THE BALLPARKS

Oracle Park

San Francisco, California

(Chris Ayers)

In the annals of baseball, home runs have landed in places as varied as apartments, auto dealerships and snowbanks. But hardly ever into water. Oracle Park, with its glorious views of San Francisco Bay, has become the first park in the majors to allow a crushing drive to make a splash landing, past the slim right-field bleachers and into aptly-named McCovey Cove—where a potpourri of aquatic adventurists anxiously await their chance to scoop up a souvenir.

Notice has been served to the world-famous landmarks of San Francisco. The Golden Gate, Fisherman’s Wharf, Alcatraz, Lombard Street, and the Presidio now have serious competition, located 309 feet away from the motion of a left-handed slugger’s bat. It is here, at the right-field corner in Oracle Park, where fans converge—whether seated, walking the concourse, peeking for free behind arched openings, or boating behind in McCovey Cove—and breathlessly wonder to each other, “If he connects, will it reach the water?”

Notice has been served to the world-famous landmarks of San Francisco. The Golden Gate, Fisherman’s Wharf, Alcatraz, Lombard Street, and the Presidio now have serious competition, located 309 feet away from the motion of a left-handed slugger’s bat. It is here, at the right-field corner in Oracle Park, where fans converge—whether seated, walking the concourse, peeking for free behind arched openings, or boating behind in McCovey Cove—and breathlessly wonder to each other, “If he connects, will it reach the water?”

The “splash hit” may be a prime selling point at Oracle Park, the gorgeously sterling home of the San Francisco Giants, but there is so much more to behold in what may be the most feel-good ballpark to open since Oriole Park at Camden Yards.

Romantically nestled into 13 petite acres at the south end of the San Francisco waterfront, Oracle Park consists of a tight steel-and-brick framework that blends in perfectly with the historic facades of the surrounding China Basin district, which only 20 years earlier was an apprehensive place to walk—day or night.

Today, fear is absent. Amid blocks of trendy restaurants and upscale townhouses, the area around Oracle Park is bristling hours before the first pitch. Fans eat and drink alfresco, watch a giant tanker float by in the bay, or catch batting practice in seats as close to the field as any in baseball. This is the perfect moment for Giants fans, and this is their perfect ballpark; easy to get to, stirring to watch from and paid for virtually nothing. Most comforting of all, a parka is no longer required attire.

Willie Mays, the greatest Giant of them all, never played at Oracle Park—but he might as well call it home. One visit to the main entrance and you’ll understand. Step off the crosswalks at Third and King Streets and you come upon an open plaza that is all things Say Hey. Addressed as 24 Willie Mays Plaza, the entrance includes a replica of Mays’ Hall of Fame plaque and a main ticket passage named Willie Mays Gate. But the centerpiece within this square is a nine-foot tall bronze sculpture surrounded by palm trees—yes, 24 of them—depicting Mays launching one of his 660 career home runs. At the sculpture’s base, former Giants owner Peter Magowan and his wife Debby have left an inscripted note: “Given in honor of Willie Mays and his fans, wherever they may be.”

Finding those fans, wherever they were, and getting them to come to the Giants’ previous home at Candlestick Park had become an exercise in utter futility. Bay Area fans loved the Giants, but they grew to hate Candlestick and its infamously Arctic, gusty microclimate. So they had to make a choice: Do they go to Candlestick and give their love to the Giants, or do they stay warm at home? Many chose to stay warm.

Compounding the Candlestick conundrum was the 1971-72 expansion to accommodate the NFL’s 49ers, which turned the ballpark into a enclosed, multi-purpose stadium with artifical turf as hard as Alcatraz rock. Giants owner Bob Lurie, who bought the team from Horace Stoneham and saved it from a move to Toronto in 1976, had to find himself an alternative not only for his sake but for the sake of his players and fans. And so he tried. Over and over again. One vote to build a downtown ballpark was squashed by the voters in 1987. A similar iniative two years later, piggybacking off the specter of a Bay Area World Series between the Giants and the Oakland A’s, appeared headed for a slim victory—but then the Loma Prieta earthquake hit. San Francisco voters, reprioritizing amid the dotted ruins, downed the measure by a single percentage point.

After two more ballpark votes failed down the freeway in San Jose, Lurie—a known nice guy—ran out of pateince. Not only did he play the St. Petersburg card, he cashed it in—agreeing to sell the Giants to a group of investors who would move the team to Florida for the 1993 season.

Of the many scupltures encircling Oracle Park, the most prominent (and rightfully so) is that of Hall-of-Fame legend Willie Mays in front of the main gate. The shrine is surrounded by 24 palm trees to match Mays’ uniform number. (Chris Ayers)

Once more, a savior came forth. Peter Magowan, a food store magnate, had grown up in New York as a Giants fan—and by fortuitous coincidence moved with his parents to San Francisco the same year the Giants left the Polo Grounds. He was not about to follow them again to St. Petersburg. So he assembled a mass collection of investors and purchased the team from Lurie, assisted by then-interim commissioner Bud Selig—who with the other Lords of Baseball accepted Magowan’s comparitively low bid over St. Petersburg’s because it was in “the best interests of baseball” to keep the Giants in San Francisco.

Escape From Candlestick.

Like Lurie before him, Magowan had no sympathy for Candlestick Park and worked on securing a new downtown ballpark. Unlike Lurie, he didn’t air threats to leave. Instead, he wisely displayed a kinder, gentler tone in building support to put a new iniative on the ballot. On top of this, Magowan cast into the electoral waters some very tempting bait: The Giants would pay for the whole ballpark themselves. Not since Dodger Stadium was built in Los Angeles, 40 years earlier, had anyone done that.

Whereas in most other cities such a proposal would be an effortless slam dunk at the polls, Magowan and the Giants knew they would have to vigorously convince a city populace so intensely activist and diverse in character, they would “vote no in their sleep,” as local sports columnist Ray Ratto once joked.

The Giants skillfully went to all corners of the political spectrum and gathered an impressive array of support. Included on this bandwagon were politicians from the right, left, and far left; activists for the homeless, the environment and the gay community; and swashbuckling, newly-elected San Francisco mayor Willie Brown, who as California State Assembly Speaker in 1992 ridiculed Magowan’s attempt to save the Giants by stating that San Francisco was “not a baseball town—never was, never will be.” To run its campaign, the Giants snagged the campaign manager who had manned the attack against the ballpark initiatives of the late 1980s.

Providing no match for the Giants’ firepower were grass roots opposition forces who complained that a ballpark at China Basin would increase traffic, noise, and cause sewer backups. They also tossed exaggerations that the ballpark, despite the Giants’ intentions of private financing, might actually cost the public up to $100 million.

In March 1996, the voting public took Magowan’s promise to heart and approved the measure by a 2-to-1 rate. After 40 years, San Francisco and its Giants were about to take a quantum leap from one of the country’s most maligned sports facilities to one of its very best.

The Giants’ next challenge, most everyone thought, would be even more formidable: Coming up with the $300 million to build the ballpark. Economists prophesized that Magowan would get competitively handcuffed with an annual debt service bill of up to $20 million. Fellow team owners also publicly frowned on the Giants’ effort, not because they didn’t think it would work, but because they were scared that it actually would—possibly leaving their cities with something to point to if the time came for teams to demand a publicly subsidized ballpark.

Potential sponsors for the new facility lined up at the Giants’ executive offices like golddiggers flocking toward a loaded vein. Pacific Bell paid $50 million to have the ballpark bear its name; millions more were anted up for prominent advertising within the ballpark. That was predicted; what surprised the naysayers was how eager bank lenders were to set up a financing deal. In the end, the Giants said no to over 10 competing major banks and said yes to Chase Manhattan, which put up $170 million to get Pac Bell Park—the ballpark’s original name—rolling.

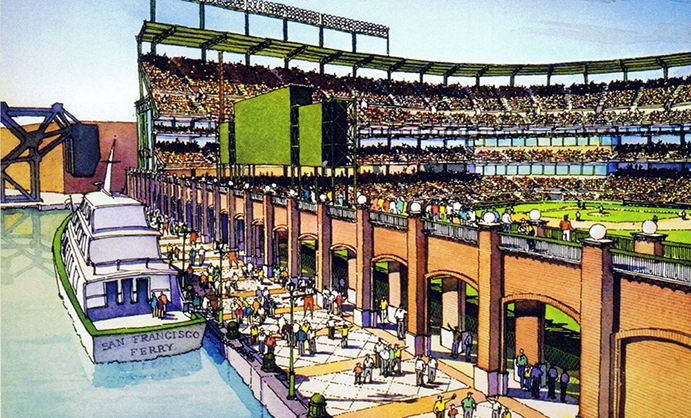

One of HOK Sport’s early sketches of Oracle Park shows the main scoreboard being planted atop the right field arcade. That idea was nixed due to support and visibility concerns.

A Beautiful Reflection.

HOK Sport’s Joe Spear, the architectural mastermind behind Oriole Park at Camden Yards, Jacobs Field and Coors Field, found in Oracle Park a salivating challenge to create something dramatic to rival the plethora of San Francisco landmarks, and to appease the architectural savvy of city residents. “(The Giants) wanted something that fit the neighborhood and fit San Francisco,” Spear told the Santa Rosa Press Democrat. “It was clear baseball was important. They wanted something that said baseball.”

Spear sought to design something that would blend in perfectly with the various surroundings. The tall brick façade was an intentional bow to the nearby warehouse districts. The open, charcoal-colored steel supports matched perfectly with the adjacent Third Street Bridge, later to be renamed after favorite San Francisco baseball son Lefty O’Doul, and for which would courier the bulk of Oracle Park fans from its parking lots. And for the outer façade of the right-field portwalk that borders McCovey Cove, Spear was talked out of using brick when a Bay Area-bred colleague suggested a concrete wall lit in lighter hues to “create a beautiful reflection on the water” as did many pier buildings along the bay.

Oracle Park was initially orientated so that most fans looked straight out at downtown San Francisco and the Bay Bridge. But a very important consideration doomed this panoramic tableau: The wind. Though not as intense or icy as those encircling Candlestick Park, the wind was influential enough to convince the Giants that they had to shelter their fans in the best way possible, even if it meant turning its back on downtown. The final decision to rotate the ballpark 90 degrees clockwise came after the team hired an engineering expert from the University of California at Davis, who took a model of the ballpark and literally placed it in a wind tunnel to see what position worked best.

Redirected, Oracle Park hardly cheats its spectators out of any breathtaking vistas. The Bay Bridge is still visible from the first base side, and most everyone gets an eyeful of the San Francisco Bay and beyond to downtown Oakland and the East Bay hills. The higher you sit, the better the view. And while some associate the upper deck at ballparks with cheap tickets, nose bleeds and Bob Uecker, the Giants performed a stroke of marketing genius and labeled the upper reaches of Oracle Park the “View Level.”

Though they’re far from the closest seats to the action, the upper “View” level at Oracle Park blesses fans not only with sights of the Bay Bridge and Treasure Island, but also an uninterupted view of a splash hit into McCovey Cove.

Going, Going, Wet.

Beyond the bay, the upper-deck fans along the right-field line also get an uninterrupted view of the most exciting baseball moment Oracle Park has to offer: The splash hit.

When the first ballpark renderings were made public, all eyes made a tantilizing beeline to right field. The thought of a long fly ball landing in the bay became the talk of the town. Years after the ballpark’s opening, the topic still resonates with energy.

McCovey Cove, the parcel of water behind Oracle Park, was coined by San Jose Mercury News sportswriter Mark Purdy and named in honor of Willie McCovey, San Francisco’s first left-handed Hall-of-Fame slugger. But in the ballpark’s first seven years, it was totally owned by the man who very well could be the second: Barry Bonds. Baseball’s prime lighting rod of the steroid era teed off on the cove in January 2000 as glove-toting construction workers watched the ballpark’s first majestic arcs sail high over their heads and into the water. When the pitches began to count, Bonds became the first player to hit it into the cove during the Giants’ ninth game at Pac Bell Park; in fact, he was responsible for the first four splash hits, and the first nine by a Giant. By the time he splashed for the 35th and last time in 2007, only seven other Giants had combined to drop 10 bombs into the cove—while 10 opposing players had gone wet 14 times. Take Bonds out of the equation, and the average number of splash hits per year at Oracle has averaged roughly four a year. That figure drops to a flat zero for right-handed bats; no player has ever hit an opposite-field shot into McCovey Cove.

The fun doesn’t end once the ball hits the water. Sea vessels from kayaks to yachts float about in McCovey Cove and await the inevitable splash hit. When the ball comes dunking in, the boaters often react just as recklessly as the bleacher bums behind the outfield wall; it certainly raised the eyebrows of viewers who witnessed a couple of boats colliding off one another trying to scoop up Bonds’ first-ever splash hit. And when Bonds was due for one of his many milestone homers at Oracle Park—there was his 500th carrer home run, and his 600th, and 700th, and 756th and, oh yes, his 70th and beyond for the season in 2001—the cove often filled up with so many manned floating objects that it was possible for a fan to jump down from the portwalk and tip-toe his way across the cove without getting his feet wet.

When Barry Bonds was at the plate, McCovey Cove became a crowded place to navigate. (Flickr—Josh Friedman)

For all the excitement that the splash hit brings, the architecture between the outfield and the water proves just as engaging. From the right-field pole, a 25-foot-high brick wall—raised high in part to prevent cheap home runs—juts out 110 feet to right center and is adorned with five arched openings, outlined in white and influenced by the walls at Groton School in New York where a young Peter Magowan was once educated. The wall then makes a brief diagonal intrusion into right field, then turns back on its original course until it slices into the center-field bleachers and fades to its end. Given this tight, disproportional real estate, it seems almost bizarre that Major League Baseball initially insisted to the Giants that Oracle Park carry symmetrical field dimensions and consistent fence heights.

Arcade Games.

There’s a whole lot going on behind, atop and even within the right-field wall or “arcade.” Just three rows of seats line the top of the wall nearest to the right-field pole, and they’re some of the most cherished in the house. Behind these bleachers, the concourse is a major temptation for fans to vacate their seats and stroll slowly through—and they often used to stop and wait when Bonds came to the plate. A lot of them were waiting on October 7, 2001, when he launched his record 73rd and final shot of the season into a mass of spectators so densely packed, they began to understand how sardines felt. One man came away with the historic souvenir, but another sued—claiming he had it first. The two went to court, settled and agreed to auction off the ball and share the profits—but even after it was sold, they each finished in the red thanks to a stack of legal bills. Greed, in this instance, was not good.

For each of the five main archways behind right field, the doors are open for folks on the outside to walk up behind the screen fencing and watch the game for free. There is a catch: You’re only allowed to watch for three innings. (Chris Ayers)

With all the attention directed toward right field, the Giants have worked hard to compensate behind the left-field bleachers, itself behind more mainstream field dimensions and fence heights. A “fan lot” area behind the bleachers includes a giant, neon-lit skeletal structure of a Coke bottle, titled at an angle and housing a small network of slides for the kids; a mini-Oracle Park, complete with a mini-Jumbotron screen and aquarium embedded in the outfield wall, for little ones to run the bases; and a massive steel-and-fiberglass replica of a 1927 baseball glove, wrinkles and all, measuring 26 feet tall by 33 feet wide. The glove is positioned in a way that shouts “hit me!”, although at 501 feet from home plate, it’s a bit tough to get there. One player did: Vladimir Guerrero, during the 2007 Home Run Derby. Otherwise, the batters would rather take their chances reaching McCovey Cove.

The few controversies to take place during construction were mostly trivial, in part because the ballpark’s private financing reduced the odds of bureaucracy nosing in. There were some political fights to deal with, such as securing a waver on a lengthy environmental review, and what to do with lead-tainted dirt dug up at the site. Early fears of glare and noise spilling into the surrounding neighborhood were dispelled when the Giants customized their lighting and sound systems to reduce outside disturbances. And some community activists carped about the giant Coke bottle as seen from the outside and its perceived overt commercialism, but their threat to sue for its removal was an empty one.

A tally of the number of Giants home runs hit into McCovey Cove is kept in scoreboard-like fashion next to the right-field foul pole. Barry Bonds is responsible for the majority of the number listed. (Flickr—Randy Chiu)

The corporate advertising inside Oracle Park is much more omnipresent, but the Giants needed to pay their full share of the lease somehow. Still, some of the ad space is cleverly incorprated. The right-field arcade is named Old Navy Landing and features a “Splash Hit Counter”—only Giants players need apply—and four naked pillars that shoot plumes of heavy mist straight into the air whenever a Giant belts one over the fence. Over in left field, the outfield wall contains a lengthy ad for long-time Giants sponsor Chevron with its signature animated cars bubbling up over the top of the wall; it led to one of the greatest radio calls in Giants history when famed broadcaster Jon Miller, in describing a game-winning double by Jeff Kent in 2000, exclaimed on air: “It’s off the top of the wall! It’s off the top of the cars!” Initially, the headlights (or eyes) on the cars actually came to life with light and eye movement, but it became too distracting for players and fans and the Giants had the display tempered.

Other sponsorships didn’t fare so well. In the ballpark’s first year, Old Navy created Rusty the Mechanical Man, a sizeable robot that emerged from a shed near the right-field pole and mimicked baseball moves. Reactions varied from “stupid” to “vaguely creepy” to, well, no reaction at all; Rusty was quietly and hastily removed early in his first year, never to return. A bigger headache came later when Webvan, an online grocery home delivery service, went from boom to bust in the dot-com industry’s first wave—leaving the Giants trying to figure out how to remove the company’s name from every cupholder in the ballpark. And then there was the ballpark name itself; Pac Bell Park to start, then briefly SBC Park when it finished its seven-year absorption of Pac Bell, and then AT&T in 2006 when the telecommunications giant merged with SBC. Starting in 2019, local software leader Oracle paid handsomely to replace AT&T on the building’s facades.

Not as Small as You Think.

When the finishing touches were applied to the ballpark in 2000, everyone knew it was going to be a beautiful place. The question was: How was it going to play between the lines? The minimal foul territories and short, 309-foot distance down the right-field line left many to believe that Oracle Park would not be kind to pitchers. At first, it appeared their intuitions would prove them right. Six homers were hit in the first game, an exhibition against the New York Yankees. Six more were driven out in the inaugural regular season game, including three alone by Kevin Elster of the visiting Los Angeles Dodgers. Oh boy, everyone gasped: Bandbox.

Fears of the Giants’ new yard becoming Coors Field West would quickly be alieviated, as pitchers discovered some nice wide open spaces that played into their hands. Yes, 309 feet is a short trip to the right-field foul pole—but 404 to the left of center isn’t, and certainly neither is the very distant 420 feet to the right-center gap which, with the 25-foot wall behind, is a place where home runs go to die and triples thrive. Once the Giants’ pitching staff caught on and started getting opposing hitters to give it their best shot toward the gaps—often leading to long outs—Oracle Park cemented its status as a pure pitcher’s park. And after Kevin Elster’s three homers on Opening Day 2000, no one—not even Barry Bonds—would net a hat trick again at the yard until Pablo Sandoval boomed three over the wall in Game One of the 2012 World Series.

The brick-laden right-field wall, one of the majors’ most difficult for outfielders to adjust to, starts at the foul pole a mere 309 feet from home plate—but juts out to 415 feet in “Triples Alley” as it meets up with the center-field wall.

For anyone playing Oracle’s right field for the first time, a baptism by fire is sure to ensue. Few if any outfielding assignments are tougher in the majors. Because one has so much area to cover in right-center, right fielders are typically stationed further away from the right-field line. Between the shots toward the “Triples Alley” gap in right-center and the drives pulled down the line, there’s going to be a whole lotta runnin’ goin’ on. It gets worse; the line drives caroming off the arcade wall could go in any one of a million directions, depending on whether it hits off the brick, the padding, the meshed archway fencing or the sides of the archways themselves. It’s not uncommon for the poor right fielder to be hopelessly chasing a ball to 415, the right-field line or back to the infield.

Oracle Park’s reputation as a pitcher’s park has been affirmed by the numbers. The ballpark frequently ranks around the middle in terms of batting average but decidedly in the lower third for scoring and home runs. Such factoids have scared many a free agent slugger from considering the Giants as their next employer. In 2010, Adam LaRoche spurned a nice offer from San Francisco for a much smaller deal in Arizona and slugger-friendly Chase Field. LaRoche got his stats but didn’t get a ring; the Diamondbacks lost 97 games while the Giants won their first championship in 56 years.

Empty Seats? Where?

The Giants’ fans were bound to embrace Oracle Park from the start—after tolerating Candlestick for 40 years, a common little league park would have done so long as it wasn’t accompanied by frigid, gusty winds—but their enthusiastic reaction to the ballpark has exceeded the Giants’ wildest dreams. Three million tickets were sold before the first pitch in 2000, and the three million barrier has been consistently upheld ever since, slipping below the mark in 2008-09 during the blasé lull between Bonds and three World Series titles.

Even Gary Radnich was impressed. The veteran Bay Area TV and radio sports personality, never afraid to play the devil’s advocate, figured the Giants could fill up the park on weekends and whenever the Dodgers came to town. But the true test, he suggested, would come when a major league straggler like Montreal showed up for a midweek series. So when the Expos came to town on a Monday, the Giants drew 40,000; they did it again on Tuesday, and once more on Wednesday. The thought was to hold Gary Radnich Night for one of the games, but he graciously declined. He would have been the only no-show in an otherwise full ballpark.

Looking out toward right field from the upper deck, with excellent views of the shipping piers and beyond as the San Francisco Bay stretches south toward San Jose—once a rumored home for the Giants before Oracle Park was approved. (Flickr—Mr. Littlehand)

If Oracle Park’s aesthetics and functionality aren’t enough to win fans over, then the ease of getting there will, even with sellout conditions for every game. Everyone drove to Candletsick; they had no choice, given the very limited mass transit options. It’s a far different story at Oracle Park. There’s a Muni light rail stop that drops off thousands of Giants fans right at the doorstep to the ballpark’s main entry; a few blocks down King Street, thousands more hop off at the end of the line from CalTrain, servicing the hotbeds of Giants fandom down the peninsula and southward to San Jose. And for those coming from across the bay, there’s a ferry dock behind the center field entrance while BART has stops for those who don’t mind taking the roughly nine-block walk from the heart of downtown.

Once at the ballpark, fans have a myriad of eating options to choose from. Adjacent to the Willie Mays gate is a full-service restaurant originally called 24, then ACME Chophouse, and now The Public House, boasting upscale food at competitive prices. Inside the gates, fans can grab a hotdog at numerous Doggie Diners, a long-time San Francisco staple, and they’ve always been all over the irrestible garlic fries whose aromatic echoes drift from nearby Steinbeck country south of the Bay Area. Edaname is not the first thing you’d think of for ballpark food, but Oracle Park’s got that, too. And in 2014, the Giants made use of the vacant area behind the center-field wall and opened up The Garden, a verdant health-food alternative spot adorned with planters full of vegetables and fruits—which, when harvested, are used for menu items.

The Giants initially promised that Oracle Park would be used for little other than their own games, but over the years they seemed to have drifted away from the idea. There have been numerous concerts, college football games, rugby matches and World Baseball Classic contests; Cirque de Solail has staged shows, American Idol has held auditions and, in perhaps the unlikeliest use of Oracle Park rental yet, hip-hop artist Kayne West set up a full orchestra on the field, brought in reality TV starlet Kim Kardashian and proposed to her.

Nobody in the neighborhood seems to mind Oracle Park and its influence anymore. The 50% of residents who at first grumbled over the idea of a ballpark seem to have come around—or maybe they just moved away. Oracle has become a beacon for waves of aggressive residential and business growth, turning a once neglected district into a chic place to reside, work, congregate—and, oh yes, take in a ballgame.

Years after the Giants threatened to leave town without their own private China Basin, there’s no doubt that the team is here to stay. But should the Giants become a memory, so would the ballpark. Literally. It’s in the lease: If the team leaves after 2022, it’s stipulated that Oracle Park must be torn down by the city and returned to its “original condition.” Among the many questions should that happen is this one: Who pays to bring back all the lead-tainted dirt?

But don’t count on this ballpark being thrown into the hands of demolition experts anytime soon. Oracle Park has rightly taken its place alongside Fenway Park and Wrigley Field as among the greatest of all ballparks, a shrine to the Giants of the past and present—not a mallpark, but a pure, no-frills baseball facility with so much spectacle to offer on the field and in the waters beyond.

The Ballparks: Candlestick Park Mark Twain said that the coldest winter he ever spent was summer in San Francisco. It’s quite possible that he spent it at Candlestick Point, which years later would beget Candlestick Park—a windswept tundra where fans and players alike held on to their hats, parkas and hot chocolate as they struggled to enjoy the summer game in Arctic-like conditions and exclaimed “vinim, vidi, vixi” before thawing out.

The Ballparks: Candlestick Park Mark Twain said that the coldest winter he ever spent was summer in San Francisco. It’s quite possible that he spent it at Candlestick Point, which years later would beget Candlestick Park—a windswept tundra where fans and players alike held on to their hats, parkas and hot chocolate as they struggled to enjoy the summer game in Arctic-like conditions and exclaimed “vinim, vidi, vixi” before thawing out.

The Ballparks: The Polo Grounds Peculiar doesn’t even begin to describe the Polo Grounds, a bathtub of a ballpark that yielded pop fly home runs and tape-measure outs as it led almost as many lives as a cat against the rocky bluffs of Harlem. Through its resiliency, it manifested more than its share of baseball’s legendary moments and unforgettable actors, whether it was McGraw, Mathewson, Merkle, Master Melvin, Mays or, yes, even Marvelous Marv.

The Ballparks: The Polo Grounds Peculiar doesn’t even begin to describe the Polo Grounds, a bathtub of a ballpark that yielded pop fly home runs and tape-measure outs as it led almost as many lives as a cat against the rocky bluffs of Harlem. Through its resiliency, it manifested more than its share of baseball’s legendary moments and unforgettable actors, whether it was McGraw, Mathewson, Merkle, Master Melvin, Mays or, yes, even Marvelous Marv.

San Francisco Giants Team History A decade-by-decade history of the Giants, the ballparks they’ve played in, and the four people who are on the franchise’s Mount Rushmore.