THE YEARLY READER

1946: It’s Good to be Home

The majors return to normalcy as Americans can comfortably and fully concentrate on the game—and do so in record numbers, with attendance nearly doubling.

A Boston Red Sox team loaded with stars and veterans pose in a sight not seen for nearly four years. American League champions in 1946, the Red Sox included only one everyday regular and one starting pitcher held over from the replacements and scrap talent of the year before. (The Rucker Archive)

It all seemed too good to be true. In one glimpse, the huge crowd at Washington’s Griffith Stadium could see Ted Williams, Bobby Doerr, Dom DiMaggio, Buddy Lewis, Mickey Vernon and more.

What felt like an eternity had passed since a lineup of this magnitude graced a major league ballpark. But when the Boston Red Sox and Washington Senators readied to play ball on Opening Day, 1946, the faithful in the stands and at major league ballparks elsewhere pinched themselves to make sure that the war was over, the players were back and that baseball could resume its normally scheduled aspirations at full strength.

A year earlier, Snuffy Stirnweiss played like a MVP-caliber ballplayer amid vastly inferior talent. With rosters back to full strength in 1946, Stirnweiss was just another major leaguer—but at least he was one of the few wartime replacements to keep his job. (The Rucker Archive)

Even if their job security wasn’t mandated, the regulars were likely to get their pre-war jobs back anyway—proven by the fact that two-thirds of all everyday players during the 1945 season went back to the bench or worse for 1946. Those lucky to remain on the field knew the quality of the game would inevitably shoot up at the expense of their individual numbers. The poster child for such survival was New York Yankees infielder Snuffy Stirnweiss, the two-time defending American League leader in hits, stolen bases, runs and triples. In 1946, with the big boys back in town, Stirnweiss degenerated into a common player—batting just .251 with otherwise piecemeal potency.

As owners attempted to oblige the overflow of talent, some unwelcome relief came from south of the border. A Mexican tycoon named Jorge Pasquel barged into the States loaded with bags of money in an attempt to lure major leaguers and bolster his Mexican League. He got lots of attention—and some notable players to come back with him. Some 20 players agreed to join Pasquel’s ranks, but when commissioner Happy Chandler warned that any player going to Mexico would receive a five-year banishment from the majors back home, several Pasquel signees performed an about face—including St. Louis Browns slugger Vern Stephens, who had inked for a guaranteed $50,000 to play in Mexico.

BTW: Among those tempted by Pasquel who ultimately said no was Ted Williams, who reportedly was offered $500.000.

The majors’ first postwar season met with staggering success at the gate. The return of the star players, coupled with the sense that watching a ballgame was no longer the guilty pleasure it once was in time of war, sent fans swarming to ballparks in droves.

Major league attendance in 1946 nearly doubled its turnstile count of the year before—which happened to be the old record. All 16 teams saw increased attendance, and clubs that before could only dream of drawing a million fans—teams like the Senators and the Philadelphia Phillies—surpassed the magic number in 1946. In all, five teams drew over a million fans for the first time. The Yankees did one better on the rest, becoming the first team ever to draw two million.

BTW: New York City’s claim as the center of the baseball world would strengthen in 1946, with its three big league ballclubs attracting a combined 5.3 million fans through the turnstiles.

Feelin’ Like a Million for the Very First Time

Entering 1946, only five major league franchises had ever topped one million in season attendance; by the end of the year, five more joined the club. The other six teams would complete the list within 10 years.

Up the road in Boston, the Red Sox doubled their previous gate to 1.4 million; postwar prosperity certainly had something to do with it, but so did the team’s performance, which resulted in its first pennant in 28 years. It was the long-awaited breakthrough for the Red Sox after 13 years of ownership under Tom Yawkey, who stood the organization back up on its feet after rescuing it from the post-Harry Frazee depths of the late 1920s and early 1930s. Under Yawkey, the Red Sox were given their modern-day interpretation as a competitive and entertaining ballclub, immensely rich on character and strong hitting.

Boston bolted out of the gate, thanks to a club record 15-game winning streak in May and a sensational start by Ted Williams, who at the age of 27 was well preserved after serving four years as a Navy pilot. The Splendid Splinter complemented his quick start with four hits (including two home runs) in the All-Star Game, played at Boston’s Fenway Park on July 9.

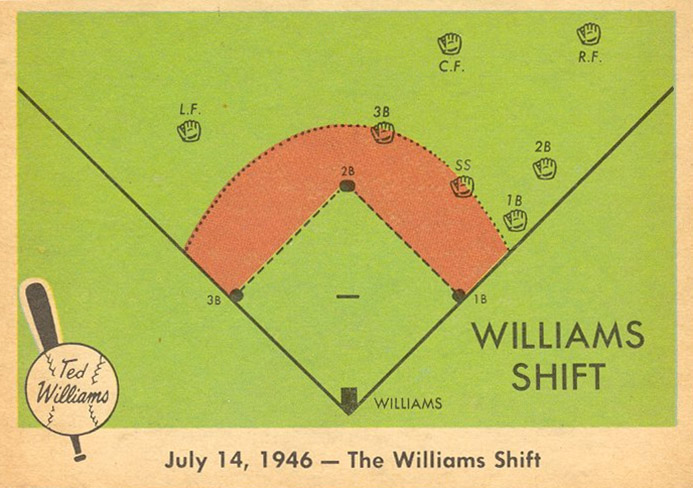

When, five days later, Williams clubbed three homers and knocked across eight runs in a game against the Indians, Cleveland manager Lou Boudreau went to extremes. Noting that Williams was a left-handed pull-hitter, he radically stacked his defense to the right side of the field, positioning only the third baseman and left fielder west of the second base bag. Though used in rare doses over previous generations on other players, this variation of what would be known as the “Williams Shift” would stick.

BTW: The “shift” would be employed sparingly until it became a common tactic against dead-pull hitters starting in the 2010s.

Getting Shifty With Ted

When Ted Williams came to the plate against Cleveland on July 14, Indian manager Lou Boudreau ordered a radical defensive alignment in which almost everyone on the field played right of second base, as exhibited on this 1959 Fleer baseball card. The alignment would forever be known as “The Williams Shift.”

The shift slowed—but did not stop—either Williams or the Red Sox. And it was Williams who served poetic justice when, on September 13, the slow-footed slugger hit the opposite way and snuck in the first and only inside-the-park home run of his career against Boudreau and the Williams Shift. The homer accounted for the game’s only run, which clinched the AL pennant for Boston.

Williams’ 1946 performance—a .342 batting average, 38 home runs and 123 RBIs—finally cemented him with a long-overdue Most Valuable Player award voters had previously robbed him of at least twice. But Williams also got plenty of support, especially from a strong-hitting Red Sox infield that included first baseman Rudy York, the former Detroit slugger who knocked in 119 runs; second baseman Bobby Doerr, who punched in 116; and shortstop Johnny Pesky, who led the AL with 208 hits while batting .335. The team’s league-high .271 batting average made life easy for its pitching staff, led by second-year hurler Boo Ferriss (25 wins against six losses) and veteran Tex Hughson (20-11).

Under manager Joe Cronin, who now spent all his time in the dugout after a 20-year playing career, the Red Sox performed an AL-record 33-game upgrade from the year before—though the wartime conditions of 1945 deserved the distinction with an asterisk.

The defending AL champion Detroit Tigers weren’t much to talk about beyond the league-leading exploits of slugger Hank Greenberg and pitcher Hal Newhouser, finishing in second place 12 games back of the Red Sox; the Yankees settled for third place as manager Joe McCarthy, angered that executive Larry MacPhail was pushing his buttons once too often, resigned just 35 games into the season.

Over in the National League, world peace renewed the war between two bitter rivals: The St. Louis Cardinals and Brooklyn Dodgers. Yet the Cardinals spent the early months of the year duking it out with themselves before stepping into the ring with the Dodgers.

Billy Southworth, who piloted the Cardinals to an average of 102 wins over the previous five seasons, was lured away to the Boston Braves—joining ex-St. Louis ace pitcher Mort Cooper. The Cardinals were also heavily targeted by Jorge Pasquel; three players left for Mexico, including pitcher Max Lanier—who won his first six games in St. Louis before eloping southward. It could have been much worse; marquee performers Stan Musial, Enos Slaughter and Whitey Kurowski were all reportedly close to signing as well before backing off.

Danny Gardella (left) sits next to Mexican League tycoon Jorge Pasquel, who lured Gardella and a handful of other major leaguers south of the border with generous amounts of money. Banned in the States for his actions, Gardella later sued Major League Baseball and eventually settled out of court. (The Rucker Archive)

A best-of-three playoff between the two teams, the first of its kind, only prolonged Brooklyn’s agony of the inevitable. St. Louis took the tiebreaker in two games, holding off furious late-inning Dodger rallies in both to place a victorious face on its own late-season run. But in triumph, the powerful Cardinals had to hand it to Brooklyn for sticking with it all the way in spite of a patchwork, platooned roster orchestrated by manager Leo Durocher, who had only three players log as many as 125 games for the otherwise beat-up or inexperienced Dodgers.

As rookie Cardinals manager Eddie Dyer prepared a more conservative version of Lou Boudreau’s defensive shift against Ted Williams for the World Series, he soon got word that it all might be moot. Williams suffered a badly bruised right elbow after being drilled by a Mickey Haefner pitch in a warm-up exhibition against a group of AL All-Stars. Williams rested up but did prep himself to play, albeit in pain, against St. Louis.

The World Series became a seesaw event through the first six games, as the Cardinals and Red Sox evenly traded victories. In Game Seven at St. Louis, Boston outfielder Dom DiMaggio—Joe’s younger brother—hit a two-run, eighth-inning double to erase a 3-1 Cardinals lead and tie things up. But the real theatrics were yet to come.

Enos Slaughter, a hustling personality who, like Williams, was also suffering from an achy elbow, opened the bottom of the eighth for St. Louis with a single. But as the go-ahead runner at first base, Slaughter stood frustrated and stuck while the Red Sox retired the next two batters.

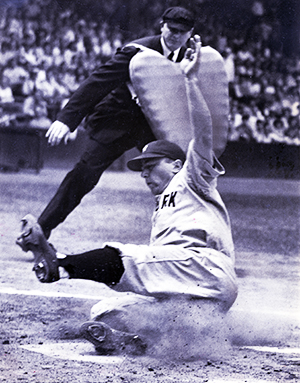

When the next batter, Harry Walker, lined a single into center field, Slaughter went flying around the bases like a bat out of hell. Typically able to reach third on such a play, Slaughter sped against both convention and the stop sign frantically being signaled by St. Louis third base coach Mike Gonzales. Meanwhile, Johnny Pesky took the throw from the outfield and, stunned to see Slaughter dashing homeward, briefly hesitated in making the relay to the plate. When he did, he threw late and offline. Slaughter slid in with what would be the Series-winning run, as Cardinals pitcher Harry Brecheen held the Red Sox scoreless in the ninth to ice the championship.

BTW: Pesky always maintained he did not hesitate on the relay, though the element of surprise most likely caused a less than perfect throw to the plate.

A healthy Ted Williams might have spared the Red Sox a Game Seven and given them the championship, but Teddy’s ballgame was not at his best with the bad elbow. He batted just .200 with no extra-base hits and a single RBI in what would be, over a brilliant 19-year career, his only World Series appearance.

To tens of millions of baseball fans, they were just happy to see Enos Slaughter making front page headlines as opposed to the slaughter that war had wrought upon world civilization over the previous six years. Everything seemed back to normal, the way it was before—and better.

But with Jackie Robinson on deck, the game was still a year away from becoming complete in the eyes of all.

Forward to 1947: The Arrival of Jackie Robinson Baseball’s color barrier is knocked down, but not without intense prejudicial resistance.

Forward to 1947: The Arrival of Jackie Robinson Baseball’s color barrier is knocked down, but not without intense prejudicial resistance.

Back to 1945: Hank’s Heroic Rescue As World War II comes to an end, Hank Greenberg makes the first and most celebrated return to baseball.

Back to 1945: Hank’s Heroic Rescue As World War II comes to an end, Hank Greenberg makes the first and most celebrated return to baseball.

1946 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1946 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

1946 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1946 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

The 1940s: Of Rations and Spoils The return to a healthy economy and the breaking of the color barrier helps baseball reach an explosive new level of popularity—but not before enduring with America the hardship and sacrifice of World War II.

The 1940s: Of Rations and Spoils The return to a healthy economy and the breaking of the color barrier helps baseball reach an explosive new level of popularity—but not before enduring with America the hardship and sacrifice of World War II.

Bobby Doerr talks of his time with the Red Sox, Ted Williams, the intriguing Moe Berg, and why the Red Sox weren’t cursed.

Bobby Doerr talks of his time with the Red Sox, Ted Williams, the intriguing Moe Berg, and why the Red Sox weren’t cursed. Dan Litwhiler recalls Stan Musial, coaching Steve Garvey and Kirk Gibson at Michigan State and how he came about inventing baseball’s radar gun.

Dan Litwhiler recalls Stan Musial, coaching Steve Garvey and Kirk Gibson at Michigan State and how he came about inventing baseball’s radar gun.