THE BALLPARKS

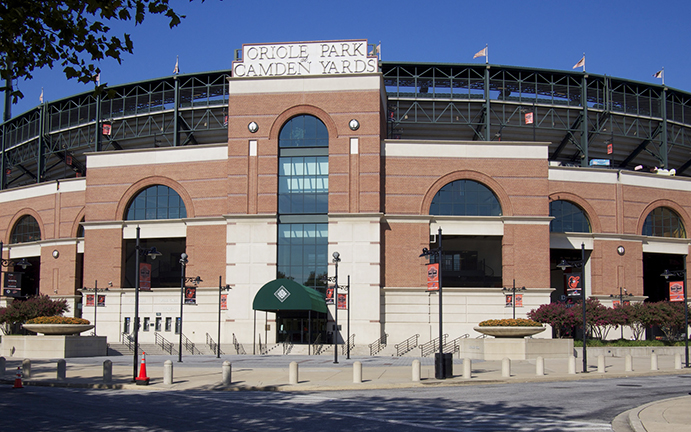

Oriole Park at Camden Yards

Baltimore, Maryland

(Carol M. Highsmith’s America, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division)

To say that nostalgia was at the forefront of those behind Oriole Park at Camden Yards is the understatement of yesteryear. The Baltimore Orioles went back to the city, to the very spot where Babe Ruth’s father used to serve drinks, and built a baseball fortress unlike anything seen since Ebbets Field met the wrecking ball. They even rethought the overlong and ancient B&O Warehouse behind right field, embracing rather than destroying it—thus transforming urban blight into trendy atmospherics.

Habit. It’s a distinctive American trait that usually follows on the coattails of that other great American trait, ingenuity. Someone’s brilliant, original idea becomes the blueprint for others to jump on and imitate, resulting in the trend, the fad, the craze. A yogurt stand opens somewhere and a million other people follow suit. A poker game is shown on TV one night, and before you know it, every basic cable outfit is doing the same. Zombies are everywhere.

In Baltimore, the government entity put in charge of building a new venue for the Orioles instinctively followed habit and originally considered a sterile, concrete multi-purpose behemoth because, why not—that’s the way stadium architecture had been for 30 years. Fortunately, there were enough creative people orbiting the project ready to take a left turn from convention with a different, more genuine vision. People like the hard-nosed Orioles’ front office man who grew up in the shadows of Pittsburgh’s Forbes Field and longed for a return to an intimate baseball setting. Or the veteran sports architect in Kansas City looking to break away from the same old same old so often dictated to him by habit-driven clients. Or the energetic, determined young woman who crashed onto the scene with a remarkable eye for aesthetic civic harmony. Or the student architect in upstate New York who may have been the only one to look at the venue’s elderly surroundings—most notably the one-fifth mile-long B&O Warehouse that’s become the ballpark’s signature element—and suggest that it all be kept rather than torn down.

Oriole Park at Camden Yards would be their creation. Nearly three decades after its opening, it’s looked upon by some as just another ballpark—but that’s because many other major league teams have taken its template and copied it to one degree or another. There it is again: Habit from ingenuity.

What shouldn’t be lost on the Millennials who today frequent Oriole Park is that when it opened in 1992, it took the baseball world—if not the world in general—by storm. Its cozy antiquity, rustic environment and pure allegiance to baseball was unlike anything seen in sports, a welcome antithesis to the generic, municipally-driven concrete bowls of recent times. The ingenuity of Oriole Park is that it made ‘old’ new again, at a time when people yearned for a simpler past free of modern stress and overbearing technology.

Bud Selig, whose immensely profitable tenure as baseball’s commissioner coincided with Oriole Park’s first 25 years of operation, likely wasn’t reaching for his usual promotional hubris when speaking about the ballpark’s influence. “Camden Yards may be one of the two or three most powerful events in baseball history,” he said. “It changed everything. It really did. I’m not sure people grasp the significance of it.” The Orioles agree. They call Oriole Park “The Ballpark That Forever Changed Baseball,” a statement they are so convincing and proud of that they’ve trademarked it.

Pregame activity outside the Eutaw Street gate, with a statue of Baltimore native Babe Ruth in the foreground at right. (Bigstock)

Saving Baltimore.

The Oriole Park story begins in the mid-1980s, when pro sports were becoming an endangered species in Baltimore. Basketball’s Bullets had long since mosied down the beltway to Landover, located on the outskirts of nearby Washington, but the dagger that hit Baltimore’s heart with all the precision of an Abraham Van Helsing strike was the midnight move in the winter of 1984 of the NFL’s Colts, a beloved team fallen on recent hard times, to Indianapolis. That left the Orioles as the only game in town—but some wondered how long they’d last, given that they had been recently been purchased by high-powered Washington lawyer Edward Bennett Williams. Whispers were constant that Williams might relocate the Orioles 40 miles south to his D.C. base.

Memorial Stadium, a noble yet graying relic spaciously situated in the middle of a working-class neighborhood in the city’s northeast quadrant—miles from the nearest freeway—had served as the Orioles’ home for nearly 40 years. There was nothing romantic about the place, except for the memories of some great baseball played by the home team over the years. But Memorial didn’t contribute to that greatness; it was a bland witness where a loyal fan base came not for it, but for the Orioles. It wasn’t getting any younger, nor was it aging with nostalgic grace a la Wrigley Field or Fenway Park.

There had been talk of a new ballpark or shared stadium with the Colts as far back as 1967, when local architect Bo MacEwen was asked to sketch out a facility that was decades ahead of its time—a multi-purpose stadium with a retractable roof, video board and an adjoining commercial/retail complex, all dressed in a bulky exterior that seemed to be made from oversized wooden toy blocks. The concept was so unusual that Baltimoreans didn’t know how to react, so they didn’t—as they wouldn’t for other, more common stadium/ballpark concepts that popped up every five years or so, all of them to be located at Camden Yards.

The Colts’ departure, however, intensified the urgency to build something for the Orioles while luring a NFL team back to Baltimore. Leading the charge from the political end of the spectrum was enigmatic Baltimore mayor William Donald Schaefer, who’d been trying for much of his long tenure to get something built downtown for the Orioles. As luck would have it, Schaefer became the governor of Maryland in 1987—just six months after the creation of the Maryland Stadium Authority, whose job it was to lend financial aid for sports facilities throughout the state. The money would not be pulled from tax revenue but from a state lottery, a voluntary tax of sorts played mostly by lower-income residents hoping to get rich quick. Of course, few would.

Sensing a tough battle with the two state senate subcommittees that would vote on the stadium project, Governor Schaefer brought in Edward Bennett Williams himself to lobby the politicians. Frail and dying of cancer, the Orioles owner took to the floor and, using his esteemed law experience, gave the summation of his life with an impassioned yet humble tone, insisting that he wasn’t looking for a subsidy and declaring at the end that “I’m here forever.” The jury was swayed; the two subcommittees voted for the funds three weeks later by a combined 20-4 vote.

The anticipated pitchfork rebellion ensued, with a grass roots anti-stadium campaign—fueled by polls of Baltimore residents rejecting a publicly funded facility—taking their argument to the top of the legal ladder before the Maryland Court of Appeals, wielding the last word, struck it down.

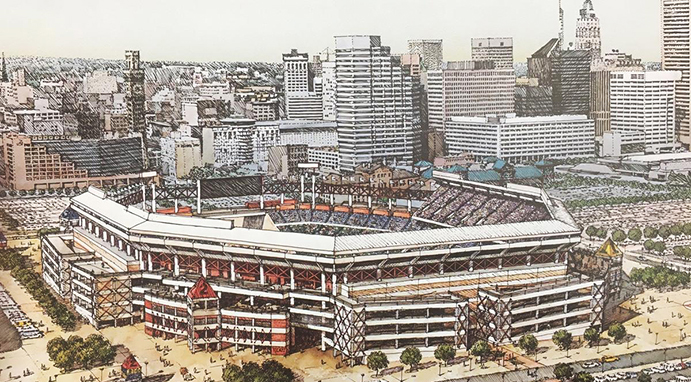

One of the early sketches for Oriole Park shows a more modern look with a myriad of pedestrian ramps and street-level parking, while the B&O Warehouse is gone. The Orioles didn’t like it.

Don’t Build Us a Yugo.

The evolution of What’s Next for the Orioles quickly went from Spartan to spectacular. The Maryland Stadium Authority’s first thought was to upgrade Memorial Stadium but was talked out of it, as it would fail to exude first-class character while the lousy traffic issues would remain. For building from scratch, many sites were considered—including the obligatory (and, yes, habitual) thought of building in the suburbs between Baltimore and Washington, where the Bullets, hockey’s Washington Capitols and (eventually) the NFL’s Washington Redskins would relocate. But the clear leader in the clubhouse was Camden Yards, a former rail/industrial site rotting just blocks to the west of Inner Harbor, the center of Baltimore’s tourism universe. It was agreed that building a venue there would spur redevelopment and expand the economic vitality of the downtown region.

A multi-purpose stadium concept was shot down when a cost analysis revealed that building two separate facilities—one for baseball, the other for football—would be only slightly higher in total expenditures. With the MSA okaying twin venues, the Orioles now knew they’d have a place all to themselves.

This was music to the ears of Larry Lucchino, the Orioles’ vice president and chief counsel. He grew up in Pittsburgh and admired the old-style quirks and asymmetry of Forbes Field before they put a wrecking ball to it. Forbes was for baseball only, and so would his team’s new ballpark; Lucchino was one of many who lobbied hard against the multi-tenant concept, correctly concluding that baseball’s most hallowed teams—the New York Yankees, the Boston Red Sox, the Chicago Cubs and Los Angeles Dodgers—all played in baseball-specific facilities while most everyone else was slogging it out at generic cookie-cutter stadiums.

HOK Sport, the venerable Kansas City sports architect firm hired on by MSA for Camden Yards, was at the time progressing along with Chicago’s New Comiskey Park, another baseball-only venue—but it wasn’t the type of ballpark Lucchino wanted. With its scenery-chewing pedestrian ramps, minimal ornamentation and steep, distant upper deck, New Comiskey lacked intimacy and old-fashioned resonance. When HOK’s first visions of Camden Yards looked to be borrowed from the New Comiskey blueprint, Lucchino—a man known for his irate temperament—got in their faces not with an angry rant, but with brochures for the miserly European compact car, the Yugo. His message was clear: Don’t make our new ballpark a Yugo.

Joe Spear, HOK’s lead architect, didn’t want a Yugo either. In fact, he probably had much in common with Lucchino’s point of view. A few years earlier, Spear had designed Pilot Field, a minor league ballpark in Buffalo with intricacies and appeal borrowed from Forbes, Wrigley and perhaps even Buffalo’s own War Memorial Stadium, where The Natural had been filmed. But the White Sox didn’t want to go in a retro direction for New Comiskey, and the MSA’s early budget restraints on Camden Yards handicapped Spear’s ability to get creative with the Orioles. But Lucchino soon took care of that. When the Orioles agreed with the MSA on a lease agreement for the new ballpark, he added in a clause giving the team power to approve all design-related decisions—thus giving it control over how it would look.

Eutaw Street remains vibrant before, after and during Orioles games for ticketholders. Note the light standard atop the B&O Warehouse to make it feel closer to the ballpark. (Wikimedia—Mr. Schultz)

The Warehouse.

As many old industrial structures were being brought down so Oriole Park could be built up, one remained standing: The B&O Warehouse, an old train facility which sat adjacent to the ballpark property. Completed in 1905, the warehouse was a curio for anyone laying their eyes on it for the first time; it rose eight stories, measured a mere 51 feet in width and ran a never-ending 1,016 feet in length—making it the longest building east of the Mississippi. But it was abandoned, an eyesore with “demolish me” written all over it. Oddly enough, that’s what Lucchino, the champion of the classic ballpark, wanted to do. So did most everyone at MSA. Initially, anyway.

Meanwhile, Adam Gross, a principal in the Baltimore architectural firm of Ayers Saint Gross—good friends of Lucchino who would eventually lose out to HOK on landing the Oriole Park gig—was invited to Syracuse University in New York to judge a presentation of projects from graduating students. One of them, Eric Moss, just happened to have a model of a new Orioles’ ballpark—with the B&O Warehouse not only surviving but being an integral part of the experience. Its long western facing doubled as part of the right field wall, while inside the warehouse there would be a restaurant where patrons could watch the game. Moss also included a tall tower with a soaring antenna that cut off the upper two decks down the right-field line as an ode to the radio days of old. Gross all but hired Moss on the spot, asking him to bring his model and plans down to Baltimore.

Shortly after Moss’ arrival at Ayers Saint Gross, the cat got out of the bag and the model became the talk of the town, with Moss suddenly finding himself making the rounds with local media to discuss his vision. Among Orioles fans, the thought to integrate the warehouse was a hit, creating a vibe in sync with a time when movies like Field of Dreams, The Natural, and Eight Men Out successfully stimulated people’s interest in the baseball of yesteryear. To Baltimoreans, the warehouse represented the inviting potential of living a charming, old-time urban experience.

Not surprisingly, Moss’ model created a sharp shift in momentum among those in charge; they now believed keeping the warehouse was a good idea, after all. Not only that—some began claiming that it was their idea, too. Perhaps that’s true, but beyond the initial 15 minutes of fame, Moss—who came off as the only one with self-assured conviction of his claim regarding the warehouse—never received any kind of official acknowledgement for it. Looking back, Moss couldn’t help but admit to author Peter Richmond, in his book Ballpark, that he felt “a little violated” from the experience. The consolation prize for Moss is that, nearly 30 years later, he’s still happily working for Ayers Saint Gross, designing mostly student facilities at universities.

The Orioles would improve upon Moss’ warehouse concept. Instead of attaching the ballpark to the warehouse, they would separate it by keeping Eutaw Street, creating an engaging environment that was part plaza, part walkway. On one side was the ballpark, mostly visible so fans could feel attached to the activity within; on the other was the rejuvenated warehouse, with restaurants, pubs and a team store. The MSA eventually convinced the Orioles that their team offices, originally sketched out to be located behind the home plate entrance, should be in the warehouse; the team reluctantly agreed, if for anything else, because it would save money.

Bringing the warehouse back from the dead was a project in itself. It took $20 million to fix up years of neglect, with nearly 1,000 windows replaced and goodness knows how many bricks literally hand-washed, one by one. HOK would provide a final masterstroke by installing a horizontal rack of game lights atop the warehouse to make it feel more integrated with the ballpark.

A Woman’s Touch.

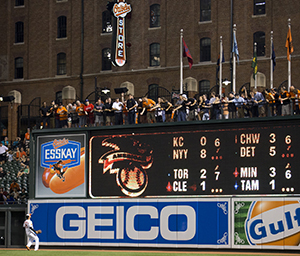

The elegant antiquity and exposed steel of the Oriole Park scoreboard is palpably representative of the ballpark’s old-fashioned feel. (Flickr—Keith Allison)

With everybody in place—to say nothing of in sync—Oriole Park began rising from the flattened dirt and gradually began to reveal the old-style touches that would make it most unique for the time. A façade featuring arches and brick. The exposed steel. The wrought iron fencing. The asymmetrical outfield. Irregular wall heights. Tiered bullpens. Dark green seats, designed and shaped to look wooden and were tantalizingly close to the action. The flat upper-deck roof, enhancing intimacy. No major stadium built partially or wholly for baseball had, for generations, even considered any of these elements.

The project in process received high praise from no less than the New York Times and its architecture critic Paul Goldberger, who two full years before Oriole Park’s completion wrote that the ballpark was “capable of wiping out in a single gesture 50 years of wretched stadium design, and of restoring the joyous possibility that a ball park might actually enhance the experience of watching the game of baseball.” But others just didn’t get it, like Baltimore Sun columnist John Steadman, who wrote: “Baltimore is the only city in America that’s actually trying to create an old stadium. If it’s being built to look old and rundown, we already have one of those.”

As Oriole Park’s debut approached, a few last-minute headaches had to be treated. Some of the seats didn’t face toward the infield as they were supposed to. At least those fans could see the whole field; the same could not be said for some unlucky ticket purchasers of aisle seats in the right field bleachers, whose view would be so obstructed by the flat, elevated entry area adjacent that they wouldn’t be able to see first base. When the Orioles also discovered that the dugouts would provide a visual obstacle for front-row patrons, they had to lower them. Then there was the soap opera over the name of the ballpark. Governor Schaefer wanted it to be Camden Yards. Eli Jacobs, the new Lord of the Orioles following the passing of Edward Bennett Williams, replied with equal insistence that it be Oriole Park. The two agreed to fuse both thoughts together—but Schaefer fumed when the first signs to be hoisted up on the B&O Warehouse displayed “Oriole Park” in a much larger type. He told Jacobs to fix it, immediately.

Oriole Park’s dignified home plate entrance is almost an afterthought as few people use it; the majority of fans arrive at the ballpark via Eutaw Street. (Flickr—Austin Kirk)

Love at First Site.

Oriole Park at Camden Yards officially opened for business on April 6, 1992 with a paid crowd of 44,568, but it seemed as if the whole world was present. The major TV networks set up camp to do their morning shows from the ballpark; President George H. Bush threw out the first pitch. Ironically, a place that would quickly secure a reputation as a hitter’s favorite was christened with a pitcher’s duel, as the Orioles’ Rick Sutcliffe threw a five-hit shutout over Charles Nagy and the Cleveland Indians in a spiffy two hours and two minutes.

Sutcliffe’s gem was basically a side attraction. The clear star of the day, the main event, was Oriole Park itself. Fans walked about the new ballpark, almost oblivious to the action on the field; activity was especially vibrant beyond the bleachers in the Eutaw Street plaza, where folks absorbed the warehouse experience and were treated to the first slabs of barbecue served up by popular ex-Oriole Boog Powell, inaugurating a concession tradition that continues to the present day. Oriole Park does have a formal home plate entrance that stands tall and classy with a touch of colonial splendor, but few use it; there’s relatively little parking near it, and it’s essentially choked off from the neighborhood by the adjacent, pedestrian-unfriendly Baltimore-Washington Parkway. The Eutaw Street plaza, Oriole Park’s back porch, is where it’s at for most fans entering the ballpark by car, by rail (local light rail and regional commuter trains have drop-offs on the other side of the warehouse) or by foot, some three blocks from historic Inner Harbor where Francis Scott Key wrote The Star-Spangled Banner during the War of 1812.

Oriole Park exceeded all first-year expectations. The Orioles would have been happy reaching three million in attendance; they got 3.56 million instead, selling out all but a few games. The players responded to the joint and the capacity crowds within, winning 10 of their first 11 games at home and finishing the year with an 89-73 record—a 22-game improvement over their final campaign at Memorial Stadium, the biggest such leap since the franchise moved to Baltimore 38 years earlier. The bottom line also proved positive; after barely breaking even in their final years at Memorial, the Orioles made a $28 million profit in 1992.

Critics raved over Oriole Park. Time named it one of the 10 best designs of the year. Baseball writer Bob Nightengale called it “state-of-the-art with the look of a master painting.” Fred Blinebury of the Houston Chronicle referred to it as “the Wrigley Field of the 21st Century.”

But not everyone was happy. Leading the charge, of course, was John Steadman, who defiantly remained negative even as everyone else was heaping high praise. “The warehouse offers absolutely nothing, and it destroys the vista of downtown Baltimore,” he ranted. “And if you buy the best seat in the house, next to the Baltimore dugout, you’re going to spend nine innings staring out a brick wall that reminds me of the Maryland state penitentiary.”

Others lamented over the changing demographic that Oriole Park would attract. “A lot of them weren’t watching the game,” wrote Rob Biertempfel of the Pittsburgh Tribune-Review. “More than one person was reading a paperback. Cellular phones were beeping. I saw one guy whacking away at his laptop computer, and I don’t think he was a sportswriter.” And then there was Herbert Muschamp, who may have shared the same New York Times office space as colleague Paul Goldberger—who earlier championed Oriole Park’s nod to the past—but not the same opinion. “To design these new buildings in a retro style,” Muschamp complained, “risks sending a message that contradicts their forward-looking purpose: that cities have no future except as well-endowed museums of their better days.”

There was even a bit of controversy among the accolades in terms of who was receiving them—and who wasn’t. A New York Times article credited Janet Marie Smith as Oriole Park’s architect while barely mentioning HOK, enraging the firm that did the bulk of the creative. Similarly infuriated were members of the MSA, who unfairly felt they were being typecast as left-brained bureaucrats when they contributed to and supported the design process.

In the years to follow, cooler heads and graciousness would prevail. Joe Spear, in Thom Loverro’s Home of the Game: The Story of Camden Yards, acknowledged, “There was a lot of heated debate about what the design should be or what the place should feel like or look like or be. But I think in the end everyone was trying to make it as good as it could be.” Smith herself would later give highest credit to Governor Schaefer and her boss, Larry Lucchino.

Among the many innovations put into use at Oriole Park are double-tiered bullpens, optimizing sightlines for relievers lying in wait while maximizing spectator seating options. (Flickr—Doug Kerr)

Feeling O’s So Good.

The 1990s would represent high times for the Orioles and their new ballpark. They posted winning records in five of their first six years at Oriole Park and made the playoffs in consecutive seasons (1997-98). The fans wouldn’t stop coming; the Orioles led the AL in attendance four straight years (1995-98), setting a franchise high in 1997 with 3,711,132 clicks of the turnstiles. Not even the ruinous 1994-95 players’ strike, which sank attendance most everywhere else in the majors, could sap the gates at Camden Yards, as the presence of the highly popular ballpark managed to remain above the misery of labor war fought between players and management.

Oriole Park fittingly became the setting for one of baseball’s few inspiring moments in the aftermath of the strike when, on September 6, 1995, Hall-of-Fame shortstop Cal Ripken Jr. accomplished what was previously considered impossible and broke Lou Gehrig’s hallowed record for the most consecutive games played. As the contest became official halfway through the fifth, the crowd exploded into cheers for the game’s new iron man, the multi-banner game counter on the warehouse wall was updated to “2,131,” and Ripken thanked the fans not only with a curtain call but with a lap around the Oriole Park field, slapping the hands of fans eager to congratulate him.

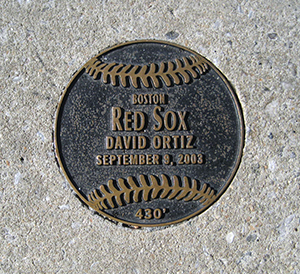

Eutaw Street is dotted with markers signifying the spots where home run balls have landed on the fly at Oriole Park. (Flickr—Kristin)

In more competitive, regular season play, there have been a multitude of home runs landing on Eutaw Street, short of the warehouse wall. On average, about four long flies will land there per year; in 2013, 11 such shots reached the plaza. Rafael Palmeiro, before he pointed his finger at politicians challenging his cleanliness, became the only player to do it twice in a game. Through 2015, Chris Davis has the most for a career, with eight. Walk down Eutaw Street and you’ll see markers where all the homers have landed—but if you want a quicker overview, the Orioles’ web site has a pretty cool interactive page devoted to the topic.

This isn’t to say that pitchers didn’t occasionally have their day at Oriole Park. Mike Mussina had many of them. The Baltimore ace, far and away the ballpark’s all-time leader in wins, tamed the not-so-distant fences and posted a 72-39 record and 3.58 ERA in 143 Camden Yards starts for the Orioles; on May 30, 1997, he came within two outs of a perfect game, conceding a single to Cleveland’s Sandy Alomar. To date, there’s only been one no-hitter thrown at Oriole Park, courtesy of Hideo Nomo—who has a thing for throwing no-hitters in offensive-minded ballparks (he’s also the only one with a no-no at mile-high Coors Field in Denver.)

Baltimore, or Less?

As Oriole Park hit full gear in its early years, many kept an eye on whether the surrounding area would develop and engage with it. The answer has been yes—to a degree. The ballpark didn’t sprout out of a dense neighborhood like Wrigley Field, as it’s more immediately surrounded by hotels and an expanded convention center. Ballpark-related commerce has been hit-and-miss; the very first ESPN Zone restaurant opened nearby at Inner Harbor, but shut down in 2010. More resilient is a series of pubs and restaurants wedged in between a Hampton Inn and a modern apartment complex across the street from the left field entrance; this area is more decked out for Orioles baseball, from the orange awnings outside of Slider’s Bar & Grill to the Brooks Robinson statue, erected in 2011 at a formal square across the street.

Walk a block west of Brooks’ statue and you’ll stumble upon the Babe Ruth Museum, located at the very house he was born. In fact, the whole area drips the legacy of Ruth, even if he never played for the Orioles (except for a minor league version back in 1914); from 1906-12, his father ran a tavern in a spot now occupied by Oriole Park’s center field; the family actually lived upstairs there for a time. The Orioles themselves pay official tribute to Ruth outside the Eutaw Street gate with a statue entitled “Babe’s Dream”, sculpted by local artist Susan Luery and unveiled in 1996. It’s best known for a subtle error: Ruth is holding a right-handed mitt, when it’s well known that he was left-handed.

Has Baltimore financially benefitted from Oriole Park? It depends who you talk to. It was estimated that over $50 million in revenue was brought into the city in the ballpark’s first year. Skeptics shrugged their shoulders and claimed it was simply money that would have been spent elsewhere. A John Hopkins study of Oriole Park’s early years said that expenses and taxes directly related to the ballpark exceeded revenue to the State of Maryland by $11 million.

Whatever the offset, there was no denying that Oriole Park became a boon to downtown, both economically and philosophically. And that was of great interest to other major league teams looking to build something new for themselves. Camden Yards became the default starting point for team reps and politicians going on nationwide field trips, scouting existing major league facilities to see what they liked and didn’t like. With Oriole Park, there was much to like—and little to dislike. Camden Yards clearly sparked a revolution, a gold rush of ballpark construction that borrowed heavily from its template of urban engagement and baseball heritage. Within two decades, all but a few major league teams had built their own variation of Camden Yards, while existing ballparks like Fenway Park, Dodger Stadium and Kauffman Stadium were rejuvenated with a Camden-esque touch. Oriole Park’s ingenuity bred habit upon everyone else.

The End of the Monopoly.

Baseball’s first ballpark boom since the steel-and-concrete era 80 years earlier would first be a blessing, then something of a curse, for the Orioles. Baltimore could field All-Star rosters throughout the 1990s because relatively abundant Camden Yards revenue gave them the freedom to do so. But that advantage gradually dried up as one retro ballpark after another sprang up, affording the same competitive opportunities to the teams that inhabited them.

The 2001 season, in particular, represented a turn for the worst for long-term Orioles fortunes and clearly proved that the rest of baseball was catching up—if it hadn’t already done so. Mike Mussina signed with the rival New York Yankees and, unfortunately for Baltimore fans, continued to win at Oriole Park whenever he returned in pinstripes. Hideo Nomo threw that no-hitter. The Orioles moved home plate back seven feet in the name of better fan viewing and relief for beleaguered pitchers (and also to accommodate a new and improved drainage system), but not only did the fans actually find it more difficult to see, so did the hitters as the batter’s eye behind center field wasn’t synched with a slightly re-angled field. Even Cal Ripken Jr. called it a day, ending a 21-year career in Baltimore. After posting winning records at home through their first nine years at Oriole Park, the Orioles were an atrocious 30-50 at the ballpark. For 2002, they moved home plate back to where it was before, as if to right the wrongs of a dreadful season. It didn’t work; the Orioles wouldn’t produce a winning record again at home for another eleven years.

This big-time funk wasn’t Oriole Park’s fault. The hits kept coming, as they had the day the ballpark opened—it’s just that most of them were coming off the bats of the Orioles’ opponents. The team’s ERA was a hair south of 5.00 from 2000-09, though it might have been quite a bit lower were it not for what the Texas Rangers did one night in 2007 when they tallied an AL-record 30 runs in the first game of a doubleheader. Oriole Park remained a wonderful place to admire and have fun, but the sting of constant losing eventually started discouraging would-be patrons; after the Orioles routinely drew 3.5 million fans during the 1990s, the new normal became something closer to 2.5 million, and it dipped even further, below two million, after the Montreal Expos moved to Washington, became the Nationals and siphoned away a good chunk of the Orioles’ D.C. fan base. Seas of empty seats became a jarring sight at a ballpark once used to sellouts; and it was particularly mind-boggling, in an April 2015 game against the Chicago White Sox, for the Orioles to play before a crowd of exactly zero—though that was less due to fan disinterest and more for security, as the ballpark became a virtual closed set as citywide civil unrest and rioting gripped Baltimore in the aftermath of the controversial police killing of an African-American in the city.

Oriole Park 2.0.

While the Orioles couldn’t upgrade themselves in the standings, they at least began to upgrade the ballpark here and there. In 2001 the left field foul pole from Memorial Stadium—which was still hanging around—was brought over because it was 20 feet shorter and wouldn’t obscure the view of upper deck fans. Two years later, there was an additional ode to Memorial with the placement, at the south end of the Eutaw Street plaza, of the old stadium’s Memorial Wall honoring America’s fallen soldiers. Brick was laid over the concrete backstop in 2004. And Janet Marie Smith returned in 2009 to oversee a three-year flurry of moderate improvements, including a reinvention of the lower two levels with wider seats and drinking rails (reducing capacity by 2,000), the installation in the left-center field plaza of six Orioles greats cast in bronze (including a second within a few blocks for Brooks Robinson), and the creation of the Roof Deck, a two-tiered, open-air lounge above the batter’s eye featuring a central bar, cushy sofas and views of both the game and Eutaw Street.

Fans pack Oriole Park’s main concourse during a rain delay. One of the ballpark’s chief complaints is that fans cannot see the action from the concourse; that may change in the near future. (Flickr—Austin Kirk)

Inside the ballpark, the food options are just as intriguing. Among the available concessions are hotdog favorite Polock Johnny’s (it’s okay—it was started by a guy from Poland), the Natty Boh Bar (that’s short for National Bohemian), and the Orioles have taken a twist on the all-you-can-eat section by placing it not in the cheap seats but, instead, the left-field portion of the club level. Here, not only do you get unlimited hot dogs, nachos, soda and salad, you also get access to the exclusive Club Level, forbidden to most other ticketholders. If peanuts aren’t your thing—put another way, if you’re allergic to them—the Orioles for certain games will allow the use of a “peanut-free” suite. All you need is a doctor’s note and $30, and you’re in. Finally, if you’d rather bring in your own food and drinks, the Orioles are one of the few teams to generously allow it—so long as the liquid is non-alcoholic.

Oriole Park at Camden Yards has deserved its place as a landmark achievement in the world of sports architecture and urban redevelopment. But as it approaches middle age, the question grows increasingly larger: Is it starting to look “old” in a bad way? Is it passé? Will the Orioles start hitting up politicians for a new joint, as some other teams with ballparks built after Oriole Park are already starting to do? Upgrades are sure to come; there’s talk of opening up the lower concourse so concession seekers can see the game while waiting in line—something most other new ballparks have accomplished.

At some point, sooner or later, ingenuity will strike again and someone will come up with The Next Best Thing in ballpark architecture. As habit dictates, everyone will be inclined to imitate it. This next boom will be the moment of truth for Oriole Park at Camden Yards; will it stand up to the new wave of ballparks and continue to retain its chic durability, as Fenway Park, Wrigley Field and Dodger Stadium have managed to do throughout their long lifespans?

If we don’t live to see the answer, then, chances are, there’s your answer.

The center field at the Coliseum seems to be a lonely place as a tall wall hides the rollout seats used for football. (Flickr—Ethan Bloch)

Baltimore Orioles Team History A decade-by-decade history of the Orioles, the ballparks they’ve played in, and the four people who are on the franchise’s Mount Rushmore.