THE YEARLY READER

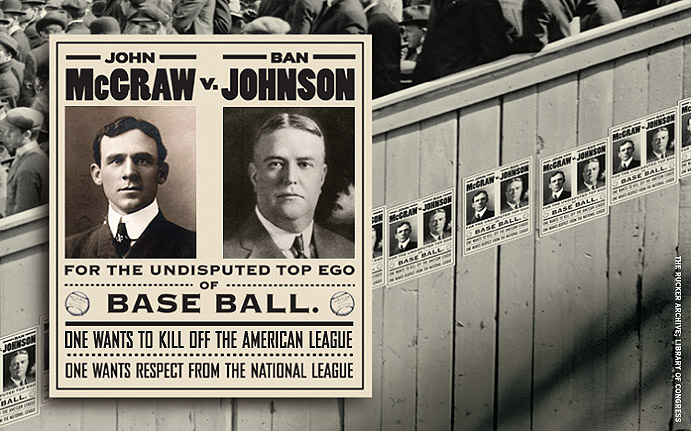

1904: McGraw v. Johnson

The intense feud between New York Giants manager John McGraw and American League president Ban Johnson reaches a destructive peak as McGraw refuses to have his National League champion Giants play a World Series against repeating AL champion Boston.

Describe a man of five feet, seven inches and weighing 155 pounds, and fear would not be the first thing to strike your mind. But few such men packed more fury than John McGraw. His diminutive structure, on close inspection, was more than compensated for with a fiery and intimidating disposition.

Ban Johnson, on the other hand, left no doubts on one’s first impression. Unlike McGraw, Johnson’s commanding presence came from a voluminous frame and booming voice.

Both of these men had, in a few short years, ascended up the last few notches of baseball’s power ladder. McGraw had taken a woeful New York Giants ballclub and quickly reinvented it as a powerhouse; Johnson had gone from major pet peeve of the baseball establishment to the most powerful man in the game.

McGraw and Johnson had crossed paths before, and they quickly realized they got along like fire and ice. Though the rest of the baseball world was now at peace, the personal war between these two men would erupt full-bore in 1904—bringing with them collateral damage that would make a victim of a second World Series.

Ever since his full-time playing days with the fabled Baltimore Orioles of the 1890s, McGraw had drawn a reputation as a bullying, ill-tempered and at times violent ballplayer. Appropriately positioned at the hot corner—third base—McGraw played as well as he harassed, batting .336 with 436 stolen bases through nine years in Baltimore. He got his first chance to manage in 1899, proving leadership abilities at age 26 that brought the Orioles to a fourth-place finish in the then 12-team National League.

But the Orioles folded after 1899, and McGraw was a man without a team to lead—until Ban Johnson came along with the American League in 1901, offering McGraw a player-manager post with an AL version of the Orioles. Not only was McGraw given a chance to steer again, he was in a way going back home.

McGraw brought all his know-how to the new league, including a vitriolic style of umpire-baiting that Johnson was trying to suppress as a selling point for the AL. When McGraw bullied the poor men in blue anyway, Johnson didn’t hesitate to respond—constantly fining and suspending the Orioles manager. His dream opportunity rapidly turning to frustration, McGraw packed up and left Baltimore midway through his second season there—stealing away many of his star players to the NL and the New York Giants.

Jumping leagues, McGraw left one mess in Baltimore and inherited another in New York. For four years, the Giants had been cellar dwelling, stumbling along with numerous managers under the detested ownership of Andrew Freedman—who, to the utter relief of many in the game, would cede control of the club to McGraw’s friend, John Brush. McGraw immediately began to retool the squad; only one everyday field player from 1902 remained a starter in 1903. Among McGraw’s new Giants were those who followed him from Baltimore: Inventive catcher Roger Bresnahan, first baseman Dan McGann and workhorse pitcher Joe McGinnity, all of whom excelled under his tutelage. McGraw also inherited one diamond in the Freedman rough: A young and extraordinarily talented pitcher named Christy Mathewson. The Giants improved by a whopping 34.5 games in 1903, bolting from last place to second.

McGraw steered the Giants into overdrive for 1904. Correctly assuming that the Pittsburgh Pirates dynasty wasn’t going away anytime soon, he continued to bulk up on talent. From Brooklyn he acquired shortstop Bill Dahlen, who would lead the NL in runs batted in—albeit with 80. And midway through the year, McGraw brought back another ex-Oriole via Cincinnati in “Turkey” Mike Donlin, who would finish the year batting .329.

But pitching was the Giants’ undeniable strength.

McGraw had a spectacular duo in McGinnity and Mathewson. The 33-year-old McGinnity, who McGraw hoarded wherever he went, won 35 games against just eight losses, completing 38 of 44 starts and posting a league-leading 1.61 earned run average. Mathewson, paling only slightly by comparison, finished 33-12 with a 2.03 ERA, and led the NL with 217 strikeouts. Together, McGinnity and Mathewson’s 68 wins are the most by a pitching duo in baseball’s modern (post-1900) era.

BTW: McGinnity won his first 14 decisions of the year before losing a 12-inning, 1-0 game against Chicago before a Polo Grounds crowd of 38,805—the largest in major league history at the time.

What little action was left for the remainder of the Giants’ pitching staff was well taken advantage of. Luther “Dummy” Taylor could neither hear nor talk, but he was no dummy on the mound, winning 21 games; rookie Hooks Wiltse won his first 12 decisions to set a major league mark that still stands, on his way to a 13-3 record.

BTW: Taylor’s teammates learned signed language to help overcome his handicap on the field.

Though McGraw was highly respectful of his players—he believed that anyone who could perform under his tough, disciplined work ethic deserved respect—he could breathe fire in an instant. If he felt any of his players wasn’t executing to his expectations, they would feel the white-hot wrath of McGraw’s icy stare, if not worse. His miniature shape and iron-fisted disposition helped earn him a spirited nickname: Little Napoleon.

Occasionally, McGraw’s aggressive, sometimes combative influence got out of hand. During a spring training game in Mobile, Alabama, an umpire was beat unconscious after angry Giants players ganged up on him (The team quickly split town before authorities could arrest them); in a regular season game at Cincinnati, catcher Frank Bowerman went charging after a fan in the stands. Giants fans at the Polo Grounds also appeared to ride with McGraw’s emotions, and McGraw himself nearly paid for it one day after a doubleheader win, as raucous fans swarmed upon the field and stampeded over him; he suffered ankle injuries as a result. Nevertheless, McGraw never felt more at home then being back in the NL, where the heckling and rowdyism remained a tolerated part of the game.

The Giants swarmed all over NL opponents, racking up a 106-47 mark to finish 13 games ahead of the second-place Chicago Cubs. The Pirates, three-time defending NL champions, slipped to fourth as injuries and the continued depletion of their once-talented pitching staff took their toll.

Ban Johnson’s revenge on McGraw and Brush for attempting to kill off the Baltimore Orioles in 1902 began in 1903, when he moved the Orioles to New York and made them hostile neighbors with the Giants. As the AL’s supreme power broker, Johnson engineered trades and acquisitions that made his new Gotham entry, the New York Highlanders, more competitive. After a last-place showing at Baltimore in 1902, the Highlanders hopped to fourth in 1903, 10 games over the .500 mark.

Relievers are for the Medicine Cabinet

At a time when starting pitchers were expected to go the distance, the Boston Americans came within one relief appearance of setting the all-time modern record for the fewest in one year. That record was tied in 1904 by the Cardinals; the list of runners-up all played between 1900-04.

Two decades before the name Harry Frazee became damned in the hearts and minds of Bostonians, fans of the defending AL champion Boston Americans would spend much of 1904 cursing the name of Ban Johnson for a similar series of imbalanced trades that ultimately hurt their team—and greatly helped the New York Highlanders.

First there was a preseason trade in which Long Tom Hughes, a breakout 20-7 pitcher at Boston, was shipped to New York for 15-15 hurler Jesse Tannehill. If Johnson’s aim was to strengthen the Highlanders at Boston’s expense, it backfired. Tannehill joined Cy Young and Bill Dinneen to form a trio of 20-game winners at Boston, while Hughes struggled to a 7-11 start. So back to work Johnson went, sending Hughes to low-grade Washington in exchange for veteran Al Orth—who would fare better in New York, producing an 11-6 record and 2.68 ERA after going 3-4 with a 4.76 figure with the Senators. But in June, Boston fans were sent over the top in their outrage when Patsy Dougherty—a popular outfielder and very effective leadoff hitter—was traded one-up to the Highlanders for a benchwarmer named Bob Unglaub. Dougherty would bat .283 and score 80 runs in his 106 games at New York, while Unglaub would poke out a mere two hits in 13 at-bats at Boston.

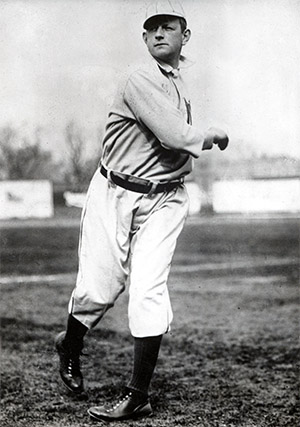

“Happy Jack” Chesbro was exhaustingly happy with his 1904 numbers, which included 41 wins pitched over 454 innings. (The Rucker Archive)

The 30-year-old ex-Pirate had won 21 games for New York the year before, but in 1904 he exploded with a Herculean effort. The individual numbers were staggering: 41 victories (against 12 losses), 454 innings pitched and 48 complete games. His ERA through all the labor came in at 1.82, fifth in the AL.

The two teams were all but knotted together, trading first place with one another as the season wound down into October. The Highlanders had survived a three-week road trip in which they won 13 of 21; Chesbro was the victor in seven of those. But they trailed Boston by half a game, with five left—all against the Americans.

Regardless of who won the American League pennant, both the Highlanders and Americans had agreed that the champions would once again challenge the NL victors—long since determined to be the New York Giants—to a second World Series. The call went out to the office of Giants owner John Brush. But he wouldn’t have it.

Ironman Jack

While managers today cross their fingers when a starting pitcher goes to the mound on less than four days’ rest, it may serve them to note that Jack Chesbro made only 11 of his 51 starts in 1904 with four or more days off in between. In fact, as the chart below shows, the majority of starts by the New York Highlanders’ ace over the final two-plus months were on two days’ rest or less.

Loathing the possibility that he would play a World Series against the very team he and McGraw once tried to ruin—and now felt was infiltrating their territory—Brush publicly refused any request to play any AL winner, stating that the Giants were not interested in playing anyone from a “minor league,” and that they were “content to rest upon their laurels.” Both the fans and the press protested.

On the eve of a Boston-New York series that would determine the AL pennant, McGraw stepped forward and claimed responsibility for the decision not to play. The irascible manager, not wanting any association—direct or indirect—with Ban Johnson, declared that winning the NL flag was the highest honor in baseball, and he was not willing to “see it tossed away like a rag.”

NL President Harry Pulliam not so much backed the Giants’ position as he was powerless to do anything about it. He emphasized that there was no contractual obligation for the league champions to meet in any postseason event.

Fan interest in both Boston and New York was intense for the AL-deciding series. The Royal Rooters, the Americans’ rabid batch of band-playing fans, made the trip to New York for the first game and declared their seats behind the Boston dugout. But any noise they were going to make was quickly silenced by Chesbro, who edged Boston, 3-2. Highlanders fans carried “Happy Jack” off the field in celebration.

While the New York Giants played out a listless string after taking the National League flag, the American League race remained hot to the finish as the New York Highlanders and Boston Americans proved with this crucial doubleheader at Boston on October 8. (Library of Congress)

A doubleheader in Boston the next day saw the momentum turn in favor of the Americans. Less than 24 hours after winning at New York, Chesbro was again sent out by New York manager Clark Griffith to start. The effects of having no rest were obvious as Chesbro’s superhuman limits were reached, allowing six runs in the fourth innings before being relieved in a 13-2 Boston rout. Cy Young then outpitched Jack Powell, 1-0, in the second game to give the Americans a 1.5-game lead—with a final doubleheader slated two days later back in New York.

Chesbro was once again given the call for his sixth start in 11 days. A crowd of 28,000 loaded up Hilltop Park—capacity, 16,000—and Happy Jack was back in apparent form, shutting down the Boston bats. When Chesbro came up to hit in the third, Highlanders fans stopped the game to shower him with lavish gifts, including a sealskin coat. Chesbro said thanks, went back to work and hammered out a triple. Unfortunately, his team couldn’t bring him home.

Ahead 2-0 in the seventh, Chesbro’s teammates let him down again when two unearned runs crossed the plate for Boston to tie the game, and it stayed even until the ninth.

Boston catcher Lou Criger led off with a single. A sacrifice bunt and ground out ensued, moving Criger to third base with two outs. Freddy Parent came to the plate, and with the count at 2-1, Chesbro fired away with a legal spitball; it sailed high over the reach of catcher Red Kleinow and to the backstop. Criger scored easily from third, and Boston shut down New York in the bottom of the ninth to clinch the AL pennant.

Most everyone went home, not bothering to see a meaningless second game won by New York, 1-0. Chesbro had all but single-handedly brought his team to the brink of an AL championship, but it seemed fans and historians would remember him instead for the wild pitch that cost it for the New York Highlanders.

The euphoria that surrounded the end of the AL regular season had the true look and feel of postseason competition, and it made for a rousing finish to the fourth campaign of Ban Johnson’s league. Meanwhile across town, any celebration at the Polo Grounds had long since subsided and turned to indifference, and then disorder. After the Giants clinched the NL pennant with their 100th win on September 22, they played out the string as if they could care less—as did what few fans showed up at the Polo Grounds, resorting to misbehavior and nearly causing a riot during the season’s final game.

BTW: The Giants were 6-10 after clinching the NL pennant; all but one of those games were played at home.

John Brush saw the lingering, deadening effects of a season long since decided in front of him, at the same time well aware of the enthusiasm taking place at Hilltop Park. He was hearing it from the press, which was burying him with criticism over his team’s decision not to play Boston.

It didn’t take Brush long to come around. Ninety years would pass before fans would be robbed of another postseason.

Forward to 1905: The Zero Heroes Christy Mathewson and Joe McGinnity completely deny the Philadelphia Athletics in the World Series.

Forward to 1905: The Zero Heroes Christy Mathewson and Joe McGinnity completely deny the Philadelphia Athletics in the World Series.

Back to 1903: The First World Series With peace at hand, the American and National Leagues join hands in October and stage the first Fall Classic.

Back to 1903: The First World Series With peace at hand, the American and National Leagues join hands in October and stage the first Fall Classic.

1904 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1904 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

1904 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1904 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

The 1900s: Birth of the Modern Age The established National League and upstart American League battle it out, then make peace to signal in a new and lasting era.

The 1900s: Birth of the Modern Age The established National League and upstart American League battle it out, then make peace to signal in a new and lasting era.