The Ballparks

The 1910s-1920s: Steel and Concrete

Baseball’s modern era comes of age with the help of the sport’s first ballpark boom, as sturdy, cutting-edge palaces show off grace and confidence to mirror the game’s growth.

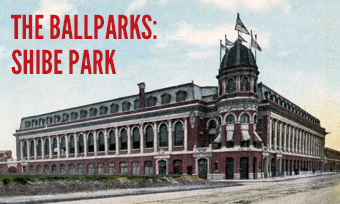

Philadelphia’s Shibe Park set the pace for the steel-and-concrete era and could have easily been confused by locals for an opera house from the outside. That it housed baseball astounded those who were used to envisioning ballparks as rustic wooden relics. (The Rucker Archive)

In 1909, the training wheels came off the American ballpark. It was that year that new two facilities, Philadelphia’s Shibe Park and Pittsburgh’s Forbes Field, opened the gates to the steel-and-concrete era and showed America that big-league baseball had grown up. Beyond the ironworks, the main entrances at Shibe and Forbes exuded class and dignity, an uppity level of friendly respect previously unseen at a ballpark. The maturation of the majors’ budding modern age received a majestic shot in the arm with the arrival of these two new ballparks; the ruffians who ruled the grandstands 10 years earlier now came across as passé fools sitting within more civilized environments.

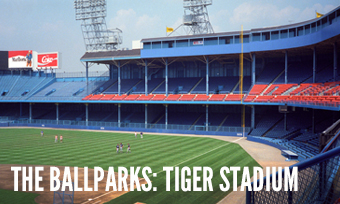

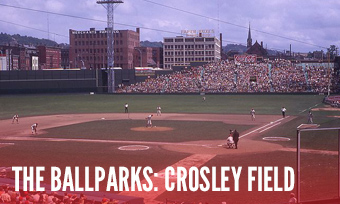

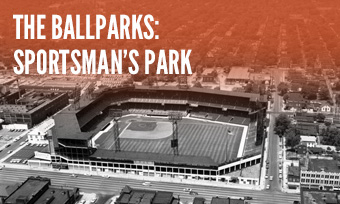

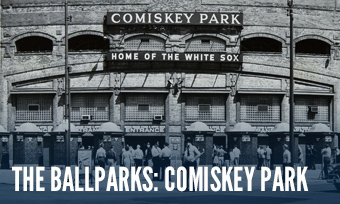

Shibe and Forbes proved there would be no turning back. Overnight, the wooden relics of yesteryear would be shaken (or burned) down and redressed in steel and concrete. Cincinnati’s Palace of the Fans became Redland (later Crosley) Field, Washington’s American League Park became Griffith Stadium, and Detroit’s Bennett Park became Navin Field (later Tiger Stadium); Cleveland’s League Park, St. Louis’ Sportsman’s Park and New York’s Polo Grounds would get a steel-and-concrete makeover; and whole new venues would be constructed in Boston (Fenway Park), Brooklyn (Ebbets Field) and Chicago (Comiskey Park). The building of Boston’s Braves Field in 1915, followed a year later by the Cubs’ move into Weeghman Park—originally built for the short-lived Federal League and later to be known as Wrigley Field—completed a remarkable seven-year transformation within the majors in which primarily wooden ballparks had decreased from 15 to one.

In a time before union prevalence, city council meetings, environmental reviews and OSHA requirements, the new wave of steel-and-concrete ballparks was built quickly and with relatively little expense. The Pirates constructed Forbes Field for a cool million; the Pirates splurged. All other ballparks of the period were built for under $500,000, and some were erected as quickly as three months depending on the urgency—such as the Polo Grounds’ 1911 midseason redo in the wake of the devastating fire that brought down its wooden predecessor.

Picking a location also engendered little resistance. Many baseball owners had financial and political power to choose their ideal spot, and any public opposition was minimal given the amount of open land still available to develop within city limits. The strength of the owners’ political connections also ensured that their ballparks would be built alongside subway or trolley lines.

The urban nature of the new ballparks led to some intriguing panoramas from the average box seat. If it wasn’t commercial buildings looming high beyond the bleachers, it was neighborhood homes tall enough to charge knothole fans to sit on rooftops or upper-story window sills to watch the action from outside the turnstiles, frustrating those trying to sell tickets on the inside; it’s a practice that still occurs today outside of Chicago’s Wrigley Field through a prickly alliance between the Cubs and their neighbors.

Wrigley Field, taken on the day of its very first game for its original tenant: The Chicago Chi-Feds of the short-lived Federal League. Along with Boston’s Fenway Park, Wrigley remains in service over 100 years after its opening.

Fitting into the neighborhood also led to an abundance of asymmetry on the playing field. Most outfield walls abutted to city streets while a few had to detour around homes and businesses whose owners refused to sell, successfully testing the political clout of team owners. Still, the ballparks had plenty of room leftover to satisfy those who craved the Deadball Era and its low-scoring, station-to-station character. With some genuinely cozy exceptions (right field at Philadelphia’s Baker Bowl, down the lines at the Polo Grounds), any chance of mashing a mushy ball over the fence in any of the steel-and-concrete parks would have to come with wings and a prayer. Field distances to center field measured well over 400 feet from home plate; in a few cases they went beyond 500. Even hitting down the lines offered little chance to clear the fence. To wit: Ebbets Field, more known for its glory days of the 1940s and 1950s as a hitter’s paradise, initially did play small down the right field line at 301 feet—but down the left side, it was 419. Few ballparks today measure that far to center.

Outfielders were no less thrilled having to cover such great expanses, and they had other bones to pick as well—like those of their own they had to pick off the ground after slamming into walls made mostly of concrete. Additionally, the turf of the times was rough, faded or simply non-existent, hardly equal to the exceptional quality of those used today; some teams even saved on mowing equipment by employing sheep to graze the grass.

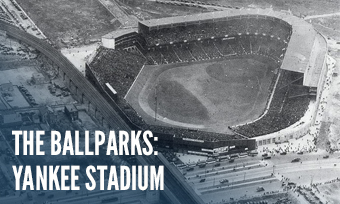

Proving that they could never be outdone by anyone else, the New York Yankees capped the steel-and-concrete era by building, easily, the largest ballpark of them all: 70,000-seat Yankee Stadium. (The Rucker Archive)

The steel-and-concrete era came to an epic crescendo in 1923. The New York Yankees, a burgeoning superpower blessed with the game’s ultimate superstar in Babe Ruth, were kicked out of the Polo Grounds by their jealous landlord and crosstown rival in the Giants. Fueled with visions of greatness, the Yankees thought big for a new ballpark. And so they built big. Yankee Stadium would be the last and grandest of the era’s ballparks, an unprecedented three-tiered behemoth whose seating capacity would top out at over 70,000. Its opening, and its enduring stature, helped ensure Yankee dynasties for generations to come.

The legacy of what’s often cited as the golden age of ballparks can be found in its influence and longevity. Shibe Park, Forbes Field and Crosley Field each lasted roughly 60 years. Comiskey Park, 80 years. Tiger Stadium and Yankee Stadium, nearly 90. And over a century after opening their gates for the first time, Fenway Park and Wrigley Field still remain alive and vibrant as ever, baseball Meccas for those seeking to make the pilgrimage amid the newer ballparks that in large part have paid their own homage to the architectural splendor and urban ambiance of their ancestors.

Forward to the 1930s-1950s: Dormancy Depression and war embolden the general attitude of most major league teams to contentedly sit it out at their existing ballparks, which undergo expansion and are outfitted with lights for the night.

Forward to the 1930s-1950s: Dormancy Depression and war embolden the general attitude of most major league teams to contentedly sit it out at their existing ballparks, which undergo expansion and are outfitted with lights for the night.

Back to the 1860s-1900s: Lumber and Crossed Fingers From open pastoral settings to medieval frameworks, the 19th-Century ballpark endures through a fragile evolution as the use of wood led to multiple hazards, most occasionally that of fire.

Back to the 1860s-1900s: Lumber and Crossed Fingers From open pastoral settings to medieval frameworks, the 19th-Century ballpark endures through a fragile evolution as the use of wood led to multiple hazards, most occasionally that of fire.