THE BALLPARKS

Rate Field

Chicago, Illinois

(iStock)

Approved at the stroke of midnight—give or take a minute—Rate Field was built to be the king of ballparks but became passé within a year, a soulless venue everyone loved to hate with its vertigo-inducing upper deck and refusal to integrate with the neighborhood. Better late than never, the Chicago White Sox took a decade to catch up to the past and have righted some of the wrongs.

When sports-minded tourists visit Chicago, they tend to beeline it to Wrigley Field. Not so much to watch a baseball game, but to be part of an experience, part of a neighborhood that embraces the ballpark and vice versa with its pubs and restaurants right across the street and residences that welcome you to watch the game from their rooftops.

On the flip side of the agenda and the south side of town, those same visitors likely think little of including Rate Field on the itinerary—unless they’re diehard White Sox fans. It is, essentially, the anti-Wrigley. The only restaurant/pub within shouting distance is ChiSox Bar & Grill, co-owned by the White Sox themselves and part of a larger structure that includes spectator ramps and a skywalk to get fans across 35th Street to the ballpark. The only adjacent residence is an old folks’ hi-rise behind center field, but no one’s putting bleachers upon the rooftop lest knothole fans want a nice view of the backside of the big exploding scoreboard and its giant, surrounding ad panels.

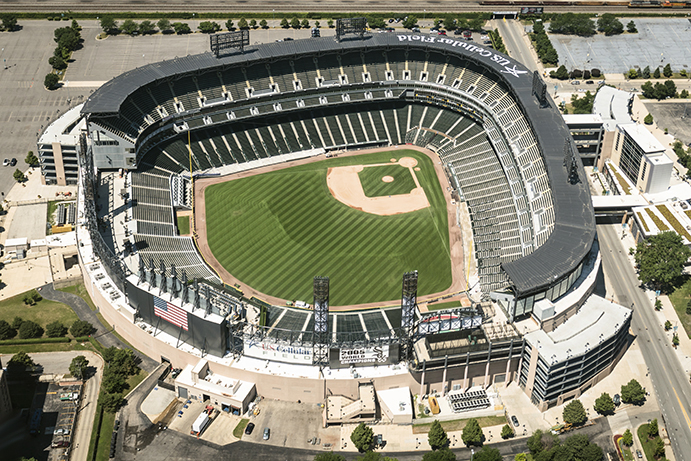

The neighborhood? It’s stiff-armed by the ballpark, cordoned off to the west by railroad tracks, to the east by not one but two Interstate freeways (seriously—the 90 and 94 run side-by-side in the same corridor) and to the north and south by ground-level parking lots that extend nearly a mile. It’s almost as if Rate Field doesn’t dare want you to approach unless you’re coming to watch baseball upon its grounds. The closer you live to it, the more palpable that sense becomes.

So, Rate Field must be a pretty special place to warrant its exclusivity amid a big chunk of Chicago real estate, yes? Not exactly. But it’s trying. When it opened in 1991, the ballpark originally entitled New Comiskey Park was hardly a jaw-dropper from an aesthetic perspective, appearing dignified with modest neo-classicism and touches of the Old Comiskey across the street—most notably with its arched openings. But so much of it was (and remains) obscured by a series of switchback pedestrian ramps that might be confused for petite parking garages. Then there’s the inside, where the White Sox’ aspirations of sticking as many seats as possible between the poles led to a lower bowl topped by a whopping three tiers of luxury boxes/club-level seating and, most notoriously, a tall, steep upper deck that felt like an exhausting stairway to heaven for those climbing without mountaineering equipment to reach its highest rows.

Rate Field from head to toe, complete with a vertically voluminous midsection and a steep upper deck; this image was taken after eight rows were removed from the top. (Flickr—Ken Lund)

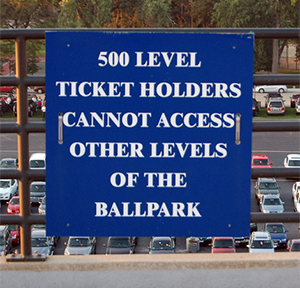

While the White Sox have shaved off the top and given it more roofing to provide a better sense of intimacy—the most visible fix of a patient, seven-year renovation effort—they still haven’t rescinded a policy unheard of anywhere else in the majors: Upper-deck ticket holders aren’t allowed anywhere else within the ballpark. For these fans, “The Cell”—a nickname derived from the yard’s second official title, U.S. Cellular Field—takes on a whole different meaning.

Worse, Rate Field just missed out on the retro ballpark boat. While the White Sox and owner Jerry Reinsdorf focused on emulating contemporary Kaufmann Stadium in Kansas City, built nearly two decades earlier as the last pure ballpark to date, they were unaware—and more likely, unmoved—by what HOK Sport, New Comiskey’s architect, was also up to in Baltimore. When Oriole Park at Camden Yards opened a year later to explosive success and provided an unmistakable influence for every new ballpark to follow, New Comiskey instantly became outdated in the minds of many. Washington-based political columnist George Will, a huge Orioles fan, rubbed it in from Camden Yards when he publicly called New Comiskey the “last stupid ballpark.”

The St. Pete Sox?

When Reinsdorf bought the White Sox in 1981, he knew he was taking charge of the number two team in town. The Cubs, despite all their losing, had the glory, the TV ratings and that place called Wrigley. The White Sox, who weren’t exactly burning up the standings either, had an equally ancient and historic ballyard in Comiskey Park—but it badly lacked Wrigley’s romanticism. No ivy. No bleacher bums. And no Harry Caray, the famed broadcaster who split the White Sox after Reinsdorf’s first year to provide play-by-play for…the Cubs. Before Reinsdorf, master promoter Bill Veeck had tried to make Comiskey come alive in two separate stints as owner, and although he had limited success, it didn’t erase the reputation of Comiskey as an aging relic in a rough part of town.

Reinsdorf knew he had to start thinking of a replacement. He also knew that such a quest wasn’t going to be easy, given that no major sports facility had been built in Chicago since the Roaring Twenties. If he was looking for an ally that would help the White Sox cut through the potential thicket of political and bureaucratic obstacles, he found one in a former law school pal who just happened to be the Governor of Illinois: James “Big Jim” Thompson.

This bronze sculpture of White Sox founder Charles Comiskey, located behind center field, is one of 10 statues to be found within Rate Field. (Flickr—Rob Forgue)

As Thompson struggled just to get a stadium authority set up, Reinsdorf wasted no time and looked west of Chicago to suburban Addison, where he bought a parcel of land in hopes of building a new ballpark. The idea infuriated Chicago mayor Harold Washington, who publicly barked that if the Addison deal got approved by local residents, the White Sox could no longer go by “Chicago.” Reinsdorf laughed, but later frowned when the tally came in from Addison voters: The measure lost by a mere 50 votes, even after pro-ballpark forces had outspent the opposition by 100-1.

Reinsdorf had a fallback to Addison with a replacement venue next to old Comiskey. But what would be the fallback if that failed? One was found 1,000 miles away in St. Petersburg, Florida, where a 40,000-seat domed ballpark had been built on spec to lure a major league franchise. Representatives there were eager to get somebody, anybody to occupy it, and offered the White Sox a sweetheart deal should the New Comiskey project fail to materialize. Armed with leverage, Reinsdorf made it publicly clear: No new Chicago ballpark, no more White Sox. Anyone who thought he was bluffing had to be reminded that he grew up a loyal Dodgers fan in Brooklyn before Walter O’Malley stripped the team to California. Reinsdorf’s hardened heart, law degree and ownership power gave chills to South Side baseball fans who feared defeat of a New Comiskey.

Things got frisky as a vote to approve New Comiskey neared. Chicago Tribune columnist Mike Royko engaged Florida residents in a war of words, telling Chicagoans not to drink orange juice while saying that everyone in St. Petersburg “looks like George Burns.” Reporters, bar owners and patrons in the St. Pete-Tampa area were warned not to return the love, out of fear that it might stoke last-minute support of the ballpark bill in Chicago.

The Day the Clock Stood Still.

On June 30, 1988, the Illinois State Legislature took up the matter of a New Comiskey on the last day of its session. If it wasn’t passed by midnight, the bill would die, Reinsdorf’s patience would have passed its fail-safe point and the White Sox would be Florida’s. Baring all that in mind, Governor Thompson went to work. First, he had to grease the State Senate, needing 30 of 56 votes to get the ballpark okayed; he got 30, exactly. But that was just half the victory; Thompson now had to move the bill to the House, where 60 of 115 ayes were needed with precious time to spare. Working more aisles and twisting more arms, Thompson still found himself six votes shy at five minutes to midnight. Running on political fumes, he furiously lobbied anew but sensed defeat.

At 11:59 Chicago time, Floridians watching all of this on TV began a countdown worthy of Times Square in New York, ready to explode in glee over their new major league team. And then, in the chambers of the Illinois House, the clock went dead. Time officially stood still; Thompson had apparently bought more of it. It was worth the investment. The Governor got his 60th vote, the White Sox got their ballpark and it was officially announced that the bill had been “hereby declared passed at 11:59 p.m.” even as everyone’s watches read 12:03 a.m. Hopeful baseball fans back in St. Petersburg were left stunned in utter disbelief, learning first-hand the mechanizations of Illinois politics as thousands of dead voters in Chicago will tell you.

The approved bill called for a $150 million ballpark, with the public receiving $2.50 per ticket over 1.2 million sold and 35% annually of all broadcast and ad revenue above $10 million; in exchange, the White Sox would get, per year, $5 million in upkeep/insurance costs and $2 million more in cash to do what it pleased. There was also a provision that stipulated, in the Sox’ second decade (2001-10) at the new ballpark, that if attendance fell below 1.5 million, the City of Chicago would have to buy up to 300,000 tickets to make up the difference. (That scenario never played out.)

Piercing the Armour.

With political victory behind them, the White Sox focused on the aesthetics of the ballpark and its surroundings. They were probably well aware that someone else already had a pretty sharp idea in mind.

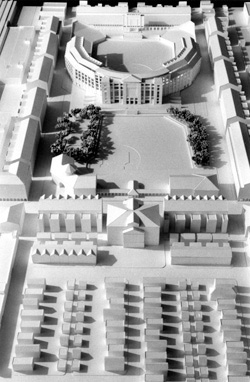

Philip Bess, a respected architecture professor at Notre Dame, had ganged up with the Society for American Baseball Research (SABR) a few years earlier to devise a concept for what a new Comiskey Park should look like. It was a bold vision in a time when enclosed multi-purpose stadia still ruled: An inclusive, inviting ballpark that would open up and fit within the contours of an existing neighborhood, an urban beacon surrounded by housing, retail and restaurants. It would also include a recreational park featuring the ballfield left over from old Comiskey. Armour Field, as it would be called, was just the kind of venue that echoed Wrigley Field and Boston’s Fenway Park, ballparks that emerged organically out of a cityscape and became part of the neighborhood. Ballparks, Bess argued, that hadn’t been built for generations because baseball had become too focused on revenue to engage local residents as part of the plan.

A model of Armour Field, architect Philip Bess’ “alternative” concept for New Comiskey Park that concentrated on integrating the ballpark with the surrounding neighborhood, much like Wrigley Field. The White Sox were disinterested. (Image courtesy of Philip Bess)

“We would cease looking at ballparks in isolation and instead look at them as a component of mixed-use traditional neighborhoods,” Bess later wrote. “We would do this because there is a historic reciprocity between good city neighborhoods and good baseball parks, and therefore this reciprocity should be normative.”

Jerry Reinsdorf and the White Sox would have none of Bess’ retro idealism. Armour Field was to have a gorgeous view of downtown Chicago, but with New Comiskey the Sox strangely decided to look the other way, towards the southeast—where the distant landscape was dotted with hi-rise projects. Apparently, the team was more concerned with cheap home runs and decided to orient the ballpark so that typical winds from the southwest wouldn’t push fly balls over the outfield fence and toward Sears Tower. And rather than surround the ballpark with a neighborhood, they destroyed it—getting the backing of the city to tear down nearly 100 residences in a poor, black section that sat in the way of New Comiskey. For being in the wrong place at the wrong time, evicted homeowners were each given $25,000 to set up camp elsewhere.

Gone with the homes were several businesses—including McCuddy’s Tavern, a favorite watering hole for White Sox fans traversing to Old Comiskey before and after games; it had been around so long that Babe Ruth frequented the joint when visiting with the New York Yankees. But New Comiskey would be death upon McCuddy’s, whose owners refused to resettle to a smaller spot over three blocks away from the new ballpark as requested by the Illinois Sports Facilities Authority (IFSA), the bureaucrats in charge.

You Can’t Build the Taj Mahal on a Sears Budget.

HOK Sport, the Kansas City-based architect hired to design New Comiskey, were no strangers to Philip Bess’ Armour Field concept; they had just wrapped on Pilot Field, a minor league facility in Buffalo considered the spark for the retro ballpark movement that would ignite with another of its projects, Baltimore’s Oriole Park at Camden Yards. But if HOK was salivating over the idea of giving New Comiskey the throwback look, the directives from the White Sox would prove frustrating.

Rick deFlon, HOK’s lead architect on the ballpark, admitted that he wasn’t handed a utopian exercise. He was restricted to the public budget set by the ISFA and the logistical demands of the White Sox, even as the team told him not to “turn your back on the old Comiskey.” “What you see,” deFlon told the Chicago Tribune, “is a real building that had the realities of budget and schedule play on it.”

Rate Field, originally called New Comiskey Park, during the final phases of construction in September 1990. Note the steepness of the upper deck and the view looking southeast toward the projects. (Jerry Reuss)

Some of Old Comiskey’s architectural touches would be retained in New Comiskey. Principal among these would be the arched openings spaced around the ballpark bowl—but unlike the old ballpark, the openings were covered with highly reflective glass which, along with beige-painted precast concrete etched with mild, abstract patterns, gave the overall structure the look of a sporty office complex. Worse, the structure—lacking embellishment at the top due to budget restraints—was largely hidden behind a series of switchback pedestrian ramps that interfered with what grace it had.

Inside, intimacy was hard to find. So were the players on the field for those sitting towards the top of the upper deck, an arduous ascent to a height so far up, you would have thought the White Sox would advertise for sherpas over ushers to assist fans to their seats. Someone did the math and discovered that the closest seat in New Comiskey’s upper deck was farther away from the field than the last row of upper deck at Old Comiskey. And it was much, much higher. The steepness of the upper deck, combined with Chicago’s famously strong winds, at times forced the White Sox to actually close portions of the level as a safety precaution. But fans did remark how cool it was to look down on a towering pop-up.

To be fair, New Comiskey Park did not open as a cold, unsightly blunder; that was left to the White Sox, who lost 16-0 to Detroit in their first and, still, worst shutout loss in Rate Field history. Architecturally, there was apt warmth to be found. The famous “exploding” scoreboard, conceived by Bill Veeck in 1960 to celebrate White Sox home runs with an arcade-like display of fireworks, casino-style lights and twirling pinwheels, was recreated. A cornucopia of bronze sculptures—nine at last count—featuring White Sox legends grace the back of the bleachers to provide fans with a history lesson. Nancy Faust, the team organist who would play for 40 years and be of such renown that they gave her a special bobblehead night, was retained from Old Comiskey. And for all it was worth, the infield dirt from the old park was transported over to serve the new one. But still, local architecture critics declared the ballpark a disappointment given the rich tradition of acclaimed structures within Chicago.

Rate Field’s “exploding” scoreboard, a homage to the Old Comiskey that goes into action whenever a White Sox player belts a home run. (Flickr—Ken Lund)

The White Sox’ horrible debut aside, New Comiskey was a big hit with the fans when it opened in 1991. An all-time franchise attendance record was shattered as 2,934,154 fans clicked the turnstiles, a mark itself that would be tipped in 2006 as spoils for winning the world title the year before. For the bulk of the 1990s, the White Sox matched the crosstown Cubs fan for fan and sometimes even outdrew them; they certainly out-won them in the standings, taking three divisional titles in their first 10 years at the new park. The venue even went Hollywood when, in My Best Friend’s Wedding, Julia Roberts tried to put the moves on Dermot Mulroney in the luxury suite of fictional White Sox owner Walter Wallace…though astute moviegoers had to wonder why the Lord of the White Sox would have his suite located way down the right-field line, next to the foul pole.

Jerry Reinsdorf, the non-fictional White Sox owner, scoffed at the criticism of New Comiskey. He didn’t want to hear about the mile-high spectators in the upper deck, or the endless parking lots that cut the ballpark off from outside humanity, or the lack of retroesque character that graced highly praised new ballparks elsewhere. Instead, Reinsdorf wanted to blame it all on the sour post-1994 strike atmosphere that left baseball fans turning their backs on the game, much the way the new ballpark turned its back on the Chicago skyline.

Okay, You Were Right.

At some point, around 2000, Reinsdorf and the White Sox finally experienced their come-to-Jesus moment and admitted that the ballpark could use some work. They hired a different architect (Dallas-based HKS, designers of the ornate Ballpark at Arlington), spent almost as much money ($118 million) as it took to build the entire venue and took seven years on a renovation that was undertaken bit by bit to keep distraction to the fans and players at a minimum. It may not have transformed the joint into Wrigley, but it was an improvement—a sorely needed one at that.

Some 2,000 new seats were planted in the lower deck, eliminating foul territory and bullpens previously hidden away from the fans, not to mention the managers keeping an eye on their relievers. That, combined with a heady reduction of field distance down the lines, made the ballpark come offensively alive after it had been originally branded fair for both pitchers and hitters; this was made abundantly clear when home runs totals shot up in the 2000s. Mike Cameron went deep four times in one 2002 game while, two years later, everyone contributed with a park-high 272 homers between the White Sox and their opponents—the most ever hit at a ballpark not named Coors Field.

This unique monument to the 2005 world champion White Sox, located in front of the formal main entrance, consists of bronze, granite and photographic impressions—all sitting on a base of personalized bricks. (Flickr—Courtesy Frederick J. Nachman)

The bleacher section was enlivened by more than just the extra opportunity to snag a home run ball. A multi-tiered party deck was introduced above the batter’s backdrop wall in center field, and over near left field a tri-level funhouse of baseball skills interaction called FUNdamentals arced out above the bleachers. All around the park, the concourses were beautified and, in the case of the club level, enclosed with climate control; and in a nod to Old Comiskey, the seats were repainted in dark green, but two were left in their original blue color: One behind left field where Paul Konerko’s grand slam in Game Two of the 2005 World Series landed, and the other over in right where Scott Podsednik’s walk-off shot in the same game fell.

The biggest—and by far the most imperative—change took place in the upper deck. The top eight rows consisting of 6,600 seats were chopped off; along with it went the somewhat worthless curved roofing that barely covered anything and had originally been painted with a hideous powder blue left over from the blasé Yankee Stadium renovations of the 1970s. Replacing it was a more expansive flat grandstand roof reminiscent of old Comiskey, giving the level badly needed intimacy and some old-time charm—though that was lost on the roughly 300 people whose view would be obstructed by the support posts that propped the roof up.

To pay for the makeover, New Comiskey Park was renamed U.S. Cellular Field, as the telecommunications giant paid $68 million for 20 years’ worth of naming rights. Predictably, fans frowned on the corporatization, with some still preferring to call the park by its original name. Most went with “The Cell,” while a few others with a sense of humor go with “The Joan”—in honor of former U.S. Cellular spokeswoman, actress and long-time Chicago-area resident Joan Cusack.

The rebranding of the ballpark to Rate Field late in 2016—shortened to Rate Field in 2025—generated even more disdain. Folks couldn’t help but chuckle at the use of the mortgage company’s logo—which features a red arrow going downward—displayed on the venue’s exterior. It wasn’t an optic that the White Sox, in the midst of a downward spiral on the field, really wanted to absorb.

The Chicago skyline as seen from Rate Field. Unfortunately, no one can see it from inside the ballpark; the White Sox feared cheap, wind-blown home runs and decided to orient the ballpark away from downtown. (Flickr—Jebb)

What’s Cool, and What Cools You.

The White Sox have added more kitsch throughout the years at Rate Field. The main entrance, which really isn’t one since many fans use the pedestrian ramps on the sides to get in, has been given prestige with the addition of a unique, complex sculpture honoring the 2005 world champion White Sox; nearby, a display of the day’s starting lineup (the nine batters plus the pitcher) is graphically shown with posters for each player side-by-side. Inside, there’s two “rain rooms” where fans seeking relief from the summer heat and humidity can cool off under a series of misters; for those who really want to get wet, there’s the Chicagoland Plumbing Council Shower—yet another carryover from Old Comiskey and the imagination of Bill Veeck—located behind the left-field bleachers. No word on whether the shower has hosted an unauthorized wet T-shirt contest in a city that gave birth to Playboy magazine.

More recently, the White Sox have installed a social media hangout called #SoxSocial Lounge on the lower deck, complete with monitors, charging stations and couches for fans to relax and text their friends as to what they’re missing on the field.

One thing is for sure at Rate Field: The White Sox will make it certain that you don’t leave the park on an empty stomach. There’s the aforementioned ChiSox Bar & Grill across 35th Street, featuring a basic menu of burgers, fries and ribs that’s quite inexpensive by ballpark standards; behind the right-field fence there’s the Miller Lite Bullpen Bar, which transcends a dive-like atmosphere by hanging out under the bleachers—though for a few bucks extra, you can snag an outside table right behind the chain-linked outfield fence that separates you from the right fielders; and in the more privileged levels, a good number of eateries are available including the Stadium Club, a full-bore restaurant that has a panoramic view of the park from near the right-field corner. The myriad of more common concessions encircling the ballpark come with titles evoking White Sox stars you may have forgotten (Bill Melton, Chico Carrasquel, Sherm Lollar, et al)—though this you must remember: This is Chicago. If you are a grown adult, never, ever eat a hotdog with ketchup.

The starting lineup for each White Sox game is posted outside Rate Field via graphic posters. (Flickr—Courtesy of Frederick J. Nachman)

We Like it Here.

Between the lines, the White Sox have always felt comfortable at Rate Field. Outside of them, not so much. This was especially true in the early 2000s when there was a troubling rash of modern-day ruffians who invaded the field from their seats down the right field line and beat up the nearest guy they could get to (the unlucky chaps in such instances included Kansas City base coach Tom Gamboa and umpire Laz Diaz). The Royals, who always seemed to be the visiting team when these fans behaved badly, threatened to boycott any future visits to the ballpark unless security was improved.

While other teams encourage fans to roam around their ballparks, Rate Field employs this rather mean-spirited policy of not allowing upper deck ticketholders anywhere else within the venue. (Flickr—Bari D.)

But back to between the lines. The White Sox have rarely stunk up the park with their performances (yes, besides losing 16-0 in that first game), with their worst season home record to date a not-so-heinous 36-45 in 2011. Not surprisingly, Frank Thomas, whose ascent to major league stardom coincided with the opening of New Comiskey, remains the ballpark’s all-time home run king with 263—just four ahead of equally popular White Sox slugger Paul Konerko. And while the improved hitting conditions have made it tough on White Sox pitchers over the years, it never bothered long-time team ace Mark Buehrle, who won 90 games at Rate Field—twice as many as the next guy—with two no-hitters including the park’s only perfect game, performed in 2009. (As a reminder that Buehrle’s perfecto came with help, there’s a simple typographical reminder atop the left-field fence that states “The Catch” to honor the sensational grab made in that game by White Sox outfielder DeWayne Wise.)

Fans seemed to have come to terms with Rate Field. Whether the surrounding residents have done the same remains a touchy subject, especially for the poorer, largely African-American communities that feel a sense of segregation that the ballpark wedged between them and the whiter, trendier neighborhoods to the north and west. Amid its basic criticisms, there is an apologetic tendency to give the ballpark a pass on the basis of bad timing, as if the White Sox were unaware of the impending retro ballpark craze started by Oriole Park at Camden Yards soon after its opening. But they should have taken the clues from their major league neighbors to the north at Wrigley Field and the architectural experts in their own backyard who dreamed of a dynamic integration of baseball, commerce and housing. Philip Bess, again: “There is a historic reciprocity between good city neighborhoods and good baseball parks.”

Reciprocity never had a chance with the White Sox. Rate Field was, and remains, a missed opportunity.

The Ballparks: Comiskey Park When you get your ace pitcher to design your ballpark, you’re going to get a pitcher’s park. And that’s what Comiskey Park was, extending the Deadball Era for decades as the Second City’s Second Team experienced little offense but an explosion of scandal, scoreboards and disco records for a lively and sometimes unruly South Side fan base.

The Ballparks: Comiskey Park When you get your ace pitcher to design your ballpark, you’re going to get a pitcher’s park. And that’s what Comiskey Park was, extending the Deadball Era for decades as the Second City’s Second Team experienced little offense but an explosion of scandal, scoreboards and disco records for a lively and sometimes unruly South Side fan base.

Chicago White Sox Team History A decade-by-decade history of the White Sox, the ballparks they’ve played in, and the four people who are on the franchise’s Mount Rushmore.