THE YEARLY READER

1924: A Couple Bad Hops Better

A tightly contested World Series climaxes when an 18-year-old rookie watches two ground balls hop wildly over his head in the seventh game, resulting in the Washington Senators’ first, last and only championship.

Any student of baseball’s record books would read John McGraw’s first 21 years as the New York Giants’ manager like a chronicle of success to be proud of: 20 first division finishes, nine National League pennants and three world championships.

But hidden within the numbers are the many heartbreaks McGraw suffered and the fashion in which they happened: Fred Merkle not touching second base in 1908, costing the Giants a pennant; the missed pop flies in Game Seven of the 1912 World Series that handed victory to the Boston Red Sox; the botched rundown five years later, with Heinie Zimmerman desperately chasing the Chicago White Sox’ Eddie Collins home with no one to throw to, depriving them of another championship.

In 1924, McGraw and the Giants made it 10 pennants in 23 years. But yet again, another fateful date of snakebit frustration awaited them at the Fall Classic.

Meanwhile, the Giants’ World Series opponents—the Washington Senators—were just happy to finally be there.

The first quarter-century of the Senators’ existence was unkind in different ways. They spent their first decade mired in or near the American League cellar, then made significant headway in the 1910s with the addition of a headstrong manager in Clark Griffith and, more importantly, the arrival of legendary pitcher Walter Johnson. The team went from pretender to contender solely on the success of Johnson’s flame-throwing arm, but they never could reach higher than second place in the AL standings.

Johnson was one of the game’s nicest guys, but he threw its meanest fastball. Many today still believe no one threw as hard or as fast; when Ray Chapman once fell behind two strikes at the plate thanks to a double dose of Johnson’s wicked heat, Chapman conceded the at-bat and walked back to the dugout before Johnson could finish him off.

In 1920, just when the Senators began building some punch at the plate to back up Johnson, the Big Train derailed. He developed arm trouble, and from 1920-23 his collective record was a plain 57-52. The team followed suit and failed to make a dent in the pennant race.

No one had expected the Senators to burst out in 1924. Certainly not the New York Yankees, who looked too dominant not to repeat as AL champs. Probably not Clark Griffith, who now as Washington’s owner was busy installing his fourth manager in four years—first-time skipper Bucky Harris, the Senators’ 27-year-old second baseman. Most importantly, few felt much was left in the 36-year-old Johnson, who was contemplating retirement in spring training because of continued pain in his throwing arm.

Washington slumbered through June, struggling to reach the .500 mark. But Johnson, suddenly and mysteriously pain-free, served notice to the rest of the league that he was back, throwing shutouts early and often—including the 100th of his career.

BTW: No other pitcher in major league history would throw 100 shutouts; Johnson finished his career in 1927 with 110.

A 10-game winning streak in late June slung-shot the Senators to first place in a tightly contested AL race that no one was running away with. Sparring through the summer with the Yankees and Detroit, the Senators gradually increased their lead, and by Labor Day the others had slipped to resignation.

All through the year, Johnson had put together an impressive comeback effort, dominating the AL in all major individual pitching statistics. Yet the Senators staff wasn’t all Johnson; rotation mates George Mogridge (16-11) and Tom Zachary (second to Johnson in the ERA race) mirrored Johnson’s road to revival by rising to the occasion after slumping in years before. Overall, Washington’s 3.34 team ERA was easily the AL’s best.

At bat, the Senators had developed a solid core of talent led by first baseman Joe Judge and converted pitchers Leon “Goose” Goslin and Sam Rice. The Senators’ style of hitting was a breathless, dashing style that suited the wide expanses of Griffith Stadium; this was no place for sluggers relying on the home run to comfortably call home, as reflected in the fact the Senators belted 22 all year long—21 of which came on the road.

Like the Senators in the AL, an element of surprise arose in the National League race—and it was reserved for the Brooklyn Robins, who gave the New York Giants all they could handle to the very end.

The Robins were built mostly on experience, their two eldest participants being their best: 33-year-old pitcher Dazzy Vance (the NL leader in wins and ERA) and, most impressively, 38-year-old fan favorite Zack Wheat, who hit a brilliant .375. Only Rogers Hornsby had a better average.

Brooklyn awoke in a big way to start September when it took four straight doubleheaders over a four-day span, leap-frogging the Robins into a pennant race the Giants believed they had already wrapped up. The struggle for first place lasted to the final week, when the Giants extinguished the Brooklyn threat and took the pennant by a game and a half.

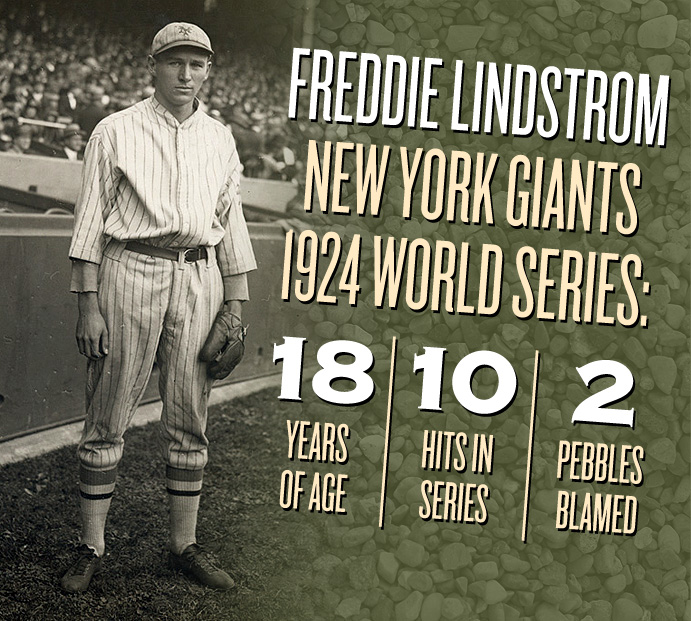

John McGraw’s Giants had the same look and feel of previous years: A healthy mix of talented youngsters and veterans, and a balanced pitching rotation that was reliable, if not dominant. The youth movement continued with the everyday insertion of 20-year-old shortstop Travis Jackson, who batted .302 with 11 home runs; McGraw also brought in a very green 18-year old named Fred Lindstrom, who filled in at third base whenever veteran Heinie Groh had a day off—which wasn’t often.

All the hoopla celebrating New York’s unprecedented fourth straight NL flag quickly muted into controversy.

Speculation grew that members of the Giants had bribed Philadelphia players before their pennant-clinching victory over the Phillies on September 27. Rumor became fact when backup outfielder Jimmy O’Connell admitted he had offered $500 to the Phillies to lay down, saying he was acting on instructions from assistant coach Cozy Dolan—and on behalf of three marquee Giants: Frankie Frisch, George Kelly and Ross Youngs.

Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis, who thought he had scared everyone straight regarding game-fixing in light of his harsh expulsion of the Black Sox participants, opened court. O’Connell, basically caught holding the bag, was immediately expelled from the game. So was Dolan, who pled ignorance without making a denial—guilt enough for the autocratic Landis. Frisch, Kelly and Youngs—the very heart of the Giants’ order, batting a collective .335—vehemently denied allegations of their involvement and, with no evidence outside of O’Connell’s word, were cleared by Landis.

BTW: The exoneration of the star trio infuriated AL president Ban Johnson, who insisted that the World Series be canceled; Landis, the real man in charge, wouldn’t hear of it and ordered it played on.

Walter Johnson was a nervous wreck of a Big Train. After 18 seasons, he was feeling the pressure of pitching his very first World Series game, aware he was a sentimental favorite among fans nationwide.

In the other clubhouse, a player half the age of Johnson also had butterflies rattling around in his belly. Heinie Groh had gone down with an injury in the season’s last week, and into the hot corner stepped Fred Lindstrom as the youngest player ever to start a World Series game.

Johnson was effective enough in Game One, striking out 12 while allowing only two runs, solo homers by Kelly and Bill Terry. However, an old problem arose; he wasn’t getting support. The Senators mustered up just two runs themselves, tying the game in the ninth, and forcing Johnson to toil into the 12th inning. It was then that he came undone, allowing a two-run, bases-loaded single to Youngs that gave the Giants victory.

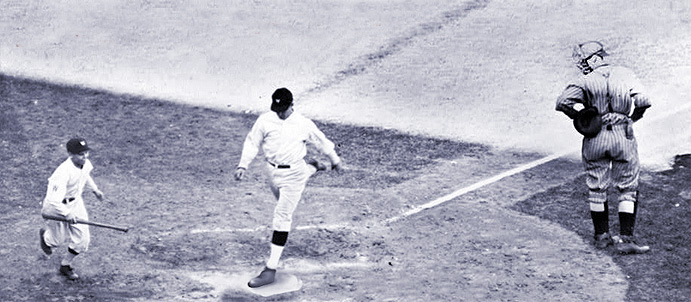

Washington manager-second baseman Bucky Harris, nicknamed “Boy Wonder” for leading the Senators to the World Series at age 27, opens the scoring in Game Seven with a fourth-inning home run.

The Series was tied at two games apiece when Johnson got his second start at the Polo Grounds, but he was far from vintage. Shelled and exhausted for six runs on 13 hits through eight innings, Johnson endured a lifeless final inning in which he gave up three of the runs—and criticism stirred of Senators manager Bucky Harris, now labeled the “Boy Wonder” in getting Washington to the Series, for keeping Johnson on the mound in the fading hope a ninth-inning Senators rally would credit Johnson with his first postseason win.

Answering the critics in Game Six, Harris knocked in both runs during a 2-1 Washington victory to even up the Series—and then opened the scoring in Game Seven at Griffith Stadium with a solo shot in the fourth inning.

After the Giants took back the lead at 3-1, Harris reemerged at the plate in the bottom of the eighth with two outs—and the bases loaded. The Washington manager-second baseman hit a sharp, high bouncer toward Lindstrom at third—and with the acceleration of a rocket, the ball took a rabbit hop high over the teenager’s head. Two runs scored, and John McGraw began to get that awful feeling again.

Now tied going into the ninth, Harris went to his fourth pitcher of the day: Walter Johnson. Just two days after his Game Five start, the Big Train was not dominant, but he had his clutch game working, snuffing out New York rallies constantly over four innings of relief and keeping the game tied going to the bottom of the 12th.

In the tradition of boners, muffs and breakdowns of seasons past, The Giants again became thoroughly luckless when they could least afford to. With one out in the 12th, the Senator’s Muddy Ruel hit a pop-up into foul territory; throwing his catcher’s mask to the turf, it all looked routine for the Giants’ Hank Gowdy—until he got his foot stuck in the mask. His progress impeded, the ball fell uncaught. Given a new life, Ruel doubled. Johnson, now batting, reached first and got Ruel to scoring position when Travis Jackson, having a horrible World Series (three errors and a .074 batting average) bobbled a routine grounder.

The next batter, outfielder Earl McNeely, hit a sharp grounder—right at Lindstrom.

The ball again took a wild hop well above Lindstrom’s head.

Base hit, run scored, Series over.

Lindstrom contended a pebble had led to the exaggerated hops, and he may have been right—though some teammates confided he wasn’t aggressive enough, allowing the ball to play him and not vice versa. The harrowing baptism Lindstrom suffered in Game Seven masked his more productive contributions throughout the Series—a team-leading 10 hits and a .333 average—that helped launch a 13-year career that would eventually land him in the Hall of Fame with a little help from the Veterans’ Committee.

The Senators’ triumph would be a one-time experience. They would win a few more pennants before returning to more memorable form as an annual flop, best reflected in one of baseball’s funniest joke mottoes: “Washington—First in War, First in Peace, Last in the American League.”

But the tasting of total victory in 1924—even if blessed with a little luck—would represent the Washington Senators’ first, last, and only world championship ever.

Forward to 1925: An Intestinal Excess The good life—or too much of it—finally catches up with a bloated Babe Ruth.

Forward to 1925: An Intestinal Excess The good life—or too much of it—finally catches up with a bloated Babe Ruth.

Back to 1923: With Regards to Harry The New York Yankees become one of baseball’s great dynasties at the willful expense of the Boston Red Sox and their Broadway-obsessed owner, Harry Frazee.

Back to 1923: With Regards to Harry The New York Yankees become one of baseball’s great dynasties at the willful expense of the Boston Red Sox and their Broadway-obsessed owner, Harry Frazee.

1924 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1924 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

1924 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1924 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

The 1920s: …And Along Came Babe Baseball becomes the rage thanks to increased offense and the magical presence of Babe Ruth, whose home runs exert a major influence upon the game for ages to come.

The 1920s: …And Along Came Babe Baseball becomes the rage thanks to increased offense and the magical presence of Babe Ruth, whose home runs exert a major influence upon the game for ages to come.