THE BALLPARKS

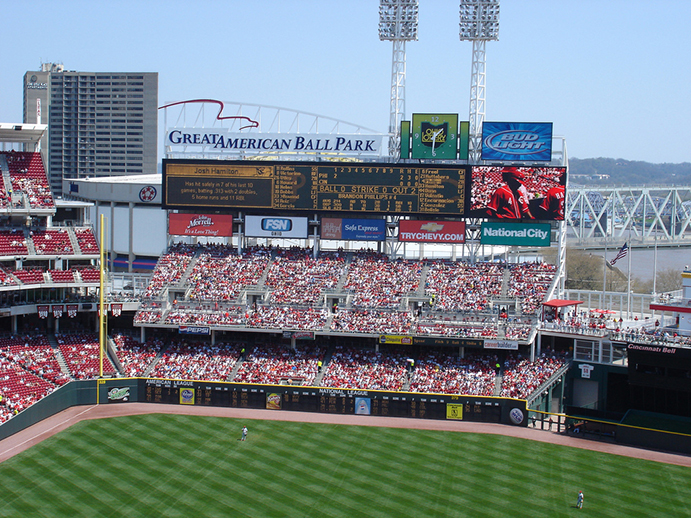

Great American Ball Park

Cincinnati, Ohio

(Flickr—Ray Marecki)

The home of baseball’s First Team is not so much a ballpark but an array of inviting neighborhoods, a diverse riverfront community that embraces old and new alike and opens its patio to the Ohio River with charm to rival a Mark Twain novel. Want a peak? It’s easy to do from the water, and not much tougher from downtown thanks to the intriguing gap that allows fans to see the city and vice versa.

(iStock)

Baseball wasn’t born in Cincinnati; it was merely perfected there, with the Red Stockings—baseball’s first professional team—once winning 130 straight games. A century and a half later, this great game is more alive than ever in the Queen City, and Great American Ball Park is driving that pulse.

Within the ballpark’s boundaries, the heritage comes alive; a myriad of art at Great American’s front gates pays tribute to the Reds of recent years, yesteryear and the years before that, while a glorious Hall of Fame—perhaps baseball’s most impressive outside of Cooperstown—brings to life Reds heroes from John Reilly to Joey Votto. Within its steely white bowl, the amenities are alive, allowing fans to imbibe, ingest and breastfeed—yes, breastfeed—in ideal comfort. And within the lines, the ball certainly seems alive—just ask any pitcher who’s taken the mound and watched home runs sail over the fence with greater regularity than what they’re used to. Great American Ball Park may not be a mile high, but the hitters certainly feel that way when they go deep.

At most ballparks, fans talk about asymmetrical field dimensions; at Great American Ball Park, they talk about the asymmetry of the seating, with a uniquely designed layout featuring at least a dozen main seating options to choose from. It’s not just a simple matter of choosing to sit in the first, second or third deck; it’s more the question of, do you want to sit in the more expansive second deck on the third-base side, the lower “party deck” seats on the third deck along the first-base side, or—if you have the money—the suites above the smaller middle deck on the right, or the row of suites at the back of the field level on the left?

This intentional schizophrenia of seating is made possible by The Gap, which has become Great American’s most talked-about feature, even more than the faux riverboat and smokestacks beyond center field. The Gap is an open fissure between the upper two decks near home plate, and it serves multiple purposes: To allow for the aforementioned, dissimilar seating arrangements; to bring fans situated along the left-field line closer to the action; and to provide breathing space and give a sense, however subtle, of a connection to downtown as the rest of the ballpark opens up to the more expansive yet tranquil scenery of the Ohio River and the Northern Kentucky hills beyond.

Back to the Riverfront.

There was no such vista to be found within the Reds’ former home of Riverfront Stadium, an enclosed concrete bowl which was built as part of the multi-purpose civic stadium craze of the 1960s and 1970s. Like most stadia of that era, Riverfront had survived into the 1990s but become increasingly frowned upon as newer, more intimate facilities began to sprout up throughout the national baseball landscape; even worse, Cincinnati was pouring virtually no upkeep money into Riverfront, making it look even older than its cookie-cutter brethren. The NFL’s Bengals, Riverfront’s Reds roommates who sued the city in the 1980s over the lack of touch-up funding, publicly threatened a move out of town in 1992 if they didn’t get a new stadium exclusively tailored to their own needs. A year later, the Reds began grumbling as well—especially after seeing what brand-new Oriole Park at Camden Yards had done for Baltimore and the Orioles with its retro-fueled, baseball-specific quirks.

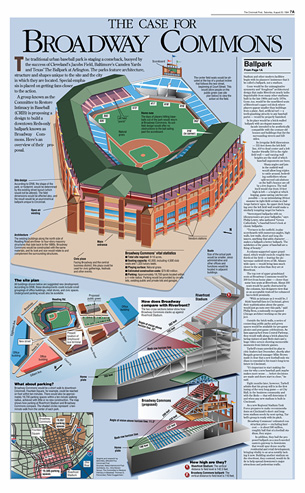

This page from the Cincinnati Enquirer in 1998 lays out the pros and cons of a Reds ballpark located not at the riverfront but nearly a mile north, near Over-the-Rhine. Voters eventually said no to the idea, by a wide margin. (Cincinnati Enquirer)

Amazingly enough, getting citizens to okay public funding for a new Reds ballpark was the easy part. A more contentious decision lay ahead: Where to build it. The Reds and county officials idealized a spot right next to Riverfront Stadium, but Cincinnati’s mayor, the City Council and business leaders began pushing for a triangular space of open land near the historic Over-the-Rhine neighborhood, a half-mile north of the riverfront—even teasing the Reds with $20 million in bonus money to help get it built. Leading the fight for the alternative site, called Broadway Commons, was City Councilman Jim Tarbell, who had a bit of incentive; he was owner of Arnold’s Bar and Grill, Cincinnati’s oldest restaurant, which just happened to be walking distance from the Broadway Commons site. Something else was even closer: The county jail, which stood right across the street from the proposed ballpark’s main gate. As Broadway Commons proponents forced a ballot measure and ran commercials telling voters to “Think back, look ahead,” riverfront advocates referenced the jail and retorted with “Look behind your back.” Most everyone outside of government wanted the ballpark on the riverfront anyway; not even a 1997 flooding of the Ohio River into Riverfront Stadium—by now renamed Cinergy Field—was enough to change voters’ minds; 65% of them said no to Broadway Commons in the Fall of 1998. The city eventually allowed a casino to be built there instead.

With the vote behind them, the Reds were happy to completely focus on the riverfront—but unhappy to find that the Bengals were taking up most of the available space, with roughly 12 square blocks devoted to the stadium, practice fields and parking. It was part of a pattern from which the Reds clearly felt that the NFL team was receiving preferential treatment; besides the abundance of land, the Bengals were first in line to get their venue built, and for a lot of money—with cost overruns, Paul Brown Stadium eventually ate up 90% of the budget allotted budget for both teams, leaving officials scrambling for additional financial sources to pay for a Reds’ ballpark. So little money was left that serious talk ensued on whether it would be cheaper to do a moderate makeover of Cinergy Field for the Reds.

Out of frustration, controversial Reds owner Marge Schott—she of the used car scams, re-gifted flowers, racial slurs and the infamous comment that Adolf Hitler “was good in the beginning”—publicly threatened a move to Kentucky or Indianapolis if the Reds, which had laid their roots nearly a full century before the Bengals, didn’t start getting equal consideration. Local politicians yawned at Schott’s threat, understanding that no MLB team had relocated in nearly 30 years—while five NFL teams had moved within the previous decade, helping to fuel Cincinnati’s fear and, thus, its bending over backwards for the Bengals.

Originally hoping to get land to the immediate west of Cinergy Field, the Reds were now forced to wedge a new ballpark into a relatively small plot on the other side, between Cinergy and the Riverfront Coliseum (which currently goes by the name of U.S. Bank Arena). It was impossible to build the 42,000-seat venue without trespassing upon the footprint of at least one of the existing facilities; Cinergy ended up drawing the short straw, and 15,000 of its outfield seats were dismantled to allow for an overlap of ballpark construction. Throughout the Reds’ last season at Cinergy in 2002, fans got to see the new venue, branded as Great American Ball Park after the local insurance giant paid $75 million for naming rights, slowly rise; only 36 inches separated the Reds’ old home with the new at its closest point, which led the team, their fans and the new ballpark’s contractors to tightly cross their fingers at the end of the year when Cinergy was imploded. Sighs of relief were audible everywhere as Great American Ball Park survived the event dusty but unharmed.

The debris on Cinergy cleared, Great American Ball Park could now move forward toward total reality as envisioned by its lead architect, Kansas City-based HOK Sport.

This digital artist conception shows a proposed Great American Ball Park (left) and how it fits in with the rest of the riverfront—most of which has already been taken over by the new digs of football’s Bengals, Paul Brown Stadium (right). (Courtesy of Rand Shear)

A Complex Assignment.

Hired in 1999, HOK initially and briefly answered to Marge Schott before baseball, tired of her endless controversies, forced her out. “She had instincts,” said Rand Shear, HOK’s lead designer on Great American. “When we showed her our drawings, she always shook her head no—then she saw the very last one, and she nodded, ‘yes’.”

That last drawing initiated an evolution on the project between HOK and Schott’s successor in design talks, Reds Chief Operating Officer John Allen, who had definite ideas about what he wanted in the new ballpark and worked smoothly with the architects, no longer worried about being goosed at the conference table by Schott’s St. Bernard, Schottzie.

Although HOK had brought the past successfully to the present with Oriole Park at Camden Yards, it had the idea of merging old and new as it did with Cleveland’s Jacobs (now Progressive) Field. The amount of research and knowhow added to a complex assignment with the goal of a pleasing balance. “We’ve tried to incorporate the important elements of the city in the stadium—bridges, city and river, stone and steel,” said HOK project lead Joe Spear to the Cincinnati Enquirer. “This is probably the most complicated project we’ve worked on.”

“You do a lot of research on the architecture and culture of the city,” said Shear. “You take in the culture, the food, the ice cream, the chili…you have to engrain yourself into the culture, you have to stay there for a time to get the feel of it.”

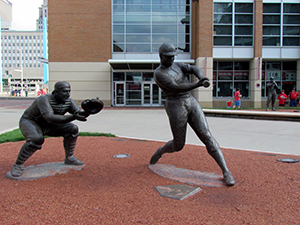

The design team did its homework on the history of the Reds as well. It focused mostly on Crosley Field—the Reds’ home for the better part of the 20th Century—and it shows at Great American Ball Park’s front entry, a park-like plaza triangularly enclosed by the ballpark bowl, the Reds’ Hall of Fame and the team’s main office building. It’s essentially an all-around tribute to the Crosley era, with bronze sculptures of four Reds legends of the time (Ted Kluszewski, Ernie Lombardi, Joe Nuxhall and Frank Robinson), and several strips of grass berms cutting into the concrete, sloped at the same angle as Crosley’s famed terraced warning track.

Inside the ballpark bowl, more Crosley homages await. The toothpick-shaped light standards sit atop nostalgic, tripod-like towers. A massive scoreboard above the upper deck of the left-field bleachers includes a replica of Crosley’s Longines clock—except that it wasn’t long before it became the Mountain Dew clock, or the Ohio Lottery clock or the Sofa Express clock. (Revenue trumps tradition.) There was one famous aspect of Crosley that failed to get leveraged to Great American Ball Park: The grassy warning track incline, for which there was actual discussion over until the Reds concluded that it would be too hazardous for outfielders.

Atop Great American Ball Park’s left-field bleachers is the main scoreboard, further topped by a clock originally was sponsored by Longines, whose name was long used on a similar clock at old Crosley Field. Sponsors with more money to offer have apparently come along. (Flickr—Robert Meeks)

Great American’s true kitsch lies behind center field. High above the batter’s eye is a faux riverboat missing many of its critical components—it could use a paddle wheel and smokestacks—and serves as a private deck for groups of 20 or more. Nearby, next to the right-field bleachers, are—well, what do you know—a pair of smokestacks, which spout flames whenever an opponent strikes out, or fireworks when a Reds player goes yard. The stacks also serve as one of many tributes throughout Great American Ball Park to fallen Reds hero Pete Rose, who’s still highly beloved in Cincinnati; atop each stack are seven bats bending outward—7 x 2 = 14, Rose’s uniform number.

Get into the Gap.

But talk to most people who show up at Great American Ball Park and the focus will eventually zero in on The Gap, the 35-foot separation between the upper two decks near home plate.

“The gap was…envisioned to follow the street grid of Cincinnati, connecting to Sycamore Street, and to take advantage of views of the Ohio River and ensure those beautiful views could actually be seen by fans in the stadium,” recalled Joe Spear on the Populous web site.

“That line of connection is a way we have people not only see into the ballpark but see through to the boats going by in the river,” said Rand Shear. “So it’s pretty powerful.”

Some people didn’t get The Gap at first. In the design stages, Shear found himself as the lone HOK representative at a public meeting in which sketches of the ballpark—complete with The Gap—were being shown. Councilmember Jim Tarbell, he of the failed Broadway Commons lobbying effort, was puzzled by the open crack in the stands. So he asked, as if to challenge the idea: “What do you see when you’re in the bowl and you look out through that gap?” Shear got up, introduced himself and simply replied: “You see the city.” Tarbell leaned toward the microphone and said, with newfound enthusiasm, “That’s interesting.”

As seen here from the right-field corner, the “Gap” behind home plate exposes a sneak of downtown Cincinnati. Two things to note: The difference in seating arrangements on both sides of The Gap, and the tall building towering behind; it’s the headquarters for Great American Insurance, for which the ballpark is named after (albeit for a price). (Flickr—Daniel Betts)

It’s a Lot of ‘Sort of.’

The first public glimpse of Great American Ball Park’s designs was met with mixed reviews. While some praised the mix of modernity and antiquity, others hoping for a full-blown retro facility along the lines of Oriole Park at Camden Yards were left less satisfied. Local architects were particularly harsh, perhaps because they didn’t get the job. “Overall, it’s bland,” said David Scheer, principal of Scheer and Scheer Inc., to the Enquirer. “It’s sort of urban, it’s sort of retro, it’s sort of contemporary. It’s a lot of ‘sort of’…It’s light years ahead of Paul Brown (Stadium), but it doesn’t know what it is trying to do.”

But HOK knew exactly what it was doing. Great American Ball Park really doesn’t fuse new and old; it’s more or less the new surrounded by the old. The ballpark bowl, with its predominant use of steel (painted white as an ode to the riverboats passing by on the Ohio), is surrounded by buildings largely constructed with brick facades, with a dressing of sandstone at its base.

There’s also a class structure at work within the ballpark. Chances are, if you’re sitting on the first base side, you’ve paid more—but you also get closer proximity, and likely better access, to the ballpark’s high-end perks. This area is, after all, where most of the suites and club-level seating are situated—part of the neighborhood aspect, as Joe Spear called it. There certainly is a more formal feel to the exterior and the concourse beyond, with glass panes slanted outward amid the steel and touches of sandstone. Over on the third-base side of the Gap, more seats for the common man reign, with suites restricted to a portion of the field level behind the box seats; behind those is an expansion of the concourse with a spectacular high ceiling—“nothing like any other ballpark,” Shear claims—held up by industrial-styled arches and featuring an arcade of food options, including some of Cincinnati’s more popular local institutions from LaRosa’s Pizza to Skyline Chili, famed for a chili dog topped with gobs of cheddar. Further emphasizing the middle-class trend along the left-field line, the glass and stone give way to bricks, which finally come into play as part of the structure on the northeast (left-field corner) exterior.

A revealing look at the main gate and the three concourse levels behind. The modern look initially put off some in Cincinnati who were wedded to the concept of a ballpark dressed in a more antiquated, retro-oriented outfit. (Flickr—Geoff Livingston)

In total, nearly half of Great American’s 42,000 seats are on the field level, as opposed to just a fifth of Riverfront Stadium’s 50,000. But there are only 10,000 of any one “seat type” at Great American, something decreed by the Reds’ John Allen during the initial discussions with HOK. “We just want to have something that can’t be copied anywhere else,” Allen once said of the ballpark. It’s quite possible that he has achieved that goal.

Reds fans eagerly awaited the ballpark’s opening. Great American’s 51 suites sold out in 27 minutes, shattering the old mark previously held by Pittsburgh’s PNC Park. An open house held shortly before the first game attracted over 200,000 people, allowing them their first glimpse of the field, the seats, Crosley Terrace and a few other curios. Among them: A 50-foot-tall art deco limestone relief mural entitled the “Spirit of Baseball” to the left of the main gate; side-by-side mosaics in the lower concourse depicting two different but equally unstoppable Reds teams—those of the 1860s on the left and, on the right, those of the 1970s; and outside the gates along Joe Nuxhall Way toward the Ohio, a rose garden establishing the spot where Pete Rose’s 4,192nd hit landed on the artificial Riverfront Stadium turf in 1985. (The Johnny Bench bench would have made a nice accompaniment to the garden, but it failed to make the final cut.)

“You’re Really Good.”

Opening Day traditions abridged themselves to Great American Ball Park’s debut. The traditional Findlay Market Parade snaked through downtown toward the new yard. Near the gates, the Pete Wagner Band, a Reds institution of sorts since 1954, charmed the incoming fans. Former President George H. Bush threw out the ceremonial first pitch; he might have had better stuff on the day than Reds starter Jimmy Haynes, who was clocked for six second-inning runs as the visiting Pittsburgh Pirates did all they could to spoil the Great American party with a 10-1 rout on a chilly end-of-March day. But 42,343 were still smiling at game’s end, absorbing the new grounds for the first time with great approval. Among the impressed was a woman sitting in the upper deck near The Gap, sharing her praise of the ballpark with her friends. She was then poked in the side by the man sitting next to her. “Did you know I designed this ballpark,” Rand Shear quizzed. The woman turned to him, skeptical. “I’m a pretty gullible person,” she replied, “but I know for a fact that you didn’t.” To prove his point, Shear spent the next three minutes giving enough facts about Great American Ball Park to fill up a Wikipedia page. When he was done, the woman, impressed but still unconvinced, smiled. “You’re really good,” she remarked.

The Reds, on the other hand, weren’t really good at all during their inaugural season at Great American, finishing 69-93—35-46 at home, their worst showing to date. Injuries and bad pitching had much to do with it; the team’s three biggest stars—Ken Griffey Jr., 39-year-old Barry Larkin and all-or-nothing slugger Adam Dunn—were all chronically sidelined before they were all shut down in late August, while 17 different pitchers started at least one game and posted a combined 5.77 ERA. The patchwork effort likely had an effect on attendance; the final gate at Great American’s first season was 2,355,259, which didn’t break any records—the Reds drew more at Cinergy Field just three seasons earlier—and once the new ballpark smell wore off, they drew even less in the years to follow before rebounding in the 2010s when the team hit on a competitive streak. But there was no debate that the building of Great American had been done in vain; had the Reds been stuck at Cinergy, they would have suffered on the revenue front and the team would have been far more challenged trying to rise in a division where everyone else had new digs (except the Chicago Cubs, playing at historic, soon-to-be-made over Wrigley Field).

We’re Only 500 Feet Above Sea Level, Right?

Fans looking for offensive baseball at Great American have come to the right place. The ballpark’s reputation as a home run haven is justified, always listing near the top of major league venues every year in big flies; Great American witnessed at least 210 homers in each of its first six years, and it topped all ballparks in 2005 with 246 total homers, the same year an average of 11 runs per game were scored. (It’s always good to bet the over at Cincinnati.)

So what causes the hit parade? A little bit of everything. The foul grounds are small, giving hitters more second chances than they might elsewhere; the field dimensions are relatively smug, with distances in the 320s down each line, 379 to left-center and an easily reachable 370 to right-center; and then there’s The Gap, whose opening allows prevailing breezes from downtown to create a wind tunnel effect toward the outfield. This all could have been worse for pitchers; in the design stages, the Reds originally conceived the right-field foul pole being a mere 316 feet from home. The National League said fine, but only on the condition that it be backed by a tall outfield wall. Worried that this would obscure more fans’ view of the Ohio, the Reds decided against it.

The presence of the Ohio might beget visions of fly balls splashing into the drink a la other waterfront parks in San Francisco and Pittsburgh, but a little education is in order; the closest distance to the river from home plate is 580 feet. Adam Dunn certainly scored some points, however, in Great American’s second year when he hit the ballpark’s longest homer to date at 535 feet. The ball cleared the steamboat in center, bounced across Mehring Way outside and down a concrete embankment beyond, finally resting onto a piece of driftwood floating in the Ohio. Some suggested that it was the first major league home run hit into another state.

A recreation of a steamboat and smokestacks—why the latter is separate from the former, we don’t know—brings riverfront flavor to Great American Ball Park. (Flickr—Christopher Paulin)

Of Beer and Mother’s Milk.

Over a decade old now, Great American Ball Park has seen its share of tweaks and additions. The large scoreboard was upgraded with a high-def screen in 2009. The Reds Hall of Fame continues to evolve and feature new exhibits. The Machine Room Grille, a steel-and-brick ode to the Big Red Machine teams of the 1970s that serves upscale grub behind the left-field corner, has seen its business hours waver as foot traffic has been hard to come by when the Reds aren’t in town. In 2014, the Reds debuted the Reds Brewery District, a cool, 85-foot strip of bardom on the third-base side of the lower concourse that features a mix of some 20 local and national beers. And a year after that, the Reds paid heed to an entirely different kind of tap when they opened a nursing suite, allowing mothers to breastfeed their newborns in a country-style setting predominantly decked out in red and white. The nursery is the first of its kind in a major sports facility and is the brainchild of current Reds COO Phil Castellini, a father of five. Because revenue is everything to major league teams, the nursery has a sponsor—and so, naturally, it’s Pampers.

There’s been maturity outside the gates as well with mixed-use development sprouting west of Great American Ball Park. Across Joe Nuxhall Way and facing the Ohio is the Moerlein Lager House, a two-story brew pub that brags of concocting the first beer “to certifiably pass the strict Reinheitsgebot Bavarian Purity Law of 1516,” which is certainly saying something even if means nothing. One block up, on Freedom Way, is where the heart of the pre- and postgame entertainment thrives. Called The Banks, it’s a solid block of chic condos looking down on restaurant upon restaurant, everything from Johnny Rockets to Jimmy Johns to Ruth’s Chris Steakhouse. There’s also a number of other brew pubs and nightclubs, but just to make sure that everyone’s behaving in a town that gave the world shameless talk show host Jerry Springer, smut lord Larry Flynt and YouTube legend Markiplier, the Cincinnati Police Department has an outpost stationed on the street.

The wonderful thing about Great American Ball Park is though it’s named after an insurance giant, it could have been some marketeer’s ingenious invention. Many fans continue to think, well, Cincinnati, conservative, card-carrying Midwest berg…yeah, Great American does make sense. It’s old, it’s new, it’s something for everybody—except maybe the pitchers.

At the top of the Reds’ brick office headquarters that slices away from the bowl on the third-base side, big italic letters quote the famous adage of former Reds pitcher and announcer Joe Nuxhall: “Rounding Third and Heading for Home.” For Cincinnatians, the majority of whom said yes to building Great American Ball Park, they already feel that they’re there.

The Ballparks: Crosley Field Neither floods nor darkness nor baseball’s most unique warning track could keep the loyal bugs of the Queen City from worshipping their kings in a cherished urban castle where every National League campaign was kicked off. While Crosley Field may have lacked the exterior glam, its interior radiated lush green grass, intriguing wall quirks and romantic views of the environs beyond.

The Ballparks: Crosley Field Neither floods nor darkness nor baseball’s most unique warning track could keep the loyal bugs of the Queen City from worshipping their kings in a cherished urban castle where every National League campaign was kicked off. While Crosley Field may have lacked the exterior glam, its interior radiated lush green grass, intriguing wall quirks and romantic views of the environs beyond.

Cincinnati Reds Team History A decade-by-decade history of the Reds, the ballparks they’ve played in, and the four people who are on the franchise’s Mount Rushmore.