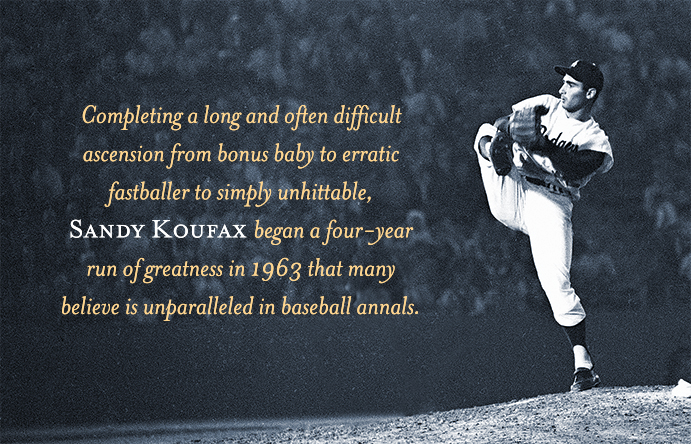

THE YEARLY READER

1963: The Sandman Cometh

Southpaw standout Sandy Koufax emerges as a one-of-a-kind pitcher, leading the Los Angeles Dodgers to a World Series sweep of the New York Yankees.

(Associated Press)

Sandy Koufax was the rarest of kids growing up in baseball-crazy Brooklyn during the early 1950s: One with the talent to be a future Dodgers star, but with the devotion to be something else—an architect, maybe, or even a basketball player.

Nonetheless, Koufax—a handsome, modest-looking teenager who possessed a killer fastball—would follow a long and rocky path of destiny and, by 1963, finally emerge as the pride of the Los Angeles Dodgers.

The journey to such accolades, long after he first donned Dodger blue, seemed destined not for greatness but, instead, a dead end.

Koufax’s major league career could easily be broken down into Parts I and II. Part I is the story of Koufax, the bonus baby-faced Dodger struggling to evolve with an electrifying fastball that often missed the strike zone. Such wildness became the stuff of legends. Teammate Duke Snider said going into the batting cage against Koufax was like playing Russian roulette. Even those standing around weren’t safe, as Koufax would sometimes miss the cage altogether. Before long he was known as “Sandy the Scatter Arm.”

Through Koufax’s first six years, there were few if any signs of advancement, as underscored by a collective 36-40 record. He was always among the National League leaders in strikeouts and twice led the NL in opposing batting average, but those impressive numbers were a statistical smokescreen to the overabundance of walks that always got him into trouble. On occasion Koufax would get into a genuine groove, as in a 1959 game when he struck out 18 San Francisco Giants to tie Bob Feller’s 1938 single-game record. But by the end of the 1960 season, in which Koufax finished 8-13 with a 3.91 earned run average, his ability to punch a hole through the brick wall of progress had stalled to the point that he considered quitting.

Part II starts on the day Koufax’s battery mate, catcher Norm Sherry, decides to take a look at the beleaguered pitcher’s delivery. He gave Koufax two tips: One, alter your windup so you can see the strike zone; two, don’t pitch to make hitters miss, but to make them hit it. At the same time, Koufax had mastered a devastating curve ball that could bend up to two feet in any direction.

Almost overnight, Sandy Koufax was reborn. In 1961 he won 18 games and led the NL in strikeouts for the first time—but without the inundation of walks, which he cut down by a third. Koufax would improve even more in 1962, further reducing the number of walks and, finally, his ERA—which at 2.54 led the league.

BTW: For Koufax, it was the first of five straight ERA titles, a run unmatched in major league history.

The Two Faces of Sandy Koufax

The first six years of Sandy Koufax’s career—full of wild, inconsistent results—differ substantially with the last six, in which he took center stage as one of the great pitchers of all time.

In 1963, Koufax’s level of success reached the stratosphere—where it would stay for the balance of his career. He won 25 games against just five losses, blanking his opponents 11 times—eclipsing the nine shutouts he had accumulated in his whole career to date. Over a prodigious 311 innings, Koufax struck out 306—breaking the NL record he himself had set two years earlier—while walking only 58. Batters hit just .189 against him with a .230 on-base percentage; both figures were the best the NL had seen since the days of Christy Mathewson.

BTW: Among Koufax’s 11 shutouts was his second career no-hitter, on May 11 against the Giants.

Inspired, the rest of the Los Angeles staff banded with Koufax to deliver a 2.85 team ERA that was the NL’s best. Chief among Koufax’s partners was Don Drysdale, won who 19 games of his own with a 2.63 ERA (somehow, he lost 17); and reliever Ron Perranoski, who recorded a 16-3 record with 21 saves and a sparkling 1.67 ERA.

Dodgers pitching practically carried the entire team on its back as the team held onto first place, bailing out a weak offense—a pattern that would continue at Los Angeles in good times and bad throughout the rest of the 1960s. The lineup was not your father’s Dodgers of Ebbets Field lore; as a team they placed fourth in batting average, sixth in runs scored, eighth in slugging percentage and ninth in home runs. Tommy Davis and Frank Howard remained the Dodgers’ two big hitters in 1963 but had their RBI totals cut virtually in half from 1962. Maury Wills stole 40 bases after swiping a record 104 the year before.

The Dodgers’ second NL pennant in Los Angeles didn’t come easily, surviving a late rush from a St. Louis Cardinals squad that won 19 of 20 into September and at one point closed the Dodgers’ lead to a single game. Finishing six back of Los Angeles, the Cardinals could not provide the perfect send-off for Stan Musial, who at 42 was preparing for retirement and, after 17 years of postseason absence, barely missed one last crack at a World Series.

BTW: Musial batted .255 but did provide 12 home runs and 58 RBIs in only 337 at-bats.

The strengthening of the Dodgers pitching staff, offset with the team’s weak hitting, was indicative of baseball in general. Major league owners, spurred on by commissioner Ford Frick—still smarting over Roger Maris’ record-breaking, asterisk-sullied home run mark of two years earlier—ordered for an enlargement of the strike zone as a reaction to a recent rise in home run production.

BTW: This was actually a compromise for Frick; he wanted to legalize the spitball, but found scant support.

Such rises in homers had actually been modest, while batting averages hadn’t risen at all—but both suffered under the new zone beginning in 1963. The collective NL batting average dropped from .261 to .245, while home runs and runs scored fell off by 15%. The lowly New York Mets bottomed out at .219, just a shade lower than the Houston Colt .45s—a team that belted just 62 home runs, only one more than Maris himself had hit a few years earlier. The American League’s drop-off was not as steep but just as telling, with the Minnesota Twins leading the league in batting—at only .255.

Numbers were all relative for the New York Yankees, who had enough strength in all facets of their game to easily capture their fourth straight AL pennant.

Winning 104 contests and finishing 10.5 games ahead of the second-place Chicago White Sox was a triumph of Yankee depth, rising to the occasion as their two big boomers—Maris and Mickey Mantle—both missed roughly half the season to injuries.

Two players in particular filled the slugging void left vacant by the M&M Boys. One was first baseman Joe Pepitone, who with 27 homers and 89 RBIs was enjoying his first year as an everyday starter on the field; he was enjoying it off the field as well, living the high life in ways that raised even the eyebrows of veteran Yankee partiers like Mantle and Whitey Ford. The other was Elston Howard, who became the team beacon by hitting .287 with a team-high 28 home runs while earning a Gold Glove behind the plate as catcher. Elston connected on enough clutch hits that, by the end of the year, he was named the first African-American to win the AL’s Most Valuable Player award.

The Yankees’ dominant starting rotation was all the depth the team needed on the mound. Workhorses Ford (a league-leading 24 wins against seven losses) and Ralph Terry (17-15 with an AL-high 18 complete games) were joined at the top by 24-year-old Jim Bouton, who broke through with a 21-7 record and a team-best 2.53 ERA.

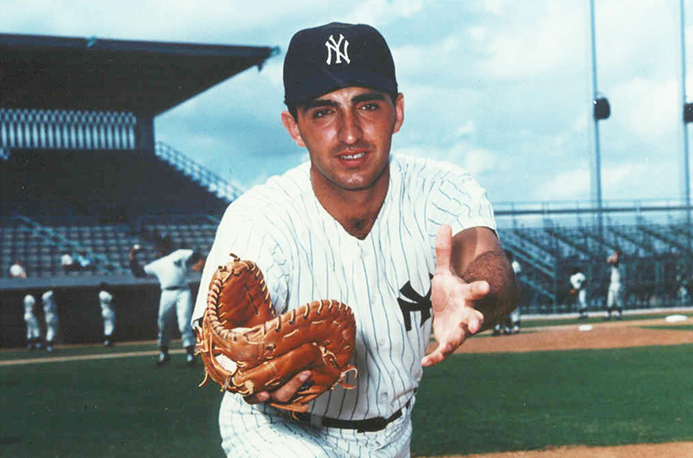

Dryin’ and Drivin’ with Joe Pepitone

Signed on with the Yankees in 1962 as a highly touted first baseman, Joe Pepitone was among the first ballplayers to embody the 1960s Jet Set within baseball circles. Pepitone displayed his flamboyance by driving flashy cars and speedboats and, most famously, for being the first player to bring a hair dryer into the clubhouse. More notoriously, the Brooklyn-born Pepitone made friends with some local goodfellas who offered to help win him the Yankees’ first base job by breaking the legs of incumbent Bill Skowron (Pepitone said no thanks, and Skowron would be traded anyway after 1962).

Pepitone would play 12 years in the majors—eight with the Yankees—batting .258 with 219 home runs while winning three Gold Gloves for his slick fielding. He tried Japan in 1973 but became a poster child for the argument against signing over-the-hill Americans to big fat contracts; he hit .163, endlessly complained and came home after just two weeks.

Hitters in the National League had long since discovered how terrifying Sandy Koufax had become. And now, for Game One of the World Series at New York, the Yankees were officially about to become the first American League team to get the same message.

Tony Kubek, Bobby Richardson, Tom Tresh, Mantle and Maris were the first five Yankee batters to face Koufax. They all struck out. When those same five came up a second time, all but Maris struck out again. Overall, Koufax retired the first 14 New York batters, and by the end of the game he’d struck out 15, a Series record for the time. Richardson, who had whiffed 22 times all year in 668 plate appearances, was retired on strikes three times by Koufax. The shutout was spoiled when Tresh homered in the eighth inning, but by then the Dodgers had long since taken care of Whitey Ford to win the opener, 5-2.

As they did all year long, fellow Los Angeles starters reveled alongside Koufax. Game Two starter Johnny Podres, a veteran of the Dodgers-Yankees wars of the mid-1950s, silenced New York into the ninth and got out with a 4-1 win after Ron Perranoski came in to record the save. Back at Los Angeles, it was Don Drysdale’s turn in Game Three. Outdueling Bouton, the tough right-hander overcame a few jams and cries of spitball usage from the Yankees to fire a three-hit, 1-0 shutout.

BTW: Perranoski’s 0.2 innings of relief would be all the Dodgers would need from the bullpen for the entire series.

Being down three games to none seemed bad enough for the Yankees. It was worse. They had to face Koufax again in Game Four.

The sober case of head-shaking continued as one Yankee batter after another came back to the dugout, dejected after being retired yet again by Koufax. No Yankee reached base through the first three innings, and they were shut out through six. Thin hopes remained thanks to Ford, who had allowed only a solo, albeit monstrous, home run to Frank Howard in the fifth.

In the seventh, Mantle came to the rescue and finally dusted off some of Koufax’s immortality, slamming a solo blast of his own to tie the game—but the euphoria would be bitterly short-lived. In the bottom half of the inning, Jim Gilliam hit a high hopper beautifully played by Yankees third baseman Clete Boyer, who fired a strike to Pepitone at first base—except Pepitone lost sight of the ball against a sea of white-shirted, sun-baked Dodgers fans. By the time Pepitone chased the ball down behind him in foul territory, Gilliam was at third. Willie Davis promptly followed up with a sacrifice fly to center, bringing Gilliam home as the go-ahead Dodgers run. Having to play catch-up against Koufax once more, the Yankees were nullified over the final two innings and Los Angeles completed the sweep.

BTW: Only once before, in 1922, had the Yankees been swept in a World Series—but even then, it wasn’t a clean sweep as one game was declared a tie.

Thoroughly silenced by Koufax and Company, the Yankees’ .171 team average and four total runs was the worst offensive showing in World Series play since 1905, when the Philadelphia Athletics could only muster three unearned runs in five games against the New York Giants.

Adding insult to injury, the relatively potent Dodgers hitting was supplied by first baseman—and former Yankee—Bill Skowron, ousted from New York in favor of Pepitone before the season. Skowron made up for a miserable regular season by going 5-for-13 in the Series, including a solo home run in Game Two.

BTW: After hitting at least 20 home runs with 80 RBIs in each of his last three years at New York, Skowron hit just .203 with four homers and 19 RBIs at Los Angeles in 1963.

Any kidding aside, Los Angeles bats were not the big story for this World Series. Showtime was reserved for Sandy Koufax, a quiet, easy-going man who let his pitching arm do all the talking.

Yogi Berra, the veteran Yankees catcher never at a loss for irony—twisted or otherwise—provided one of the more blunt and straightforward opinions of his life when it came to Koufax after the World Series:

“I can see how he won 25 games. What I don’t understand is how he lost five.”

Forward to 1964: The Fizz Kids How the Philadelphia Phillies suffer through baseball’s most infamous pennant race collapse.

Forward to 1964: The Fizz Kids How the Philadelphia Phillies suffer through baseball’s most infamous pennant race collapse.

Back to 1962: Lined to Second Best The New York Yankees’ Ralph Terry barely avoids being labeled a World Series goat for the second time in three years.

Back to 1962: Lined to Second Best The New York Yankees’ Ralph Terry barely avoids being labeled a World Series goat for the second time in three years.

1963 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1963 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

1963 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1963 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

The 1960s: Welcome to My Strike Zone In a decade where baseball as a tradition is turning stale with America’s emerging counter-culturism, major league owners see its biggest problem to be, of all things, an overabundance of offense in the game. The result? An increased strike zone, further contributing to a downward spiral in attendance, but greatly aiding an already talented batch of pitchers.

The 1960s: Welcome to My Strike Zone In a decade where baseball as a tradition is turning stale with America’s emerging counter-culturism, major league owners see its biggest problem to be, of all things, an overabundance of offense in the game. The result? An increased strike zone, further contributing to a downward spiral in attendance, but greatly aiding an already talented batch of pitchers.

Jesse Gonder talks of playing for the glorious New York Yankees, the awful New York Mets and his experiences as a black ballplayer in the majors.

Jesse Gonder talks of playing for the glorious New York Yankees, the awful New York Mets and his experiences as a black ballplayer in the majors.