soccer matches, mostly international exhibitions, were played there; it was also the home for several college baseball teams, but only after they received permission from O’Malley—who still paid rent on Ebbets. The last organized baseball to take place at Ebbets occurred on August 23, 1959, with a doubleheader featuring Cuban All-Stars and two Negro league teams. It all seemed so fitting: Two dying breeds—the Negro leagues and Ebbets—coming together in the twilight of their times.

Rumors of Ebbets being temporarily rescued from major league inactivity came to the surface when a planned third circuit, the Continental League—a kneejerk reaction to the departures of the Dodgers and Giants from New York—hoped to put a team at Ebbets until a new stadium could be built. But when the National and American Leagues agreed to expand, the Continentals bowed. Meanwhile, Ebbets was also considered as a first home for the New York Titans (later Jets) in their inaugural 1960 season, but instead began play at the similarly derelict Polo Grounds before the completion of Shea Stadium in 1964.

Ebbets Field Apartments, a low-income residential complex, rises upward today at the plot of land where the ballpark once stood. (Flickr—Josh S. Jackson)

Ebbets stood otherwise lonely, except for a dog that was hired to run loose on the field and scare off would-be trespassers. Roy Campanella—who didn’t make the Dodgers’ trek to California because of a tragic car accident that left him paralyzed—left his heart at Ebbets in the form of his Brooklyn uniform, which he insisted be left hanging in his locker stall until the day the place was demolished.

That day, not surprisingly, came sooner than later. On February 23, 1960, the process of rudely disassembling Ebbets Field began with a wrecking ball painted like a baseball; a recreation of Walter O’Malley’s head would have seemed more appropriate to scorned local Dodgers fans. Out of the rubble, another hi-rise, low-income housing development would be erected. Its name: Ebbets Field Apartments. The place that once saw the Dodgers and Giants do battle now had to settle for the Sharks and Jets.

Just so that no one attempted to recreate any many magical baseball moments from Ebbets Field’s glory days, a sign at the new development decreed: “No ballplaying allowed.”

Alive, More Than Ever.

Over a half-century later, Ebbets Field Apartments remains standing and has outlived its baseball namesake, which perished at the age of 46. But some of Ebbets’ assets survived the demolition. The light standards were moved to nearby Downing Stadium on Long Island. The scoreboard-topping Bulova clock—long since repaired after Bama Rowell’s drive blasted through it—was auctioned to a minor league ballpark in North Carolina. A turnstile is on display at a private sports museum in Los Angeles (of all places). And the Ebbets Field seats are here, there and everywhere, mostly in the hands of private citizens who use them in museums and man caves. Occasionally one will pop up for sale online, but be prepared to spend thousands to get it.

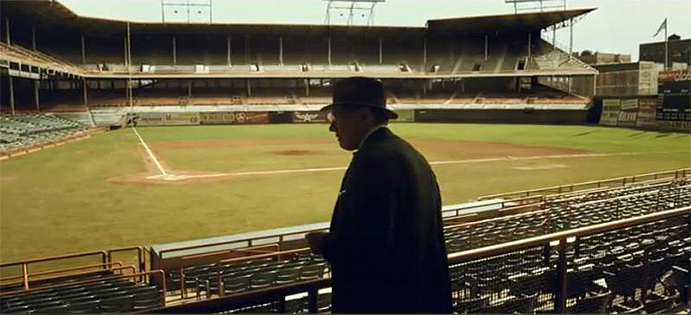

Hollywood magically recreated Ebbets Field via digital effects technology for the film 42. Passing through the foreground is Branch Rickey, as portrayed by Harrison Ford. (Warner Brothers)

The ghost of Ebbets Field would live on in so many ways. The facade to Citi Field, the current home of the New York Mets, is a stylized clone of Ebbets and includes an entry rotunda named after Jackie Robinson. And Brooklyn fans old enough to have frequented the old ballpark must have felt a chill up their spine when, in the big-budget Robinson biopic 42, Ebbets was faithfully and convincingly recreated via digital effects.

Ebbets Field is, essentially, the ultimate lost ballpark. Fenway Park and Wrigley Field survived a date with the chopping block rumored through much of their old age before being re-embraced in the era of retro ballparks at century’s end. Ebbets Field encountered no such luck. When it was torn down, Brooklynites felt as if they could never go home again.

Granted, the borough didn’t die when the Dodgers left. But it was never the same. It would not have Ebbets to rebuild, revive or return to. Only the memories of the times survived.

And what times they were.

The Ballparks: Dodger Stadium The City of Angels felt the need to give the Dodgers the best chunk of available real estate in the Southland, literally moving mountains to wedge a jewel of a ballpark into the sloping, sun-baked Earth amid palm trees and Pacific breezes. Within sight of downtown and the towering San Gabriel Mountains in the distance, it’s a ballpark you can only love but cannot label. It’s not retro. It’s not modern. It’s just…perfect. It’s time for Dodger Stadium.

The Ballparks: Dodger Stadium The City of Angels felt the need to give the Dodgers the best chunk of available real estate in the Southland, literally moving mountains to wedge a jewel of a ballpark into the sloping, sun-baked Earth amid palm trees and Pacific breezes. Within sight of downtown and the towering San Gabriel Mountains in the distance, it’s a ballpark you can only love but cannot label. It’s not retro. It’s not modern. It’s just…perfect. It’s time for Dodger Stadium.

Los Angeles Dodgers Team History A decade-by-decade history of the Dodgers, the ballparks they’ve played in, and the four people who are on the franchise’s Mount Rushmore.