THE BALLPARKS

Sportsman’s Park

ST. LOUIS, MISSOURI

Nestled at the corner of Grand and Dodier Avenues, the many iterations of Sportsman’s Park showcased a century’s worth of the best and worst of St. Louis baseball as the Cardinals cranked and Browns stank, where beer barons ruled and star hitters drooled within a hitter’s heaven. Its exhausting heyday put stress on a worn-out field and beat-up mesh screen that prevented home run records, allowing local fans to exceed their quota of National Pastime enjoyment.

It all began in 1866, barely a year after the Civil War’s final battle, with local ballclubs dueling on an unassuming plot of land accommodated by a minimum of bleacher space. It ended 100 years later with legends like Bob Gibson and Lou Brock thrilling crowds that topped 30,000, plus many more across the Midwest listening in to the action as called by Harry Caray and Jack Buck. In between, Sportsman’s Park was the center of St. Louis’ baseball universe, from Chris Von der Ahe’s in-play beer garden to the gluttonous batting prowess of Rogers Hornsby and George Sisler to a cameo by a 3’7” hitter because, what the hell—the Browns were already bad enough.

No major league ballpark was put through more everyday work than Sportsman’s Park, which from 1920-53 served as home for both the Cardinals and Browns. The field’s constant use and abuse made the thankless job of maintaining it most challenging for one Bill Stocksick, who looked over Sportsman’s field for an astonishing 60 years; given the wear and tear that led to constant cursing from ballplayers, it’s amazing that Stocksick lived to endure even half of his tenure.

For much of the hate directed at Sportsman’s Park by the players, there was also some love—much of it from the hitters who salivated over the ballyard’s cozy dimensions, particularly in right field where it measured 310 feet down the line and 354 to the gap. One look at the numbers and you’ll understand. The aforementioned Hornsby, a frequent .400 hitter during his peak years of the early 1920s, batted a career .392 at Sportsman’s. So did Ty Cobb in the 67 games he played there. In 104 games, Ted Williams hit at a .399 clip—banging out 33 home runs with 107 RBIs. Joe DiMaggio hit .389 with 45 homers and 156 RBIs—in just 127 games. Lou Gehrig, in 154 games—the equivalent of a then-full season—batted .360 with 52 homers and 157 RBIs. But Lefty O’Doul had them all beat; in 53 career games at Sportsman’s, he hit a mind-boggling .438.

Sportsman’s Park rarely enters the conversation of historic ballparks often monopolized by references to Fenway Park, Wrigley Field and Ebbets Field. Architecturally, Sportsman’s was not a wow, favoring function over aesthetics. Perhaps the venue’s most curious, and certainly rarely discussed, feature was its collection of third-party businesses facing Grand Avenue under the right-field bleachers, establishments that ranged from souvenir shops to a nightclub featuring striptease acts. Maverick owner Bill Veeck, in his few years attempting the impossible to make the Browns respectable, converted one of the units into his own apartment where he both lived and worked. In this sense, you can say that Sportsman’s Park was ahead of its time as a mixed-use facility.

Given its early birth date, one could say that Sportsman’s Park was well ahead of its time, period. Its field laid out five years before the start of the first organized leagues, Sportsman’s presence during baseball’s prehistoric times could have led to a more appropriate name: Jurassic Park.

The Fiefdom of Der Poss Bresident.

At the time of its first baseball activity, Sportsman’s Park was surrounded by prairie, two miles northwest of downtown St. Louis. But the area was undergoing aggressive urban development, as the city experienced a growth spurt during the 1860s that saw its population nearly double to 350,000; the emerging neighborhood was mostly populated by African-Americans as the city forbade them from buying land elsewhere within its limits. Sportsman’s didn’t even have a name at the time; one aerial illustration of the area, showing a rectangular plot surrounded by fencing and a few structures, simply listed it as “Baseball Park.”

Local teams gave way to St. Louis’ first major league experience when the Brown Stockings joined the National Association in 1875. By then, the ballpark had a name—Grand Avenue Grounds—and seating for 1,500. But the NA folded a year later, and so did the Brown Stockings after two years as a charter member of the National League—continuing on as a weakened independent team. The major league void remained for both St. Louis and the Grand Avenue Grounds until 1880, when two enterprising locals entered the picture. Albert Spink, six years away from starting up The Sporting News, hooked up with tavern owner Chris von der Ahe— an eccentric, portly young man whose German accent was as thick as his bushy mustache—and together they created the Sportsman’s Park and Club Association, from which they resurrected the freelance Brown Stockings back toward major league status.

Taking control of the team that would eventually become known as the Cardinals, von der Ahe sought to rebuild Grand Avenue Grounds and, accepting advice from Spink, gave it a new name—leveraging from their own entity to call it Sportsman’s Park. Although von der Ahe knew little about baseball, he had mastered the art of promotion, both for the Brown Stockings and himself, as he exclaimed himself as “Der Poss Bresident” and eventually built a statue of his likeness outside the ballpark. Capacity was expanded to 12,000, with a quaint, covered wooden grandstand topped by a smaller upper deck. All the other seats were uncovered, and that’s the way von der Ahe wanted it; basking in the hot St. Louis summer sun would encourage fans to buy more of the beer he sold not just at the ballpark but at a beer garden structure behind the right-field corner that was actually in play—meaning outfielders would have to go onto the premises and pardon the patrons to retrieve a live ball. By 1889, ground rules were drawn up so that any ball hit into the garden would be an automatic home run.

Joining the American Association for its maiden season in 1882 as a rival to the NL, von der Ahe’s Brown Stockings caught fire—winning four straight pennants from 1885-88—but unfortunately, so did Sportsman’s Park. A modest blaze damaged the beer garden and clubhouse in 1887, but another in 1891 was more destructive and set von der Ahe out to put together another ballpark some four blocks away. In 1893, New Sportsman’s Park—known in later years as Robison Field—was built by von der Ahe, who outdid himself by surrounding the new yard with a rolling bicycle track, water ride, artificial lake and, of course, a beer garden. The amusement park-like atmosphere chafed on his old colleague Albert Spink, who in his new rag wrote up an opinion piece entitled “The Prostitution of a Ballpark.” By this time, von der Ahe was wealthy enough to buy fire insurance—but dumbfoundingly, he didn’t. It cost him dearly when his new ballpark was devastated by yet another fire in 1898; the ensuing legal issues crippled him financially. A year later, von der Ahe sold the team; in 1913, he died flat broke.

Von der Ahe’s abandonment of Sportsman’s Park left it largely devoid of baseball for the bulk of the 1890s, with soccer matches and cycling on a surrounding cinder track taking over as the recreations of choice. In 1901, baseball returned briefly to Sportsman’s when the Cardinals—as the Brown Stockings were now known—endured another crippling fire at Robison Field. The team’s reunion with their old ballpark lasted one game; both the field and stands were so far beyond repair that the Cardinals threw up their hands and decided to stick it out on the road until their own park could be patched up.

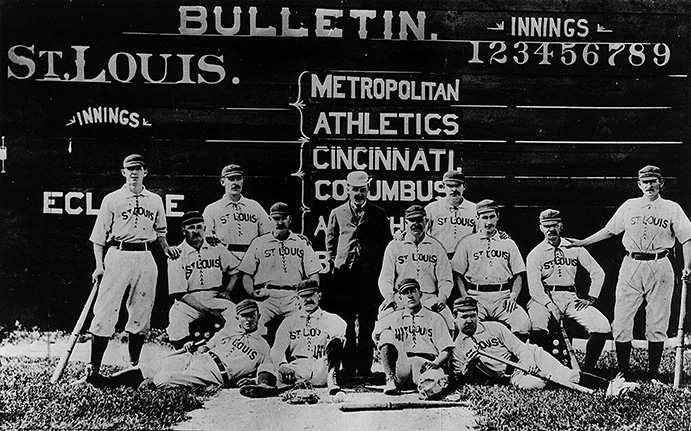

Members of the 1885 St. Louis Brown Stockings—later to be known as the Cardinals—pose in front of the Sportsman’s Park scoreboard in their first of four straight years winning the American Association title. (Missouri State Archives)

An Upgrade Here, an Upgrade There.

The Cardinals received competition—and Sportsman’s Park a new baseball tenant—when the American League’s Milwaukee Brewers moved to St. Louis in 1902. Sportsman’s initially wasn’t the first choice for dictatorial AL president Ban Johnson, as his efforts to secure land for a new ballpark in St. Louis were scuttled by greedy landowners who jacked up the acreage price at the eleventh hour. Out of options and almost out of time, Johnson came to a dilapidated Sportsman’s, hashed out a deal, upgraded the facility and crossed his fingers it would all work out.

A single-level wooden grandstand, covered between first and third base, circled around from near the right-field corner and straightened out down the left-field line. Fair territory was a skewed square shape, with the most extended side stretching from the left-field corner (342 feet) to right of center (roughly 440), backed by shallow bleachers that brought total capacity to 8,000. Right field served as more of a bandbox, with the right-field line measuring only 300 feet; in the Browns’ first seven years at Sportsman’s Park, only one player hit two home runs in a game, and of course he was left-handed—but the surprise was that the player was Branch Rickey, who would hit only one other homer in a short 120-game playing career before making a far bigger name for himself in the years to come as a trend-setting executive, starting with the Cardinals.

Sportsman’s Park was rethought in 1909, moving the field 90 degrees with home plate closer to the southwest end of the lot nearest the corner of Dodier and Spring Avenues, a field configuration that would stay for the remainder of the ballpark’s lifespan. Capacity was doubled to nearly 20,000; the covered grandstand from 1902 now served as a circular pavilion around the left-field corner, with a new double-decked structure molded out of steel and concrete, perpendicularly laid out around the infield with an angled corner behind home plate. Restlessly, the Browns made more changes in 1912, with the original grandstand torn down and replaced with a larger, covered pavilion. A similar but smaller structure filled in open space down the right-field line, facing the infield—with the roof actually poking out into fair territory. Though the tip of the roof lay only 270 feet from home plate—or some 40 feet in front of the foul pole—any fly ball landing on top of it within fair territory would be ruled a home run.

Over the 20th Century’s first two decades, the Browns would be the breadwinner between St. Louis’ two major league teams, frequently outdrawing the Cardinals despite repeated bad play from which they escaped the second division (fifth place or worse) only twice, with no pennants. Part of the reason was that the Cardinals were just as bad, if not worse.

The aforementioned Branch Rickey would change that.

High-Hittin’ Times.

In 1920, the Cardinals were bought by auto dealer Sam Breadon, who immediately didn’t want his team associated with the last remaining wooden ballpark in the majors. He bolted the repeatedly charred Robison Field and, for a negotiated annual rental fee of $20,000, moved into Sportsman’s Park. This began over three decades of multi-team tenancy, the longest in major league history.

The first decade of this shared usage would see both the Browns and Cardinals on the rise. One team’s ascent resembled a fleeting day hike; for the other, it was a trek into baseball’s Himalayas. The decade would also yield some of the most eye-popping levels of offense ever seen at the big-league level; as the 1920s would be referred to as the Live Ball Era, nowhere would the ball be as lively than at Sportsman’s Park. And nobody made it livelier than two Hall-of-Fame hitters at the peak of their careers.

From the end of World War I, the Browns gradually evolved from an also-ran to contender, with their first bona fide slugger in Ken Williams, solid support from outfielders Baby Doll Jacobson and Jack Tobin, and a true pitching ace in legal spitballer Urban Shocker. But the Browns’ best of show was George Sisler; while most everyone else was plugging in .300+ batting averages, the pitcher-turned-first baseman was frequently approaching, and topping, the .400 mark.

The Browns hit the summit in 1922 with the mightiest squad of their 52-year tenure in St. Louis. Williams clobbered 39 home runs with 155 RBIs, Shocker won 24 games, and Sisler—who two years earlier hit .407 on a then-record 257 hits—jumped it up to .420, the second highest batting average in AL history, even as a badly ailing arm handicapped him down the stretch. The team as a whole batted .329 at Sportsman’s Park, a figure surpassed in AL annals only by the 1950 Boston Red Sox at Fenway Park.

The gaudy numbers not only catapulted the Browns to the top of the standings, but the turnstile count as well with 712,918 fans, their highest total ever at Sportsman’s. One of those spectators unfortunately lobbed a bottle onto the field that struck the head of New York Yankees outfielder Whitey Witt in the first game of a crucial late-season series against the Babe Ruth-led powerhouse. The incident, which knocked Witt out of the game, deflated the enthusiasm and led to a bruising moment of comeuppance when, in the series finale, Witt singled home both the game-tying and go-ahead runs in the ninth inning. The Browns lost the game, the series, and the pennant at season’s end by one game to the Yankees.

The Cardinals similarly rose from the depths of the basement, evolving into a frontrunner within the NL’s ranks. Their approach to success was different; under Branch Rickey, the former Browns catcher now serving as the Cardinals’ manager and general manager, the Redbirds became the first team to engage a strong network of minor league affiliates, building from within and cultivating star players rather than plucking them away from other teams for enormous sums they didn’t have.

As the hits kept coming for the Browns’ George Sisler, the Cardinals would be even more blessed with Rogers Hornsby. The Texas-born second baseman, who claimed to avoid reading and watching movies because he wanted to preserve his eyesight for hitting the ball, won six straight batting titles as a Cardinal—and over a five-year period (1921-25) averaged over .400, checking in with a .425 mark at Sportsman’s Park. This included a .473 average in 1925—the highest recorded within a year by any batter at Sportsman’s—followed by a .469 figure in 1924, the year he established a modern NL mark at .424.

With Hornsby as player-manager in 1926 and Rickey moving exclusively to front-office duty, the Cardinals took their first pennant since their dynastical 1880s run as the Brown Stockings and stunned the Yankees in a memorable seven-game World Series. It would be the Cardinals’ first of seven world titles over the next 39 years at Sportsman’s Park, meriting a high level of sustainment—while the Browns’ shooting-star presence at the top would be followed by a near-eternal stretch of ineptitude.

Like other major league ballparks during the 1920s, Sportsman’s Park underwent expansion with the addition of a second deck to increase capacity to 34,000.

Wall Games.

The success of both teams during the 1920s prompted the Browns to enlarge Sportsman’s Park in 1926. The Cardinals initially protested the idea, but as renters had little say in the matter. Browns owner Phill Ball commissioned frequent ballpark builder of the time Osborn Engineering to add a second deck from pole to pole, and remake the right-field bleachers out of concrete, adding a roof on top. All box seats were torn out and replaced with fold-downs measuring 22 inches in width, considered quite spacious for the time. The $500,000 makeover increased capacity to 34,000—and gave Sportsman’s Park the structural look that would survive to its final days.

Another alteration attempted to bring sanity to the ballpark’s hitting madness. During a four-game series in 1929, the visiting Detroit Tigers walloped eight home runs over Sportsman’s right-field wall, which measured a cozy 310 down the line and only 354 to the gap. The powerful Yankees, with the iconic (and left-handed) Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig, were next on the home schedule. In response, the Browns quickly erected a mesh screen on top of the wall, roughly extending two-thirds of the way from the foul pole toward center and rising 21 feet to the bleacher roofline.

Ironically, the Monster Mesh’s first series hurt the Browns more than the Yankees. In the series’ second game, four of the five drives that contacted the screen were hit by the Browns—three by Heinie Manush, who settled for two doubles and a single when a week earlier it would have been a three-homer day. (Manush on the year hit only six homers.)

Three years later in 1932, Jimmie Foxx’s assault on Babe Ruth’s 1927 home run record was neutered by the big screen. Sources vary as to how many of Foxx’s long drives were knocked down by the screen; even Foxx’s own recollection changed through the years, stating that the number was anywhere from three to seven. Either way, it likely kept Foxx—who went deep 58 times that year—from surpassing the 60 belted by Ruth.

The big screen would stay for the remainder of Sportsman’s Park’s lifespan, with the exception of the 1955 season—a year that saw the most home runs (176) ever hit at the ballpark. Hall of Famer Stan Musial would smack 22 of his 33 homers that season at Sportsman’s for the Cardinals, making one wonder how much fewer he would have hit had the screen still been up—and how much more he would have hit, beyond his career total of 475, had the screen never existed.

Another enhancement that didn’t happen at Sportsman’s Park, to the consternation of outfielders, was the placement of padding upon its walls. Padding in general wasn’t used at major league ballparks until the 1940s, but there was something about the Sportsman’s Park wall that seemed to play with the heads of outfielders—both mentally and physically. It was a concrete barrier, nearly 12 feet tall, and contained small square windows or ornamentation spaced out every 20-to-30 feet. Thus, the make-up of the wall gave it an intimidating, fortress-like look akin to the interior of a prison yard. It certainly administered more than a few near-death sentences.

Earle Combs, the Yankee’s Hall-of-Fame leadoff man, was never the same after breaking both his skull and collarbone crashing into the wall in 1934. Neither was Brooklyn’s Pete Reiser, who looked headed toward Cooperstown when he, too, fractured his skull running into the wall in 1942. Perennial All-Star Bill White, in his first full year with the Cardinals in 1959, suffered a season-ending injury so brutal, The Sporting News claimed he “literally left his eyebrow” upon the impact area. And Minnie Minoso, early in his first year with the Cardinals in 1962 after 11 full-time seasons in the AL, broke his skull and wrist colliding with the wall—heavily curtailing the remainder of his Hall-of-Fame career. It took Minoso’s head-on to, finally, convince the Cardinals to pad the walls over its final few seasons.

Batting practice at Sportsman’s Park before a 1938 game. The large scoreboard in left field is in the process of being completed, while the flag pole remains in play in deep center field; it would be moved behind the wall starting in 1954.

Struggle at the Turnstiles.

St. Louis was hit particularly hard by the Great Depression, with unemployment soaring over 30%. This had an obvious impact on the Cardinals and Browns; annually throughout the 1930s, the two teams failed to draw a combined million fans to Sportsman’s Park—and there were four years where they couldn’t even group up to bring in half of that. The Browns, with the George Sisler era far behind, were reduced to a sad reality with nothing close to a winning record on the field and rudderless ownership off it, as the passing of Phil Ball in 1933 led to three seasons of the club being run by his estate. The gate reflected the Browns’ utter misery; three times during the 1930s, they drew less than 100,000—bottoming out at 80,922 in 1935. They attracted barely over a million fans for the entire decade.

On the flip side, at least results-wise, the Cardinals remained one of the NL’s more consistent contenders, winning three pennants—yet they, too, struggled at the turnstiles. When the Redbirds won their second world title of the decade in 1934, they attracted only 325,000 fans—the lowest total ever for a World Series champion in a full season.

As empty as Sportsman’s Park was during this time, the Cardinals could at least count on one fan to keep the place loud. Seated in the third row of Section 16 between home plate and first, Mary Ott was a pudgy, bespectacled middle-aged woman called the “Horse Lady of St. Louis” for her ear-shattering neigh that Collier’s Magazine described as that of a “misanthropic horse who has just thrown a thoroughly undesirable rider and stepped on his face.” There was nothing temperate about Ott’s personality or alcohol consumption; she downed numerous bottles of beer per game to keep her voice from going raspy. Ott would hold court at Sportsman’s Park from 1920 through the 1940s, vocally abusing one opponent after another. When the game was over, Ott would invite Cardinals players to her home, but it’s not what you think; she was married.

With attendance poor and money tight, the Browns kept Sportsman’s Park updated as best they could, with a few additions. A public address system was inserted in 1935, a new and larger scoreboard was set up behind the left-field bleachers, and lights were put in place in 1940 after five years of dilly and dally, as the Browns and Cardinals wrangled in constant negotiation over how much each team should pay for the installation.

The depression laid quite a financial toll on both clubs, and there always seemed to be speculation regarding the Cardinals leaving Sportsman’s Park for either their own ballpark or another city as St. Louis continued its long struggle to support multiple major league teams. But in 1941, the Browns began serious plans for their own, rather ambitious departure to Los Angeles. All the logistics and transferal of territorial rights were taken care of, and the Cardinals were even ready to stuff $250,000 into the Browns’ pockets to help boot them out of St. Louis. With their bags all but packed, the Browns only needed the formality of AL approval; a vote was scheduled for December 8. But the day before ended up living in infamy, as Japan attacked Pearl Harbor—leaving the West Coast vulnerable to an invasion. The deal was off, and the Browns remained stuck at Sportsman’s Park.

The Beneficiaries of War.

The derailed plans of the Browns’ California move only deepened the assumption that America’s plunge into World War II would knock back any ongoing progress that the Cardinals and Browns hoped to experience after being so financially beat down by the depression. But the war would actually serve to enhance both clubs in different ways.

With major league talent having been snapped up by the U.S. Armed Forces, the Cardinals had the advantage of relying on their vast minor league system to keep their roster bulked up while other teams struggled to find replacements. The Cardinals thus became a wartime juggernaut, perennial 100-game winners nabbing three straight pennants and two world titles from 1942-44. More shockingly, the Browns also benefitted; the loss of veteran players among the better clubs led to a shakeup of power within the AL, giving the Browns something of an even chance to compete—even if admittedly on a more inferior playing level.

Stocked with true major leaguers rejected by the military for various miscellany (flat feet, sinuses, etc.), the Browns shocked what was left of the baseball world in 1944 by winning their one and only pennant during their half-century St. Louis tenure. For one season, Sportsman’s Park became a happening place for the traditional losers, taking the AL flag on the season’s last day with a 5-2 victory over the heavily depreciated, momentarily no-name Yankees before a crowd of 35,518—the largest-ever regular season gathering for a Browns game at Sportsman’s, with 20,000 turned away. Despite ruling the AL, the Browns would remain the second best ballclub in St. Louis; at the World Series, they met up with their co-tenant in the Cardinals, who took the series in six games, all of them sellouts at Sportsman’s Park.

Another positive and long-overdue development at Sportsman’s Park during the war was the decision to integrate the ballpark. Located in what was once a slave state during the Civil War, Sportsman’s Park was the last remaining major league ballpark to restrict seating for African-American spectators, confining them to the right-field bleachers. Though Negro League teams were based in St. Louis, none of them ever played at Sportsman’s; a lack of vacancy, with the Cardinals or Browns using the venue every day, probably had more to do with that than racial bias. In 1941, when the famed Kansas City Monarchs and legendary pitcher Satchel Paige came to St. Louis for an exhibition against the Chicago American Giants, Paige refused to take part unless the game was held at Sportsman’s—further insisting that black fans be allowed to sit anywhere they pleased. Paige was accommodated, and 20,000 showed up to watch the Monarchs win in a rout, 11-2. It would be another three years before Sportsman’s opened up the rest of the ballpark for black fans at games featuring the Cardinals or Browns.

This is not an exhibition: All three feet and seven inches of Eddie Gaedel bats for the St. Louis Browns in an actual 1951 game against the Detroit Tigers. Gaedel would walk on four pitches because, in part, his diminutive stature made the strike zone so small. The Gaedel at-bat was perhaps the most notorious stunt of owner Bill Veeck’s short tenure trying to make the Browns into a winner; unable to do so, he sold to a group that in 1954 moved the franchise to Baltimore.

Brown Out.

When war ended and baseball’s star players returned in 1946, fans came flooding back to Sportsman’s Park for the Cardinals—but not the Browns. The Cardinals drew over a million fans for the first time and triumphed in baseball’s first postwar World Series, being taken to the limit by the Red Sox before prevailing in seven games. The Browns, on the other hand, were knocked back to their real-world existence as perennial cellar dwellers, experiencing barely a trickle of an uptick in attendance while the rest of baseball nearly doubled its gate.

It was hard to tell whether the Browns were bringing down Sportsman’s Park, or vice versa. The near 50-year-old facility was not aging well; critiques were growing louder. “I’ve played in better Class-D ballparks,” spouted the New York Giants’ Phil Weintraub. Teammate Rube Fischer added that walking into the visitors’ clubhouse was like entering a “cheap hotel.” And Yankees manager Joe McCarthy spoke for too many people when he compared the rough, overworked infield to a beach.

Richard Muckerman, who had bought both the Browns and Sportsman’s Park late in 1945, heard all the complaints and decided to do something about it. He gave the ballpark a long-overdue makeover; he added two additional spectator ramps, more restrooms, separate dressing rooms for the umpires and trainer, a private office for the manager, an auxiliary scoreboard on the first-base side, an elevator hoisting sportswriters to a new, larger press box atop the second-deck roof, and a “penthouse” lounge for himself and guests. The budget for the upgrade was initially set at $180,000, but when Muckerman was done, it had ballooned to four times that cost. While it certainly made Sportsman’s Park a better place, it didn’t make the Browns a better team. But by now, no one could make them better anyway.

Certainly not Bill and Charley DeWitt, brothers who bought out Muckerman in 1949, hired a hypnotist to jumpstart the Browns (that didn’t work), and sued the Cardinals for higher rent because they were drawing three times as many fans to Sportsman’s Park. A judge all but laughed the Browns out of court, stating that the team’s argument was “a hindsight rationalization of what it would have liked the lease to be.”

Not even Bill Veeck, the master showman of baseball, could turn the Browns around. Purchasing from the DeWitts in 1951, Veeck attempted the same magic he forged at Cleveland three years earlier when the Indians won a world title and drew just short of three million fans with an endless parade of promotions that would have made Chris von der Ahe jealous.

At least Veeck made things interesting—even audacious—at Sportsman’s Park.

Just a month after buying the Browns, Veeck helped celebrate the franchise’s 50th year with a circus-like atmosphere memorably highlighted with the appearance of 3’7” Eddie Gaedel as a pinch-hitter against the Detroit Tigers. Wearing uniform number 1/8, Gaedel never swung the bat and drew four pitches outside of a strike zone recalibrated and vertically squeezed for his much smaller frame, taking the walk and departing for a pinch-runner.

In another crazy stunt five days later, Veeck wanted to “rest” manager Zack Taylor and replace him with two randomly chosen fans. The AL suppressed the request, and Veeck settled on a Plan B in which he handed out placards that said “Yes” on one side and “No” on the other to a crowd of 4,000, who decided on matters of strategy during the game. It worked, if only for one night; the Browns beat the Philadelphia A’s, 5-3, with Taylor quietly witnessing the scene from a rocking chair in the front row.

Like the Browns, the Cardinals’ ownership was experiencing its own round of musical chairs. Fred Saigh, who had bought the club in 1947 from Sam Breadon, was forced to sell in 1953 after being given a 15-month prison term for tax evasion. Stiff-arming efforts by deep-pocket Houston interests intent on buying the Cardinals and moving them to Texas, Saigh stayed faithful to the locals and, at a reduced price, sold the team to Augustus “Gussie” Busch III, lord of the St. Louis-based brewing giant Budweiser.

Busch provided stronger and more corporate competition to Veeck, who now needed a get-out-of-St. Louis card after failing to boost the Browns at the gate or within the AL standings despite his bag of promotional tricks. He first sold Sportsman’s Park to Busch for $800,000, then began efforts to move the team. But the other, more conventional AL owners, tiring of his carnival act and enraged over his strong-armed tactics to conjure up broadcast revenue sharing—which would clearly benefit the needy Browns—denied his every request to relocate, hoping to suffocate him out of baseball. The ploy worked; at the end of the 1953 season, Veeck caved and sold the team for $2.475 million to a Baltimore group. Aware of the deal, a crowd of 3,174 showed up at Sportsman’s Park for what would be the Browns’ last game—fittingly, their 100th loss of the year—and took its anger out of Veeck, hung in effigy from the upper deck with a sign that read, “Bill Wreck.” The Browns became the Baltimore Orioles, and the Cardinals had St. Louis—and Sportsman’s Park—all to themselves.

A color postcard image of Sportsman’s Park from the late 1950s, when the ballpark was called Busch Stadium. To the right of the press box, under the upper-deck overhang, are suite-like units added as part of a 1954 makeover. (Missouri State Archives)

Bring on the Clydesdales.

Gussie Busch didn’t waste any time performing a $1.75 million upgrade on Sportsman’s Park. He replaced all the seats, constructed eight “private compartments” (suites) beneath the upper-deck overhang complete with lounge chairs, lockers and phones, and added restrooms and drinking fountains. Additionally, an organ was installed, performed by the wife of former Cardinals catcher Joe Garagiola, and the massive scoreboard behind the left-field bleachers was modified to include a large Budweiser logotype topped by the Anheuser Busch crest, complete with an eagle electronically going into motion after each Cardinals home run.

As much as the fans enjoyed their enhancements, the players were overjoyed with the improvements they experienced. The clubhouses were overhauled and expanded, with the home side getting a special lounge; dugouts were modernized and elongated; player safety was improved with the addition of a warning track in front of the brutal concrete wall, and the relocation of the flag pole, in play deep in center field, behind the wall. The center field bleachers were taken out and replaced with shrubs to provide a better batting backdrop—as if hitters needed more advantage in a ballpark that already favored them. Finally, the Browns’ departure allowed the playing field to recover and remain in top shape; a new drainage system helped out as well.

Busch’s makeover also included a name change. Originally, he wanted to rename Sportsman’s Park as Budweiser Stadium, but the idea was met with furious opposition from both fans and Busch’s fellow owners who highly disliked the idea of a corporate name—especially one promoting beer—slapped on a ballpark. Busch quickly conceded and settled for Busch Stadium, then slyly went about creating a new brand of suds called Busch Bavarian Beer. State law prevented Busch from selling his own beer at a facility owned by a brewer, so he got around it by hiring a third-party concessionaire to sell it for him—making sure, with a wink and a nod, that his Budweiser brands would be sold at a cheaper price than his competitors. Further providing advantage for his beer, Busch removed all the ads around the ballpark—leaving only the large Budweiser signage above the main scoreboard.

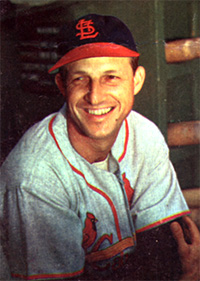

The smile never seemed to wear off the face of Stan Musial, the most beloved player at Sportsman’s Park. Though he generated the same number of hits (1,815) at Sportsman’s as he did on the road, he batted 10 points higher (.336) with 29 more home runs (252) at home; his 1,056 RBIs at Sportsman’s make him only one of two players to knock in over 1,000 in one ballpark. (The Rucker Archive)

Throughout the 1950s, the Cardinals were an enjoyable if not highly competitive team, finishing somewhere in the middle of the NL standings, rarely contending but never falling apart. The ballclub’s undisputed matinee idol of this time was Stan Musial, the easygoing, sweet-swinging Hall of Famer who played 22 seasons, made the All-Star roster every season except his first two, never lost his smile and never once got ejected from a game. Among Musial’s many highlights were the five home runs he smashed in a 1954 doubleheader at Busch Stadium, his last of seven batting titles in 1957 at the age of 36 (hitting .351), and his final two homers hit in 1963 after becoming a grandfather. He’s only one of two players (Carl Yastrzemski being the other) to knock in 1,000 runs in one ballpark, bringing home 1,056 at Sportsman’s Park/Busch Stadium. Musial’s box office pull was one of the reasons the Cardinals were consistently drawing a million fans, give or take a couple hundred thousand, every year during the height of his fame.

Further enhancing the Cardinals’ popularity were the great radio voices that reached listeners across the Midwest on 50,000-watt KMOX, reeling in new fans near and far. In the early years it was former ace Dizzy Dean, whose deep Southern butchering of proper pronunciation proved popular with listeners but grated on local English teachers; by the 1950s, the booth included broadcast legends Jack Buck, Joe Garagiola and Harry Caray—who reveled in the first of the team’s broadcasts from the Busch Stadium bleachers in 1958, taking off his shirt and buying buckets of beer for surrounding fans.

Bookended by the Pigskin.

Whereas many of the steel-and-concrete ballparks built early in the 20th Century performed double duty hosting pro football teams, Sportsman’s Park stayed largely quiet in the Fall except for soccer, a sport with healthy local representation in St. Louis. Early gridiron history was made at Sportsman’s from its first football tenant, Saint Louis University—coached by Eddie Cochems, considered the father of the forward pass. in 1906, Cochems’ newfound use of the passing game resulted in an 11-0 record, outscoring the opposition 407-11.

Two very short-lived NFL teams came and went at Sportsman’s Park early in the league’s history, but in 1960 the more established Chicago Cardinals transplanted themselves to St. Louis, giving Busch Stadium two sports franchises with the exact same name. To accommodate the football Cardinals, temporary bleachers seating 8,133 were erected in left field to help buffet a field running from the third-base line to the right-field wall. Ticket sales were in line with the Cardinals’ sluggish performance, and the owners grew antsy enough to publicly consider another move out of town—but were seduced into staying when, in 1962, St. Louis voters approved funds to build the bigger, more modern and multi-purpose Busch Memorial Stadium south of downtown.

A panoramic shot of Sportsman’s Park (Busch Stadium) during the 1964 World Series against the New York Yankees. The large Budweiser scoreboard was the only form of advertising within the ballpark—a choice made by Cardinals (and Anheuser Busch) owner Gussie Busch. (Missouri State Archives)

“Drop the Ashes on the Floor.”

Busch Stadium’s final few years saw the baseball Cardinals return to championship form, prioritizing strong pitching (Bob Gibson), defense (perennial Gold Glove winners Curt Flood and Bill White), and speed (Lou Brock) over the slugging of the retired Stan Musial. The relative “small ball” philosophy wasn’t tailor made for hit-happy Busch, but the Cardinals proved that their newly-embraced skillset could win in any ballpark, winning their final World Series at the old ballyard in 1964 with a seven-game conquest of the Yankees.

For its final full season in 1965, Busch Stadium was given a fresh coat of paint, new turf including a softer infield, and more diverse food items at the concession stand. It was like dressing up a corpse for a season-long funeral. Though expected to be the Cardinals’ last year at the ballpark, construction delays pushed back the opening of Busch Memorial Stadium, forcing the team to play its first 10 games of the 1966 campaign at Busch exactly 100 years after the first baseball played at the site. The Cardinals played like a team with a lame-duck attitude, losing seven of those 10 contests—including their last four. Even the fans were ready to move on; a half-capacity crowd of 17,503 showed up for the final game, a 10-5 loss to the San Francisco Giants. After the final out, a ceremony convened with Bill Stocksick, the long-time groundskeeper who had retired just a couple years earlier, digging up the same home plate he planted way back in 1905 and watching it delivered via helicopter to Busch Memorial Stadium.

The Sporting News tells the story of a moment afterward in the St. Louis clubhouse. Stan Musial was paying a visit to his pal, former teammate and current Cardinals manager Red Schoendienst. Musial pulled out a cigarette, lit it, and asked Schoendienst for an ash tray.

“Drop the ashes on the floor,” said Schoendienst. “They’re going to tear the place down tomorrow.”

Now Playing: The Boys, the Girls, and the Ghosts.

After 100 years, 7,836 games, 15 pennants and seven World Series triumphs, Sportsman’s Park was promptly demolished. The ballpark had grown old, and so had the surrounding area. It was also dangerous to boot, with several shooting incidents including the holdup of an outside ticket office during a game in the late 1950s; one round of gunfire barely missed Cardinals third baseman Ken Boyer inside the park.

Today, the property is home to the Boys and Girls Club of Greater St. Louis. A plaque in its lobby honors Sportsman’s Park, while a football field outside takes up most of the ballpark’s former footprint; from above, the scars of the old ballfield can still be seen. A smaller baseball field is one block over. The neighborhood has not improved, though nature is slowly winning the battle against poverty and crime with an abundance of tall, grassy lots where homes once stood. A single woman on Reddit recently posted that she was considering moving to the area and wanted to know what it was like. Most responses quickly warned her to consider another area.

Amid the Boys and Girls club and the surrounding blight speckled with a hint of future gentrification lie the ghosts of St. Louis’ baseball past—from Chris von der Ahe and Charles Comiskey to George Sisler, Rogers Hornsby, Dizzy Dean, Stan Musial and Eddie Gaedel. If you see any of them hanging around, pinch yourself that it’s not heaven—or Iowa—but be in comfort of the fact that these gentlemen gave their heart and soul to a ballpark that saw great times, awful times, and a whole lot of the in-between.

The Ballparks: Busch Memorial Stadium Yes, Busch Memorial Stadium was a “cookie cutter” venue, but a good one—and one that aged fairly well once the Cardinals ripped out an artificial turf you could fry eggs on and planted natural grass beholding unnatural sluggers, cheered on by a loyal red-clad fan base whose enthusiasm was as strong as the 96 arches that topped the stadium were graceful. After years of rickety Sportsman’s Park, Busch Memorial provided a gateway to modern times in St. Louis.

The Ballparks: Busch Memorial Stadium Yes, Busch Memorial Stadium was a “cookie cutter” venue, but a good one—and one that aged fairly well once the Cardinals ripped out an artificial turf you could fry eggs on and planted natural grass beholding unnatural sluggers, cheered on by a loyal red-clad fan base whose enthusiasm was as strong as the 96 arches that topped the stadium were graceful. After years of rickety Sportsman’s Park, Busch Memorial provided a gateway to modern times in St. Louis.

St. Louis Cardinals Team History A decade-by-decade history of the Cardinals, the ballparks they’ve played in, and the four people who are on the franchise’s Mount Rushmore.