THE YEARLY READER

1951: The Shot Heard ‘Round the World

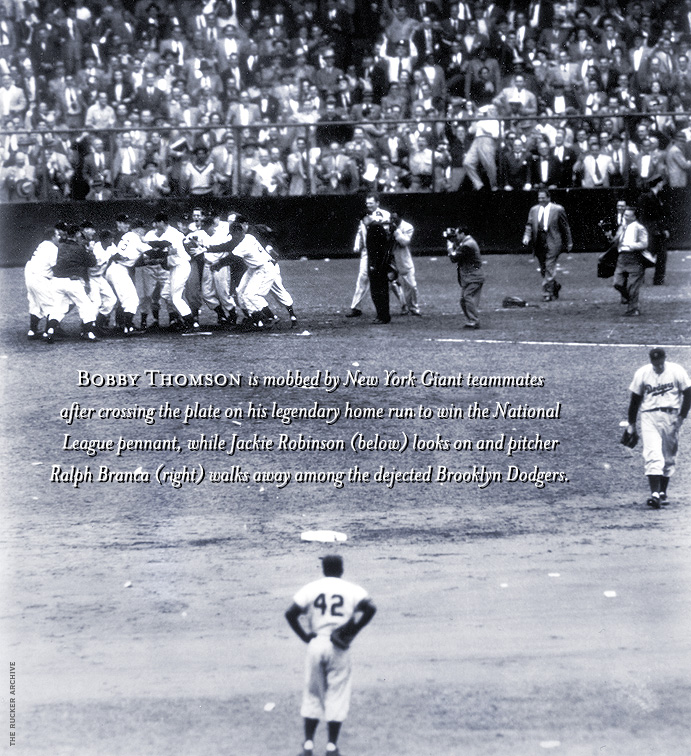

An amazing late-season comeback by the New York Giants reaches legendary proportions with Bobby Thomson’s unforgettable, game-winning home run in a tiebreaking playoff against the archrival Brooklyn Dodgers.

Ralph Branca grew up a big fan of the New York Giants.

On October 3, 1951, he probably wished he was still one.

An eight-year veteran of the archrival Brooklyn Dodgers, the big 25-year-old right-hander was called upon to quell a desperate ninth-inning rally by his boyhood heroes. All that stood between Branca and a spot in the World Series was Giants slugger Bobby Thomson.

What happened next is often cited by baseball players and historians alike as the game’s most memorable moment, ever.

Until that moment, Branca had yet to attract enough bad luck to justify the “13” on the back of his uniform. He won 21 games in 1947, the first of three straight years in which he was selected to the National League All-Star team. He slipped in 1950 to 7-9 and was relegated to the bullpen. But in 1951, Branca won his way back into the rotation after springing out to a strong start.

Branca was the third main man in a Brooklyn rotation that included two 20-game winners: Don Newcombe (at 20-9) and 36-year-old Preacher Roe, who was particularly stunning with 22 wins and only three losses. But the Dodgers’ pitching was overshadowed by the team’s offense, which led the NL in almost every major category. First baseman Gil Hodges became the first Dodger ever to hit 40 home runs; his 103 runs batted in were joined by two others reaching the century mark, Duke Snider (101) and catcher Ray Campanella—whose 108 were part of a package that, with a .325 average and 33 homers, earned him the first of three NL Most Valuable Player awards. But Jackie Robinson was still the heart and soul of the Dodgers lineup, batting .338 with 106 runs scored, 19 homers and 25 stolen bases.

Brooklyn shot out of the gate in 1951, eager to make up for its lost opportunity against Philadelphia on the final day of the 1950 season. While the Dodgers’ lead was not always prohibitive, their all-around strengths forged some mental resignation among those trailing behind in the standings.

Meanwhile, upriver from Brooklyn, the New York Giants were downtrodden. They plunged to a 2-13 start and became preoccupied with catching the .500 mark, let alone the Dodgers. Bad starts were becoming a bad habit for the Giants; they had to win 50 of their final 72 games the year before to look good after crawling through the spring. Manager Leo Durocher wondered how long he could be allowed to endure getting off on the wrong foot; he’d been fired at Brooklyn three years earlier for a slow start there.

As the Giants struggled to distance themselves from the basement, Durocher furiously lobbied the front office to bring up a solid gold prospect ordained as a five-tool player—one who excelled in all aspects of the game—and was hitting a spectacular .477 in 35 games for the Minneapolis Millers, the Giants’ chief farm club. Finally in late May, Durocher got his wish; the Giants ran an ad in Minneapolis newspapers apologizing to local fans for taking away their beloved star, Willie Howard Mays.

The 20-year-old Mays was a man of lightweight disposition and heavyweight talent; when he first began turning heads on ballfields in his home state of Alabama, a Giants scout adamantly told his superiors back home: “Don’t ask any questions. You’ve got to get this boy.” But once promoted to the majors, Mays was initially not the lifesaver the Giants were counting on. He managed just one hit in his first 26 at-bats (though the one hit was a home run off of Boston Braves ace Warren Spahn), and a defeated Mays asked Durocher to be sent back to Minnesota. Durocher convinced Mays otherwise as only Durocher could, chewing him out with a dose of tough love. It apparently worked; Mays stayed and ultimately completed his first big league year hitting a respectable .274 with 20 homers.

BTW: Spahn on Mays’ first home run: “For the first sixty feet, it was a hell of a pitch.”

Rookie Willie Mays steals home for the Giants in a late August doubleheader against the Chicago Cubs. After a tough first week in the majors, the 20-year-old Mays would come around and win Rookie of the Year honors. (Associated Press)

Mays’ presence took the load off the rest of the Giants lineup, which included shortstop Alvin Dark, flourishing in his second year at New York after being traded from the Braves; left fielder Monte Irvin, the team’s first African-American player from 1949, who hit .312 with 24 home runs and a team-leading 121 RBIs; and Bobby Thomson, sometimes outfielder, sometimes third baseman, always damaging on opposing pitchers. A native son of Glasgow, Scotland, Thomson was on his way to batting .293 with a career-high 32 homers.

The addition of Mays also eased the burden of the New York pitching staff, led by a pair of 23-game winners in Sal Maglie and Larry Jansen.

The Giants regrouped with Mays and put themselves within striking distance of Brooklyn. But when the Dodgers swept the Giants in early July to re-up their lead to seven games, Dodgers manager Chuck Dressen, feeling frisky after being ejected from both ends of a doubleheader his team had won, boasted: “The Giants is dead. They’ll never bother us again.”

If savored as chalkboard fodder, the Giants had a delayed effect in responding, as the Brooklyn lead grew to a near-insurmountable 13 games a month later. Then it happened.

The Giants won. And won. And won again. It became a team possessed. Sixteen straight victories later, the Giants had knocked eight games off the Brooklyn lead. The Dodgers got the message and spent most of September keeping the Giants at arm’s length. But in the season’s final week, Brooklyn couldn’t hold onto a three-game lead, thanks in part to a seven-game New York win streak to end the schedule.

Tied for first place going into the season’s final day, the Giants won early at Boston and then waited out with incredulity as Brooklyn had to exert two comebacks and extra innings to force a postseason tiebreaker with a 9-8 win at Philadelphia. Jackie Robinson emerged as the Dodgers’ hero of the day, first making a season-saving catch of an Eddie Waitkus liner in the 12th from which he nearly jammed his shoulder; recovered, Robinson hit a solo home run in the 14th to guarantee a season extension.

BTW: Taking the loss for the Phillies was Robin Roberts, who beat the Dodgers in the historic 1950 season finale.

Ralph Branca started Game One of a best-of-three playoff against the Giants and lost it, 3-1, thanks solely to two New York homers—one a two-run shot off the bat of Bobby Thomson. The Dodgers stormed back with a 10-0 thrashing in Game Two behind rookie pitcher Clem Labine. That set up the winner-take-all affair at The Polo Grounds.

BTW: It was one of two career shutouts for Labine, who would spend the bulk of his career as a reliever.

Bobby Thomson completes his circuit on the home run that won the NL pennant, while jubilant Giant manager Leo Durocher and second baseman Eddie Stanky (wearing jacket) can hardly contain themselves. (The Rucker Archive)

Dark scored to make it 4-2 on a double by the next batter, Whitey Lockman—who became the tying run in scoring position. (Mueller badly hurt his ankle sliding into third base on the play, and the game was stopped for over 10 minutes as he was taken off the field.) With Thomson emerging to the plate, Dressen brought in Branca, loser of six of his last seven decisions on the mound. Thomson’s day was not going well; though he had knocked in the first Giants run on a sacrifice, he had committed a baserunning gaffe and was enduring a tough defensive day at third base.

With first base open, Branca could have given Thomson a free pass to first base—setting up the force at any base with one out. But this also meant putting the winning run on first—with Willie Mays next to hit.

So Branca went after Thomson.

After taking the first two pitches, Thomson offered at Branca’s next delivery and took the swing of a lifetime. Lined down the Polo Grounds’ miniscule left-field line, the ball tucked itself into the second deck not more than 300 feet away from home plate. Thomson’s three-run homer won the game and the pennant, 5-4, capping one of baseball’s greatest season comebacks with, not so arguably, its greatest moment ever.

The Brooklyn Dodgers were left with the cold, stinging reality that, for the third time in six years, they had lost a chance to take the NL pennant on the season’s last day.

On the quieter side of the New York baseball world, the Yankees didn’t deliver any stellar comebacks from the deep recesses of the American League standings. Rather, they fought off a new round of roster handicaps and some tough competition from both the Cleveland Indians and Boston Red Sox to take their third straight AL pennant.

The Yankees survived by five games in spite of the military acquisition of Whitey Ford and an offense that showed no real dominance. Lowlighting the individual performances was 36-year-old Joe DiMaggio, dragging his beat-up body through what would be his final year as a player with a .263 batting average and 12 home runs. The savior element rested within the Yankees rotation, with two 21-game winners in Ed Lopat and Vic Raschi. Allie Reynolds contributed 17 more wins, seven by shutout—and two of those were no-hitters, one each against the Indians and Red Sox.

Why Stop at One?

Allie Reynolds’ two no-hitters in 1951 made him just one of six pitchers in the history of the majors to achieve such a feat in one season.

Just a day after Bobby Thomson’s miracle theatrics, the World Series commenced with the Yankees taking on a Giants squad on an all-time emotional high. The momentum carried over well, as outstanding pitching gave the Giants victories in two of the first three games. Then they settled down—and with it, the Yankees settled in, winning Games Four and Five at the Polo Grounds by a combined score of 19-3. The Yankees held off a furious ninth-inning rally by the Giants in Game Six to win, 4-3, and clinch their third straight championship; Yankees pitcher Bob Kuzava put the lid on a Giants comeback after entering the ninth with the bases loaded and no one out, retiring the final three batters—the second of those being Thomson, whose bid for a second shot heard ‘round the world died in Yankee Stadium’s voluminous left field nicknamed Death Valley.

Fifty years after the Miracle at Coogan’s Bluff, as Thomson’s home run is often nicknamed, a Wall Street Journal article revealed that the Giants’ big comeback of 1951—and perhaps Thomson’s home run—was the result of a complex scheme the Giants had developed to steal signs and give their batters a heads-up on what kind of pitch was coming. Many surviving members of the 1951 Giants said, for the most part, that the story was true; Ralph Branca had heard about it as early as 1954, but didn’t squawk about it since it wasn’t going to change anything about 1951. When Thomson, a kind old man nearing 80 years of age, was asked by the Journal whether he was tipped off before his historic home run against Branca, it was reported that he was initially evasive and roundabout in response.

Thomson finally said: “My answer is no.”

Forward to 1952: The Education of Mickey Mantle How the next in line to inherit the throne as the New York Yankees’ icon nearly caved under the pressure.

Forward to 1952: The Education of Mickey Mantle How the next in line to inherit the throne as the New York Yankees’ icon nearly caved under the pressure.

Back to 1950: Gee Whiz! The Philadelphia Phillies overcome decades of futility and embarrassment with a rare National League pennant.

Back to 1950: Gee Whiz! The Philadelphia Phillies overcome decades of futility and embarrassment with a rare National League pennant.

1951 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1951 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

1951 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1951 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

The 1950s: A Monopoly of Success Though described as a golden age for baseball, most major league teams find themselves struggling—unless you’re in New York City, where the Yankees, Dodgers and Giants hog the World Series podium from 1950-56. But as the decade winds to a close, the euphoria of Big Apple baseball will rot overnight.

The 1950s: A Monopoly of Success Though described as a golden age for baseball, most major league teams find themselves struggling—unless you’re in New York City, where the Yankees, Dodgers and Giants hog the World Series podium from 1950-56. But as the decade winds to a close, the euphoria of Big Apple baseball will rot overnight.

Herman Franks explains his refusal to discuss his possible role in stealing signs during the 1951 pennant race, gives his opinion on steroids and the best team he ever managed.

Herman Franks explains his refusal to discuss his possible role in stealing signs during the 1951 pennant race, gives his opinion on steroids and the best team he ever managed. Gil Coan discusses a short but fine baseball career that included a skull fracture, two years hitting above .300 and a race against a horse.

Gil Coan discusses a short but fine baseball career that included a skull fracture, two years hitting above .300 and a race against a horse.