THE YEARLY READER

1905: The Zero Heroes

Christy Mathewson and Joe McGinnity completely deny the Philadelphia Athletics in the World Series for the New York Giants.

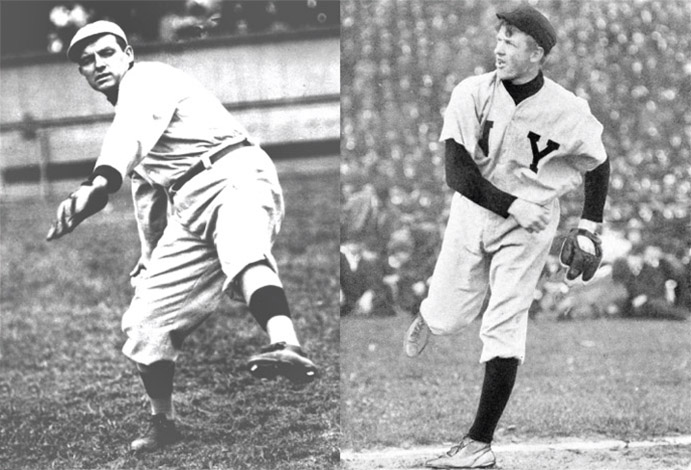

Joe McGinnity (left) and Christy Mathewson became a virtual two-man pitching staff for the New York Giants in a dominant World Series Series triumph. (The Rucker Archive)

In 1904, the New York Giants’ spiteful arrogance shut the American League out of the World Series.

A year later, the Giants’ stunning display of pitching would shut out the junior circuit at the World Series.

From the dugout to the front office, the National League champions were as mean and malcontented as ever, continuing to use every dirty trick in the book while the rest of baseball was cleaning up its act. But after absorbing a public pounding for their refusal to play the 1904 World Series—resulting in a rare case of self-pity—the Giants decided it was a better thing to prove their worth as baseball’s best team rather than to venomously brag about it.

Prove it they would in 1905. After a thunderous romp through the regular season, the Giants paired up with the Philadelphia Athletics and knocked the AL champions down flat with, undoubtedly, the greatest exhibition of pitching ever witnessed in a World Series.

The year began with Giants owner John Brush and his testy, pesky manager John McGraw doing damage control for their World Series balk, done out of spite for Ban Johnson—the AL czar they so blatantly hated. Making up, Brush personally helped write up the rules for the modern World Series, in the process finally snuffing out whatever hot spots remained in the otherwise doused AL-NL inferno. Fans were now assured that the two leagues would advance their best into October to determine, without argument, the true champion of major league baseball.

Brush may have had further incentive for assuring the World Series, idealizing the extra income his franchise and players could accrue with an extra series of sold-out affairs. That is, of course, if the Giants made it.

Which, predictably, they would.

If any team was more modeled after the personality of the baiting, brawling McGraw, the 1905 Giants was it. McGraw would ultimately manage 33 years, winning 10 pennants and three World Series titles, but he would fondly recall the 1905 edition as the best he ever led. And not just because they won, won and won again; it was because they fought, fought and fought again.

Headlining the Giants’ star antagonists was center fielder “Turkey” Mike Donlin, a talented if unpredictable sort who managed to play everyday in 1905 and place third in NL hitting at .356. In previous years, Donlin had occasionally wandered off to perform Vaudeville and led there in hitting, too—as recalled with a young actress who Donlin once slugged outside a Baltimore theater.

Ironically, no Giant punched out more opponents—legally, from the pitching mound—than the team’s least pugnacious player: Christy Mathewson.

While most ballplayers were escaping coal mines and back alleys, there was the 24-year-old Mathewson: A congenial, well-groomed, blue-eyed former class president of Bucknell University. But Mathewson’s upbringing wasn’t all that made him stand out from other major leaguers; he had also become baseball’s most unsolvable pitcher. Patient, intelligent and armed with a screwball that certainly screwed with the minds of opposing hitters, Mathewson won over 30 games for the third straight year, threw his first career no-hitter against Mordecai “Three Finger” Brown and the Chicago Cubs, and earned the first of five career earned run average titles at 1.28.

BTW: Mathewson’s no-hitter would be the last laugh he would have over Brown for quite a while, losing his next nine decisions against the future Hall-of-Famer.

But even Mathewson, clean-cut image and all, couldn’t refrain from being a party to the schoolyard bully ethic for which the Giants played to perfection. When a very young lemonade vendor mercilessly heckled him during a game at Philadelphia, Mathewson staggered the kid with a blow to the mouth. Such was the effect John McGraw had on this team.

As always, the 32-year-old McGraw led by example—and in 1905, he was in top form. Umpires booted him out of 13 different games. He made a reporter pay for asking a loaded question by grabbing the man’s nose and twisting it. And McGraw ignited the year’s biggest controversy when, shortly after being ejected in a game against Pittsburgh, he returned and engaged Pirates owner Barney Dreyfuss in a shouting match that started with “Hey Barney!” and ended with him needling Dreyfuss with accusations of gambling and controlling umpires. A furious Dreyfuss successfully lobbied the NL to suspend McGraw 15 games for the outburst, but it got shortened when John Brush got a court injunction against the NL ruling—which they noted was handed down by league president Henry Pulliam, a former Pirates executive under Dreyfuss.

BTW: Barney Dreyfuss would never live down the incident; for years, Giants fans would harass him whenever he visited New York with cries of “Hey Barney!”

The Pirates were no less frustrated by the Giants than their boss was. The Bucs started slow and it cost them; they quickly and fatally handicapped themselves to an 8.5-game deficit to end May, never to make it back up. Winning their second straight NL pennant, the Giants led in practically all major offensive categories, held the league’s second lowest ERA (at 2.39), struck out more batters and walked the fewest.

The Giants found a truly opposite number in the American League: The Philadelphia Athletics. The A’s were the anti-Giants, managed by the anti-McGraw, headlined by the anti-Mathewson.

Quiet and businesslike, the A’s were run by Connie Mack, who diametrically differed from McGraw as a tall, calm presence in a three-piece suit. Mack’s attitude seeped into his players, who went about their business and delivered steady and constant results minus the mean spirit. Every starting regular hit between .262 and .284, the latter number achieved by first baseman Harry Davis, perhaps the most gentlemanly of the A’s. The same could not be said for his offensive game, which harassed opponents with AL highs in 47 doubles, eight home runs, 83 runs knocked in and 92 scored.

Philadelphia’s starting rotation was also well balanced, with ever-consistent Eddie Plank (a 24-12 record, 2.26 ERA), 22-year-old rookie Andy Coakley (18-8, 1.84) and, in his third year, 21-year-old Chief Bender (18-11, 2.83), who was half-Native American. And then there was the ace of the A’s: Rube Waddell.

On the mound, Waddell was everything Christy Mathewson was—leading the AL in wins (27, against 10 losses), ERA (1.48) and strikeouts (287). But unlike Mathewson, Waddell didn’t rely on the screwball; he was a screwball. While Mathewson was spending the off-season engaged, likely, in high societal dining with old Bucknell friends, Waddell was spending it throwing flatirons at his in-laws and then escaping town to evade authorities. Waddell’s eccentric belligerence had estranged every previous manager he played for, and although Connie Mack had always viewed him as a difficult pet project, the A’s manager became the one person patient enough to know when to give the southpaw slack and when to rein the leash back in again.

Much of the AL season’s first few months belonged to the Cleveland Naps, renamed in honor of fourth-year Clevelander and first-year manager Nap Lajoie. But Lajoie developed blood poisoning from a serious spike wound on June 30 that also poisoned his team’s pennant hopes. Lajoie’s season-ending injury plummeted the Naps from a first-place, 36-21 mark to a below-.500 finish.

The Chicago White Sox, armed with a starting rotation every bit the equal of the Athletics’, took over first and spent much of the summer fighting off Philadelphia, but ultimately lost the battle to Mack’s more multi-faceted team. Waddell was the hero on the mound, pitching 44 straight innings of shutout ball late in the year to help override the White Sox in the standings. Harry Davis, meanwhile, provided the heroics at the plate and finished Chicago off with the year’s most memorable hit on September 28. Against the White Sox at Philadelphia, Davis singled into the outfield and the ball changed direction when it struck the glove of teammate Topsy Hartsel. It was all perfectly legal in a time when players left their mitts on the field while at bat, and the topsy-turvy turnabout allowed Topsy, on second, to gain an extra base on the play and score the winning run in a game that helped Philadelphia sew up the AL pennant.

Throughout the late season, the lure of a Giants-A’s World Series had been largely built on the dream pitching duel of Christy Mathewson and Rube Waddell. Alas, it would remain a dream.

While traveling by train with his teammates in early September, Waddell decided he didn’t like Andy Coakley’s straw hat and wrestled with the rookie pitcher to get it off him. In the process Waddell damaged his pitching shoulder, and though he threw in a few games afterward, he was pained, ineffective and ultimately done for the year. He would miss the World Series entirely.

BTW: Rumor had it that Waddell intentionally hurt himself to appease gamblers who paid him $17,000 to stay out of the World Series. Most believe the story to be without merit.

And, so it seemed, did the Philadelphia offense.

Though only 24, Christy Mathewson had long since established himself as one of baseball’s great pitchers when he took the mound for Game One. But over the next week, he would elevate his status to that of a living legend.

At Philadelphia, Mathewson blanked the A’s on four hits to start the World Series. In Game Three, Mathewson returned on two days’ rest and performed his idea of the status quo: Another four-hit shutout. And then in Game Five—on one day’s rest—the Giant ace gave in a little. He gave up six hits. The A’s still couldn’t score.

Thirst for Thirty

Only five pitchers since 1900 have won 30 or more games in consecutive seasons. Two of them—Christy Mathewson and Joe McGinnity—did it together for the New York Giants from 1903-04.

Mathewson’s esteemed partner in the Giants rotation, Joe McGinnity, had spent much of 1905 showing signs of exhaustion after six years of efficiently eating up innings like a lumberjack devouring pancakes. His production slowed and his ERA rose, but he still won 21 games. McGinnity showed, in the one World Series he would ever play in, that he had plenty of gas left in his tank—though his luck didn’t allow the scoreless perfection afforded to Mathewson.

McGinnity started Game Two and scattered six hits through eight innings—but the Giants defense failed him, committing two errors that led to three unearned runs. Worse, opposing A’s starter Chief Bender performed his own imitation of Mathewson and shut the Giants down on four hits. But back came McGinnity on two days’ rest for Game Four and, this time without any glitches from his fielders, got the shutout he deserved—blanking the A’s on five hits.

Healthy or injured, bribed or not, Rube Waddell wouldn’t have made a difference for the Philadelphia Athletics in the World Series. God Almighty wouldn’t have made a difference. Mathewson and McGinnity were simply too infallible. In five games over six days, the two Giant aces hurled 44 innings and didn’t allow a single earned run, as the A’s could only manage a .152 average and four walks against them.) Only one other inning was thrown by a Giant not named Mathewson or McGinnity; Red Ames, a 22-game winner during the year, pitched the final frame of Game Two because the Giants were desperate for a rally in the inning before and pinch-hit for McGinnity. All totaled, the Giants’ 0.00 team ERA in their five-game triumph over the A’s is a World Series record that can never be erased from the record books.

A year before, the Giants turned their backs on the American League and staked their claim as world champions, even as the outside majority opinion shook its fists at them. But the celebration of 1905 would be anything but bittersweet. Playing to prove their worth as the best, the Giants left almost as many doubts as earned runs scored against them at the World Series: Zero.

Forward to 1906: The Hitless Wonders How the Chicago White Sox bat .230 with seven home runs all year—and still become world champions.

Forward to 1906: The Hitless Wonders How the Chicago White Sox bat .230 with seven home runs all year—and still become world champions.

Back to 1904: McGraw v. Johnson The World Series becomes a casualty of a continued feud between two of the games’s most powerful men.

Back to 1904: McGraw v. Johnson The World Series becomes a casualty of a continued feud between two of the games’s most powerful men.

1905 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1905 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

1905 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1905 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

The 1900s: Birth of the Modern Age The established National League and upstart American League battle it out, then make peace to signal in a new and lasting era.

The 1900s: Birth of the Modern Age The established National League and upstart American League battle it out, then make peace to signal in a new and lasting era.