THE BALLPARKS

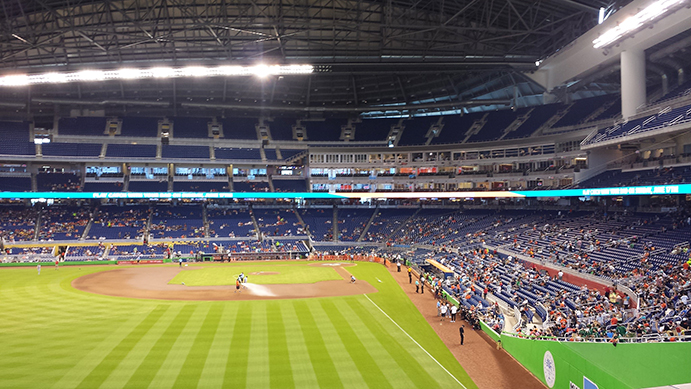

loanDepot park

Miami, Florida

(iStock)

Like a tropical alien cruise ship run aground within a low-income neighborhood, loanDepot park is the Colossal Cabana in Little Havana—an avant-garde baseball playground that might be confused for a modern museum of art, even if the curator was incurably cheap with his Marlins. The few fans who show up know they’ll be dry thanks to a retractable roof that shuts out the rain and howls of criticism from those who cursed the shady machinations behind its development.

When browsing through the historic Little Havana neighborhood west of downtown Miami, visitors might stumble upon the damnedest thing: loanDepot park, home of the Marlins. The web site for Populous, the renowned ballpark architectural firm behind the ballpark’s design, boasts that the venue is “where beauty and baseball collide”—but the real collision takes place outside, where loanDepot park’s decidedly ultra-modern combination of curved steel, sky-reflecting glass, sleek recesses and over-the-top art provides a staunch contrast to the culturally loud but structurally humble neighborhoods that surround it. It’s confusing enough that the ballpark’s formal name contains two words with lower-case initials and a capital letter stuck in the middle; loanDepot park and its surrounding environs, in the words of architectural critic Paul Goldberger, “coexist rather than connect.”

It’s not as if the Marlins haven’t tried to blend itself in with its neighbors, at least on a social level. The four garages that surround loanDepot park—rectangular six-level structures that appear to act as a protective buffer to the ballpark—feature street-level retail space on the outer perimeters, ideally for food marts, restaurants and bars, among other community-friendly stores. But most of them have “For Lease” signs slapped on the front doors, as they have from the day the ballpark opened. Such failure is the tip of the iceberg for a striking structure that has endured through enough trials and tribulations to fill a long page on a web site—such as the one you’ve started to read.

Which gets us back to loanDepot park being the damnedest thing. It’s beautiful, awe-inspiring and unlike anything seen among American sports facilities. It’s won numerous design awards and been well praised for its aggressive push to be environmentally friendly. Alas, loanDepot park is also the most vilified structure in the entire Miami metro area—primarily due to an owner who did everything in his power to make others pay for a ballpark that he would surely and purely profit from.

Give Me My Ballpark.

The merging of Baseball with the South Florida summer has always been a tricky proposition. While the game plays wonderfully in the spring, when the Grapefruit League holds sway and visitors happily thaw out miles away from the northern bergs they call home, it’s a different experience when the summer solstice hits. The heat and humidity are intensified well beyond a refreshing level, and while the seemingly daily late-afternoon rain cells provide relief, they do no good for any baseball game trying to get through nine innings.

When Major League Baseball awarded Miami with one of two franchises to begin play in 1993, it made the fatal mistake of not insisting on a new ballpark with some kind of covering—whether it be a retractable roof or a permanent dome. The man chosen to run the new ballclub, entrepreneur H. Wayne Huizenga, was initially content to plug the team into Joe Robbie Stadium, built primarily for football. Huizenga had his reasons; having bought the facility in 1990, he needed additional revenue to pay off the debt he inherited.

All was well in the Marlins’ first year, when three million fans officially poured through the gates. The following years would be less kind; the team wasn’t winning, and the devastating work stoppage of 1994-95 soured the mood—but worse than those two factors was the weather and the stadium. The brutal summertime heat and humidity were unlike anything Miami sports fans had to endure during a fall-time Dolphins football game, while Joe Robbie Stadium’s conversion to baseball, admittedly made easier on a logistical level due to its squarish shape, still made Marlins fans feel like second-class citizens with sightlines that were less than pleasing.

Huizenga was not a sports fan, but a businessman. He made his fortune through industries as varied as waste management, video rentals and auto dealerships. Now he eyed the South Florida sports scene. He already owned the Dolphins, and became the initial owner of the NHL’s Florida Panthers, which began play the same year as the Marlins. The Panthers rode a faster track to success, reaching the Stanley Cup finals in just their third season—and Huizenga capitalized on the hockey fever by convincing local politicians to build the team a new arena.

If the Panthers could get a new facility by winning, surely the Marlins could do the same, Huizenga thought. In 1997, he binged on free agents, bringing in outfielder Moises Alou, third baseman Bobby Bonilla and pitcher Alex Fernandez—joining an already sound roster that featured ace Kevin Brown and slugging outfielder Gary Sheffield. The 1997 Marlins weren’t the 1927 Yankees—at least in the regular season, finishing at 92-70—but they gained entry to the postseason by virtue of the wild card spot, upended the favored San Francisco Giants and Atlanta Braves in the National League playoffs, then grabbed the World Series trophy in a thrilling seven-game triumph over the Cleveland Indians. We won it all, Huizenga proclaimed—now, give me my ballpark.

The City of Miami and Miami-Dade County said no. They had little public money to spare because, in part, much of it was already being used to build the Panthers’ arena—not to mention another one for the NBA’s Miami Heat. In a fit, Huizenga announced he was selling the team—complaining that even if he sold out Pro Player (formerly Joe Robbie) Stadium every game, he’d still lose $15 million—and tore down his championship roster as quickly as he built it. With his glut of All-Stars traded away, the skeletal Marlins of 1998 defended their world title by losing 108 games.

An aerial view of the Marlins’ first home, which has undergone numerous facelifts and name changes; it currently goes by the name of Hard Rock Stadium. Though built in 1987 with football in mind, the facility was made adaptable for baseball—but too many rain delays and a lack of revenue streams made financial survival highly difficult for the Marlins. (iStock)

0-for-Henry.

After the Marlins’ horrendous 1998 campaign, Huizenga made good on his vow to sell the team. Buying was John Henry, a 48-year-old commodities trade broker from Boca Raton who, unlike Huizenga, had a passion for the game, having grown up in the Midwest listening to St. Louis Cardinals radio broadcasts and yearning to be the next Stan Musial.

Henry was polite, humble but honest, telling local political leaders that he didn’t buy the Marlins to keep them at Pro Player Stadium. He backed off an early promise to fund a new ballpark himself, lobbying city and county officials toward putting up the lion’s share of funding. Henry came up with creative budgetary solutions; at one point, he suggested a scheme where a publicly-built ballpark would yield 90% of the Marlins’ profits back to the community. He then considered taxing Miami’s thriving cruise industry at a rate of four bucks per passenger, per day—a plan trashed as a “predatory tax” by Florida Governor Jeb Bush and “absolutely preposterous” by cruise line officials. The response to any public ballpark financing from city and county was lukewarm at best; the Miami Herald’s Greg Cote said specifically of the county, “Miami-Dade is only slightly more likely to build (Henry) a ballpark than it is to fund a downtown parade to celebrate Fidel Castro Day.”

By December 2000, however, Henry twisted enough arms within Miami-Dade County to agree on a proposal for a 40,000-seat ballpark with retractable roof just north of downtown, costing $385 million. The Marlins would pitch in $72 million, on top of $118 million in county hotel taxes and $73 million in ticket/ballpark garage surcharges. All that was needed to complete the deal was to convince the Florida State Legislature to gift $122 million through tax breaks to the Marlins. On the last day of the State session in May 2001, the measure passed the House—but the Senate never got around to consider the bill before the clock ran out.

Back to Square One, Henry struggled to regroup. The Herald’s Mike Phillips referred to the Marlins as a “dead man walking.” As the Florida tourism industry tanked late in 2001 in the aftermath of the 9-11 terrorist attacks, Henry folded. In a sweetheart deal with MLB, he traded in his three-year ownership of the Marlins for partial rule in Boston with the high-powered Red Sox.

Here Comes Trouble.

With Henry departing, the Marlins were given over to Jeffrey Loria, whose Montreal Expos were being considered by MLB for contraction. (They would eventually relocate to Washington.) Marlins fans crossed their fingers that Loria wouldn’t alienate Miami the way he did Montreal, where he constantly rubbed fans, players and politicians the wrong way and all but ran the franchise into the ground. MLB certainly had him on a leash, or perhaps puppet strings; he was essentially ordered by the league not to talk new ballpark for roughly a year after he bought the team for $158 million—$38.5 million of which was paid through a loan from MLB. Loria thus obeyed and focused on getting his team to win—which it did in just his second year running the Marlins, again lucking out through the wild card and getting hot at the right moment to defeat the almighty New York Yankees in the World Series.

But maintaining success while playing at Pro Player Stadium, which H. Wayne Huizenga still owned and sucked most of the revenue from, proved a massive challenge. Through his first five years at the helm in Miami, Loria lost up to $20 million annually—or so he claimed, since the team never opened their books for outside sources. Season attendance dropped to as low as 818,000. Team payrolls were cut to the bone; by 2006, the total payout to the active roster was an embarrassing $14 million—half of what the Tampa Bay Devil Rays, #29 on the list, was doling out. Even contracts were contingent on a new ballpark; third baseman Mike Lowell once signed a four-year, $32 million deal that could be voided after two seasons if no new venue was agreed to.

Midway through 2003, MLB lifted its gag order on Loria, and discussions began anew on a ballpark. He would find the road to loanDepot park as windy and pothole-ridden as had Huizenga and John Henry before him. Through the next four years, the ballpark saga dragged on and on and on, with more stops and starts than rush hour on Interstate 95. Numerous sites were discussed; there wasn’t a single large chunk of available land between Ft. Lauderdale and the northern edge of the Keys that wasn’t considered. Deadlines threateningly ending in “or else” were tossed from all sides, elapsing without consequence. Potential deals, agreed to at the city and county level, were knocked down at the 11th hour by state politicos. At times, Loria and the Marlins threw their hands in the air and began chatting with officials in Las Vegas and San Antonio about a possible move.

This view of loanDepot park, behind the third-base stands, shows many of the structure’s integrated materials as work. Much of the exterior consists of glass, which reflects Miami’s tropical skies and gives the structure a lighter, more airy presence. The orange letters semi-buried into the ground along the walkway is part of an artistic tribute to the Orange Bowl, torn down to make way for the ballpark. (iStock)

Goin’ Orange.

A break finally came in the Summer of 2007. The University of Miami football team, the sole occupant of the Orange Bowl in the north portion of Little Havana, announced that they would relocate to Joe Robbie/Pro Player Stadium—now going by the name of Dolphin Stadium. It was good news for H. Wayne Huizenga—more revenue—and even better news for the Marlins, because it freed up a total of $88 million that the City of Miami and Miami-Dade County had budgeted to upgrade the 72-year-old facility. The theory now went that the money could be used instead to fill the budget gap on a Marlins ballpark—and this time, there would be no need to get a final financial push from the State Legislature.

This wasn’t the first time that the Orange Bowl had been thought of as a possible ballpark site. One earlier proposal had it being reimagined as a multi-purpose venue with a roof, while another had a baseball-specific facility side-by-side with the existing stadium, which would be truncated to make room. It even had some baseball heritage to speak of; the minor-league version of the Miami Marlins played select games at the facility from 1956-60, once drawing 57,713 for a game featuring legendary pitcher Satchel Paige.

But now, the Marlins had the opportunity to have the site all to themselves. While the Orange Bowl wasn’t the Marlins’ idea spot for a ballpark—they fancied something closer to downtown or the waterfront, not something plunked in the middle of a low-income neighborhood—they had long since concluded that there were no other alternatives.

While demolition crews did what Bruce Dern failed to do with the Goodyear blimp in Black Sunday—bring down the Orange Bowl—the City of Miami and Miami-Dade County voted to, at long last, officially approve the ballpark in February 2008. The terms: A $515 million facility featuring a retractable roof, with the Marlins pitching in $155 million while the city and county paid the rest mostly through “bed” (hotel) taxes. An additional $94 million would go toward four parking garages that would surround the ballpark. Initially, the plan even called for an adjacent 25,000-seat soccer stadium for an expansion MLS franchise, but that was later dropped. Finally: The agreement called for the team to be rebranded as the Miami Marlins.

Miami Mayor Manny Diaz was as relieved as he was happy from what had seemed an exhaustive, neverending quest. “This is probably the hardest deal I’ve ever worked on in my life,” he said. Meanwhile, Jeffrey Loria saw a future full of delusionary grandeur, proclaiming that the new ballpark “will allow us to compete year after year for titles, pennants and World Series championships.”

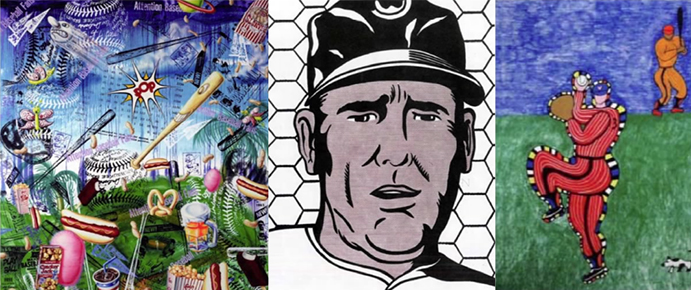

Marlins owner Jeffrey Loria, who made his fortune as an art dealer, embraced the idea of giving loanDepot park a modern museum-like vibe. Art from inside the ballpark includes (from left to right), Play Ball! By Kenny Scharf, Baseball Manager by Roy Lichtenstein, and Baseball by Niki de Saint Phalle. Only Scharf’s painting was commissioned for the ballpark.

Ballpark…or Gallery?

As a man who made his millions as an art dealer, it only seemed natural that Loria would push the envelope on ballpark design. He wasn’t the slightest bit interested in the fading retro trend, nor Miami’s revered (but also nostalgic) Art Deco styles. What Loria sought instead was something akin to a museum of modern art.

Long before Marlins Park—as the ballpark would initially be named—was approved by the politicians, Loria recruited the renowned ballpark architect firm HOK Sport (later Populous) to help realize his visions. Taking the lead on the HOK side was Earl Santee, who was instrumental in the creation of highly praised retro ballparks such as Baltimore’s Oriole Park at Camden Yards and Pittsburgh’s PNC Park. Been there, done that, Santee likely thought, which only made him feel more liberated when Loria approached him on conceptualizing something completely different.

Unlike the Marlins, Santee had always fancied the idea of a Little Havana ballpark, spending much of his early time absorbing inspiration within the culturally radiant neighborhood. But he was open to Loria’s more modern bent and, working with a staff of 30 people, put together a book of sketches as a presentation to the Marlins’ Lord. At some point, Santee caught up with Loria in London (of all places) and they shared their thoughts: Santee with his sketchbook—and Loria with a napkin showing his own idea of the ballpark. “Run with this,” Loria basically told him.

There were numerous concepts that made it to the presentation stage, including one that evoked a cruise liner and another resembling a curvy painter’s palette. But those ideas were merely sacrificial time-killers as it became apparent that the third concept—the one that would see its way to reality—was the clear winner.

Marlins Park would be, as Santee later described to The New Yorker, “quintessentially Miami.” It’s a contemporary mix of bright white stucco and colored glass, wrapped by cool gray metal panels that thin out from the west entrance to the east plaza, itself towered over by six sliding glass curtains that reveal, for fans on the inside, a breathtaking view of downtown Miami behind the left-field bleachers.

loanDepot park is described by Populous as an “abstract interpretation of water merging with land,” but it’s really more a case of cutting-edge architecture merging with sky. The various glass elements—especially the glass curtains, when closed—beautifully reflect Miami’s tropical, cumulus-dotted skies, giving the ballpark an airy, almost transparent appearance that optically minimizes its bulk.

Loria tapped into his knowledge of the arts to decorate loanDepot park. Using the late Spanish modern artist Joan Miró as an influence, he developed a flamboyant four-color scheme to identify various sections of the ballpark; yellow on the first-base side, red on the third-base side, a brilliant light green on the outfield wall, and rich, deep blues for behind home plate and all the seats throughout the venue. In the concourses, Loria installed reproductions of existing baseball art as well as new works he commissioned, creating a colorful quasi-gallery for fans to stroll through. Outside in the main entry plaza at the ballpark’s west end, a matrix of walking paths was decorated with splashy color tiling by Venezuelan artist Carlos Cruz-Diez. And on the other side of the facility, the east-end bleacher entry area was littered, literally, with giant, 3-D sans serif letters that mimicking the old signage atop the Orange Bowl. The idea behind the random collection, entitled “A Memorial Bowing” by artist David Arsham, was to envision what would happen if all the letters used in the old stadium fell to the ground.

So, You Had the Cash All Along.

While Loria focused on paint swatches and art portfolios, the local public focused—and fumed—over the sweetheart deal the Marlins received from the city and county on the new ballpark. Much of the citizens’ wrath was understandable. Because Miami-Dade County didn’t have enough cash in the kitty to finance Marlins Park, it had to take out $409 million in loans, which through interest would balloon to a staggering $2.4 billion by the time the last payment would be made in 2049. Additionally, the ballclub would essentially pocket all revenue for Marlins and non-Marlins activities (including concerts and sporting events) held at the ballpark while the city and county got relative leftovers—$2.3 million in annual rent from the team with a locked-in 2% increase each year, and 16 days per year to use the venue however they saw fit.

Though the ballpark was officially approved in the Spring of 2008, numerous nuisances delayed groundbreaking for nearly a year. Unions wanted this. Minority businesses wanted that. City and county police departments armwrestled over who would patrol the park. One Miami city commissioner wouldn’t vote ‘yes’ on the ballpark until the Marlins pledged to share the profits from any sale of the team within the ballpark’s first 10 years (he got it), while another held back her aye until she got $500 million in redevelopment funds for her district (she got it).

Most irritably, the Marlins had to absorb a lawsuit from Norman Braman, a wealthy local auto magnate, former NFL (Philadelphia Eagles) owner and well-known anti-tax rabble-rouser, who insisted on a public vote for the ballpark and an opening of the Marlins’ books to prove the relative poverty they pled. A judge ultimately knocked down the suit, with a statement that was music to the Marlins’ ears: “Retaining a professional baseball team in Miami satisfies a paramount public purpose.”

Braman was not alone in pursuing an accounting analysis of the Marlins’ finances. During negotiations, the city and county continuously badgered the team to probe its books; even a lawyer defending the Marlins on the issue admitted that he wasn’t given access to the records.

As the Marlins refused to release their financials, Deadspin did it for them. In the summer of 2010, the snarky sports website actually did some investigating and hit paydirt, clandestinely given evidence that the team received $92 million in MLB revenue sharing—resulting in handsome profits that would have allowed it to contribute much more funding for the ballpark. The leak, making nationwide news, infuriated everyone outside of Loria’s orbit—and those within, for a much different reason. Outspoken Marlins team president David Samson, Loria’s Number Two, called the leak a “crime” and insisted that any profits would likely go toward paying off team debt. Samson also chopped down any suggestion that the Marlins were ready to renegotiate in the wake of the Deadspin revelations, telling the Miami Herald, “A contract is a contract.” The Deadspin controversy was enough to attract the attention of the Securities and Exchange Commission, which ultimately opened an investigation into the team’s accounting methods; the agency kept the case open for five years, but then closed it after finding no wrongdoing.

Braman’s rustling of the political leaves did lead to a consolation prize; he forged a recall vote on Miami-Dade County Mayor Carlos Alvarez, who voted yes on the ballpark; in March 2011, 88% of the public voted no on Alvarez, knocking him out of office.

A view of the eye candy beyond left field in loanDepot park’s early years, when it was known as Marlins Park. Open sliding doors reveal a gorgeous view of downtown Miami, while the controversial home run sculpture named Homer hangs out behind left-center. Homer was moved to outside of the ballpark in 2019 after new Marlins executive Derek Jeter expressed genuine hatred for it. (Flickr-Steve)

Let the Kitsch Begin.

Perhaps pressured by the Deadspin leak—or simply in anticipation of abundant new ballpark revenue—the Marlins went all in for the opening of Marlins Park. They uncharacteristically opened their checkbook and loaded up on free agents, signing veteran starting pitchers Mark Buehrle and Carlos Zambrano, flashy shortstop Jose Reyes and closer Heath Bell; they even made a play for superstar slugger Albert Pujols, before he agreed to a megadeal with the Angels in Anaheim. Also brought in was a proven, if blunt, new manager in Ozzie Guillen, seven years removed from winning the World Series for the Chicago White Sox. The team rebranded, introducing a new logo and uniform scheme. Season ticket sales shot up from 2,500 the year before to 15,000.

The Marlins carefully scheduled a series of ‘dry run’ exhibitions in March 2012 involving high school teams, college teams and finally the Marlins themselves, each game with increased capacity, to help break in Marlins Park while ironing out any of the anticipated wrinkles that came with a new ballpark.

For the first official regular season game at Marlins Park, the team spared no expense. Jose Feliciano sang the National Anthem. Boxing legend Muhammad Ali, fighting Parkinson’s Disease, threw out the ceremonial first pitch. Miami-style showgirls flocked in colorful feathers escorted Marlins players to the baseline during pregame introductions. The lone disappointment on the evening would be the Marlins themselves, who didn’t get their first hit until Jose Reyes’ leadoff single in the seventh off the St. Louis Cardinals’ Kyle Lohse; they eventually lost, 4-1.

Fans marveled at the new palace and the more unique attractions it provided.

Under the left-field bleachers, a touch of nightlife was applied with the addition of The Clevelander, co-owned by the popular namesake South Beach hotel/club. For $75, one could hang out, drink (at additional cost), and swim in a mod-looking pool under the watch of female dancers clad, at times, in nothing more than bikini bottoms and body paint—all to prove that baseball had come a long way from the days of Ebbets Field.

Between the two dugouts, the backstop featured two aquariums—one 24 feet long, the other 34—each holding up to 450 gallons of saltwater. Hitters dreaded the idea of screaming a line drive off one of the tanks and rupturing it like the one at the Prague restaurant in Mission Impossible—but the Marlins made sure the fish were safe by protecting them with 1.5-inch glass, thick enough to be ball-proof. That theory was challenged in 2017 when the Marlins’ J.T. Realmuto fouled a line drive that cracked the tank; it was patched up without major incident.

One group naturally not happy with the tanks was PETA (People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals), who feared that the aquatic occupants would be stressed by the ballpark’s “loud crowds, bright lights and reverberations.” It suggested several alternatives: Fake fish made of blown glass, robotic fish, or hi-def images of sea animals. David Samson politely dissented, stating, “I guess that’s a philosophical issue.”

Undoubtedly the new ballpark’s most talked-about art attraction, placed behind the left center-field fence, was Homer—a 73-foot-tall, $2.5 million thimble-shaped sculpture by Red Grooms, labeled the “pop maestro of kitsch” by the New York Times. Whenever a Marlins player belted a round-tripper, dolphins and seagulls circled about, pink flamingoes danced, water shot up and neon flowers pulsated with colorful light. It looked like a Terry Gilliam cartoon from Monty Python gone mad; some critics probably were upset that the display didn’t end with a giant foot squashing the whole thing. “Kaleidoscopic, playful and bizarre,” wrote Peter Richmond for ESPN the Magazine, in one of Homer’s kinder reviews. Others were a bit harsher. “A home run sculpture fit for a Timothy Leary class at Harvard,” The Miami New Times wrote. “A cheap design for a miniature golf course,” wrote ESPN’s Jim Caple.

The beautiful main entry to loanDepot park, on the structure’s west side. The large, upper panel of the ballpark’s retractable roof rests on tracks held up by supports that split and curl away like a tree trunk. (iStock)

Made in the Shade.

The most refreshing aspect for Marlins Park fans was the climate, thanks to the venue’s retractable roof. Weighing 8,300 tons, covering 17 acres and spanning 560 feet, the massive steel roof consists of three panels, can be operated independently to produce “micro shading effects,” and can open or close in roughly 15 minutes. It can also withstand hurricane-force winds of up to 137 MPH—a scenario that was tested in September 2017 when Hurricane Irma struck South Florida; the roof held with only miniscule damage.

Here’s the thing about the roof: When asked to close it, the operator in charge presses a button—and has to keep it pressed until the operation is done, 15 minutes later. “It’s not the most physically demanding job,” said Mike McKeon, the man at the switch, told the South Florida Sun Sentinel in 2018. But he did admit, “Sometimes I do have a scratch or have something else I’m doing, I’ll try and switch fingers.”

Fifteen minutes sometimes isn’t quick enough to dodge Miami’s petite rain cells that commonly appear out of nowhere. Downpours sometimes sneak through loanDepot park’s open roof; embarrassingly, one took place on Opening Day 2015 with a good portion of a rare sellout crowd got soaked.

The roof has been a godsend for the Marlins and their fans, guaranteeing pleasant, dry conditions under the roof when needed—in stark contrast to the 25 games per season, on average, interrupted by rain delays at Joe Robbie/Pro Player/Dolphins/Hard Rock/etc. Stadium. Furthermore, the beauty of the roof is that when opened over the ballpark, the larger, upper panel rests outside above the main west entrance—shielding arriving fans from the hot afternoon sun.

Finally, loanDepot park’s roof is topped by a thermoplastic white membrane to reflect heat, rather than absorb it. This is just one element of the ballpark’s relatively light carbon footprint, which has earned the facility Gold LEED status from the U.S. Green Building Council. loanDepot park is praised for its reduced water usage, lack of CFC-based refrigerants and vigorous recycling programs. The ballpark’s support beams are made of concrete recycled from the ruins of the Orange Bowl; the flooring in the clubhouses includes materials from recycled sneakers.

The interior of loanDepot park, looking from the left-field bleachers before the start of a May 22, 2016 game between the Marlins and Washington. Note the absence of any fans in the upper deck; with attendance plummeting, the Marlins a few years earlier had decided to close off the entire upper level for certain games. (Flickr—Jenni Konrad)

You Lost Us at Fidel.

Most honeymoons between the fans and a new ballpark last around a couple years. Marlins Park’s lasted barely a couple of weeks. The Marlins faced an immediate PR nightmare when new manager Ozzie Guillen was quoted in Time magazine as praising Cuban dictator Fidel Castro—an absolute no-no for anyone employed within a neighborhood full of Cuban exiles. After a promising 31-23 start to the year, the Marlins cratered to a last-place, 69-93 finish in the National League’s Eastern Division. The season’s disastrous second half ate away at the gate; the Opening Day sellout was one of just two the Marlins drew for the entire year. Of the 2.2 million tickets sold by the team in 2012, only 1.4 million were actually used. That latter figure was barely half of what the Marlins had targeted. David Samson called the results lower than the “worst-case scenario.”

Even worse, Jeffrey Loria went back to being Jeffrey Loria of pre-Marlins Park infamy. After the season, he threw in the towel on his big-budget experiment and went full Connie Mack, trading away five of his top players (including Mark Buehrle, Jose Reyes and pitcher Josh Johnson) to Toronto for seven no-namers and prospects—beginning a process in which his team payroll would be slashed by nearly two-thirds.

Fans, politicians and taxpayers couldn’t contain their anger. Local newspaper columnists, almost in unison, pled with MLB to strip Loria of the franchise. Baseball fans were polled and picked Loria as the second most hated man—behind Fidel Castro. “He would need a pickax and miner’s helmet to find his subterranean approval rating,” the Miami Hearld’s Greg Cote wrote of Loria. Samson was equally pummeled by HBO’s Bryant Gumbel, who asked him point-blank to his face: “Where’s the evidence that the light at the end of the tunnel isn’t a train that’s coming to hit you?”

For their sophomore season at Marlins Park, the talent-deprived Marlins were every bit as bad as feared, losing 100 games for the second time in their existence. Two-thirds of the season ticket holders from the new ballyard’s inaugural campaign bailed out, and the Marlins didn’t sell out a single game; they resorted to Groupon to fill many of the 34,439 seats occupied for the season’s home opener. It got so bad, the team decided to close off the entire upper deck for select weekday games. Officials who gave thumbs’ up for the ballpark began to regret their votes. Those who voted yes or no were afraid to show up for a game, fearful that their appearance would be read as tacit approval of the facility in the taxpayers’ eyes.

Desperate for additional revenue, the Marlins aggressively sought to fill the off-days at Marlins Park with non-baseball events. There were the obvious takers: Big-name concerts, soccer exhibitions, college football bowl games and boxing bouts. There were also fundraising events, trade shows, a sermon by televangelist Joel Osteen that drew 40,000, a high school graduation ceremony that featured Vice President Joe Biden as the keynote speaker and, perhaps the trickiest of all, the “Race of Champions”—an event in which A-list auto racers from various genres competed on two separate but interconnecting tracks somehow embedded within the frame of the field.

Perhaps the most enthusiastic gathering for any event at Marlins/loanDepot park was a baseball game…not involving the Marlins. In 2013 and 2017, the World Baseball Classic held games at Marlins Park and featured contests between the United States and Dominican Republic, drawing jam-packed crowds—most of them rooting for the D.R., proving that soccer wasn’t the only sport where the U.S. national team felt like a road team on its own turf. The 2017 matchup between the two countries drew 37,446 fans—larger than any crowd the Marlins have ever drawn, with no no-shows—as rabid followers for both sides waived flags and screamed their guts out. Maybe if Jeffrey Loria had just signed all the D.R. players to the Marlins, his troubles would have been over.

The Marlins’ Giancarlo Stanton squares up before receiving a pitch in 2015. The fences at loanDepot park have been moved in twice since its 2012 opening, but that was of little concern for the powerful Stanton, who often hit them well over the wall. Stanton is the only player with over 100 home runs at the ballpark; no one else is even close. (Flickr—Corn Farmer)

Giancarlo and El Niño.

Arising from the ashes of the Marlins’ first few pitiful years at Marlins Park were two genuine baseball gems who gave Miami baseball fans pure justification to table their fury at Loria and enjoy a game at the new ballpark.

Giancarlo Stanton predated Marlins Park by a couple of years, but he made the new ballpark his own. Baseball’s more mortal hitters may have complained of the venue’s spacious outfield dimensions—especially from left field to center, where the fence mostly sat back beyond 400 feet from home plate—but Stanton was no mere mortal. Wielding massive muscular punch, the 6’6”, 245-pound slugger turned Marlins Park into a Little League facility with his supersonic exit velocities and tape-measure home runs. In 2013, the Marlins as a team hit an all-time Marlins Park-low 36 homers, but Stanton was responsible for 15 of them; a year later, he led the NL with 37—with 24 of them deposited over (or well over) the ballpark’s lime green walls.

That the Marlins eventually moved the center-field wall 10 feet in and shortened its height in was of no consequence to Stanton. In 2017, he punched out 59 homers—the most by any major leaguer during the 2010s—with 32 of those at Marlins Park. Loria went against personal tradition and gave Stanton, at the end of 2014, a 13-year, $325 million contract unparalleled in major league history—though universal opinion set the chances of Stanton serving out the totality of that deal in a Miami uniform as very weak.

While Stanton quietly but forcefully went about his job annihilating fastballs, Cuban émigré Jose Fernandez went about his of blowing away opponents with his heater. Debuting at age 20 in 2013, the flamboyant Fernandez—nicknamed El Niño for his jovial, child-like personality—was a breath of fresh air in the Marlins Park clubhouse and a wonder on the mound, winning NL Rookie of the Year honors and setting a major league mark by posting 17 home wins without a loss to start his career. Along with Stanton, Fernandez made it fun to go to Marlins Park for the first time beyond what Homer, the Clevelander and all that modern art had to offer.

The brilliant vibe that Fernandez brought to the Marlins came to a heartbreaking end on the morning of September 25, 2016. Boating with two friends shortly after midnight, Fernandez accidentally struck a jetty near Miami Harbor at full speed, ejecting and killing all three. The news devastated the Marlins, and baseball in general; Miami manager Don Mattingly could not fight off the tears when speaking on behalf of the players in a midday press conference. A day later, the Marlins returned to the field before a Marlins Park crowd of 26,833 with all players wearing Fernandez’s #16 in his honor. Leading off the first, light-hitting Miami outfielder Dee Gordon belted a rare home run; he raced around the bases with tears streaming down his eyes and vanished into the clubhouse—unable to manage the crushing emotions of the previous 36 hours.

The anguish cast over the Marlins in the wake of Fernandez’s death became even more sobering when it was learned that the ace pitcher had cocaine and alcohol in his system at the time of his death. Though the Marlins had evolved from the awful unit of three seasons earlier, they would have to emotionally rebuild. Loria couldn’t do it; within a year, he sold the Miami Marlins.

Derek and the Dominoes.

For Marlins fans, the news of Loria’s exit must have felt like Liberation Day—especially after it was learned that Derek Jeter, the popular, recently retired Yankees shortstop, would be the action man making the moves on behalf of new majority owner, New York businessman Bruce Sherman. But the new regime’s early maneuvers evoked that scene in Bananas where the revolutionary Latin savior greets his citizens for the first time and tells them that, from here on out, they must speak Swedish and wear their underwear on the outside.

One of Jeter’s first moves was to order David Samson, the team’s outgoing president, to fire four “special assistants”: Hall of Famers Tony Perez and Andre Dawson, 2003 World Series-winning Marlins manager Jack McKeon, and even Mr. Marlin himself, Jeff Conine. Shortly afterward, the Marlins notified a front office employee of his dismissal while he lay in a hospital bed fighting colon cancer. The new owners wanted nothing to do with the memory of Jose Fernandez, emptying out his clubhouse locker (left occupied as a memorial) and squashing early movement on a sculpture of him at Marlins Park—likely because of the drug/alcohol angle related to his death. Jeter and Co. also decided to practically start from scratch with the roster, leading to the offseason trading of Giancarlo Stanton (to the Yankees) and two other promising young outfielders—Christian Yelich and Marcell Ozuna.

The new Marlins also didn’t embrace the Loria’s ballpark kitsch; over their first few years, they sought a more standard in-game experience. In a mutual agreement with the Clevelander, the saucy nightclub behind the left-field fence was shut down and remade into a more traditional ballpark bar and lounge. Real grass was eliminated for synthetic turf called B1K (short for ‘batting a thousand’) to save on water, sod maintenance headaches and, of course, money. And the ballpark changed its name when the team came to an agreement with California-based mortgage lender loanDepot to include its name in the venue’s title.

Most topically, Jeter made no bones about his feelings toward Homer, Red Grooms’ jazzy home run machine; he hated it, and wanted it gone. The City of Miami initially stiff-armed Jeter against the idea, saying it was public art in a publicly built facility. Grooms heavily lobbied against the move—but the Marlins countered by claiming that the sculpture didn’t shout “Miami” but, by Groom’s own admission, “Daytona.” Eventually, a compromise was reached; Homer was escorted out of the building, placed outside at loanDepot park’s southeast corner near David Arsham’s scattering of giant Orange Bowl letters. Back inside, Homer’s spot has been taken over by another special gathering place, the multi-tiered AutoNation Alley group lounge.

As anticipated, the first few years of the Jeter Era in Miami went about as unwell as expected. The team lost 98 games in 2018, and a depressing 105 a year later; in both seasons, they officially drew just over 810,000—the first official sub-million draw by an MLB team since the lame-duck, 2004 Montreal Expos. At least the new Marlins were being honest with the paid gate totals; the Loria regime counted ticket giveaways—or about 50% of those who showed up—as part of their attendance figures.

Finally, in the ninth year of loanDepot park’s existence, the Marlins produced their first winning record—though because of the COVID-19 pandemic, nobody was allowed to come to the yard and enjoy the team’s short-season 31-29 performance. Cardboard cutouts and roaming, masked photographers would have to do as witnesses.

This Google Earth image shows one of loanDepot Park’s four garages; each contains art using plastic white discs to create images of people looking through chain-linked fencing. It seems an apt metaphor for the low-income residents surrounding the ballpark, all of them taxpayers who weren’t allowed any say on the building of the facility. (Google Earth)

Same as It Always Was.

To the end and beyond, Jeffrey Loria stuck it to the taxpayers. When he sold the Marlins to Bruce Sherman and 13 other investors for $1.2 billion—after paying $158 million to buy the franchise in 2001—the local officials reminded him that he owed them 5% (or $52 million) of the net profit, per the terms of the ballpark deal. Incredulously, Loria said he made no such profit—claiming he actually lost money on the deal. Everybody knew the game Loria was playing. “You can’t tinker with gross profit,” Jay Rosen, a Miami business lawyer, told the Miami Herald. “But with net profit, it’s gross profit minus—and it could be almost anything under the sun.” Early in 2021, the two sides came to an agreement; Loria agreed to pony up $3.637 million to the City of Miami, while Miami-Dade County received $563,000. Small change, given the hundreds of millions still owed by taxpayers to pay off the budget loans through 2049.

It’s possible at some point that the Marlins will finally become a powerhouse and make loanDepot park relevant with sellout crowds and pennant fever. The architects and artists who labored their souls to make the ballpark one of baseball’s most fabulous deserve nothing less. Perhaps the same could even be said for Jeffrey Loria, whose own vision admittedly must be applauded. But you can’t blame the fans, taxpayers and politicians for shaking their fist at a man who took land and money with relatively little cash from his own pocket before spitting back at their shoes.

When loanDepot park was being built, it was said that the surrounding neighborhood, with its substandard median household income of $27,000, would be the better for it. Miami Mayor Manny Diaz said in 2009 that hotels, restaurants and retail would be built around the park. A Marlins exec gave an even dreamier assessment, telling ESPN’s Peter Richmond that “the next growth in Miami will move toward the ballpark.”

There has been no growth, no gentrification and no evidence of any effort by the Marlins to engage with the Little Havana community. Unlike the environments around other new ballparks in San Francisco, Denver and Washington (among others), the neighborhood surrounding loanDepot park is essentially the same as it was when it opened in 2012.

In each of loanDepot park’s garages that tower across the street from the area’s far more humble residences, there’s one more piece of art conceived by Jeffrey Loria. It consists of a large chain-linked fence dotted with white plastic discs to create images of young people looking…through a chain-linked fence. The irony of these visuals is hardly lost on many of the ballpark’s neighbors—to say nothing of the taxpayers.

It is the damnedest thing.

Miami Marlins Team History A decade-by-decade history of the Marlins, the ballparks they’ve played in, and the four people who are on the franchise’s Mount Rushmore.