THE YEARLY READER

1919: Say it Ain’t So

The Chicago White Sox lose a best-of-nine World Series to Cincinnati under suspicious circumstances, as rumors fly of gamblers bribing crucial Sox players to throw the games. It’s the nadir of an ugly year in which game-fixing gossip runs rampant.

A team picture of the infamous 1919 Chicago White Sox, with the eight players involved in fixing that year’s World Series circled.

In the first game of the 1919 World Series, Eddie Cicotte of the Chicago White Sox went to the mound and promptly hit the first batter he faced, Cincinnati’s Morrie Rath, square in the back.

Too much adrenaline, most in the crowd thought, or perhaps a case of butterflies.

But for others more decidedly and deviously in the know, the 35-year old’s first delivery was deadly accurate.

It was a signal that the World Series was on its way to being fixed.

For years the public had heard rumors of bribery and game fixing in baseball, but tended to think nothing of it. The general consensus was that the game was played to the highest level of righteousness. Fans held the faith that it was inconceivable for players to be corrupted, for games to be thrown.

Yet within baseball’s inner circle, the rumors became more substantive. Owners had often suspected games might be fixed, but there was little they wanted to do about it, since it risked exposing the facts and generating bad publicity among the public. As long as the crooked play didn’t get out of hand, the owners would keep a lid on it.

But the 1919 World Series—purposely squandered by eight White Sox ballplayers—was too big a bomb to muffle, exploding apart any attempts at suppression. It would turn the game of baseball completely upside down, cause a generation of Americans to gasp in shock, and scramble panicked owners into finding instant, face-saving solutions.

The White Sox continued to be one of baseball’s best nines, but owner Charles Comiskey paid them as if they were the worst. Eddie Collins was the highest paid player at $12,000; salaries went spiraling down from there. Joe Jackson, an established superstar, received half of what Collins was paid. The other players within the White Sox’ highly talented roster made even less.

To add insult to financial injustice, Comiskey made his players pay to keep their uniforms clean. In protest, the players rarely did. For this they earned the name “Black Sox.”

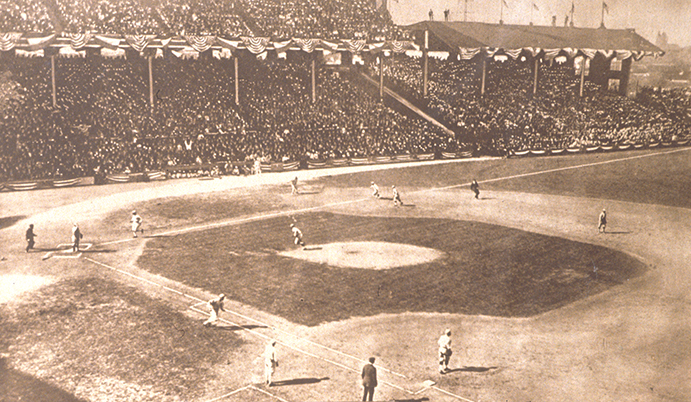

Comiskey’s pettiness seemed increasingly unjustified. After a war-torn off year in 1918, the White Sox reverted to their 1917 championship form on the field and at the gate in 1919. The players looked sharp and regained first place; home attendance tripled. Comiskey, like other baseball owners, had buckled up for what he thought would be a slow return of fans in 1919—only to discover an America ready to party in the Great War’s victorious aftermath, with spectators flocking to ballparks everywhere.

BTW: Overall, major league attendance doubled from 1918 and set a per-game attendance record in 1919.

The Urban Legend of Eddie Cicotte

Many historians believe that the fuel that fed Eddie Cicotte’s anger into helping fix the World Series came after he failed to win 30 games—and thus failed to earn a promised $10,000 bonus—because he allegedly was held back in the waning weeks on orders from White Sox owner Charles Comiskey. Some say this happened in 1917, when Cicotte won 28 games; others claim it took place in 1919—when he won 29. In either case, it appears to be a case of the truth being stretched. In 1917, Cicotte was given two starts in the season’s final week and won them both—dismantling any thought that he was being forced to rest then. Two years later, Cicotte was removed from his last start after two innings with a 2-1 lead; under the rules of the day, Cicotte would have been credited with his 30th win had the White Sox stayed in front, but they lost, 10-9. Still, Cicotte by then had already committed to the fix, so where was the motivation to stick it to Comiskey if he still had a chance at collecting the $10,000 bonus? (Photo: The Rucker Archive)

Knowing their trifling salaries had been set in the unfounded fear that seats wouldn’t be filled, White Sox players grew more and more restless throughout the season. At one point they nearly went on strike for more money, but were cajoled back on the field when new manager Kid Gleason, relaying a message from Comiskey, told the players they’d be promised a special bonus.

The players had heard that one before. Broken or weak promises from Comiskey had become something of a ritual, and the players were tiring of the routine.

Though they all hated Comiskey, the White Sox players had just as hard a time getting along with one another. Two factions had arisen from the ranks; one group had developed an incensed jealousy for the well-paid Collins, and made up the cabal of players that would conspire to throw the World Series.

Yet through all of the distractions, the White Sox continued to play sparkling baseball. They held first place for the season’s final three months, easily withstanding challenges from the New York Yankees and the Cleveland Indians.

BTW: The defending champion Boston Red Sox dropped to sixth place thanks to a collapsed pitching staff—and despite a record-breaking 29 home runs from Babe Ruth. Little did anyone realize he was just warming up.

Chicago looked primed for its second World Series victory in three years. Jackson batted .351; Collins added a .319 average and led the AL in steals. Buck Weaver, Chick Gandil, outfielder Nemo Liebold and utility infielder Fred McMullin all batted at or near .300. The pitching staff was highlighted by Eddie Cicotte, who for the second time in three years flirted with 30 wins; his 29-7 record and .806 winning percentage were league bests. Lefty Williams, at 26, surpassed 20 victories for the first time with a 23-11 mark; rookie Dickie Kerr added a 13-8 record to the rotation.

With the White Sox in Boston two weeks before the end of the season—and the team’s clinching of the AL a mere formality—Chick Gandil made the first move to set a fix in motion. He met up with Joseph “Sport” Sullivan, a bookmaker and gambler, and claimed that for $80,000 he could fix the World Series. Sullivan would view the payment as an investment; with inside knowledge of who would win, he could assuredly bet all the money he had on the underdog.

Gandil immediately set out to ring in as many players as he could to go in on the fix. Cicotte, though initially uneasy about the idea, felt he had been shafted by Comiskey long enough. He was in.

Lefty Williams was even more hesitant, agreeing only when he heard Cicotte was in.

With the two best pitchers in the rotation involved, Gandil had no problem getting Jackson, Felsch and Weaver—the middle of the batting order—into place. Shortstop Swede Risberg, Gandil’s pal, was a cinch to participate.

Gandil had no choice but to include Fred McMullin when the bench player eavesdropped on Gandil and Risberg.

Meanwhile, the plot on the gamblers’ side thickened. When the White Sox moved on to New York, Cicotte was overheard discussing the plan from Bill Burns, a former pitcher with brief and mediocre major league experience. After pressing Cicotte, Burns wired a friend—an ex-fighter named Billy Maharg—back in Philadelphia. Burns and Maharg then sought out Arnold Rothstein, a young, high-ranking and well-connected gambler in New York City.

BTW: Billy Maharg’s past life as a major leaguer was even briefer than Burns, playing in two games—one as a replacement Detroit Tiger in the infamous 1912 affair boycotted by the real Tigers over a suspended Ty Cobb.

Rothstein grudgingly listened in on Burns’ and Maharg’s request to bankroll a fix, but decided he didn’t want any part of it. But soon after he got another call—from Sport Sullivan, making the same request. This time Rothstein listened, since Sullivan was of considerable more standing than relative two-bit players like Burns and Maharg.

At the same time, Burns and Maharg had heard back from Rothstein’s go-between—Abe Attell, another ex-fighter of suspect character—and were told that Rothstein was ready to finance the fix for them. Little did they know Attell was making the story up.

Initially, the White Sox were heavy favorites to win the World Series, even though their opponents—the Cincinnati Reds—had a much stronger record in clinching their first-ever National League pennant. Under new manager Pat Moran—who tired of toiling under the reign of another frugal owner, the Phillies’ William Baker—the Reds were remarkably reliable and consistent without overpowering anyone. Yet their 96 wins—in a shortened 140-game schedule—made up the NL’s best record by the percentages in 10 years.

BTW: As he did with the Phillies, Moran took the Reds to the NL pennant in his first year guiding them.

As the two teams readied to start the best-of-nine World Series in Cincinnati, the eight Chicago players waited for $40,000 they had agreed to receive up front from Rothstein, via Sullivan. They got only $10,000; in a fit of greed, Sullivan bet the other $30,000 on Game One. Cicotte, the Game One starter, was given the advance cash since he was adamant about receiving it. Meanwhile, the money Burns and Maharg thought they were getting from Rothstein—via Attell—was not coming. They were told to sit and be patient.

BTW: Looking for ways to gain extra revenue after World War I, owners expanded the World Series from a best-of-seven to a best-of-nine, a format that would last through 1921.

Most of the conspiring Sox started to suffer cold feet as the Series began. Jackson reportedly begged manager Gleason not to play him; Gandil was hesitant at the lack of promised money; and Buck Weaver decided to back out entirely, though he kept his knowledge of the fix a secret—a move that would haunt him through to his dying days.

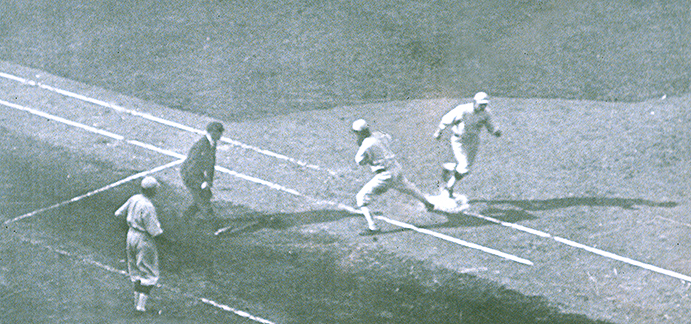

Game One: The White Sox’ Chick Gandil is charged with an error for dropping a throw from Buck Weaver, allowing the Reds’ Edd Roush to reach base safely. Two runs, one unearned, score in the seventh inning of a 9-1 Cincinnati win. (The Rucker Archive)

Cicotte helped the White Sox lose Game One when he allowed five fourth-inning runs—all scored after two were out. He kept the inning alive when he intentionally hesitated making a throw to second on what should have been a double play.

Williams lost Game Two; though he gave up only four hits over eight innings, they came in convenient bunches to allow the Reds to pile up four runs.

The Black Sox hitters had done their jobs as well, contributing to Chicago’s meager total of three runs in the first two games.

Comiskey was growing suspicious, but he didn’t know who to talk to. He couldn’t talk to Garry Herrmann, head of the National Commission; he owned the Reds. He wouldn’t talk to AL President Ban Johnson; their once-close friendship had long since disintegrated. That left him with NL President John Heydler, who replied back, “You can’t fix a World Series, Commy.” Heydler nevertheless took Comiskey’s concerns to Johnson, who vindictively accused Comiskey of crying foul to cover up his team’s poor performance.

Comiskey wasn’t alone. White Sox Manager Kid Gleason was also leery, then angry, confronting the suspect players—and nearly coming to blows with Gandil after Game Two.

Game Three: With none of the promised bribe money coming in, the Black Sox begin playing on the up and up. Below, Chick Gandil delivers the decisive blow of the game, a two-run single that scores Joe Jackson and Happy Felsch in a 3-0 win. (The Rucker Archive)

Gandil still hadn’t received his promised cash from Sullivan, and nothing from Burns and Maharg. After the White Sox won Game Three on a shutout by Dickie Kerr—who was not in on the fix—Gandil warned the gamblers that unless he started to get the money, the deal was off. Sullivan responded by giving him $20,000; Burns and Maharg continued their patience, waiting for money from Attell that he never had in the first place.

Cicotte and Williams started and lost Games Four and Five. They didn’t have to look terrible; the Black Sox hitters were taking care of that (as were their untainted teammates), going scoreless in both games. Still, the only two runs Cicotte allowed in his loss were unearned—thanks to errors he created himself.

Faced with the unenviable task of winning four straight if they really wanted to win the Series, the White Sox—all of them—began to try. Not only wasn’t the money coming in, the conspiring gamblers had vanished as well.

After winning the next two games—the second of which with Cicotte pitching—the rejuvenated players finally received a visitor. Game Eight starter Williams was accosted by a stranger of intimidating presence who warned that he could either lose the game—or lose wife.

The Mafioso tactic scared the 26-year old straight into line. Williams quickly allowed four runs in the first inning before Gleason pulled him. The Reds coasted to a 10-5 win and clinched the Series.

The performance of the Black Sox was indeed awful as planned, but there was one eye-opener. If Joe Jackson wasn’t playing to the best of his ability, it’s inspiring to think what he might had done if he had; he hit the best of any player on either team, batting .375 while hitting the Series’ only home run. The rest of the Black Sox—the self-exonerated Buck Weaver omitted—hit .167.

Black Sox vs. White Sox

When breaking down the combined batting numbers of the seven conspiring Black Sox participants (not including Buck Weaver) and comparing them with the “clean” White Sox players, it’s hard to find damning evidence. But in terms of fielding and pitching, the smoking guns emerge.

As the World Series ended and winter approached, rumors buzzed regarding a possible White Sox fix, but they died like every rumor before it. But there was a stubborn mule in the pack. Chicago sportswriter Hugh Fullerton had heard and seen enough circumstantial evidence to suggest to him there was more fact than fiction to the story. He wrote a series of articles that attempted to drum up attention to the matter, even stating in one article that seven players would not be back for the White Sox in 1920. No one seemed to believe Fullerton; baseball periodicals of the day especially raked him over the coals in public with vicious editorial responses.

Everyone seemed convinced that baseball was above being fixed.

Everyone was in for a shock.

Forward to 1920: Saviors of the Game Babe Ruth and Kenesaw Mountain Landis restore excitement and credibility to an ailing game.

Forward to 1920: Saviors of the Game Babe Ruth and Kenesaw Mountain Landis restore excitement and credibility to an ailing game.

Back to 1918: All Work or Fight and No Play Baseball scratches and claws to stay intact as World War I reaches its brutal apex.

Back to 1918: All Work or Fight and No Play Baseball scratches and claws to stay intact as World War I reaches its brutal apex.

1919 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1919 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

1919 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1919 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

The 1910s: The Feds, the Fight and the Fix The majors suffer growing pains as they deal with a fledgling third league, increased scandal and gambling problems, and a brief interruption from the Great War.

The 1910s: The Feds, the Fight and the Fix The majors suffer growing pains as they deal with a fledgling third league, increased scandal and gambling problems, and a brief interruption from the Great War.