THE BALLPARKS

Tropicana Field

St. Petersburg, Florida

(Flickr—City of St. Pete—Modified from Original)

Build it and they will come. Maybe. The good folks of St. Petersburg waited and waited and waited until, at long last, the Devil Rays swam upon the scene to put Tropicana Field, tilted lid, catwalks and all, upon the major league map. But as the Trop flopped, other good folks asked, why did they build this? And why did they build it here? It’s a grapefruit-sized case of location, location, frustration.

To any outsiders on their way to St. Petersburg to watch baseball at Tropicana Field, a geography lesson is in order. They probably already know that the Trop is not going to be Fenway Park, and that the Rays, more likely than not, are not going to be the Red Sox. But once they arrive at what is the majors’ last remaining fixed domed structure, they’ll understand why the Rays are such a tough draw. And it’s not entirely about the Trop’s reputation or the performance of its home team.

Tropicana Field lies just blocks away from tiny downtown St. Petersburg, which itself lies near the south end of its city limits. But the city in general is surrounded on three sides by water, which requires long bridges for the majority of the region’s residents to make landfall. Even once they do, they next need to navigate through congested traffic on I-275, the city’s lone major thoroughfare. Long story short: For all those potential fans living across the bay, the Rays might as well be playing in St. Petersburg, Russia.

Bad location is only one of the issues brought up when people cite the bad rap on Tropicana Field. The early ineptitude of the expansion Devil Rays severely stunted the early momentum of attracting baseball fans starved for major league ball before the team’s arrival; a new owner, a brand correction and colorful manager Joe Maddon chipped away at the handicap and stunningly brought Tampa Bay an unexpected pennant in 2008, but consistent success has remained elusive in a market that’s mid-sized at best, compounded by the fans’ eternal commute to the ballpark.

Then there is the Trop itself. Designed and built on the eve of the retro ballpark craze, the venue became unfashionable almost as soon as it opened. Even after getting a sizeable makeover for the Devil Rays’ 1998 debut, Tropicana Field simply continued to lack most of the positive features of other post-Camden Yards parks, entombed without real grass, blue skies and panoramic views of its surroundings. Further updates were more cosmetic than structural; there’s only so much lipstick you could put on a pig before you admit that, yes, a pig is a pig is a pig.

The bottom line for the movers and shakers of St. Petersburg is that they built it and they came—eventually. So, objectives achieved. While the pride may be short-lived as the Rays look elsewhere to play, they can at least take comfort in giving life to the team and the summer game in the region.

The interior of Tropicana Field. Note the random clutter of advertising and faux facades above the bleachers from center to right. (Flickr—City of St. Pete)

It Came from the Lake.

Baseball is certainly no stranger to St. Petersburg. For over 100 years it’s been an active home for spring training activity; it all started in 1914 when the St. Louis Browns became the first of nine major league teams to eventually base their Grapefruit League camps within the city. Beyond that, pro sports in the region had been lacking until the 1970s, when two franchises were secured in Tampa: Football’s Buccaneers—which made news by losing their first 26 games—and the North American Soccer League’s Tampa Bay Rowdies, a spirited (albeit brief) success with crowds averaging as high as 30,000.

While this modest influx of sports gained Tampa national recognition, its rival across the bay quietly moseyed about like a poor second cousin. Beyond the beaches that drew retirees and rowdy spring breakers, there wasn’t much to get thrilled about in St. Petersburg. “God’s Waiting Room,” wrote author Bob Andelman. “A pinched Albanian village,” opined the Tampa Tribune, never one to pass up an opportunity to take a shot at its neighbor. “Everybody down there looks like George Burns,” penned Chicago Tribune columnist Mike Royko.

Perhaps seething from the insults, St. Petersburg Times publisher John Lake decided it was time for a rebuttal. Speaking at a local Chamber of Commerce meeting early in 1977, Lake planted the seed for building a St. Petersburg ballpark—not another spring training yard, but a full-fledged facility that would attract a major league team to play games that actually counted in the standings.

Lake’s sermon became chatter, and chatter became action by 1980 when the Pinellas Sports Authority was established by state politicians with a $125,000 budget to determine potential sites for a ballpark. Initially, the PSA thought big; besides a ballpark, they were envisioning an expansive sports complex that also included county fairgrounds, a track-and-field facility, tennis courts, pools—even a grand prix racing course. The Authority found three locations it liked—all on the north end of St. Petersburg, a natural conclusion given its closer proximity to Tampa.

An early vision of a St. Petersburg ballpark was to build an open-air facility stretched over by a tent-like roof.

Funding to help the project get moving had to come through acknowledgment from the Pinellas County Commission, which initially voted 3-2 to support the Gas Plant site. But one of the commissioners who gave thumbs up faced a backlash from his constituents for his decision and was voted out; his anti-ballpark successor became part of a new vote which swung the count 3-2 against the project. The PSA sued, claiming the PCC had already bound itself to an agreement and couldn’t change its mind. The courts agreed, and the ballpark project, after a good deal of tension, was back on.

The final say had to come from St. Petersburg itself. The ballpark was tied to a $750 million redevelopment price tag, and six of nine councilmembers thought that was win-win enough to nod their approval and move forward. To sidestep a public vote, no residential tax money would be used; it would come instead from hotel, cigarette and gas taxes. And as for the residents of the Gas Plant, who faced eviction? By and large, they approved of the ballpark. The relocation money offered by the city was too good to say otherwise.

Tampa-ering.

As if St. Petersburg needed any more grief, it got it anyway from its jealous rival to the northeast, Tampa. There, the idea of a ballpark was still in the dream stage—but they had big hitters with deep pockets willing to make it real. As this collection of rich businessmen known as Tampa Bay Baseball Group was drawing up plans for a new ballpark near Tampa Stadium, it aggressively set out to purchase an existing big league team to eventually fill it.

In 1984, TBBG purchased 42% of the Minnesota Twins, whose owner Calvin Griffith was grumbling over poor attendance at the recently opened Metrodome. The hope was that Griffith would sell his remaining share of the team to TBBG so it could be moved to Florida, but Minneapolis business leaders stepped up to buy the team in whole and keep it in Minnesota. TBBG later had handshake agreements or better with the Oakland A’s and Texas Rangers, but those deals fell through when local interests also stepped up.

Meanwhile, TBBG wielded whatever pressure it could upon St. Petersburg to make it think twice about building its new ballpark. It sicced the Tampa Tribune to write derogatory articles about both the project and St. Pete. It lobbied New York Yankees owner George Steinbrenner, a Tampa resident, to dissuade St. Petersburg officials. When that didn’t work, Steinbrenner got baseball commissioner Peter Ueberroth to wire St. Petersburg mayor Bob Ulrich. In short, Ueberroth’s message was this: Just because you’re building a ballpark doesn’t mean you’re allowed to cut to the front of the expansion line.

Undeterred, St. Petersburg plunged the shovels into the ground to start building the ballpark late in 1986. With construction ongoing, the venue would be given its first name after the St. Petersburg Times held a public survey that attracted 20,000 responses. The winning name: Florida Suncoast Dome. Runner-up: Suncoast Dome.

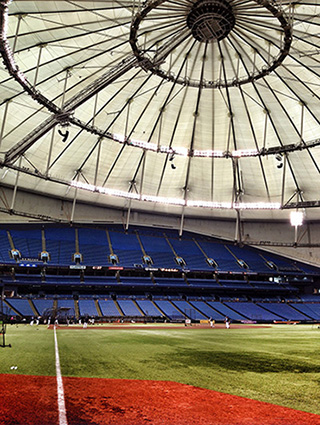

Early designs from Kansas City-based sports architect HOK Sport revealed some interesting thoughts, none of which made the final cut. One idealized a facility mostly covered by a tent-like canvas, providing maximum shade while allowing natural breezes (and humidity) to flow through. The winning design called for an enclosed structure with a dome tilting downward toward the northeast at 6.38 degrees. There were two reasons for the slant: To better protect the Teflon-coated roof during a hurricane (which typically strikes from the south or southwest) and to save on air conditioning costs, as it would have less space to cool in the lower end.

Initially, the Florida Suncoast Dome’s main entrance would be placed on the southwest side—an interesting choice given that the main parking lots would be on the other side of the building. Six equidistant pedestrian corkscrew ramps surrounded and adjoined the structure, which had a bland vanilla exterior wall that extended out beyond another below it. Imagine a pot with an oversized lid thrown on it at an angle, and you get the idea.

Outside of an unexpected add-on tab of $8 million to clean up contaminated soil from the Gas Plant’s industrial heyday, construction of Florida Suncoast Dome went smoothly and wrapped by 1990. By then, Tampa Bay Baseball Group saw the light and finally had its Come to St. Pete moment. After all, for a city to secure an expansion franchise, you need a ballpark and money. St. Petersburg had the former, TBBG the latter. It made perfect sense for the two entities to finally shove the sibling squabbles aside and join forces.

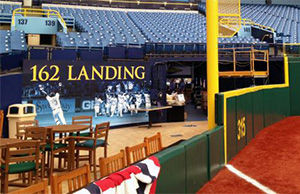

Looking down the left-field line at Tropicana Field. The second level of bleachers, officially named the Party Deck, was added as part of the venue’s $85 million upgrade to welcome the Devil Rays in 1998. (Flickr—City of St. Pete)

Baseball’s Favorite Bargaining Chip.

St. Petersburg got the ballpark. Now it just needed a team. Little did it realize that building Florida Suncoast Dome would end up being the easier chore.

While the major leagues dragged their feet on expansion through the 1980s, there were some established teams expressing frustration over their current situations. In Chicago, the White Sox were unhappy with what little progress was being made on securing public funding for a new ballpark to replace aging Comiskey Park. In 1988, their annoyances came to a boil; build us a new park, they warned, or we’re moving lock, stock and barrel to St. Petersburg. Finally, something from the major league establishment that was music to St. Pete’s ears.

The burden fell upon the Illinois State Legislature to save the White Sox from leaving. On June 30, 1988, it was do or die; if funding for a new Chicago ballpark didn’t pass by midnight, the White Sox would be St. Petersburg’s. As the deadline approached, the votes just didn’t look to be there. When the clock struck 12, they still weren’t there. Except the clock never struck 12; the governor had literally stopped time to buy more of it and, therefore, more votes. He succeeded, the measure passed a few minutes after midnight when it really officially wasn’t, and wink-wink, nod-nod, the White Sox stayed in Chicago. “Richard Daley is far from dead,” lamented the St. Petersburg Times’ Hubert Mizell.

Shortly after the White Sox’ juke, baseball finally announced it would expand. Naturally, most everyone assumed St. Petersburg would be a prime candidate. Major league owners assumed otherwise. In June 1991, two new National League franchises were named, with St. Petersburg left out in the cold. Adding insult to injury, one of the new teams would be the Miami-based Florida Marlins—a move that owners probably saw as a way to get people to stop asking, “When will you put a team in Florida?” Somewhere, Peter Ueberroth was uttering, “I told you so.”

The sting of losing out on expansion was temporarily eased a few months later when the Seattle Mariners came calling. Owner Jeff Smulyan, who had just bought the team two years earlier, had a newer stadium in the Kingdome but few people passing through its turnstiles—and he was losing a lot of money. Smulyan put the team on the market and stated that if no local buyer came forward, he’d sell to St. Petersburg. A hero came forward not from the Northwest but Japan—where the head of Nintendo bought the Mariners and vowed to keep them in Seattle.

A year later, it was the San Francisco Giants’ turn. Owner Bob Lurie had grown to detest arctic, wind-swept Candlestick Park—who didn’t—and was desperately trying to build a new ballpark somewhere, anywhere in the Bay Area. But after local voters declined four different ballpark measures, Lurie was done. He didn’t just threaten a move to St. Petersburg, he made good on it—selling it to remnants of Tampa Bay Baseball Group and the various St. Petersburg-area agencies. Few other major league owners didn’t want the move to proceed—not the Los Angeles Dodgers, whose arch-rivalry with the Giants would be neutered three time zones apart, and certainly not the expansion Marlins, who wanted Florida to themselves. But they had no choice; there was no other buyer to sell to. Until, that was, San Francisco politicians desperately dredged up enough willing investors to establish an ownership group and make a counter-offer. Never mind that St. Petersburg’s bid was 20% higher; baseball owners, led by then-interim commissioner Bud Selig and his proclamation of “the best interests of baseball,” approved the deal keeping the Giants in San Francisco.

Like a spurned bride left at too many altars, St. Petersburg finally got mad. The city sued Major League Baseball for $3 billion and challenged its longstanding antitrust exemption that allowed the lower bid on buying the Giants. The hidden message within the suit was plain: Give us a team, or we’ll sue for one.

Everything but Baseball.

For the first eight years of its existence, the Florida Suncoast Dome hosted just about every conceivable type of activity except for the one it was built for: Baseball. But at least it led a busy life.

For its very first event, on March 3, 1990, the facility hosted something akin to a variety TV show on steroids. The program included marching bands, hundreds of dancers, fireworks and a laser light extravaganza; the evening was capped off by a Kenny Rogers concert. Over 29,000 came out and viewed a rather Spartan looking facility with three decks of seats from (missing) foul pole to foul pole, a single level of outfield bleachers set against a tall, bland wall, no scoreboard and no interior personality. Even the turf was missing; the evening’s participants performed on a concrete floor.

Tropicana Field’s roof is held up with the help of four rings or “catwalks,” the top two of which are always in play should a high fly ball make contact. (Flickr—WestonStudioLLC)

The Dome’s first two tenants were unlikely ones: The Tampa Bay Storm of the Arena Football League, and the expansion Tampa Bay Lightning of the National Hockey League. Both teams were accommodated within the larger facility by having bleacher seats moved inward toward the fixed seats to form cozy seating around the playing area. Both teams also drew very well; the Storm, which played from 1991-96 at Florida Suncoast, averaged anywhere from 15,000-20,000 fans per game, while the Lightning—whose brand perpetrated the venue’s first name change, to the Thunderdome—averaged 19,000 a game over three years with inexpensive tickets that were easily the NHL’s cheapest. On April 23, 1996, the Thunderdome’s expansive hockey capacity was responsible for helping to attract a crowd of 28,183 for a playoff game—the largest for any NHL contest before the league began playing specially scheduled outdoor games in 2003.

Behold, the Devil Rays.

With the potential elimination of the antitrust exemption hanging over its heads, Major League Baseball finally ran out of excuses and, on March 9, 1995, blessed the city of St. Petersburg with an expansion team to be called the Devil Rays. Even though the Thunderdome had been built for baseball, it lacked just about everything necessary for it; there was no scoreboard, foul poles, dugouts or even clubhouses. But that was the tip of the iceberg for a ballpark whose austere environment was badly in need of a sprucing up. So the Thunderdome was shut down for 17 months and $85 million spent to give the facility a major facelift and yet another new name.

Seats were added to the field level—including 100 virtual upholstered recliners behind home plate, complete with monitors where fans could order food and access stats—while others were subtracted from the second “club” deck to make way for luxury boxes. A wide party deck was inserted above the left field bleachers. The main field level concourse was widened at the west and east end as the structure was extended outward and given light with a slanted, tinted glass roof. Within the widened concourse, a virtual mall had been developed that included a year-round restaurant behind the batter’s eye in center field, a bank, a travel agency, a climbing wall—even a cigar bar. Better a mallpark than a dullpark.

Panache was added to the outside as well. Righting a previous wrong, the Devil Rays moved the main entrance to the east side of the ballpark, facing the main parking lot. Not only is the walk to the front door shorter, it’s more decorative; a main walkway splits the lot and is adorned with 1.8 million small tiles illustrating sand and sea life in pastel hues, mostly aqua blue, and equidistantly dotted with palm trees staggered apart on each side. It almost looks like it belongs at the bottom of a pool but, with ocean levels rising, it may soon be underwater anyway.

From there, fans step across a giant baseball painted on the concrete, walk through a security checkpoint and atop a bridge over a moat (where art thou, gators?) and into a rotunda measuring 80 feet in diameter and standing some five-to-eight stories high, depending on where the angled glass roof lies. If one didn’t see the Rays logos along the walls and the baseball field painted on the flooring, some would think they’d be entering an aquarium. Though the entry was built to replicate (by size) a similar one at Ebbets Field, it doesn’t quite shout Brooklyn.

Lastly, the joint would be renamed—again—this time for a fee. Orange juice producer Tropicana forked over $1.5 million a year to put its name on the ballpark; thus it would be known as Tropicana Field through the rest of its active lifespan.

On the Catwalk.

Nearly eight years after it opened, Tropicana Field finally hosted its first baseball game. The Devil Rays took to the field on March 31, 1998, and proved five innings into their existence that the climb up the expansion ladder would be difficult, falling behind 11-0 to the visiting Detroit Tigers before pulling some late offense to make it a relatively honorable 11-6 defeat. But 45,369 fans couldn’t care less; The moment St. Petersburg had fought decades for had finally been realized.

The early years of the Devil Rays exposed a team high on aging star power with Wade Boggs, Jose Canseco, Fred McGriff, Greg Vaughn and Vinny Castilla gracing the roster. So while the team wielded spunk in the lineup, they suffered from an overmatched pitching staff with forgettable names, like one of those baseball card packs you open and want to chuck after discovering it’s full of common players.

The Yankees’ Ichiro Suzuki readies himself on the FieldTurf surface at Tropicana Field. In 2000, the facility became the first in the majors to use the artificial surface, which is less rough on ballplayers’ skin and reacts more naturally to the ball like real grass. (Flickr—Darryl Kenyon)

It didn’t take long for players and fans to discover Tropicana Field’s main foible: The catwalks. The translucent, Teflon-coated roof is held together by 24 concrete beams, themselves supported by 180 miles’ worth of cables with the help of four rings or catwalks that hang below the roof at various lengths and diameters—almost like a spiral mobile made from erector-set materials. The rings are alphabetized from A to D, from the smallest and highest (A) to the largest and closest to the ground (D). Do the rings interfere with fly balls? You bet they do, to the tune of roughly 10 a season. Which brings us to the ground rules.

If the A or B ring—or anything that either supports it or hangs from it—is struck, it’s considered a live ball on its way down. Never mind that much of the B ring hovers over foul territory; should a ball carom off it back toward fair territory, the onus is on the fielder to catch it.

On rare occasion, a pop fly will land on the A or B ring and decide to stay there. It happened to Jose Canseco during a 1999 game, with umpires declaring the play a ground-rule double—which makes no sense because the ground had nothing to do with it. Nine years later, the Rays’ Carlos Pena did the same thing, but this time the umps neglected to follow their own ground rules and called it a home run, before quickly reverting it to a double.

Sometimes a ball hitting the catwalk might bring something down with it. In 2011, the Rays’ Sean Rodriguez found something in common with Roy Hobbs when he struck one of the lights attached to the B ring in foul territory; pieces of the broken light bulb rained down near the third base coaches’ box. As grounds crews cleaned up the mess, ballpark speakers blared the theme to The Natural.

For a brief time, the A & B rings were ruled completely out of play. This took place in 2010 after the Rays lost to Minnesota in the ninth inning, as a pop fly off the bat of the Twins’ Jason Kubel made a crazy ricochet off the A ring and fell down where Tampa Bay fielders hadn’t gathered. Rays manager Joe Maddon complained loudly after the game, and MLB agreed to declare any ball hitting any of the rings to be deemed a dead ball for the postseason that followed. And then, in 2011, they forgot all about it and listed the A & B rings back in play, to the applause of fans who enjoy their pinball baseball.

The outer C & D rings have always been declared out of play, because no ball that hits them would be assumed to land within a fielder’s reach if it came to the ground unobstructed. The only exception is the portion of the rings between the foul poles in the outfield, where it’s more than assumed that a ball is well on its way to the bleachers and thus declared a home run. Initially, the ground rules saw it differently, saying that any ball hitting the C ring between the lines would be labeled a ground rule double. But just a few months into the inaugural 1998 season, that was tweaked to a home run after people found it didn’t make sense to reward a batter mashing a titanic blast off the ring with just two bases.

Beneath the occasional insanity of the catwalks, Tropicana Field plays fair for both hitters and pitchers—though at first, the Devil Rays’ woeful pitching made it seem like a bandbox when opponents batted. The field dimensions, which have not been altered in 20 years of play, are somewhat interesting; it’s a short 315 feet down the left-field line and 322 down the right, but from both corners the fence juts back 45 degrees to something a bit harder to reach.

The diagonal nook in left, in particular, is most famous for sucking in Evan Longoria’s line shot on the last day of the 2011 regular season—an extra-inning, game-winning homer that completed a remarkable September comeback for the Rays and earned them a postseason spot. The area behind the fence where Longoria’s poke landed, accessible by fans at the back end of an open picnic area, now includes a historical display entitled “162 Landing,” recalling the moment that many Rays fans consider the most memorable in franchise history.

The other quirks can be found around the 404 marker in straightaway center, especially to its left. The left-field wall, running in a straight line after making its 45-degree turn from the foul pole, begins a subtle accordion-style movement in which it bends in a little and then back to the deepest part of the yard, at 415 feet—before assuming a straight line again to a point right of center. With the exception of the nooks down each line, the walls vary from nine to 11 feet high—or, a mere spring ledge for Tampa Bay center fielder/SpiderMan impersonator Kevin Kiermaier.

On the field itself, the Trop became a trendsetter in 2000 when it became one of the first pro sports venues to install FieldTurf. Unlike the artificial fake grass before it, FieldTurf was more forgiving to the touch and more natural to the eye, with synthetic grass blades sticking out of a two-inch base mixing rubber and sand; from the stands, it looked like a giant shag carpet. Gone were the superball-like hops and carpet burns that outfielders detested, replaced with the closest thing to real grass without having to water and mow it every so often.

Tropicana Field’s main entry rotunda, with a baseball field illustrated upon its flooring, is said to be structurally similar to the one that used to welcome fans to Brooklyn’s Ebbets Field—minus the slanted glass roof. (Flickr—City of St. Pete)

Visitors in Their Own Home.

The rate of success among baseball’s expansion teams of the 1990s was surprisingly healthy. The Colorado Rockies, backed by home attendance figures that went off the charts, made the playoffs in their third season. The Arizona Diamondbacks won 100 games in their second season and a World Series in their fourth. So did the Florida Marlins, in their fifth.

The Devil Rays apparently missed the boat. They lost and continued to lose, at an average annual rate of 97 through their first 10 seasons.

The “we’re just happy to have baseball” phase lasted just one year at Tropicana Field. The Devil Rays drew 2.5 million fans in their inaugural 1998 campaign, but that figure plummeted to 1.5 million in the next year, and would be lowered even further to the point that the Devil Rays were barely scraping a million in 2002-03 as the organization made little advance in long-term evolution. It would have been worse at the gate had roughly a quarter of Tampa Bay’s home schedule not included the New York Yankees and Boston Red Sox, AL East opponents who through a combination of their popularity and Grapefruit League presence brought out an average of 40% more fans. Sure, it turned the Trop into a virtual road game for the Devil Rays as their fans seemed outnumbered by those rooting for Boston and New York, but at least it brought an invigorating climate to the ballpark—as greatly opposed to when someone like Kansas City or Seattle showed up.

When the rebranded Rays (who dropped “Devil” from the name) suddenly and shockingly catapulted to an AL pennant in 2008—and stabilized into a contender, reaching the postseason three times in the five years to follow—attendance still didn’t go through the roof. For this run of six straight winning seasons, the Rays finished 26th, 23rd, 22nd, 29th, dead last and dead last in tickets sold. When the Rays had an opportunity to clinch the AL East for the second time in 2010, only 12,446 showed up at the Trop in hopes of celebrating with the team. (The Rays lost, but clinched a day later.) Ace pitcher David Price sent out an angry response on Twitter after the game, saying the small crowd was “embarrassing.” All of this clearly underscored that losing was no longer going to cut it as an excuse.

Of course, everyone wanted to blame the ballpark. And as practically every other team settled into their nice, fancy new yard or souped up older gems, Tropicana Field remained a major league eyesore, lumped with the Oakland Coliseum as the two venues MLB desperately wanted its teams to get out of. But as easy it was to bash the Trop for being the Trop, there were other issues at work. Again, there was the distant proximity from the bulk of the Rays’ potential fan base that could shoulder the blame for the team’s poor gate. So, too, could be the non-existent presence of mass transit alternatives; besides the obligatory local bus service, there’s no light rail nor train service linking St. Petersburg to the outside world. And then there’s the fact that the Rays, despite their recent spate of winning, have never fielded a Hall-of-Fame level superstar (i.e., Bryce Harper, Alex Rodriguez) in his prime that could provide extra incentive for fans to make the drive. It’s just not going to happen with the likes of Evan Longoria or David Price, as accomplished as those players are.

The Rays have done their best to jazz up Tropicana Field’s interior, as reflected in the main concourse with pillars dressed in a touch of industry, painted murals and a king-sized player bursting through the wall. (Flickr—MarilynSJ)

Noise it Up.

The Rays tried everything under the roof to bump up attendance. Postgame concerts seemed to work in filling up the Trop, but there were only so many times the Rays could ask Trace Adkins to set up after the final out. In college football-mad Florida, one local sportswriter joked—maybe—that Tim Tebow could be hired to rake the infield dirt. (This, before Tebow actually took up baseball.) Finally, the Rays figured that to sell more seats, they had to make less of them available by throwing tarps over the upper half of the third deck. Less supply meant more demand, in theory—but demand never increased.

Away from the field, the Rays have done what they could to further make Tropicana Field come alive. In 2006, they spent $10 million into updating the fan experience, the scene-stealing element of which was the introduction of the Rays Touch Tank; it’s a 10,000-gallon pool high above the right-center field wall where cownose rays swim about. Fans can spend up to 10 minutes to touch and feed the rays, and those seated along the first three rows of the bleachers alongside the tank get a prime view of the rays swimming underwater. The pool is exposed to home run balls, as about one or two lands in the tank on average per year. “Surely PETA will be sending word to the Rays if they haven’t already,” SB Nation’s Adam Sanford once mused.

Further upgrades took place in 2014, specifically in center field where the Everglades BBQ Smokehouse, which loomed over the field through dark tinted glass as part of the batter’s eye, was replaced with The Porch in Center Field, an open-air patio catering more to Millennials who prefer to mix partying with baseball. What The Porch accomplishes is that fans can now take a full walk completely around the field within the seating bowl, and still see the action—making up for the total lack of any view from the main concourse.

Aesthetic embellishment has been taken to an almost absurd level within the Trop. The dome’s interior wall behind the bleachers, which stood naked and bland beyond belief when the facility opened in 1990, is now cluttered with ads and scoreboards of different shapes and sizes; old-timey panache is poorly attempted with two faux facades—a brick front in center field and a wrought iron replication in right. It all comes off looking like an uppity strip mall where every storefront has a different style of architecture.

The main concourse is no less overdone, from its spacious entrance to more narrow cavities as it circles around toward home plate. This is especially true on the right-field side, where the area is decked out in a festive, carnival-like atmosphere. At one point, vertical striping of blue and gold along the walls makes it look like the building’s being tented for termites.

It was hoped that Tropicana Field would initiate a positive domino effect of attracting hotels, restaurants and night life to an adjacent downtown. But even though St. Petersburg between the bay and the ballpark is a charming and relaxing place to hang, it’s not the vibrant revitalization officials had hoped for. Only one place outside the Trop has thrived as a result of it: Ferg’s Sports Bar & Grill, located across the street on the north side of the ballpark. Opened in 1992, Ferg’s has become the go-to for fans looking to get a bite and a brew before game time. The menu is quite affordable; you could get a ribeye for the same cost as a hamburger at a more posh restaurant.

Of those businesses that didn’t make the grade, one has a happy ending. The Ted Williams Museum was housed a block to the east of Tropicana Field’s main parking lot, but it struggled to get year-round attention and was forced to shutter its doors in 2006. The Rays eventually came to the rescue and gave the museum a new home inside the ballpark, locating it off the “Center Field Street” section of the concourse near the main entrance. Subtitled the Hitters Hall of Fame, the museum is more than just the Splendid Splinter, with permanent displays highlighting other great hitters; every so often, memorabilia from Cooperstown will make a guest appearance.

When the Rays win, Tropicana Field’s ceiling lights turn orange—creating a warm glow that can be seen from the outside through the Teflon-coated roof. (Flickr—City of St. Pete)

To Prop or Drop the Trop.

In 2009, Tropicana Field architect HOK Sport—now known as Populous—was asked by civic and business leaders in St. Petersburg to provide a detailed scope of how the venue could be overhauled and beautified to be more in line with modern ballparks. The firm came back with a plan to replace the roof with a retractable lid, widen the seats and concourses, and add a second level of luxury suites, among other things. Estimated price tag: $471 million. Thanks but no thanks, St. Petersburg responded.

And so, Tropicana Field structurally remains as is. Win or lose, the domed ballpark still struggles to draw crowds. Even the influx of Red Sox and Yankees fans don’t show up like they used to. The Rays are obligated to stay at Tropicana Field through 2027, a lease so resolute that the team couldn’t even look at potential new ballpark sites outside of St. Petersburg. That provision was rescinded in 2016 when the city, out of ideas to turn water into wine, allowed the Rays to start looking elsewhere. The team will likely stick around through the end of their lease, but it’s all but assured that once it’s been fulfilled, the Rays will be playing ball on the other side of the bay. Why? Because, quite simply, there’s more people there.

It’s no secret that Tropicana Field isn’t Fenway Park or Camden Yards—but it’s not Alcatraz, either. A good vibe can be derived from absorbing it in, but one has to work at it. You can’t arrive at the Trop in a bad mood and expect the ballpark to change it nine innings later.

In the end, it’s all about perspective. Remember when St. Petersburg ached for baseball over and over again, only to be denied, over and over again? Those were the bad days. Now you’ve got the ballpark and the team, even if just for a few more years. Enjoy.

Tampa Bay Rays Team History A decade-by-decade history of the Rays, the ballparks they’ve played in, and the four people who are on the franchise’s Mount Rushmore.