THE YEARLY READER

1931: The Peppering of Philly

Aggressive and colorful, Pepper Martin leads the St. Louis Cardinals in ending the Philadelphia A’s two-year rule over baseball.

The archetypical sight from the 1931 World Series: The highly aggressive, tireless Pepper Martin muscling out another 90 feet to help give the St. Louis Cardinals a crucial advantage over the Philadelphia A’s. (The Rucker Archive)

He pocketed the travel expense money given to him by the St. Louis Cardinals for spring training and played stowaway on a freight train to Cardinals camp in Florida. Jumping off at his destination, he eluded a patrolman watching the yards and raced to a hotel where the team was staying. Dirtied and sweating, he introduced himself to the hotel clerk as the Cardinals’ 27-year-old rookie outfielder, John “Pepper” Martin.

Martin’s disheveled arrival was rule over exception. In uniform, he was often the first player to dirty himself up with a relentless energy at the plate, on the basepaths and in the field. And seven months after making himself known at camp, Pepper Martin would explode into an instant World Series legend with a myriad of exploits, boosting the Cardinals to their second world championship in five years.

As reigning National League champions, the Cardinals had enough strong character and talent already plugged into their roster before Martin arrived via the Hobo Express. He had been a spring training invitee before, but had mostly ended up toiling in the vast Cardinals minor league system, with only a few brief call-ups to the parent club.

By appearance, Martin no longer looked like the rookie type. Gruff and never clean-shaven, his broad muscular shoulders and swift speed were accompanied by the attitude of a cannonball. But in order to play everyday in the outfield, Martin’s best bet was to unseat center fielder Taylor Douthit, a five-year regular and perennial .300 hitter. And although Douthit began the year continuing his everyday role in center—batting .331, no less—St. Louis general manager Branch Rickey traded him to Cincinnati, opening the spot up for Martin. The trade was as much about money as talent; Martin was making $10,000 less than Douthit, and Rickey always said, “better to trade a man a year too early than a year too late.”

BTW: In this case, Rickey’s timing was perfect; at Cincinnati, Douthit would quickly fade and would be out of baseball within two years.

Martin did not disappoint in his new role, batting .300 with decent power. He also stole 16 bases using a then-rare technique called the head-first slide—an even more insane approach, his teammates felt, given that Martin often played without a cup or even underwear. His roguish persona would plant the central seeds for a new breed of Cardinals players, turning the clubhouse into a wild fraternity known as the Gashouse Gang.

For now the Cardinals responded with their greatest year yet, winning 101 games—the first NL team to reach triple figures since the 1913 New York Giants. Though it was the Cardinals’ fourth pennant in six years, it was a chaotic era in which five managers either quit or were fired. That merited congratulations to current St. Louis skipper Gabby Street, who managed to become the first Cardinals boss to start and finish successive seasons since Rickey, in 1923-24.

Despite the absence of the rabbit ball that shot batting averages through the roof the year before, most of the Cardinals lineup continued to hit at or above .300. Left fielder Chick Hafey sweated out an intense batting race to finish on top with a .349 average; first baseman Jim Bottomley finished third, just a point behind. Veteran second baseman Frankie Frisch stole a league-high 26 bases and threw in a .311 average, earning the writers’ respect in their voting him with the first modern-day NL MVP award. The pitching included 24-year-old rookie Paul Derringer (18-8 with a 3.35 earned run average) and 37-year-old Burleigh Grimes (a NL-high 19 wins), still allowed to throw the spitball 11 years after its banishment.

Statistically, the second-place Giants had better team numbers up and down the stat sheet, but lacked the clutch game and fell 13 games back. Meanwhile, the third-place Chicago Cubs witnessed the withering of Hack Wilson. Rewarded for his titanic 1930 season with a $33,000 contract, Wilson stumbled out and produced a fraction of his previous year’s totals, shrinking in both home runs (13, from 56) and runs batted in (61, from 191). The Cubs finished 17 games back.

BTW: Wilson, whose average also dipped nearly a hundred points to .261, physically took out his frustrations on a couple of reporters aboard a train in early September—and was suspended by the Cubs for the rest of the year as a result.

The taking of the NL flag was the easy part for the Cardinals. Waiting on deck for them, again, in the World Series: The Philadelphia Athletics.

Connie Mack’s A’s barreled through AL competition for the third straight year with their best performance in franchise history: 107 wins, 45 losses. It was their third straight year winning over 100, and they aimed to become the AL’s first team to rake in three consecutive World Series crowns.

The New York Yankees once again gave it their almighty best at the plate to unseat the Athletics. They punched across an all-time record 1,067 runs, with six different players each notching 100 or more; as a team they led the league in home runs, batting average, walks and stolen bases. Still, there was no pennant race; the Yankees finished 13.5 games behind Philadelphia at season’s end.

The A’s and Yankees demonstrated—in different ways—the old adage that you’re only as good as your pitching. The Yankees had great stuff from starter Lefty Gomez (21 wins and a 2.67 ERA), but the staff’s depth in general was critically lacking. Philadelphia, on the other hand, relied comfortably on a triad of starters—Lefty Grove, George Earnshaw and Rube Walberg—that provided all the depth the A’s needed, combining to win 72 games, lose 23 and record 14 saves.

Grove, in particular, had the greatest season of a career that would easily earn him a spot in the Hall of Fame. Matching his age with 31 wins, the fiery left-hander lost only four games—and also his temper when a chance to stand alone in the record book was muffed. Having tied the AL mark of 16 straight victories (previously reached by Smokey Joe Wood and Walter Johnson), Grove appeared to be a cinch to break it in his next start against the lowly Browns at St. Louis—but ended up losing 1-0 when a fly ball was botched by outfielder Jim Moore, filling in for an ailing Al Simmons. The misplay led to the game’s only run; Grove spared Moore his fury and saved it for Simmons, cursing the star hitter while literally tearing apart the A’s locker room after the game.

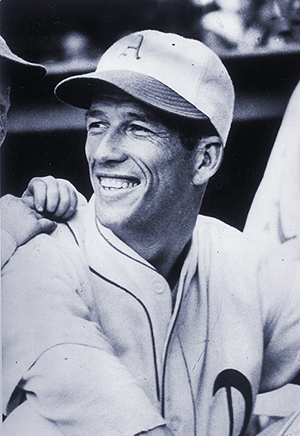

Philadelphia ace Lefty Grove in a lighter moment at the ballpark. Despite a 31-4 record, Grove was best remembered in 1931 for a furious tantrum he threw after narrowly missing out on a chance to break the American League record for most consecutive wins. (The Rucker Archive)

Overall, Al Simmons’ 1931 performance earned far more praise than blame as he won his second consecutive AL batting title—at .390—while ringing out 22 homers and 128 RBIs.

Grove’s personal streak was augmented by several different team streaks as well. The A’s won 17 straight in May—capped by a doubleheader blitzing of the Yankees—built another streak of 13 during July, and had a stretch of 22 straight at home over July and August.

In a World Series rematch of the year before, the favored A’s picked right up where they left off by defeating the Cardinals in Game One. Grove allowed two runs on 12 hits—three of which came off the bat of Pepper Martin, who also stole a base.

Pepper was just warming up.

Martin became the catalyst—a “whole team by himself,” as recounted by The Sporting News—who would first befuddle, then finally foil, the Athletics’ hopes for a third straight title. Though Wild Bill Hallahan pitched a three-hit shutout for St. Louis in Game Two, it was Martin’s baserunning theatrics that sprang to the headlines and kept the game from remaining scoreless. Martin scored the game’s first run in the second inning, stretching a single into a double after the ball was bobbled in the outfield, stealing third, then scoring on a sacrifice fly. He added insurance in the seventh when he singled, stole second, hustled boldly to third on a ground ball hit to the shortstop, then slid home safely on a suicide squeeze bunt.

Though the two teams traded victories over the next four games, Martin’s command of the A’s remained the constant in the mix. He smacked two doubles, a single and scored twice in a 5-2 Game Three win over Grove; in Game Four, he accounted for the Cardinals’ lone two hits off George Earnshaw in a 3-0 loss; and he enjoyed a big day in Game Five, wrapping out a home run, two singles and a sacrifice fly while knocking in four runs in a 5-1 triumph. He was finally held hitless by Grove in Game Six, but still managed to steal a base after walking in an 8-1 loss.

By now being referred to in print as “The Wild Mustang of the Osage,” Martin’s galloping heroics shifted to the outfield in Game Seven. Though held hitless again at the plate, Martin came through with a running catch off a vicious Max Bishop liner—halting a two-run Philadelphia rally in the ninth to end the game and the Series, giving the Cardinals their conquest with a 4-2 victory.

Despite 0-for’s in the final two games, Martin still batted .500 with 12 hits—tying a Series record held by Joe Jackson and Sam Rice, both of whom needed more at-bats to get there. Within the carnage was four doubles, a home run and five stolen bases. Without him, the Cardinals batted just .205—and the A’s, most likely, would have secured their three-peat.

In Martin’s shadow stood two outstanding pitching efforts from the Cardinals. Burleigh Grimes, a question mark coming into the series after a late-season bout of appendicitis, was sharp in his two starts—winning both while allowing just nine hits in 17.2 innings. Wild Bill Hallahan also silenced the A’s, allowing one run over two starts and earning the save in Game Seven by stopping Philadelphia’s ninth-inning rally.

A case of finger pointing filled the A’s clubhouse and spilled out to the media after the Series. George Earnshaw was upset with catcher Mickey Cochrane’s failure to extinguish Martin’s basestealing, wishing rookie Joe Palmisano would have been there instead. Cochrane, in turn, criticized Earnshaw for not paying more attention to Martin on the basepaths and keeping him in check. Manager Connie Mack, playing the gentleman as always, blamed no one, congratulated the Cardinals and defended Cochrane for just being able to suit up despite a series of bruises and bumps that had him worn down by season’s end.

Touted as the next Ty Cobb—a burdensome assessment—Pepper Martin would suffer through an injury-riddled 1932 campaign, but would bounce back to have a series of solid years throughout the mid-1930s. Yet he never reached pure superstardom and was relegated to a part-time role by 1937. Martin’s career would come to an end in 1940 with a .298 batting average, 1,227 hits and 146 steals—not exactly Hall-of-Fame credentials.

But Pepper Martin’s character and brilliant blast of fame from the 1931 World Series leaves him as one of the most remembered players not enshrined at Cooperstown.

Forward to 1932: The So-Called Shot Babe Ruth’s historic and highly debated gesture gives a hostile World Series its flashpoint.

Forward to 1932: The So-Called Shot Babe Ruth’s historic and highly debated gesture gives a hostile World Series its flashpoint.

Back to 1930: The Big Blastcast of 1930 Outrageous feats of offense abound as the live ball era reaches its peak in eye-opening fashion.

Back to 1930: The Big Blastcast of 1930 Outrageous feats of offense abound as the live ball era reaches its peak in eye-opening fashion.

1931 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1931 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

1931 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1931 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

The 1930s: Dog Days of the Depression The majors take a hit from the Great Depression as both attendance and bravado are on the wane—until newborn icons Joe DiMaggio and Ted Williams emerge to rejuvenate the game’s passion for the fans.

The 1930s: Dog Days of the Depression The majors take a hit from the Great Depression as both attendance and bravado are on the wane—until newborn icons Joe DiMaggio and Ted Williams emerge to rejuvenate the game’s passion for the fans.